Chapter 51 What Is the Best Way to Prevent Heterotopic Ossification after Acetabular Fracture Fixation?

Heterotopic ossification is common after acetabular fracture surgery. Occurring in only approximately 5% of conservatively treated patients,1 it has been reported in as many as 90% of patients after fracture fixation, with severe involvement as high as 50% in some patient groups.2–4 An association with poor results has been reported in many case series.3,4 The specific cause of heterotopic ossification remains obscure, and numerous risk factors have been implicated. The most noted risk factor is stripping of the gluteal muscles from the external surface of the ilium.2–7 Therefore, the use of an extended surgical approach (i.e., extended iliofemoral, triradiate, or modification thereof) in particular is thought to result in a high rate of heterotopic ossification.2,3,5–7 The ilioinguinal approach has been associated with an extremely low rate of ectopic bone formation.3,6

The expressions “severe heterotopic ossification” and “significant heterotopic ossification” are commonly used to describe the amount of heterotopic ossification necessary to impair hip function. However, these terms have actually been defined in differing ways,2,5, 8 possibly causing confusion in the literature. Most reports have used the Brooker classification9 (Table 51-1), which relies solely on the anteroposterior radiographic view of the hip, to grade the severity of heterotopic ossification and have defined Classes III and IV as severe.2,5, 7, 8, 10 Although this system is easy to use, its actual correlation to hip motion and function is questionable.3,5, 11, 12 In fact, a study with Level II evidence has shown that the Brooker classification overestimates the functional importance of “severe heterotopic ossification.”11 Greater than 20% loss of total hip motion has been proposed as the deficit necessary to impair hip function (or the “gold standard”) and heterotopic ossification causing this amount of loss has been defined as “significant.”5,6, 13 In the clinical situation, however, there are many factors other than the presence of heterotopic ossification that can adversely affect hip motion. Therefore, a simple radiographic classification that accurately correlates the presence of heterotopic ossification with this amount of impaired hip motion (absent of any other motion-limiting factors) should be useful in evaluating the independent effect of heterotopic ossification on functional hip motion in patients after acetabular fracture fixation. Level II evidence research has shown that using three radiographs to grade the severity of heterotopic ossification, with the addition of the two standard oblique (Judet) pelvic radiographs, rather than relying only on the anteroposterior view, accomplishes this goal.11 Using this modified Brooker method would be helpful both for individual patient prognosis and general scientific study. Unfortunately, it is the standard Brooker technique that continues in general use. Therefore, the findings from any clinical research investigating heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture fixation, no matter what its apparent “level of evidence” based on study design, may often be diminished by the limitations inherent in the Brooker diagnostic criteria.

TABLE 51-1 Radiographic Grading of Heterotopic Ossification

| GRADE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Class I | Islands of bone within the soft tissues about the hip |

| Class II | Bone spurs from the pelvis or proximal end of the femur, leaving at least 1 cm between opposing bone surfaces |

| Class III | Bone spurs from the pelvis or proximal end of the femur, leaving less than 1 cm between opposing bone surfaces |

| Class IV | Apparent bony ankylosis of the hip |

From Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, Riley LH Jr: Ectopic Ossification following total hip replacement: Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am 55-A:1629–1632, 1973, by permission.

NATURAL HISTORY

In their series of 499 acetabulum fractures operated on without any prophylactic treatment and followed for at least 1 year, Letournel and Judet3 found a 25% (123/499) overall prevalence of heterotopic ossification, using the standard Brooker classification. There were 4% (18/499) with Class I, 10% (50/499) with Class II, 8% (39/499) with Class III, and 3% (16/499) with Class IV ossification. Important distinctions were made among the different surgical approaches, which are thought to be related to differences in the relative extent of the stripping of the gluteal muscles from the external surface of the ilium: the more extensive the stripping, the greater the risk for heterotopic ossification. For the extended iliofemoral approach, there were 4% (1/26) with Class I, 23% (6/26) with Class II, 19% (5/26) with Class III, and 23% (6/26) with Class IV ossification. For the Kocher–Langenbeck approach, there were 4% (11/281) with Class I, 13% (37/281) with class II, 9% (25/281) with Class III, and 2% (6/281) with Class IV ossification. For the ilioinguinal approach, there were 1% (1/138) with Class I, 2% (3/138) with Class II, 1% (2/138) with Class III, and 1% (1/138) with Class IV ossification. Adding stripping of the gluteal muscles from the external surface of the ilium to the standard ilioinguinal approach drastically changed the outcome, resulting in 9% (1/11) with Class I, 9% (1/11) with Class II, 36% (4/11) with Class III, and 0% (0/11) with Class IV ossification. Therefore, the expectation is that without prophylaxis of any kind, “severe heterotopic ossification,” defined as Class III or IV using the standard Brooker technique, will occur in 42% of patients treated through the extended iliofemoral approach, 11% of patients treated through the Kocher–Langenbeck approach, and 2% of patients treated through the ilioinguinal approach.

