Chapter 78 What Is the Best Treatment for Recurrent Ankle Instability?

Incidence of Recurrent Ankle Instability

Most acute injuries are treated by a rehabilitation program. The remaining 15% to 20% who remain symptomatic may require surgical intervention.1 In the United Kingdom, 302,000 sprains are treated per year.2 Recurrent sprains may result in more lost days of sport than the initial injury.3

Anatomy of the Lateral Collateral Ligaments

The lateral collateral ligaments stabilize the ankle joint to episodes of inversion sprains. The anterior talofibular ligament runs from the anterior aspect of the fibula to the neck of the talus laterally at its junction to the body of the talus.4 The calcaneofibular ligament starts just inferior and posterior to the origin of the talofibular ligament, and inserts into the lateral border of the calcaneus running posteriorly.5 The talofibular ligament therefore stabilizes the ankle by preventing the talus from subluxing anteriorly in the ankle mortise, whereas the calcaneofibular ligament prevents inversion of both the talus and calcaneus at the ankle joint and subtalar joint, respectively.

Pathoanatomy

The anatomy of the hindfoot has a critical effect on the loading of the lateral ligament complex. A cavus foot position may cause medial displacement of the joint reaction force in the ankle, increasing strain on the lateral collateral ligaments.6 Posterior displacement of the tip of the fibula has been hypothesized as being the cause of recurrent instability. These anatomic variations may, however, represent part of a constellation of cavus foot deformity.7 Symptomatic chronic instability may be caused by the combination of foot shape and an acute injury. A study of patients with ankle instability awaiting surgery compared with normal control subjects showed that those with instability had a more varus heel.6

TREATMENT OF THE ACUTE INJURY

The general consensus of the literature is that the results of early surgical repair do not result in better outcomes than nonoperative treatment.8–11 Two Cochrane database reviews showed insufficient evidence to recommend surgical intervention. The most recent is based on the review of 20 articles. A trend existed toward worse outcome in the surgical group for longer recovery times, stiffness, and surgical complications {Kerkhoffs, 2007 #585} (grade B). Repair and reconstruction is therefore recommended only for patients with chronic symptoms of ankle instability.

Limitations of Outcomes Studies

In the Cochrane database review, no evidence was found to support acute lateral ligament reconstruction compared with conservative treatment. However, the studies analyzed were not designed well enough to definitively answer the question.9 The obvious limitations of articles on recurrent lateral ankle instability include retrospective design with nonvalidated outcome scores without control groups. Less obvious may be the presence or absence of copathologies with ankle instability. Hintermann and colleagues12 report on 148 patients with medial or lateral instability. Cartilage injury was found in 66% of patients with lateral instability, and 98% of patients with medial instability. Another study showed a 98% rate of intra-articular pathology is associated with lateral ankle instability. The author notes the most common finding was synovitis with a 25% rate of chondral injuries in the ankle.13 Other authors have documented similar findings.13–15 Injury to the peroneal tendons and tendonitis are associated with recurrent lateral ankle instability16,17 with 25% of patients having a peroneal tendon injury.

In summary, older studies do not address the copathologies, nor do they discuss or outline their concomitant treatment protocol on finding these associated issues. For this reason alone, the outcomes for ankle ligament stabilization may be improved in recent articles with the advent of routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ankle arthroscopy, and treatment of osteochondral defects. Based on the Level IV studies, a grade I recommendation exists for the routine use of advanced diagnostic testing, such as MRI. The diagnostic role of routine arthroscopic debridement at the time of lateral ligament reconstruction has not been determined; however, its use is now recommended by some authors15,18 (grade I). More studies are required in regard to this specific issue.

