Chapter 66 What Is the Best Treatment for Pilon Fractures?

Intra-articular fractures of the distal tibia vary in regards to the amount of articular and metaphyseal damage. Pilon fractures are difficult injuries to manage and can be associated with high rates of complications, chronic pain, and disability. The underlying mechanism of injury and general physiology of the patient dictates the severity of the bony injury and, more importantly, the soft-tissue involvement. High-energy pilon fractures are the most challenging to manage.

IMAGING AND ANATOMY

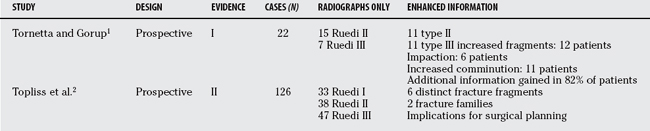

After appropriate radiographs, computed tomography (CT) is important in operative planning (Table 66-1). Tornetta and Gorup1 have shown that their operative plan was altered in 64% of patients, with additional information about fracture pattern gained in 82%, underlining the importance of appropriate imaging. Understanding the anatomy of the fracture should allow the development of appropriate steps in fracture fragment approach and reduction, improving surgical technique and ultimately outcome.

Recent work from Bristol2 documents 126 pilon fractures, and defines 6 distinct fracture fragments (anterior, posterior, medial, anterolateral, posterolateral, and die-punch) and 2 fracture families (sagittal and coronal). Within each fracture group there was progression from a simple to a more complex type with increasing transfer of energy. Interestingly, a pilon fracture with an intact distal fibula was eight times more likely to have a functional disruption of the tibiofibular joint (separated lateral tibial fragments), and if not recognized, resulted in continued instability and its associated complications. The reproducibility of this fracture description was found by Topliss and colleagues2 to be superior to the AO and Ruedi and Allgower’s3 classification concerning interobserver and intraobserver agreement. The authors conclude that the sagittal family fractures occur after high energy, with varus angulation in young-er patients, whereas the coronal fractures occur with valgus angulation in older patients after less severe trauma. This work has implications for surgical approach, reduction of fracture fragments, and choice of implant.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The surgical strategies can be divided into three broad subsets:

EVIDENCE

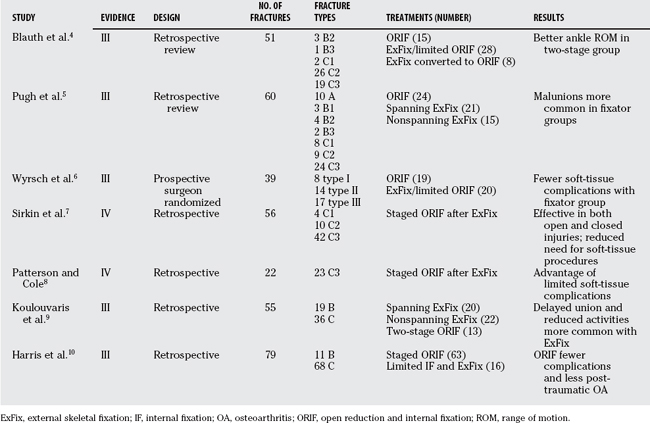

Several studies have been published that aim to compare the differing treatment modalities for pilon fractures, but all have their limitations when conclusions are drawn from limited sample size and variable patient conditions (Table 66-2).

Blauth and colleagues4 retrospectively studied 51 patients. They had 3 treatment groups: primary ORIF (15 patients all with closed injuries), definitive ExFix with or without limited internal fixation (28 patients), and temporary ExFix with or without limited internal fixation followed by delayed minimally invasive medial plating (8 patients). The incidence of wound infections did not differ significantly among the three groups. The range of ankle movement was greater in the two-stage treated group compared with the others. These patients also had less pain, more frequently continued working in their previous profession, and had fewer limitations in their leisure activities. On the basis of these findings, the authors recommend a two-stage procedure. However, the sample size is small in this retrospective review, and the groups are not well matched; therefore, definitive conclusions cannot be made.

