Chapter 4 What Is the Ideal Surgical Treatment for an Adult Patient with a Lytic Spondylolisthesis?

Lytic spondylolisthesis is a condition where many treatment alternatives have been developed. It can be argued that where several treatment choices are described, then none can be entirely satisfactory; alternatively, all may be satisfactory with little differentiation between them aside from surgeon preference. If the latter is the case, then factors such as operative morbidity and cost should enter into the equation for the ideal treatment. This chapter reviews the current literature in evaluation of these treatment options with a view of identifying the ideal treatment for this condition.

NATURAL HISTORY AND CLASSIFICATION

Lytic spondylolisthesis initially must be defined and classified. The focus of this review is on lytic spondylolisthesis in the adult patient. It should be established, however, that the lytic lesion (defect in the pars interarticularis) develops in childhood. The lesion is not present at birth but has been noted in children as young as 4 months. The pathologic lesion occurs from 5.5 to 7 years of age and during increased activity from ages 11 to 16.1 The prevalence of a lysis is estimated to be 4.4% at age 6 and increases to 6% in adulthood.2 In skeletally immature individuals, the tendency of lumbosacral slip progression is most likely to occur in adolescents younger than 15 years. The majority of skeletally mature individuals with a mild lumbosacral slip are asymptomatic, and slippage after adulthood is uncommon. In a long-term follow-up study, Osterman and colleagues3 note that 90% of the slip had occurred by the time the patient was first seen, and when evaluating long-term outcomes, it was difficult to prove the connection between the radiographic findings and pain.

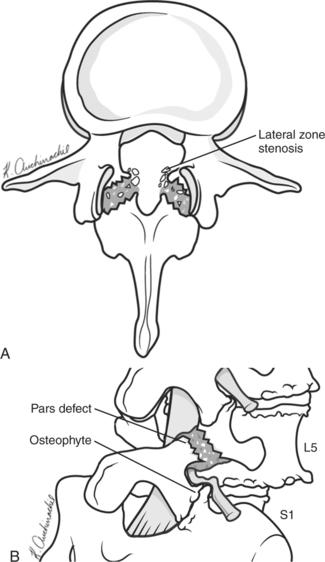

Most adolescents and young adults with spondylolytic spondylolisthesis have no radicular symptoms. When symptoms do occur, it is due to irritation of the exiting nerve root (L5 in a L5-S1 spondylolisthesis). This develops generally after two to three decades and is secondary to disc degeneration with facet arthropathy leading to lateral recess and foraminal stenosis. This compounds the compression of the L5 nerve root caused by the fibrocartilaginous material formed at the edges of the pars defect4–6 (Fig. 4-1).

When comparing treatment options, it is critical that similar pathologic lesions are being compared. Spinal level involved and degree of slip are clinical features that are important in categorization. L5-S1 accounts for 82% of the occurrences of lytic spondylolisthesis; L4-L5 level is involved in 11% of cases. In contrast with the L5-S1 isthmic lesion, the L4-L5 level is more prone to be unstable and subject to further slip progression in adulthood. Sagittal rotation, shear translation, and axial rotation are all greater at the L4-L5 level with a pars defect.7 This can accelerate disc degeneration, further compromise mechanical stability, and lead to greater and earlier onset symptoms compared with the L5-S1 level.3 The L5-S1 level has greater inherent stability, and hence a lower rate of slip progression and symptoms.

HIGH-GRADE SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

High-grade spondylolisthesis is more commonly treated in the adolescent population when the symptoms develop. Few adults are seen with symptomatic severe slips, which were untreated at a younger age. Most studies in adults that include both high- and low-grade spondylolisthesis report no difference in the outcomes; however, the numbers of high-grade slips included are small.8,9

Most authors suggest posterior fusion to include L4 to S1. Numerous approaches to fusion are reported; however, low cohort numbers and no comparative study groups are available for critical evaluation of these various techniques. In summary of the described techniques, these include in situ posterior fusion with instrumentation, transvertebral screws (S1 pedicle screw transgressing the S1 superior end plate to the L5 body), fibular dowels for L5/S1 interbody fusion with L4-S1 instrumentation, titanium cages from either an anterior or posterior approach for interbody L5/S1 fusion, iliac screw supplementation, and L5 vertebrectomy. Good clinical outcomes and fusion rates are described by the advocates of each; however, all studies are class Level IV and V evidence. The role of reduction has inconsistent data to support or refute this, although the risk for neurologic injury is greater with reductions compared with fusions in situ.10

LOW-GRADE SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

Surgery vs. Conservative Management

In a randomized, controlled study comparing operative versus conservative management, fusion with or without instrumentation compared with an exercise program demonstrated superior clinical outcomes at 2 years. At a longer term, 9-year follow-up, some of the shorter term improvement was lost; however, patients with fusion still classified their global outcome as better than patients receiving conservative treatments.11,12

Surgical Techniques

Decompression Alone.

