Chapter 68 What Is the Best Treatment for Posterior Tibial Tendonitis?

Posterior tibial tendonitis, also known as posterior tibial tendon dysfunction (PTTD), is a well-recognized clinical entity that encompasses a spectrum of disease ranging from inflammation to frank insufficiency and rupture of the tendon. Dysfunction of the posterior tibial tendon (PTT) has been found to be the leading cause of a flatfoot deformity1 and can cause significant impairment of the affected extremity.2 The diagnosis of PTT dysfunction is often delayed or missed. Increased awareness and knowledge of the presentation of this disease entity can help improve rates of diagnosis. The treatment of PTTD is an evolving area with several potential treatment options. Although both surgical and nonsurgical options have been investigated, controversy still exists regarding the ideal treatment for PTTD. This chapter aims to simplify some of the debate surrounding this topic.

STAGING

PTT dysfunction is classically divided into three clinical stages corresponding to the progression of the disease and used to guide treatment.3,4 This classification system was modified to include a fourth stage by Myerson.5 Stage I is characterized by mild swelling and medial ankle pain but no deformity when compared with the unaffected side. The patient retains the ability to single-leg heel rise. Stage II is characterized by progressive flattening of the arch, with a flexible valgus heel deformity. In this stage, the patient is unable to perform single-leg heel rise or invert against resistance. Stage III includes the signs of stage II, but the hindfoot deformity is fixed in valgus with forefoot abduction. Degenerative changes of the midfoot and subtalar joint are also present on radiographs. Stage IV is characterized by valgus tilt of the talus in the ankle mortise leading to lateral tibiotalar degeneration.

STAGE I

Nonoperative Therapy

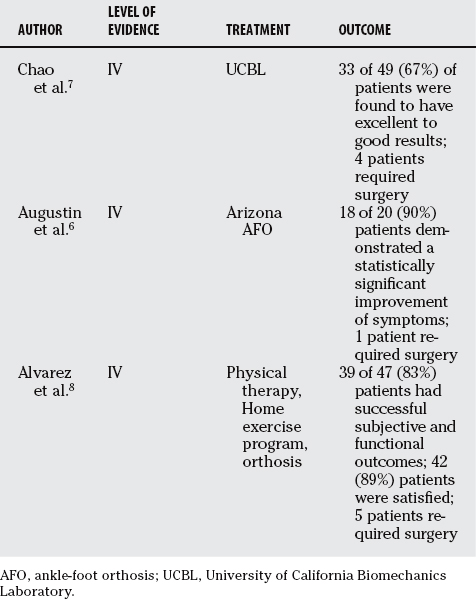

Nonoperative therapy (Table 68-1) is an appropriate initial intervention in almost all cases of PTTD. The goals of treatment are pain relief and the return of PTT function when possible. In a flexible deformity, the aim is to control the progressive valgus deformity of the hindfoot. In a rigid deformity, the goal is to support the position of the foot in situ with a brace that accommodates the bony deformities. In addition, symptomatic relief can be addressed with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, activity modification, and encouraging weight loss.

Few studies exist on the nonoperative treatment of PTT dysfunction, but it is believed that a well-fitted, custom-molded orthosis can be effective at relieving symptoms, and can delay and sometimes prevent surgical intervention6 (Level of Evidence V). Chao and colleagues7 performed a study of 49 patients with the diagnosis of PTTD treated with either a molded ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) or University of California Biomechanics Laboratory (UCBL) brace with medial posting (Level IV). Nonobese patients with flexible deformities and less than 10-degree residual forefoot varus with the heel in a neutral position received the UCBL brace. The remaining patients received the molded AFO. In total, 40 feet were treated with a molded AFO, and 13 were treated with a UCBL brace. Patients were divided into three groups based on a functional scoring system, and 67% of patients were found to have excellent to good results. Unfortunately, this study cannot be used to make a comparison between different disease stages because of the nonuniformity of treatment.