Nonoperative Treatment of Recurrent Ankle Instability

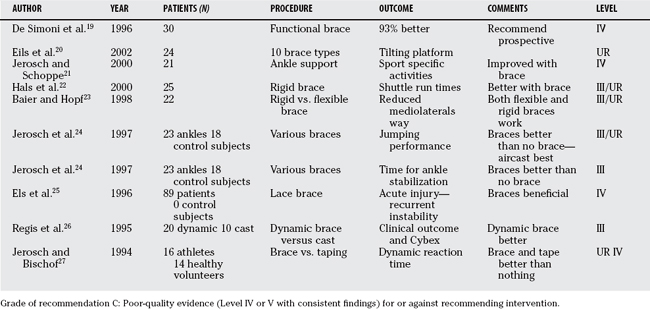

Brace Treatment.

The obvious study, comparison of brace versus no brace treatment on the midterm outcome of ankle instability or symptoms reported by the patient, has not been done. The articles written on bracing for chronic instability are summarized in Table 78-1. Future research should ideally be prospective, randomized, and based on patient-reported outcomes.

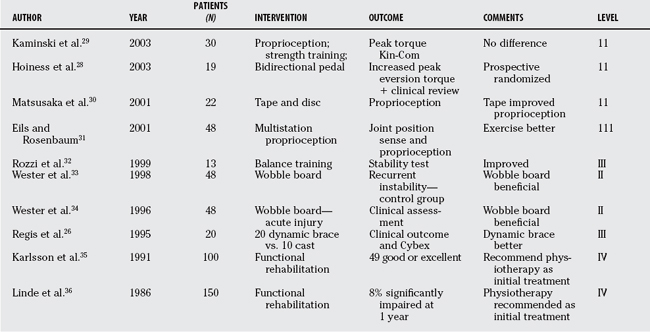

Physiotherapy.

Three studies of Level II quality exist supporting the use of physiotherapy for recurrent instability. Four studies are Level II and IV quality, and three cannot be rated because they report outcomes that were not clinical and focused on indirect evidence such as peroneal reaction times. Based on these studies, a grade B recommendation exists for treatment of ankle instability with physiotherapy. One study used an unusual treatment regimen28 that is an unconventional form of physiotherapy—a bidirectional bicycle pedal that is not available to most patients (Table 78-2).

Surgical Treatment of Recurrent Ankle Instability

Alternatively, the ligaments can be reconstructed. The reconstruction can be either anatomic or nonanatomic. Nonanatomic reconstructions include the Evans procedure (rerouting of the peroneus brevis through the fibula) or the Watson–Jones procedure (peroneal tendon weave). These reconstructions as a result sacrifice the active evertors of the ankle for a static restraint. Because the reconstruction is nonanatomic, joint motion may be restricted, so that the Evans procedure, for example, restricts subtalar joint motion.37,38 In one retrospective case–control study with long-term follow-up, the rate of arthritis, ongoing instability, and reoperation rate all favored anatomic repair over Evans tenodesis.39 Nine studies recommend against the use of nonanatomic reconstructions.39–47 Another study showed impaired kinematics after Evans tenodesis and recommended against its use.42 In a review of patients undergoing the Broström procedure compared with the Christman–Snook nonanatomic reconstruction, patients with the reconstruction complained of the ankle feeling “too tight.”48 Current opinion supports the use of an anatomic reconstruction or repair without sacrifice of the active evertors of the ankle.

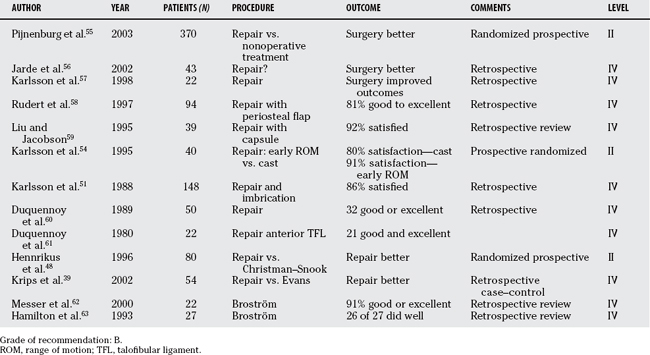

Anatomic Repair.