Decompression alone is not typically recommended for spondylolytic spondylolisthesis. Gill13 initially described removal of the L5 lamina and pars fibrocartilage to decompress the L5 nerve roots. This “Gill laminectomy” without fusion is not recommended by most authors because of the concern for destabilization, increased slippage, and worsening of back pain. This sentiment is well established through numerous case series.

One case series has reported good results in a select group of patients using a more limited decompression without fusion. When there is minimal back pain and unilateral L5 symptoms and grade 1 spondylolisthesis are present, Weiner and McCulloch14 describe using a unilateral microsurgical approach to the lateral zone for decompression of the subarticular, foraminal, and extraforaminal structures. As shown in Figure 4-1, the pathoanatomic lesion and compression are lateral. The central portion of the canal is expanded. The fibrocartilaginous mass associated with the pars lesion, facet hypertrophy, and far lateral impingement can all be addressed from this approach.14 These authors do note that, in the majority of cases of spondylolytic spondylolisthesis, fusion is indicated; however, in this subgroup of patients, a role exists for this therapeutic option.

The decision to perform a decompression in addition to fusion should take into account the presence of neurologic symptoms. In a randomized, controlled trial in patients with minimal or no neurologic symptoms, decompression (Gill’s procedure) in addition to posterolateral fusion was compared with a posterolateral fusion alone. The decompression group had a greater rate of pseudarthrosis and unsatisfactory clinical outcomes regardless of the use of instrumentation.15 A wide decompression may exacerbate the instability and impede fusion rate.

Posterolateral Intertransverse Fusion with or without Instrumentation.

Comparing posterolateral intertransverse fusion with and without instrumentation has been evaluated in four randomly controlled trials. In two of these studies, the entire cohort contained patients with a low-grade spondylolytic spondylolisthesis16,17; in the other two studies, spondylolytic spondylolisthesis was a subgroup within the study cohort.18,19 All studies were consistent in their findings in that there were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to functional outcomes and fusion rate.

Interbody Fusion.

The addition of an interbody fusion from either a posterior approach (PLIF), transforaminal approach (TLIF), or anterior approach (ALIF) allows for circumferential stability and a biologically superior environment for fusion. The biologic advantage of a PLIF/ALIF/TLIF over a posterolateral fusion is due to the construct being placed under compression along the weight-bearing axis and near the center of rotation. This allows for a blood supply from the adjacent vertebral bodies to the bone graft within the cage. Madan and Boeree,20 La Rosa and coworkers,21 and Suk and researchers22 have performed retrospective comparative studies comparing posterolateral fusion with instrumentation with or without the addition of PLIF. The correction of subluxation, disc height, and foraminal area were maintained better in the PLIF group. However, this did not result in any clinical or functional advantage over the posterolateral fusion/instrumentation group without PLIF.20 Madan and Boeree21 found that the group with posterolateral fusion/instrumentation had better clinical outcomes than the PLIF group; however, the latter was more predictable in maintaining correction and achieving union.21 Suk and researchers22 found the PLIF condition to have more patients rating their clinical outcome as excellent compared with the posterolateral fusion/instrumentation group.22

A recent study (Level III) describes the use of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion for anterior column support. Lauber and investigators23 prospectively evaluated TLIF in 20 patients who also underwent a Gill laminectomy and posterolateral fusion with instrumentation. They found improvement in Oswestry Disability Index from a mean score of 20 to 11 at 2-year follow-up. The results were maintained at 4 years. This was not a comparative study; however, TLIF was shown to be a viable treatment alternative, and further study with the more established PLIF is needed in comparing anterior column support/fusion techniques.23

Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion.

There is a lack of evidence to support ALIF alone as a treatment alternative. Direct decompression of the nerve roots is not possible with this approach. It is suggested by these authors however (Level IV evidence), that the provision of stability alone may be adequate in managing this pathology.24,25

In a prospective comparative study, Swan and colleagues26 compare posterolateral instrumented fusion/decompression with posterolateral instrumented fusion/decompression with ALIF. Clinical and radiologic outcomes at 2 years were superior in the combined anteroposterior group compared with posterior-alone surgery (Level II evidence). Spruit and coworkers27 and Wang and coauthors28 in two separate case series also describe good clinical outcomes with ALIF in addition to posterolateral fusion, decompression, and instrumentation. Although these latter studies were methodologically poor (Level IV), they report radiologic outcomes with excellent maintenance of slip reduction at 2- to 3-year follow-up. Together, these studies give evidence in support of the use of anterior interbody support (ALIF) in addition to posterior instrumented fusion and decompression.

It is expected that treatment options will continue to evolve as newer implants and minimally invasive techniques continue to develop. A recent trend is toward TLIF whereby interbody fusion with centering of the implant can be achieved from one side. This may have the potential to allow unilateral approaches for the necessary decompression, and provide anterior and posterior column support. Given the current and developing techniques, only through prospective randomized trials will the optimal surgical treatment be established. Table 4-1 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of lytic spondylolisthesis.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Wiltse LL. The etiology of spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1962;44-A:539-560.