Augustin and coworkers6 studied the nonoperative treatment of various stages of PTTD with an Arizona AFO brace, a custom-molded leather and polypropylene orthosis (Level IV). Twenty-one patients with PTTD were evaluated just before brace use and after a minimum of 3 months of use using questionnaires and clinical examination. American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) Hindfoot Scores, Foot Function Index scores, and 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) scores all increased significantly except for the change in health perception area of the SF-36. Six of six patients with stage I PTTD showed improvement attributable to the brace. The authors suggest that the Arizona AFO brace is effective at relieving symptoms and either obviating or delaying any surgical intervention, especially in earlier stages. Further studies are needed to determine whether an orthosis can prevent disease progression together with providing symptomatic relief.

Alvarez and coauthors8 studied the treatment of stage I and II PTTD in 47 patients with a nonoperative management protocol consisting of physical therapy, an aggressive home exercise program, and an orthosis (Level IV). Over a 4-month period, 39 (83%) patients had successful subjective and functional outcomes, and 42 (89%) patients were satisfied, with 5 (11%) patients requiring surgery.

Operative Treatment

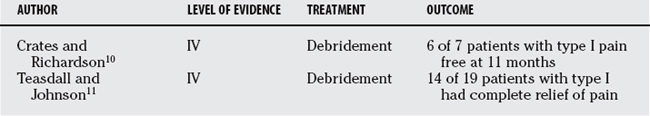

A variety of surgical options exists for patients who do not respond to a trial of conservative treatment. The principal of operative treatment is to perform the least invasive procedure that will decrease pain and improve function.9 For stage I PTTD exploration and debridement of the PTT and soft tissue is often a recommended option. (Table 68-2). All tenosynovial tissue should be excised, with debridement of degenerated tendon areas and repair of any tears. Crates and Richardson10 report on a series of seven patients with stage I PTT dysfunction who were treated with debridement after failure of conservative treatment (Level IV). Six of the seven patients were pain free at 11-month follow-up examination. In Teasdall and Johnson’s study,11 14 of 19 patients had complete relief of pain after a synovectomy and debridement for stage I PTTD (Level IV). Sixteen patients had a return of function of the PTT as evidenced by the ability to perform a single-limb heel-rise test. Significant pathology within the substance of the tendon may require aggressive resection followed by flexor digitorum longus (FDL) transfer and Achilles lengthening to augment the PTT.

STAGE II

Nonoperative Treatment

Initially, stage II PTTD is treated similarly to stage I, but there are a few studies for nonoperative treatment of more advanced PTTD. Because the foot is flexible, corrective orthoses are utilized to prevent or correct deformity and control pain.12 Alvarez and coauthors8 showed improvement in functional and subjective outcomes in patients with stage II PTTD with physical therapy, an aggressive home exercise program, and an orthosis (Level IV). If corrective orthoses are unable to correct the deformity, a medial posted UCBL device, as suggested by Chao and colleagues,7 may be used. Augustin and coworkers6 showed that all 12 patients using an Arizona brace showed pain relief referable to the brace and improvement in multiple clinical measurement instruments. If the deformity is severe, an AFO may be needed.7 As in stage I, stage II is given a 3- to 6-month trial before advocating surgical intervention.

Operative Treatment

A variety of options exists for the operative treatment of stage II PTT dysfunction. An FDL transfer is an accepted option,13 but isolated FDL transfer has failed to demonstrate long-term durability despite short-term success.14 A bony procedure will oftentimes be necessary to supplement the FDL transfer to improve its longevity. Bony procedures can be divided by position and include medial osteotomy, lateral column lengthening, or a combined procedure.