Matta6 reported on his series of 259 patients with 262 acetabular fractures followed for at least 2 years and operated on without any prophylactic treatment. Moderate (standard Brooker Class II) or severe heterotopic ossification (standard Brooker Class III or IV) that was associated with greater than 20% loss of motion occurred in 9% (23/262) of fractures. This amount of heterotopic ossification was noted in 20% (12/59) of the extended iliofemoral approaches, 8% (9/112) of the Kocher–Langenbeck approaches, and 2% (2/87) of the ilioinguinal approaches.

PREVENTION OPTIONS

In a 1998 survey of 226 members of the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, Morgan and colleagues14 report that prophylaxis for heterotopic ossification was used by 88.3% of the respondents. The stated rationale(s) for this preventative treatment included its effectiveness (39%), perception to be the standard of care (16%), and support in the literature (45%). More than one type of prophylaxis was used by 36.5% of the respondents. Indomethacin was used by 78.6%, low-dose irradiation by 46.5%, low-dose irradiation combined with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) by 15.1%, and NSAIDs other than indomethacin by 3.1%. Therefore, there are three basic preventative treatment options: NSAIDs, low-dose irradiation, and a combination of these two.

EVIDENCE

Indomethacin

The NSAID indomethacin has been shown to decrease the prevalence of heterotopic ossification in experimental animals15–17 and in a number of Level III evidence clinical studies of patients with acetabular fracture.7,8, 10, 18 Most of these clinical studies were retrospective in nature, having the attendant design limitations. More recently, there have been a number of clinical reports with Level I and II evidence, prospectively evaluating the efficacy of indomethacin prophylaxis as compared with a nontreatment control group.19–21 Unfortunately, the data from these studies offer conflicting results. Therefore, critical review of these studies is required, taking into consideration the main important variable of the differing expected baseline prevalence of heterotopic ossification depending on surgical approach, as well as an analysis of the statistical method.

In a Level II study, Iotov21 evaluated the results of prophylaxis with indomethacin in 52 patients operated for fractures of the acetabulum. Twenty-eight received indomethacin prophylaxis, consisting of 25 mg three times per day given orally or per rectum for 30 days after surgery, and 24 composed a control group. The grade of heterotopic ossification was assessed using the Brooker classification. The development of heterotopic ossification was analyzed depending on the type of surgical approach. The rate of severe ossification was 0% in the indomethacin-treated group and 21% in the control group (P < 0.01), mainly after extensile posterior and posterior approaches. One error in this study was including in the control group the one patient who could not tolerate indomethacin because of gastrointestinal symptoms. Ragnarsson and coworkers22 in another level II study had similar findings in a group of 23 patients operated on through the triradiate surgical approach. Of the 14 patients receiving indomethacin prophylaxis (25 mg three times each day for 6 weeks), 10 had no heterotopic ossification, 2 had Brooker Class I, and 2 had Brooker Class II. In the control group, six had Brooker Class II, two had Brooker Class III, and one had Brooker Class IV (P < 0.0001). These Level II findings are consistent with those of the Level III studies.