Anatomic repair (Broström repair, with or without modifications) remains one of the mainstays of surgical treatment of recurrent ankle instability.49 Broström50 described the imbrication of the lateral collateral ligaments. Karlsson and coworkers51 modified the Broström repair by bringing the distal segments of the ligaments through drill holes and oversewing the repair to reinforce it. Gould and investigators52 modified the Broström repair by oversewing the extensor retinaculum over the top of the repaired ligaments. I prefer to use both the Karlsson and Gould modifications.53 Three studies are prospective, although one study compares two postoperative regimens for one type of reconstruction.54 The strongest study was performed by Pijnenburg and researchers,55 a Level I, randomized, prospective study. The remainder of the studies is Level IV quality. Overall, the grade of re-commendation is B for anatomic repair of the lateral ligaments for recurrent instability. All of the studies support the anatomic reconstruction, as opposed to the significant number of studies failing to support nonanatomic reconstruction. Notably, the majority of ideal studies have been done within the anatomic repair group, with consistent results. The anatomic repair should therefore be considered the standard of care for surgical intervention of recurrent lateral ankle instability, based on the level of evidence with the current studies and outcomes available (Table 78-3).

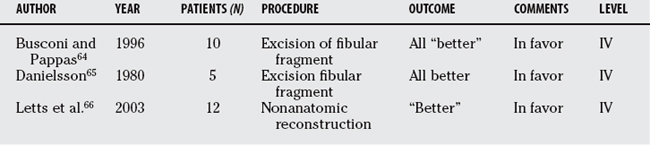

Instability in Children.

Children and teenagers have weaker bones than adults; as a result, they are at risk for avulsing the tip of the fibula with an inversion sprain. In this case, the unstable ankle joint is associated with a fracture, providing a different pathology and a different reconstruction. The outcome of removal of the bone fragment and repair of the ligament to bone has been studied previously. The outcome studies on this procedure are summarized later in this chapter. As a subgroup of patients with ankle instabilities, they represent a small percentage of all patients with ankle instability. Notably, few patients have been studied in retrospective reviews, but all reporting good outcomes. Therefore, with a limited number of patients studied, a level C grade of recommendation exists for this procedure in children with ankle instability (see Table 78-4).

Nonanatomic Reconstruction.

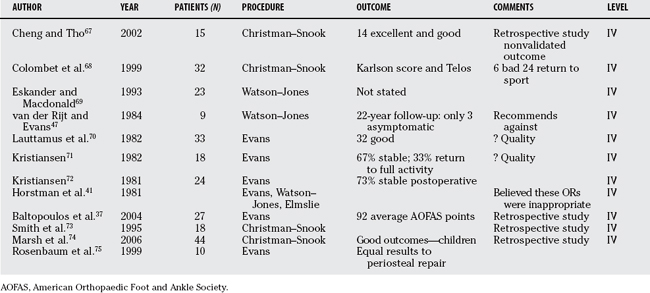

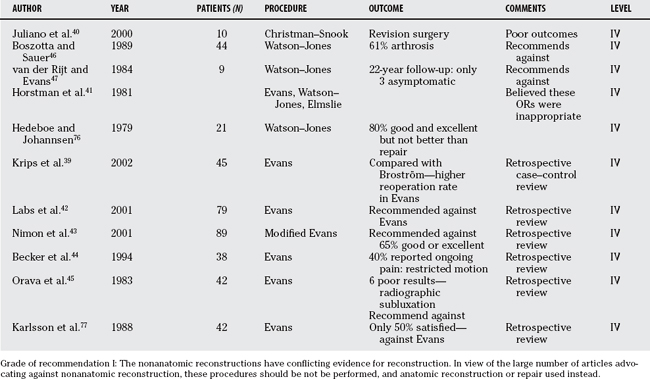

Grade of recommendation I exists for the nonanatomic reconstructions in view of the conflicting evidence for reconstruction. A large number of articles advocate against nonanatomic reconstruction and that these procedures should not be performed, and anatomic reconstruction or repair used instead. The articles on poor outcomes of nonanatomic reconstructions support the abandonment of the procedure (Table 78-5 and 78-6).