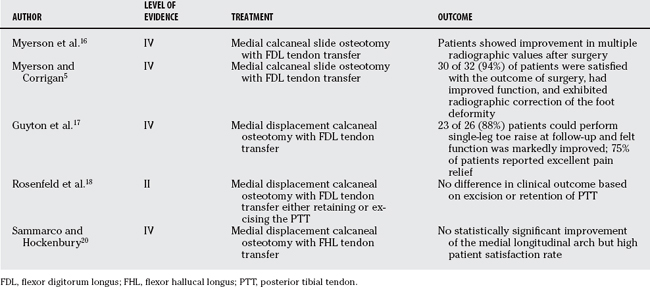

Medial Osteotomy with Flexor Digitorum Longus Transfer

A medial calcaneal slide osteotomy and FDL tendon transfer is one surgical option that has been shown to provide acceptable results for stage II disease (Table 68-3).15 Myerson and researchers16 performed a radiographic analysis of 18 patients 12 to 26 months after such a procedure (Level IV). They found improved radiographic values of the talar-first metatarsal angle and the distance from the medial cuneiform to the floor, concluding that the procedure may offset the weakness of isolated FDL transfer. Myerson and researchers16 also found high patient satisfaction and functional improvement in 32 patients treated with this procedure for stage II disease at a mean of 20 months after surgery (Level IV).5 Guyton and coworkers17 performed a review of 26 patients who underwent the procedure at a mean of 32 months follow-up (Level IV). All patients except three were able to perform a single-leg toe raise, which none could perform before surgery. Pain relief was rated as excellent by 75% of patients. Patients felt a prolonged period of steady improvement in symptoms and function over time. Radiographic improvement in the alignment of the foot was noted but did not correlate to self-reported improvement in appearance. These early clinical studies suggest that FDL transfer and medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy provide good functional outcome and symptomatic relief.

The decision to remove or retain the PTT when performing a FDL tendon transfer and medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy has been examined. Rosenfeld and investigators18 performed a prospective study randomizing 12 patients into 2 groups depending on excision or retention of the PTT, and assessed muscle volume and AOFAS scores at 1-year follow-up (Level II). Though the intact tendon group lost posterior tibial muscle volume, all of the posterior tibial muscles in the excised tendon group were replaced by fatty infiltration. The FDL muscle hypertrophied to a greater extent in the excised tendon group, but there was no difference in AOFAS scores between the two groups after surgery. The authors conclude that the FDL undergoes greater hypertrophy and the posterior tibia undergoes fatty infiltration with excision of the PTT, but this does not affect clinical outcome.

Medial Osteotomy with Flexor Hallucal Longus Transfer

Commonly, the FDL tendon has been used in tendon transfer for PTT dysfunction, but this choice has been questioned. The FDL is only 28% of the relative strength of PTT and only 69% of the strength of the antagonistic peroneal brevis (PB). The flexor hallucis longus (FHL) has 50% of the relative strength of the PTT and exceeds the strength of the PB.19 Sammarco and Hockenbury20 hypothesize that using a stronger muscle would lead to a greater arch correction (Level IV). They retrospectively analyzed a series of 19 patients undergoing an FHL tendon transfer and medial calcaneal osteotomy for stage 2 PTTD. The clinical outcomes using this technique were comparable with those observed in a series of FDL tendon transfer and calcaneal osteotomy, and no improvement was shown in radiographic appearance of the medial longitudinal arch. Despite the new interest in FHL transfer procedures, short-term results have failed to reveal superiority of the FHL to FDL transfer with calcaneal osteotomy. In addition, the FHL tendon requires a more complicated dissection, which places the neurovascular bundle under greater risk.