In contradistinction, Matta and Siebenrock19 report a Level I evidence, randomized, prospective trial indicating that indomethacin was not effective. However, this study was vastly underpowered to detect differences. This study included 107 consecutive patients. Patients with an even hospital number received 100 mg indomethacin by suppository at the end of the operation and then 25 mg by mouth or rectally three times a day for 6 weeks. Those with an odd hospital number received no prophylactic treatment. Patients with all three surgical approaches (extended iliofemoral, Kocher–Langenbeck, and ilioinguinal) were included. The ilioinguinal group (with an expected prevalence of only 2% for heterotopic ossification sufficient to cause impairment, whether by radiographs alone or in combination with measurement of joint motion) represented almost 50% (50/107) of the patients. Thirty-seven patients were in the Kocher–Langenbeck groups, and 20 were in the extended iliofemoral groups. The authors themselves did a power analysis and found low power in their numbers for the motion impairment criteria (24%), and discussed the large patient numbers they would have needed to find significant effects. A simple analysis will show the large sample sizes required in the design of a randomized, prospective study to provide the desired 80% power to minimize the risk for type II error at an alpha < 0.05. Assuming that the comparative change of clinical interest in this study would be a decrease from the expected 2% to 1% for the ilioinguinal approach, 8% to 3% for the Kocher–Langenbeck approach, and 20% to 10% for the extended iliofemoral approach, the sample sizes needed per group for the desired 80% power are approximately 2300, 325, and 200, respectively. The small clinical effect size (2%) and limited drug treatment benefit for the ilioinguinal approach indicates that there is limited value in proceeding with a prospective trial requiring such large patient numbers. In addition, although this was a Level I study, clearly there were not enough patients to answer the study question.

Karunakar and coauthors20 completed a Level I evidence study designed to compare the effect of indomethacin with that of a placebo in reducing the incidence of heterotopic ossification in a prospective, randomized trial. A total of 121 patients with fractures of the acetabulum treated using a Kocher–Langenbeck approach were randomized to receive either indomethacin (once-a-day 75-mg sustainedrelease capsule) or a placebo once daily for 6 weeks. The extent of heterotopic ossification was evaluated on plain radiographs 3 months after operation using the standard Brooker classification. Fifty-nine patients were in the indomethacin group, and 62 were in the placebo group. Significant heterotopic ossification, defined as Brooker Class III to IV, occurred in 9 of 59 patients (15.2%) in the indomethacin group and 12 of 62 (19.4%) receiving the placebo (P = 0.722). On this basis, the authors recommend against the routine use of indomethacin for prophylaxis against heterotopic ossification after isolated fractures of the acetabulum treated using the Kocher–Langenbeck approach. Although this study appears to be well designed, it suffers from important deficiencies. Eighteen patients randomized to the indomethacin group did not complete their course of prophylactic therapy. These patients were maintained in the indomethacin treatment group for the statistical analysis, which on the surface seems a confounding variable. This approach is consistent with the “intent-to-treat” analysis design. However, what is also required, which was not provided by the authors, is a secondary analysis of these noncompliant patients. This secondary analysis is explanatory in nature, comparing compliant with noncompliant patients within the treatment group. This analysis is critical because it may change the overall findings by revealing a significant difference in compliant versus noncompliant patients. The sample size required to provide the desired 80% power to minimize the risk for type II error at an alpha < 0.05 is 80 per group for the Kocher–Langenbeck approach. This calculation assumes that 11% is the expected baseline prevalence with the Brooker classification and uses an 11% decrease to 0% (the maximum possible) to define the comparative change of clinical interest. With the standard drug study expectation of a 5% comparative change of clinical interest from 11% to 6%, 490 per group would be required. Ninety patients per group would be required to show a 10% treatment difference. The authors recognized the fact that their study was underpowered. However, they explained away the need to adequately power the study by stating that the clinical effect size is small. If that is truly the case, if the impairment from heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture fixation through the Kocher–Langenbeck approach is minimal without any preventative treatment, then there was no point in doing this study based on the known natural history. In summary, the authors did not add the minimally required 20 to 30 patients per group or do the secondary analysis, and left the study question unanswered.

A consistent finding is that a certain number of patients will discontinue their prescribed course of indomethacin treatment.20,21 Patients discontinue the drug either because of medication-related gastrointestinal symptoms or just failure to “follow the doctor’s orders.”

Other Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Experimental evidence exists to suggest that NSAIDs (including selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors) other than indomethacin have effects similar to indomethacin in the prevention of heterotopic ossification.23–25 However, there are limited clinical studies in patients with total joint arthroplasty24,26, 27 and essentially none for patients with acetabular fracture. Because all NSAIDs potentially have the same effects as indomethacin, uncontrolled use of NSAIDs other than indomethacin by study patients represents an important confounding variable investigators have not routinely addressed.