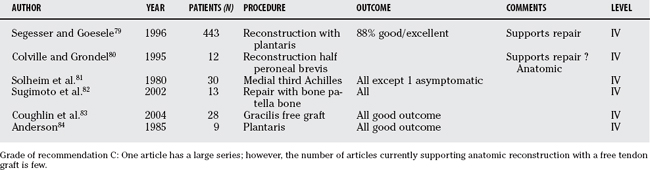

Anatomic Reconstruction with Use of Allograft or Autograft Tendon Augmentation.

Segesser79 and Anderson84 have used the plantaris tendon to reconstruct the lateral collateral ligaments. A drill hole is made through the calcaneus to deliver the tendon at the insertion of the calcaneofibular ligament. The tendon is then brought up through drill holes in the fibula and back onto the insertion of the anterior talofibular ligament, repairing to the talus with drill holes. Colville80 repaired the lateral ligaments using half of peroneus brevis, thus preserving the function of the brevis muscle as an evertor. Coughlin83 uses a free gracilis graft through drill holes. A modification of the Anderson technique using a free gracilis autograft is our preferred technique for lateral ligament reconstruction. No outcome review has been performed to date.78

All articles to date support the concept of an anatomic reconstruction. Some surgeons select the anatomic reconstruction for patients with more attenuated tissue. Because these tendon autograft or allograft lateral ligament reconstruction are newer techniques, limited outcome data are available. However, all articles support of anatomic reconstruction with a grade C recommendation (see Table 78-7).

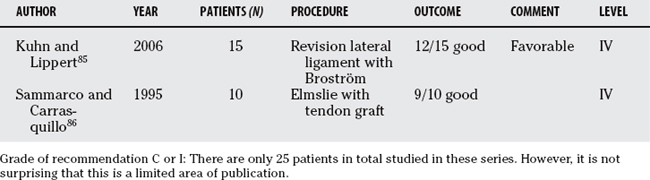

Revision Lateral Ligament Reconstruction.

Only two articles identified the outcome of lateral ligament reconstruction for revision of a previous failed repair. As would be expected, few articles have been published in this area. Those two articles support the principle with a grade C recommendation, with the caution that few patients have been studied. Table 78-9 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of recurrent ankle instability.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Baumhauer JF, O’Brien T. Surgical considerations in the treatment of ankle instability. J Athl Train. 2002;37:458-462.

2 Van Bergeyk AB, Younger A, Carson B. CT analysis of hindfoot alignment in chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:37-42.

3 Berkowitz MJ, Kim DH. Fibular position in relation to lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:318-321.

4 Ferran NA, Maffulli N. Epidemiology of sprains of the lateral ankle ligament complex. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:659-662.

5 Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, et al. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union: Part 2 training injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:767-775.

6 Colville MR. Surgical treatment of the unstable ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:368-377.

7 Burks RT, Morgan J. Anatomy of the lateral ankle ligaments. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:72-77.

8 Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Sward L. Early functional treatment for acute ligament injuries of the ankle joint. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1996;6:341-345.

9 Kerkhoffs GM, Handoll HH, de Bie R, et al. Surgical versus conservative treatment for acute injuries of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.; 3; 2002; CD000380.

10 Kerkhoffs GM, Rowe BH, Assendelft WJ, et al. Immobilisation for acute ankle sprain. A systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121:462-471.

11 Karlsson J, Lansinger O. Lateral instability of the ankle joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 276; 1992; 253-261.

12 Hintermann B, Boss A, Schafer D. Arthroscopic findings in patients with chronic ankle instability. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:402-409.