Lateral Osteotomy

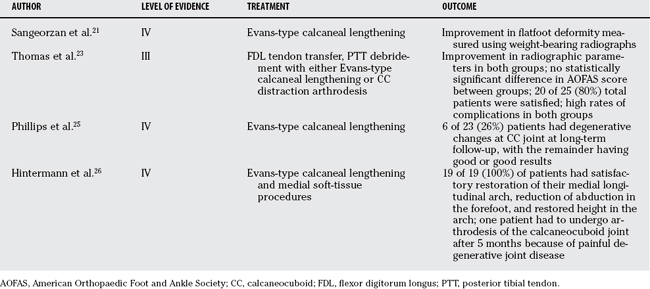

Another option for stage II dysfunction is lateral column lengthening in conjunction with a tendon transfer (Table 68-4). The lengthening can be performed using an osteotomy of the neck of the calcaneus and interposing bone graft or through the calcaneocuboid (CC) joint itself. A version of the procedure by Evans recommends the osteotomy be done 1.5 cm proximal to the CC joint. Sangeorzan and researchers21 studied the effect of Evans-type calcaneal lengthening on relations among the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot in seven patients who underwent the procedure for symptomatic pes planus (Level IV). The authors note an improvement in the flatfoot deformity. Kitaoka and investigators22 performed a study using a dynamic flatfoot deformity model of nine fresh-frozen foot specimens to investigate their mechanical behavior after CC distraction arthrodesis. Three-dimensional tarsal bone positions were determined using a magnetic tracking system. Arch alignment in simulated toe-off phase of gait was found to be improved significantly but was not reduced anatomically.

No consensus has been reached on the ideal method of lateral column lengthening. Thomas and colleagues23 analyzed 27 feet treated with lateral column lengthening for painful pes planus at 1-year follow-up examination (Level III). Ten feet underwent Evans-type open-wedge osteotomy with tricortical iliac crest graft, and 17 feet underwent CC distraction arthrodesis. Both groups underwent debridement of PTT with FDL transfer. Radiographic results documented marked improvement in all parameters, with no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Postoperative AOFAS rating score also did not show a statistically significant difference. Twenty of 25 patients in both groups were satisfied, and 96% stated they would have the same surgery again. Of note was a high rate of complications for both groups, specifically the rate of nonunion or delayed union in the CC distraction arthrodesis group. The authors conclude that both procedures offered marked improvement in radiographic parameters and AOFAS score, but both were also associated with a high rate of complications.

Particular concern regarding arthritis of the CC joint with Evans-type procedure has led several authors to recommended abandoning the procedure. The literature, however, is conflicting. A cadaver study demonstrated increased CC joint pressures after an Evans osteotomy with wedge graft.24 In a study from 1983, Phillips and coauthors25 report degenerative changes in CC joint in 6 of the 23 feet (Level IV). A more recent study by Hintermann and coworkers26 reviewed 19 patients who underwent lateral column lengthening by calcaneal osteotomy in conjunction with medial soft-tissue procedures (Level IV). At an average follow-up of 23 months, 2 patients had radiographic signs of CC degeneration, and all 19 patients had satisfactory restoration of the medial arch height. One patient required arthrodesis of the CC joint after 5 months because of painful degenerative joint disease. In addition, Momberger and coworkers27 examined the change in pressure across the CC joint after an Evans-type calcaneal osteotomy using a cadaveric adult flatfoot model. Joint pressures were compared among the normal foot, the created flatfoot, and the corrected flatfoot. Peak pressure across the joint increased significantly from the normal to the created flatfoot but did not change significantly from the flatfoot to the corrected flatfoot model. In some cases, the peak pressure in the flatfoot decreased with correction. These findings led the authors to conclude that the Evans-type osteotomy does not increase pressure across the CC joint. The literature provides an inconclusive picture of the superior method and precludes abandonment of the Evans-type osteotomy.