Low-Dose Irradiation

Some Level III evidence supports using low-dose irradiation to prevent heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture fixation.2,28, 29 In a retrospective study of 37 patients treated with an extended or modified extended surgical approach, Bosse and colleagues2 used prophylactic radiation, delivering 1000 cGy in 200-cGy increments, starting on the third postoperative day. They found a significant (P < 0.01) difference in severe (Brooker class III or IV) heterotopic ossification between the no-treatment control group and the irradiation group. In 1996, Anglen and Moore28 showed similar findings in patients treated with 800 cGy as a single dose within 3 days of surgery. Childs and coworkers29 found a 700-cGy single-dose regimen to be effective.

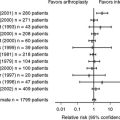

From our review of the English-language literature, no Level I or II evidence studies compare low-dose radiation therapy with a no-treatment control group for patients after acetabular fracture fixation. However, such evidence does exist comparing irradiation with indomethacin.30,31 Moore, Goss, and Anglen30 compared indomethacin (25 mg, given three times daily for 6 weeks) with irradiation with 800 cGy delivered within 3 days of operation.30 Plain radiographs were evaluated using Brooker classification. The investigators found no difference between the two treatment methods. Once again, this study was grossly underpowered. The authors recognized this issue, stating that “for this approximate sample size and outcome effect, p = 0.05 with a power of 80% would require an outcome difference of 27% between the two groups.”30 In a follow-up to this study, Burd, Lowry, and Anglen31 performed a comparable study in a larger group of patients with Level II evidence. Their findings were similar.31 Although there are some issues with how the statistical data were presented, the methods appear adequate to support their findings of no difference between the indomethacin and irradiation treatment groups. These authors used the intent-to-treat method. Therefore, 16 patients who were randomized into either the indomethacin (8 patients) or irradiation (8 patients) treatment groups, but did not receive these treatments, were included. As has been discussed previously, these authors appropriately included a secondary analysis of the 16 patients who did not receive treatment. Interestingly, all 16 had heterotopic ossification, which was Class III or IV in 6 of them. In summary, based on the available evidence, it appears that low-dose irradiation does decrease the prevalence of heterotopic ossification in patients with acetabular fracture.

Combination Indomethacin and Low-Dose Irradiation

A theoretical basis exists for the use of combination therapy. Experimental evidence indicates that radiation therapy and indomethacin decrease heterotopic ossification by different pathways.32 However, to the best of our knowledge, there is only Level IV evidence in support of using the combination of indomethacin and low-dose irradiation to prevent heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture fixation.33 In this series that Moed and Letournel reported,33 the use of this regimen essentially eliminated postoperative heterotopic ossification and there was no progression, even when early ossification was seen on preoperative radiographs. Childs and coworkers,29 in an uncontrolled Level III portion of their study, were unable to show a significant difference between the 700-cGy single-dose regimen and the combination of indomethacin and low-dose irradiation.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Timing and Dosing of Preventative Therapies

The standard prescription for indomethacin for acetabular fracture patients is 75 mg/day delivered either orally or per rectum as 25 mg in three divided doses (TID), instituted within 24 hours of surgery and continued for 6 weeks after surgery. In a Level II study, Iotov21 used the medication for only 30 days with success. Evidence exists from other patient populations (notably, patients with total joint arthroplasty) that shorter treatment regimens can be used. However, no data support this decrease for patients with acetabular fracture. Karunakar and coauthors,20 in their Level I study detailed earlier, used once-a-day 75-mg sustained-release capsules without success in preventing heterotopic ossification. Interestingly, this study was one of the few not to show a significant effect with indomethacin usage. Whether this dosing method affected the outcome is not known. The “effective preventative dose” of indomethacin is not known. Missing one or two of the three prescribed 25-mg doses in the TID regimen may not cause the loss of clinical effectiveness, as opposed to failing to take an entire day’s medication by missing the single once-a-day 75-mg sustained-release capsule.

Currently, low-dose radiation therapy usually consists of 700 cGY delivered to the hip region as a single dose within 72 hours after surgery. Evidence in support of the various dosing regimens for patients with acetabular fracture is limited. Most of the reported Level I to III evidence studies in patients with acetabular fracture presented data based on using either 1000 cGy in increments over a number of days or 800 cGy as a single dose within 3 days of surgery. Childs and coworkers,29 in a study with Level II evidence, evaluated the timing of postoperative irradiation using a 700-cGy single-dose regimen. They note no increase in heterotopic ossification with up to a 72-hour interval between surgery and radiation therapy.