13 Komenda GA, Ferkel RD. Arthroscopic findings associated with the unstable ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:708-713.

14 Taga I, Shino K, Inoue M, et al. Articular cartilage lesions in ankles with lateral ligament injury. An arthroscopic study. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:120-127.

15 Ferkel RD, Chams RN. Chronic lateral instability: Arthroscopic findings and long-term results. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:24-31.

16 Takao M, Komatsu F, Naito K, et al. Reconstruction of lateral ligament with arthroscopic drilling for treatment of early-stage osteoarthritis in unstable ankles. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1119-1125.

17 DIGiovanni BF, Fraga CJ, Cohen BE, Shereff MJ. Associated injuries found in chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:809-815.

18 Bonnin M, Tavernier T, Bouysset M. Split lesions of the peroneus brevis tendon in chronic ankle laxity. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:699-703.

19 De Simoni C, Wetz HH, Zanetti M, et al. Clinical examination and magnetic resonance imaging in the assessment of ankle sprains treated with an orthosis. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:177-182.

20 Eils E, Demming C, Kollmeier G, et al. Comprehensive testing of 10 different ankle braces. Evaluation of passive and rapidly induced stability in subjects with chronic ankle instability. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2002;17:526-535.

21 Jerosch J, Schoppe R. Midterm effects of ankle joint supports on sensomotor and sport-specific capabilities. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:252-259.

22 Hals TM, Sitler MR, Mattacola CG. Effect of a semi-rigid ankle stabilizer on performance in persons with functional ankle instability. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:552-556.

23 Baier M, Hopf T. Ankle orthoses effect on single-limb standing balance in athletes with functional ankle instability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:939-944.

24 Jerosch J, Thorwesten L, Frebel T, et al. Influence of external stabilizing devices of the ankle on sport-specific capabilities. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1997;5:50-57.

25 Els M, Niggli A, Ochsner PE. [Functional therapy using a laced ankle brace in supination trauma of the ankle joint with lesions of the capsule-ligament apparatus]. Swiss Surg. 1996;2:280-283.

26 Regis D, Montanari M, Magnan B, et al. Dynamic orthopaedic brace in the treatment of ankle sprains. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:422-426.

27 Jerosch J, Bischof M. [The effect of proprioception on functional stability of the upper ankle joint with special reference to stabilizing aids]. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 1994;8:111-121.

28 Hoiness P, Glott T, Ingjer F. High-intensity training with a bi-directional bicycle pedal improves performance in mechanically unstable ankles—a prospective randomized study of 19 subjects. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2003;13:266-271.

29 Kaminski TW, Buckley BD, Powers ME, et al. Effect of strength and proprioception training on eversion to inversion strength ratios in subjects with unilateral functional ankle instability. Br J Sports Med. 2003;37:410-415.

30 Matsusaka N, Yokoyama S, Tsurusaki T, et al. Effect of ankle disk training combined with tactile stimulation to the leg and foot on functional instability of the ankle. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:25-30.

31 Eils E, Rosenbaum D. A multi-station proprioceptive exercise program in patients with ankle instability. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:1991-1998.

32 Rozzi SL, Lephart SM, Sterner R, et al. Balance training for persons with functionally unstable ankles. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:478-486.

33 Wester JU, Jespersen SM, Nielsen KD, et al. [Training on a wobble board following lateral ankle joint sprains]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1998;160:632-634.

34 Wester JU, Jespersen SM, Nielsen KD, et al. Wobble board training after partial sprains of the lateral ligaments of the ankle: A prospective randomized study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;23:332-336.

35 Karlsson J, Lansinger O, Faxen E. [Lateral instability of the ankle joint (2). Active training programs can prevent surgery]. Lakartidningen. 1991;88:1404-1407.

36 Linde F, Hvass I, Jurgensen U, et al. Early mobilizing treatment in lateral ankle sprains. Course and risk factors for chronic painful or function-limiting ankle. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1986;18:17-21.