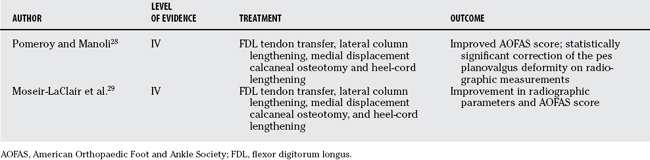

Combined Medial and Lateral Osteotomies

A technique of combining medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy, lateral column lengthening, FDL transfer, and heel cord lengthening has gained interest (Table 68-5). Pomeroy and Manoli28 performed this procedure in 20 cases of stage II PTT dysfunction, and analyzed the patients radiographically and with the AOFAS scale at an average follow-up of 17.5 months (Level IV). The average foot rating improved from 51.4 to 82.8, and radiographic measurements demonstrated statistically significant correction of the pes planovalgus deformity. Moseir-LaClair and researchers29 analyzed the effect of a similar procedure in 26 patients with 28 stage II feet at a mean follow-up of 5 years (Level IV). The AOFAS score was high after surgery, and there was radiographic improvement of the deformity. Four patients (14%) demonstrated signs of CC arthrosis, but the authors contend that half of these patients had preexisting CC joint arthritis. The authors of both studies suggest that the double osteotomy technique provides symptomatic relief and acceptable correction of pes planovalgus deformity associated with stage 2 PTTD.

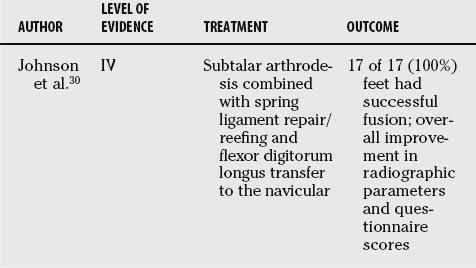

Subtalar Fusion

Another proposed operative procedure for stage II PTTD consists of subtalar fusion in conjunction with soft-tissue rebalancing (Table 68-6). Johnson and investigators30 performed a retrospective review of 17 feet with stage II PTT dysfunction treated with subtalar arthrodesis combined with spring ligament repair/reefing and FDL transfer at an average follow-up period of 27 months (Level IV). All patients had successful subtalar joint fusion with an average time to radiographic union of 10.1 weeks. Standing radiographic analysis demonstrated an improvement in the anteroposterior talo-first metatarsal angle, the talonavicular coverage angle, and the medial cuneiform distance to the floor. These early results suggest that FDL transfer with medial soft-tissue reconstruction and subtalar fusion have comparable results with other extra-articular sparing procedures. The authors suggest that this procedure can be an effective and reliable alternative procedure in the treatment of stage II PTT dysfunction.

STAGES III AND IV

Nonoperative Treatment

In stage III and IV, the foot is rigid, and the goal is to provide support, reduce pain, and prevent further progression. Augustin and coworkers6 showed that three of five patients with stage III PTTD had relief of symptoms referable to the use of an Arizona brace. The foot may be braced in situ with a custom-molded orthosis. Although a solid AFO may sometimes prove useful, often an articulated device is better tolerated. In stage IV disease, a solid device is usually required because orthoses usually provide little control of the deformity.31 With the use of braces, particular care must be taken to avoid skin ulceration, which can be caused by the rigidity of the deformity. Although various conservative modalities have been described, advanced PTTD is difficult to manage without surgery.31

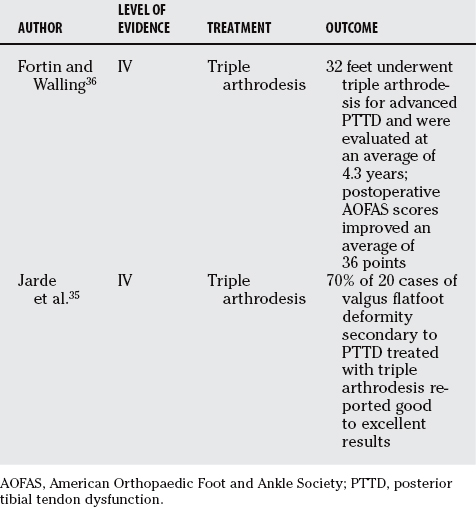

Operative Treatment

The standard treatment for stage III PTTD remains arthrodesis, although there is debate over the extent of fusion (Table 68-7). Traditionally, the gold standard for treatment of stage III PTTD has been triple arthrodesis32,33 (Level V). Multiple studies have shown satisfactory results with this procedure, although there is the long-term risk for adjacent ankle arthritis.34,35 Fortin and Walling36 studied 32 patients who underwent triple arthrodesis for advanced PTTD and found that Foot and Ankle Society Hindfoot scores improved an average of 36 points with high patient satisfaction (Level IV). Jarde and colleagues35 performed a retrospective review of 20 cases of flatfoot deformity secondary to PTTD and found good to excellent results in 70%, although follow-up radiographs showed progression of osteoarthritis (Level IV). The fusion technique should be meticulous and preceded with an anatomic reduction because an in situ fusion carries the risk for future arthrosis at the adjacent joints.14 Isolated subtalar fusion has been suggested as an alternative in selected groups, but data are limited and it requires further study.37