Complications

Experimental animal studies have also shown that indomethacin will decrease the formation of new bone,34,35 impair fracture healing,36,37 and inhibit the remodeling of haversian bone.38 In the rabbit, indomethacin decreased the torsional strength of healing bone.39 In an in vitro study, NSAIDs have been shown to adversely affect human osteoblasts.40 However, this effect on the osteoblasts is reversible after discontinuation of the drug.40 Clinical correlation had been scarce,34 and no problems with fracture healing had been noted in many reported Level III evidence series of patients with acetabular fracture.7,8, 10 However, a more recent Level II study in patients with acetabular fracture has shown that the use of indomethacin increases the risk for long-bone nonunion.41 This potential complication is likely associated with all NSAID use.40,42 As noted earlier, a certain number of patients will discontinue their prescribed course of indomethacin treatment either because of medication-related gastrointestinal symptoms or just failure to “follow the doctor’s orders.”10,20, 21, 31 Several important risk factors predisposing patients to NSAIDinduced gastrointestinal symptoms have been identified, including age, prednisone use, underlying severe illness, and a history of NSAID-induced gastrointestinal symptoms.43 Length of therapy is also thought to be a factor with patients receiving short-term therapy (less than 1 month) at less risk.44 Level I evidence suggests that the synthetic prostaglandin E1 analog, misoprostol, is preventative for NSAID-induced gastric and duodenal mucosal lesions and symptoms but does not interfere with the antirheumatic activity of the administered NSAID.43,45 However, its use, or that of any other gastroduodenal mucosal protective agent, in patients with acetabular fracture receiving indomethacin for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis has not been studied.

The possibility of induced malignant disease is the main concern with low-dose radiation therapy, although genetic alterations in offspring may also be at issue. Radiation-induced malignancy is rare, and no case of malignancy caused by low-dose irradiation for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis has been reported.46,47 However, pelvic low-dose irradiation with limited fields in the range of 260 to 530 cGy has been given for metropathia haemorrhagica.48 Mortality was greater more than 30 years after radiotherapy than between 5 and 29 years after radiotherapy in this Level III epidemiologic study, suggesting that full risks for development of cancer may not be assessed for more than 30 years. Low-dose irradiation for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis has not been used that long, and unfortunately, study has shown that patients with acetabular fracture often fail to return for even short-term follow-up.47 In one study of 25 patients with acetabular fracture fixation treated with low-dose irradiation for heterotopic ossification prophylaxis, not a single patient returned for follow-up beyond 5 years.47

Cost

A substantial cost difference exists between indomethacin and low-dose irradiation prophylaxis. Burd and colleagues,31 in 2001, reported a radiation therapy cost of $2400 compared with $12 for a 6-week course of indomethacin at their institution. However, the costs will vary from institution to institution. In addition, costs for possible complication-related treatments have yet to be considered in the equation.

Given the baseline prevalence of heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture fixation without the use of prophylactic treatment reported by Letournel and Judet3 and Matta,6 one may reasonably conclude that prophylaxis is not necessary for some patient groups. Patients treated using the ilioinguinal approach fit in this category. Patients treated using more extensive surgical approaches involving stripping of the gluteal muscles from the external surface of the ilium (i.e., extended iliofemoral, triradiate, or modification thereof) present the opposite end of the spectrum. Patients undergoing acetabular fracture fixation through the Kocher–Langenbeck approach present an intermediate risk. In view of the levels of evidence gleaned from our review of the literature, patients with acetabular fracture treated using these approaches involving stripping of the gluteal muscles from the external surface of the ilium are candidates for preventative treatment (Table 51-2). The potential adverse effects of preventative treatments must be considered. Therefore, the question remains, which patients are at sufficient risk for acquiring an amount of heterotopic ossification necessary to impair hip function?

| RECOMMENDATIONS | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECIMMENDATION |

|---|---|

HO, heterotopic Ossification; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

We recommend preventative treatment for heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture fixation using the extended iliofemoral surgical approach or similar extensive surgical approaches (see Table 51-2). However, care should be taken regarding patient selection and method of prophylaxis.