37 Baltopoulos P, Tzagarakis GP, Kaseta MA. Midterm results of a modified evans repair for chronic lateral ankle instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 422; 2004; 180-185.

38 Fujii T, Kitaoka HB, Watanabe K, et al. Comparison of modified Brostrom and Evans procedures in simulated lateral ankle injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1025-1031.

39 Krips R, Brandsson S, Swensson C, et al. Anatomical reconstruction and Evans tenodesis of the lateral ligaments of the ankle. Clinical and radiological findings after follow-up for 15 to 30 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:232-236.

40 Juliano PJ, Jordan JD, Lippert FG, et al. Persistent postoperative pain after the Chrisman-Snook ankle reconstruction. Am J Orthop. 2000;29:449-452.

41 Horstman JK, Kantor GS, Samuelson KM. Investigation of lateral ankle ligament reconstruction. Foot Ankle. 1981;1:338-342.

42 Labs K, Perka C, Lang T. Clinical and gait-analytical results of the modified Evans tenodesis in chronic fibulotalar ligament instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9:116-122.

43 Nimon GA, Dobson PJ, Angel KR, et al. A long-term review of a modified Evans procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:14-18.

44 Becker HP, Rosenbaum D, Zeithammer G, et al. Gait pattern analysis after ankle ligament reconstruction (modified Evans procedure). Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:477-482.

45 Orava S, Jaroma H, Weitz H, et al. Radiographic instability of the ankle joint after Evans’ repair. Acta Orthop Scand. 1983;54:734-738.

46 Boszotta H, Sauer G. [Chronic fibular ligament insufficiency at the upper ankle joint. Late results after modified Watson-Jones plastic surgery]. Unfallchirurg. 1989;92:11-16.

47 van der Rijt AJ, Evans GA. The long-term results of Watson-Jones tenodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984;66:371-375.

48 Hennrikus WL, Mapes RC, Lyons PM, et al. Outcomes of the Chrisman-Snook and modified-Broström procedures for chronic lateral ankle instability. A prospective, randomized comparison. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:400-404.

49 Harper MC. Modification of the Gould modification of the Broström ankle repair. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:788.

50 Broström L. Sprained ankles. VI. Surgical treatment of “chronic” ligament ruptures. Acta Chir Scand. 1966;132:551-565.

51 Karlsson J, Bergsten T, Lansinger O, et al. Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle for chronic lateral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:581-588.

52 Gould N, Seligson D, Gassman J. Early and late repair of lateral ligament of the ankle. Foot Ankle. 1980;1:84-89.

53 Ajis A, Younger AS, Maffulli N. Anatomic repair for chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:539-545.

54 Karlsson J, Rudholm O, Bergsten T, et al. Early range of motion training after ligament reconstruction of the ankle joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1995;3:173-177.

55 Pijnenburg AC, Bogaard K, Krips R, et al. Operative and functional treatment of rupture of the lateral ligament of the ankle. A randomised, prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:525-530.

56 Jarde O, Duboille G, Abi-Raad G, et al. [Ankle instability with involvement of the subtalar joint demonstrated by MRI. Results with the Castaing procedure in 45 cases.]. Acta Orthop Belg. 2002;68:515-528.

57 Karlsson J, Eriksson BI, Renstrom P. Subtalar instability of the foot. A review and results after surgical treatment. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1998;8:191-197.

58 Rudert M, Wulker N, Wirth CJ. Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle using a regional periosteal flap. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:446-451.

59 Liu SH, Jacobson KE. A new operation for chronic lateral ankle instability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:55-59.

60 Duquennoy A, Fontaine C, Martinot JC, et al. [Surgical reduction of the external ligament for chronic instability of the tibio-tarsal joint. Apropos of 58 reviewed cases]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1989;75:387-393.