Stage IV dysfunction is a rare anatomic condition with no specific gold standard. Described treatment modalities include tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis or pan-talar fusion, although few reports with these techniques in patients with PTTD have been published.31,38 Experience with these procedures in other patient populations, such as arthritic or post-traumatic conditions, has shown that they are viable salvage procedures when there is disease involving both the subtalar and tibiotalar compartments.39,40

SUMMARY

The PTT is a vital component of the lower extremity, and its dysfunction can lead to significant deformity and pain. PTT dysfunction is a clinical diagnosis in which the physical examination can help differentiate the disease into its various stages, depending on the presence and flexibility of deformity. Nearly all cases initially can be managed without surgery, but progression of disease or continuing pain will many times necessitate a surgical intervention. A variety of surgical procedures exists for the treatment of PTT dysfunction, and often there is no definitive standard of treatment. Both the conservative and surgical options are evolving areas with ample opportunity for future research. (Table 68-8).

| RECOMMENDATIONS | STAGE | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

| Activity modification, anti-inflammatories, immobilization alone | I | C |

| Orthosis | C | |

| Surgical exploration with soft tissue debridement | C | |

| AFO/UCBL | II | C |

| Medial osteotomy with FDL/FHL transfer | C | |

| Lateral lengthening with FDL transfer | C | |

| Combined procedures | C | |

| Subtalar arthrodesis with soft-tissue procedures | C | |

| Custom-molded orthosis | III | C |

| Triple arthrodesis | C | |

| Custom-molded orthosis | IV | I |

| Tibiocalcaneal arthrodesis | C |

AOFAS, American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society; PTTD, posterior tibial tendon dysfunction.

1 Geideman WM, Johnson JE. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:68-77.

2 Mann RA. Acquired flatfoot in adults. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 181; 1983; 46-51.

3 Johnson KA, Strom DE. Tibialis posterior tendon dysfunction. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 239; 1989; 196-206.

4 Beals TC, Pomeroy GC, Manoli A2nd. Posterior tendon insufficiency: Diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:112-118.

5 Myerson MS, Corrigan J. Treatment of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with flexor digitorum longus tendon transfer and calcaneal osteotomy. Orthopedics. 1996;19:383-388.

6 Augustin JF, et al. Nonoperative treatment of adult acquired flat foot with the Arizona brace. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8:491-502.

7 Chao W, et al. Nonoperative management of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:736-741.

8 Alvarez RG, et al. Stage I and II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction treated by a structured nonoperative management protocol: an orthosis and exercise program. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:2-8.

9 Myerson MS. Adult acquired flatfoot deformity: Treatment of dysfunction of the posterior tibial tendon. Instr Course Lect. 1997;46:393-405.

10 Crates JM, Richardson EG. Treatment of stage I posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with medial soft tissue procedures. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 365; 1999; 46-49.

11 Teasdall RD, Johnson KA. Surgical treatment of stage I posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:646-648.

12 Wapner KL, Chao W. Nonoperative treatment of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 365; 1999; 39-45.

13 Funk DA, Cass JR, Johnson KA. Acquired adult flat foot secondary to posterior tibial-tendon pathology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:95-102.

14 Early J. Issues relating to failure in the treatment of posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8:637-645.

15 Hockenbury RT, Sammarco GJ. Medial sliding calcaneal osteotomy with flexor hallucis longus transfer for the treatment of posterior tibial tendon insufficiency. Foot Ankle Clin. 2001;6:569-581.