We recommend preventative treatment with indomethacin for heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture fixation through the Kocher–Langenbeck surgical approach or similar posterolateral surgical approaches. Despite the fact that there is conflicting evidence regarding this treatment (see Table 51-2), we believe that with careful patient selection, the potential benefit outweighs the overall risk. However, this is not the case for low-dose irradiation and we do not recommend its use.

1 Pennal GF, Davidson J, Garside H, et al. Results of treatment of acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop. 1980;151:115-123.

2 Bosse MJ, Reinert CM, Ellwanger F, et al. Heterotopic ossification as a complication of acetabular fractures: Prophylaxis with low-dose irradiation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70-A:1231-1237.

3 Letournel E, Judet R. Fractures of the Acetabulum, 2nd ed., New York: Springer Verlag; 1993:541-563.

4 Mears DC, Rubash HE. Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures. Thorofare, NJ: Slack, 1986;411-414.

5 Ghalambor N, Matta J, Bernstein L. Heterotopic ossification following operative treatment of acetabular fracture: An analysis of risk factors. Clin Orthop. 1994;305:96-105.

6 Matta JM. Fractures of the acetabulum: Accuracy of reduction and clinical results in patients managed operatively within three weeks after injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78-A:1632-1645.

7 Moed BR, Maxey JW. The effect of indomethacin on heterotopic ossification following acetabular fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma. 1993;7:33-38.

8 Moed BR, Karges DE. Prophylactic indomethacin for the prevention of heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture surgery in high-risk patients. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8:34-39.

9 Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, Riley LHJr. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement: Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55-A:1629-1632.

10 McLaren AC. Prophylaxis with indomethacin for heterotopic bone after open reduction of fractures of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72-A:245-247.

11 Moed BR, Smith ST. Three-view radiographic assessment of heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture surgery: Correlation with hip motion in 100 cases. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:93-98.

12 Alonso J, Davila R, Bradley E. Extended iliofemoral versus triradiate approaches in management of associated acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop. 1994;305:81-87.

13 Matta JM, Mehne DK, Roffi R. Fractures of the acetabulum: Early results of a prospective study. Clin Orthop. 1986;205:241-250.

14 Morgan SJ, Jeray KJ, Phieffer LS, et al. Attitudes of orthopaedic trauma surgeons regarding current controversies in the management of pelvic and acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:526-532.

15 Moed BR, Resnick RB, Fakhouri AJ, et al. Effect of two nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on heterotopic bone formation in a rabbit model. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9:81-87.

16 Nilsson OS, Bauer HCF, Brosjo O, Tomkvist H. Influence of indomethacin on induced heterotopic bone formation in rats: Importance of length of treatment and of age. Clin Orthop. 1986;207:239-245.

17 Tornkvist H, Bauer FCH, Nilsson OS. Influence of indomethacin on experimental bone metabolism in rats. Clin Orthop. 1985;193:264-270.

18 Johnson EE, Kay RM, Dorey FJ. Heterotopic ossification prophylaxis following operative treatment of acetabular fracture. Clin Orthop.; 305; 1994; 88-95.

19 Matta JM, Siebenrock KA. Does indomethacin reduce heterotopic bone formation after operations for acetabular fractures? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79-B:959-963.

20 Karunakar MA, Sen A, Bosse MJ, et al. Indometacin as prophylaxis for heterotopic ossification after the operative treatment of fractures of the acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg. 2006;88:1613-1617.

21 Iotov A. Heterotopic ossification in surgically treated patients with acetabular fractures and indomethacin prophylaxis for its prevention. Ortopediya i Travmatologiya. 2000;36:367-373.

22 Ragnarsson B, Danckwardt-Lilliestrom G, Mjoberg B. The triradiate incision for acetabular fractures: A prospective study of 23 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:515-519.

23 Tornkvist H, Nilsson OS, Bauer FCH, Lindholm TS. Experimentally induced heterotopic ossification in rats influenced by anti-inflammatory drugs. Scand J Rheumatol. 1983;12:177-180.

24 Elmstedt E, Lindholm TS, Nilsson OS, Tornkvist H. Effect of ibuprofen on heterotopic ossification after hip replacement. Acta Orthop Scand. 1985;56:25-27.