2 Fredrickson BE, Baker D, et al. The natural history of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:699-707.

3 Osterman K, Schlenzka D, et al. Isthmic spondylolisthesis in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects, epidemiology, and natural history with special reference to disk abnormality and mode of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 297; 1993; 65-70.

4 Floman Y. Progression of lumbosacral isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. Spine. 2000;25:342-347.

5 Seitsalo S, Osterman K, et al. Progression of spondylolisthesis in children and adolescents. A long-term follow-up of 272 patients. Spine. 1991;16:417-421.

6 Virta L, Osterman K. Radiographic correlations in adult symptomatic spondylolisthesis: A long-term follow-up study. J Spinal Disord. 1994;7:41-48.

7 Grobler LJ, Novotny JE, Wilder DG, et al. L4-5 isthmic spondylolisthesis. A biomechanical analysis comparing stability in L4-5 and L5-S1 isthmic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1994;19:222-227.

8 Hanley E, Levy JA. Surgical treatment of isthmic lumbosacral spondylolisthesis. Analysis of variables influencing results. Spine. 1989;14:48-50.

9 Johnson LP, Nasca RJ, Dunham WK. Surgical treatment of isthmic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1988;13:93-97.

10 Hu S, Bradford DS, Transfeldt E. Reduction of high-grade spondylolisthesis using Edwards instrumentation. Spine. 1996;21:367-371.

11 Ekman PH, Moller H, Hedlund R. The long-term effect of posterolateral fusion in adult isthmic spondylolisthssis: A randomized controlled study. Spine. 2005;5:36-44.

12 Moller H, Hedlund R. Surgery versus conservative management in adult isthmic spondylolisthesis—a prospective randomized study: Part 1. Spine. 2000;25:1711-1715.

13 Gill GG. Long-term follow-up evaluation of a few patients with spondylolisthesis treated by excision of the loose lamina with decompression of the nerve roots without spinal fusion. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 182; 1984; 215-219.

14 Weiner BK, McCulloch JA. Microdecompression without fusion for radiculopathy associated with lytic spondylolisthesis. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:582-585.

15 Carragee EJ. Single-level posterolateral arthrodesis, with or without posterior decompression, for the treatment of isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1175-1180.

16 McGuire RA, Amundson GM. The use of primary internal fixation in spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1993;18:1662-1672.

17 Moller H, Hedlund R. Instrumented and noninstrumented posterolateral fusion in adult spondylolisthesis—a prospective randomized study: Part 2. Spine. 2000;25:1716-1721.

18 France JC, Yaszemski MJ, Lauerman WC, et al. A randomized prospective study of posterolateral lumbar fusion outcomes with and without pedicle screw instrumentsation. Spine. 1999;24:553-560.

19 Thomsen K, Christensen FB, Eiskjaer SP, et al: The effect of pedicle screw instrumentation on functional outcome and fusion rates in posterolateral lumbar spinal fusion: A prospective randomized clinical study. Spine 22:2813–2822.

20 Madan S, Boeree NR. Outcome of posterior lumbar interbody fusion versus posterolateral fusion for spondylolytic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 2002;27:1536-1542.

21 La Rosa G, Conti A, et al. Pedicle screw fixation for isthmic spondylolisthesis: Does posterior lumbar interbody fusion improve outcome over posterolateral fusion? J Neurosurg. 2003;99(2 suppl):143-150.

22 Suk SI, Lee CK, et al. Adding posterior lumbar interbody fusion to pedicle screw fixation and posterolateral fusion after decompression in spondylolytic spondylolisthesis. Spine. 1997;22:210-220.

23 Lauber S, Schulte TL, et al. Clinical and radiologic 2-4-year results of transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in degenerative and isthmic spondylolisthesis grades 1 and 2. Spine. 2006;31:1693-1698.

24 Cheng CL, Fang D, et al. Anterior spinal fusion for spondylolysis and isthmic spondylolisthesis. Long term results in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1989;71:264-267.

25 Ishihara H, Osada R, et al. Minimum 10-year follow-up study of anterior lumbar interbody fusion for isthmic spondylolisthesis. J Spinal Disord. 2001;14:91-99.

26 Swan J, Hurwitz E, Malek F, et al. Surgical treatment for unstable low-grade isthmic spondylolisthesis in adults: A prospective controlled study of posterior instrumented fusion compared with combined anterior-posterior fusion. Spine J. 2006;6:606-614.

27 Spruit M, Van Jonbergen JPW, et al. A concise follow-up of a previous report: Posterior reduction and anterior lumbar interbody fusion in symptomatic low-grade adult isthmic spondylolisthesis. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:828-832.

28 Wang JM, Kim DJ, et al. Posterior pedicular screw instrumentation and anterior interbody fusion in adult lumbar spondylolysis or grade I spondylolisthesis with segmental instability. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:83-88.