Similar work by Pugh and coauthors5 retrospectively assessed 60 pilon fractures. Again, there were 3 broad groups: 24 patients treated with ORIF, 21 patients treated with an ankle-spanning half-pin ExFix, and 15 patients with a single-ring hybrid ExFix. The severity of injuries was similar in all groups. No significant difference was reported in complications between groups, but a greater number of malunions occurred in fractures treated with ExFix compared with ORIF (P = 0.03). These findings were uninfluenced by whether the fracture was open or closed, was bone grafted, or had an associated fibula fracture stabilized. The authors conclude that external fixation had a lower risk for deep infection but a greater risk for malunion than did ORIF. No randomization, long-term follow-up, or functional outcome was performed in these patients.

A surgeon randomized, prospective study6 evaluated 39 patients. Nineteen patients underwent ORIF of both tibia and fibula, and 20 patients had ExFix with or without limited internal fixation. The authors aimed to compare the rates of complications, the radiologic results, and the functional results between the two groups. In the ORIF group, there were 28 additional operations in 7 patients with 15 major complications compared with 5 additional operations in 4 patients with 4 major complications in the ExFix group. They found that nonvalidated clinical score (pain and range of motion) did not correlate well with type of fracture, and there was also no significant difference between treatment groups. The conclusion was that ExFix is a satisfactory method of treatment associated with fewer complications than ORIF. However, of note is the timing of surgery in the ORIF group, and this point should be highlighted. Operating in the presence of severe intradermal edema or fracture blisters can further compromise damaged soft tissues. On average, patients were operated on days 3 to 5, when soft-tissue swelling was well established. Therefore, it may well not be technique related but timing dependent.

This point has been examined by work from Sirkin and colleagues.7 They retrospectively analyzed 56 pilon fractures (34 closed and 22 open fractures) from a single institution. All patients underwent immediate ORIF of the fibula and closed reduction with spanning ExFix for the distal tibia. Formal ORIF of the tibia was performed when soft-tissue swelling had subsided, on average, 14 days after injury. By following a staged protocol, they demonstrated that ORIF could be performed semielectively with a low risk for wound problem in both open and closed injuries. However, no functional outcome scoring of results with this effective soft-tissue–preserving procedure exists.

Similar retrospective work from Florida (Patterson and Cole8) examined 22 C3 distal tibia fractures treated with a comparable staged protocol. Anatomic reduction was possible in 73% of patients who underwent surgery, on average, 24 days after injury. Approximately 90% of patients had good/fair results on subjective and objective evaluation. The authors recognized difficulties with operating on 3-week-old fractures and the extended dissection needed.

Koulouvaris and coworkers9 retrospectively compared ExFix with staged ORIF. The study population included 36 AO type C and 19 AO type B tibial plafond fractures. Of these fractures, 24 were open and 31 closed. Three surgical protocols were used. In 20 patients, group A, a half-pin ExFix with ankle spanning was used for fixation. In 22 patients, group B, a non-spanning ring hybrid ExFix was used. In 13 patients, group C, a two-staged ORIF was performed. Group A had union in 6.9 months, group B in 5.6 months, and group C in 5.1 months (P = 0.009). Six (group A), two (group B), and one (group C) patient had limitation of ankle motion (P = 0.47). One patient from group C acquired an infection, and the plate was removed. Four (group A), one (group B), and one (group C) patients have experienced development of post-traumatic arthritis (defined as loss of joint space and pain) (P = 0.25). Seven patients from group A have reduced their activities (P = 0.004). In this long-term follow-up study, the two-staged internal fixation and the hybrid fixation with small arthrotomy were equally efficacious in achieving bone union. Patients in external fixation with the ankle spanning had a significantly greater rate of delayed union. Also, more patients in this group had to reduce their activities.

Similar work from Cleveland (Harris and researchers10) retrospectively reviewed 79 pilon fractures. Patients were treated with ORIF (63 patients) or limited open articular reduction and wire-ring ExFix (16 patients). Tibial ORIF was performed at an average of 7.6 days after injury. Approximately 86% of patients with ORIF treatment underwent staged surgery, whereby initial surgery consisted of fibular fixation and temporary ankle-spanning ExFix or splinting. The patients treated definitively with ExFix had more complications (P = 0.007) and post-traumatic arthritis (P = 0.01) when compared with ORIF. However, this may be because of selection bias because more open injuries and more severely comminuted fractures were managed definitively with external fixation than with ORIF.