25 Banovac K, Williams JM, Patrick LD, Levi A. Prevention of heterotopic ossification after spinal cord injury with COX-2 selective inhibitor (rofecoxib). Spinal Cord. 2004;42:707-710.

26 Grohs JG, Schmidt M, Wanivenhaus A. Selective COX-2 inhibitor versus indomethacin for the prevention of heterotopic ossification after hip replacement: A double-blind randomized trial of 100 patients with 1-year follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2007;78:95-98.

27 Vielpeau C, Joubert JM, Hulet C. Naproxen in the prevention of heterotopic ossification after total hip replacement. Clin Orthop. 1999:279-288.

28 Anglen JO, Moore KD. Prevention of heterotopic bone formation after acetabular fracture fixation by single-dose radiation therapy: A preliminary report. J Orthop Trauma. 1996;10:258-263.

29 Childs HA3rd, Cole T, Falkenberg E, et al. A prospective evaluation of the timing of postoperative radiotherapy for preventing heterotopic ossification following traumatic acetabular fractures. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47:1347-1352.

30 Moore KD, Goss K, Anglen JO. Indomethacin versus radiation therapy for prophylaxis against heterotopic ossification in acetabular fractures: A randomised, prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80-B:259-263.

31 Burd TA, Lowry KJ, Anglen JO. Indomethacin compared with localized irradiation for the prevention of heterotopic ossification following surgical treatment of acetabular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:1783-1788. [erratum appears in J Bone Joint Surg 84-A:100, 2002].

32 Ahrengart L, Lindgren U, Reinholt FP. Comparative study of the effects of radiation, indomethacin, prednisolone, and ethane-l-hydroxy-l,l-diphosphonate (EHDP) in the prevention of ectopic bone formation. Clin Orthop. 1988;229:265-273.

33 Moed BR, Letournel E. Low-dose irradiation and indomethacin prevent heterotopic ossification after acetabular fracture surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76-B:895-900.

34 Sudmann E, Hagen T. Indomethacin-induced delayed fracture healing. Arch Orthop Unfalichir. 1976;85:151-154.

35 Tornkvist H, Bauer FCH, Nilsson OS. Influence of indomethacin on experimental bone metabolism in rats. Clin Orthop. 1985;193:264-270.

36 Allen HL, Wase A, Bear WT. Indomethacin and aspirin: Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents on the rate of fracture repair in the rat. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51:595-600.

37 Bo J, Sudmann E, Marton PF. Effect of indomethacin on fracture healing in rats. Acta Orthop Scand. 1976;47:588-599.

38 Sudmann E, Bang G. Indomethacin-induced inhibition of Haversian remodelling in rabbits. Acta Orthop Scand. 1979;50:621-627.

39 Tornkvist H, Lindholm TS, Netz P, et al. Effect of ibuprofen and indomethacin on bone metabolism reflected in bone strength. Clin Orthop. 1984;187:255-259.

40 Evans CE, Butcher C. The influence on human osteoblasts in vitro of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs which act on different enzymes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86-B:444-449.

41 Burd TA, Hughes MS, Anglen JO. Heterotopic ossification prophylaxis with indomethacin increases the risk of long-bone nonunion. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85-B:700-705.

42 Giannoudis PV, MacDonald DA, Matthews SJ, et al. Nonunion of the femoral diaphysis: The influence of reaming and Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82-B:655-658.

43 Graham DY, White RH, Moreland LW, et al. Duodenal and gastric ulcer prevention with misoprostol in arthritis patients taking NSAIDs. Misoprostol study group. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:257-262.

44 Wilson DE, Galati JS. NSAID gastropathy: Prevention and treatment. J Musculoskel Med. 1991;8:55-70.

45 Saggioro A, Alvisi A, Blasi A, et al. Misoprostol prevents NSAID-induced gastroduodenal lesions in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1991;23:119-123.

46 Lo TCM. Radiation therapy for heterotopic ossification. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1999;9:163-170.

47 Cornes PGS, Shahidi M, Glees JP. Heterotopic bone formation: Irradiation of high risk patients. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:448-452.

48 Darby SC, Reeves G, Key T, et al. Mortality in a cohort of women given X-ray therapy for metropathia haemorrhagica. Int J Cancer. 1994;56:793-801.