61 Duquennoy A, Letendard J, Loock P. [Chronic instability of the ankle treated by reefing of the lateral ligament (author’s transl)]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1980;66:311-316.

62 Messer TM, Cummins CA, Ahn J, et al. Outcome of the modified Broström procedure for chronic lateral ankle instability using suture anchors. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:996-1003.

63 Hamilton WG, Thompson FM, Snow SW. The modified Broström procedure for lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle. 1993;14:1-7.

64 Busconi BD, Pappas AM. Chronic, painful ankle instability in skeletally immature athletes. Ununited osteochondral fractures of the distal fibula. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:647-651.

65 Danielsson LG. Avulsion fracture of the lateral malleolus in children. Injury. 1980;12:165-167.

66 Letts M, Davidson D, Mukhtar I. Surgical management of chronic lateral ankle instability in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:392-397.

67 Cheng M, Tho KS. Chrisman-Snook ankle ligament reconstruction outcomes—a local experience. Singapore Med J. 2002;43:605-609.

68 Colombet P, Bousquet V, Allard M, et al. [Treatment of chronic ankle instability with the Chrisman-Snook’s technique]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1999;85:722-726.

69 Eskander M, Macdonald R. Watson-Jones tenodesis for chronic ankle joint instability. J R Army Med Corps. 1993;139:115-116.

70 Lauttamus L, Korkala O, Tanskanen P. Lateral ligament injuries of the ankle. Surgical treatment of late cases. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1982;71:164-167.

71 Kristiansen B. Surgical treatment of ankle instability in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 1982;16:40-45.

72 Kristiansen B. Evans’ repair of lateral instability of the ankle joint. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52:679-682.

73 Smith PA, Miller SJ, Berni AJ. A modified Chrisman-Snook procedure for reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle: Review of 18 cases. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:259-266.

74 Marsh JS, Daigneault JP, Polzhofer GK. Treatment of ankle instability in children and adolescents with a modified Chrisman-Snook repair: A clinical and patient-based outcome study. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:94-99.

75 Rosenbaum D, Engelhardt M, Becker HP, et al. Clinical and functional outcome after anatomic and nonanatomic ankle ligament reconstruction: Evans tenodesis versus periosteal flap. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:636-639.

76 Hedeboe J, Johannsen A. Recurrent instability of the ankle joint. Surgical repair by the Watson-Jones method. Acta Orthop Scand. 1979;50:337-340.

77 Karlsson J, Bergsten T, Lansinger O, et al. Lateral instability of the ankle treated by the Evans procedure. A long-term clinical and radiological follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:476-480.

78 Boyer DS, Younger AS. Anatomic reconstruction of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle using a gracilis autograft. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:585-595.

79 Segesser B, Goesele A. [Weber fibular ligament-plasty with plantar tendon with Segesser modification]. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 1996;10:88-93.

80 Colville MR, Grondel RJ. Anatomic reconstruction of the lateral ankle ligaments using a split peroneus brevis tendon graft. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:210-213.

81 Solheim LF, Denstad TF, Roaas A. Chronic lateral instability of the ankle. A method of reconstruction using the Achilles tendon. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51:193-196.

82 Sugimoto K, Takakura Y, Kumai T, et al. Reconstruction of the lateral ankle ligaments with bone-patellar tendon graft in patients with chronic ankle instability: A preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:340-346.

83 Coughlin MJ, Schenck RCJr, Grebing BR, et al. Comprehensive reconstruction of the lateral ankle for chronic instability using a free gracilis graft. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:231-241.

84 Anderson ME. Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle using the plantaris tendon. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:930-934.

85 Kuhn MA, Lippert FG. Revision lateral ankle reconstruction. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:77-81.

86 Sammarco GJ, Carrasquillo HA. Surgical revision after failed lateral ankle reconstruction. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:748-753.

87 Kerkhoffs GM, Handoll HH, de Bie R, et al. Surgical versus conservative treatment for acute injuries of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.; 2; 2007; CD000380.