16 Myerson MS, et al. Tendon transfer combined with calcaneal osteotomy for treatment of posterior tibial tendon insufficiency: A radiological investigation. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16:712-718.

17 Guyton GP, et al. Flexor digitorum longus transfer and medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy for posterior tibial tendon dysfunction: A middle-term clinical follow-up. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:627-632.

18 Rosenfeld PF, Dick J, Saxby TS. The response of the flexor digitorum longus and posterior tibial muscles to tendon transfer and calcaneal osteotomy for stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:671-674.

19 Silver RL, de la Garza J, Rang M. The myth of muscle balance. A study of relative strengths and excursions of normal muscles about the foot and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:432-437.

20 Sammarco GJ, Hockenbury RT. Treatment of stage II posterior tibial tendon dysfunction with flexor hallucis longus transfer and medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:305-312.

21 Sangeorzan BJ, Mosca V, Hansen STJr. Effect of calcaneal lengthening on relationships among the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot. Foot Ankle. 1993;14:136-141.

22 Kitaoka HB, et al. Calcaneocuboid distraction arthrodesis for posterior tibial tendon dysfunction and flatfoot: A cadaveric study. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 381; 2000; 241-247.

23 Thomas RL, et al. Preliminary results comparing two methods of lateral column lengthening. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:107-119.

24 Cooper PS, Nowak MD, Shaer J. Calcaneocuboid joint pressures with lateral column lengthening (Evans) procedure. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:199-205.

25 Phillips GE. A review of elongation of os calcis for flat feet. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1983;65:15-18.

26 Hintermann B, Valderrabano V, Kundert HP. Lengthening of the lateral column and reconstruction of the medial soft tissue for treatment of acquired flatfoot deformity associated with insufficiency of the posterior tibial tendon. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:622-629.

27 Momberger N, et al. Calcaneocuboid joint pressure after lateral column lengthening in a cadaveric planovalgus deformity model. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:730-735.

28 Pomeroy GC, Manoli A2nd. A new operative approach for flatfoot secondary to posterior tibial tendon insufficiency: a preliminary report. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:206-212.

29 Moseir-LaClair S, Pomeroy G, Manoli A2nd. Intermediate follow-up on the double osteotomy and tendon transfer procedure for stage II posterior tibial tendon insufficiency. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:283-291.

30 Johnson JE, et al. Subtalar arthrodesis with flexor digitorum longus transfer and spring ligament repair for treatment of posterior tibial tendon insufficiency. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:722-729.

31 Bohay DR, Anderson JG. Stage IV posterior tibial tendon insufficiency: The tilted ankle. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8:619-636.

32 Kelly IP, Easley ME. Treatment of stage 3 adult acquired flatfoot. Foot Ankle Clin. 2001;6:153-166.

33 Maskill MP, et al. Triple arthrodesis for the adult-acquired flatfoot deformity. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2007;24:765-778.

34 Graves SC, Mann RA, Graves KO. Triple arthrodesis in older adults. Results after long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:355-362.

35 Jarde O, et al. [Triple arthrodesis in the management of acquired flatfoot deformity in the adult secondary to posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. A retrospective study of 20 cases]. Acta Orthop Belg. 2002;68:56-62.

36 Fortin PT, Walling AK. Triple arthrodesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 365; 1999; 91-99.

37 Laughlin TJ, Payette CR. Triple arthrodesis and subtalar joint arthrodesis. For the treatment of end-stage posterior tibial tendon dysfunction. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1999;16:527-555.

38 Kelly IP, Nunley JA. Treatment of stage 4 adult acquired flatfoot. Foot Ankle Clin. 2001;6:167-178.

39 Chou LB, et al. Tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:804-808.

40 Papa JA, Myerson MS. Pantalar and tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis for post-traumatic osteoarthrosis of the ankle and hindfoot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:1042-1049.