Although the optimal management of pilon fractures requires anatomic reduction and restoration of the alignment of the distal tibial articular surface, success or failure is often related more closely to the management of the vulnerable soft-tissue envelope around the fracture and the avoidance of wound complications. The natural history of the soft tissues overlying the distal tibia and ankle is that they are subject to swelling and blistering in the first few hours to days after injury, before gradually recovering some elasticity over a period of around 10 to 14 days. It is recognized that there is an early period after injury where the skin is pliant and is able to withstand open fracture surgery. However, this period is poorly quantified: Published graphs and guidelines continue to be based on anecdotal experience, and there remains considerable disagreement as to whether a “safe period” exists. Then there is a subsequent period of localized edema where the soft tissues are widely considered to be under too great a degree of tension, with compromised tissue perfusion, to allow predictable and safe wound closure and healing. Historically, the enthusiasm for open surgical treatment that followed Ruedi and Allgower’s3 seminal article in 1969 was tempered by subsequent reports of disconcerting rates of wound slough, infection, and osteomyelitis in other centers. Currently, a widespread preference exists for staged treatment whereby after temporary external fixation, definitive surgery is delayed until the end of the period of swelling. Several authorities and standard texts6 advise against surgery in the “early” period.

FUNCTIONAL OUTCOME RESULTS

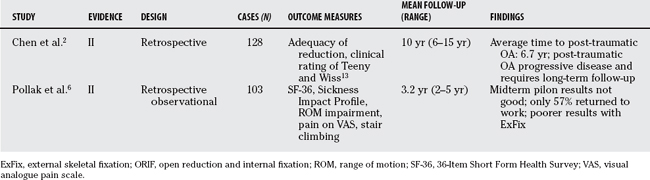

The immediate management of pilon fractures is not the only area of concern for the patient. The long-term function and outcome after such injuries needs to be evaluated to give advice and counseling to patients (Table 66-3).

Although there is good documentation of the complications associated with pilon fractures, functional outcome studies using well-validated assessment tools are scarce in the literature. Ruedi and Allgower’s3 pivotal work with impressive outcomes has not been universally repeated in the current literature.

Pollak and colleagues11 have shown that midterm outcome results after pilon fractures are not good. Their Level II evidence, retrospective, observational study of 103 patients, with a mean duration of follow-up of 3.2 years, showed of those used at time of injury, only 57% returned to work. Approximately one third of patients reported notable difficulty with ankle stiffness (35%), swelling (29%), or pain (33%). Thirteen percent reported that they usually used a walking aid. This was reflected in the Sickness Impact Profile ambulation scores, whereby up to 50% of patients were unable to ascend and descend stairs reciprocally or run on the spot for 30 seconds. Patients treated with ExFix with or without limited internal fixation reported and demonstrated significantly poorer results for three of the five primary outcomes—walking ability, range-of-motion impairment, and pain—than did patients treated with ORIF. In addition to providing evidence about functional outcome, this study also provides strong support for the superiority of ORIF over ankle-spanning ExFix techniques.

More long-term studies related to fracture pattern of pilon fractures, which underwent ORIF, highlight the fact that post-traumatic arthritis is a progressive disease. Chen and coworkers12 studied 128 patients with a mean follow-up period of 10 years (range, 6–15 years). All fractures were treated by ORIF; however, Ruedi and Allgower type II and III injuries underwent delayed surgery after 1 to 2 weeks of traction. At 2 years, the post-traumatic osteoarthritis rate was 5.1%, 9.7%, and 29.6% in types I, II, and III, respectively. There was progression of post-traumatic arthritis only in types II and III to 22.6% and 55.6%, respectively, at final follow-up (mean, 10 years). The average duration between initial injury and the development of severe arthritis was 6.7 years. Functional outcome was worse in patients with high-energy injuries. This study has important implications with regard to resources planning of subsequent patient follow-up, counseling, and possible salvage procedures.

Area of Uncertainty: Timing, Surgical Approach, and Plate Design

The techniques used in the treatment of pilon fractures often depend on the surgeon’s preference and the associated soft-tissue trauma. When faced with a complex pilon fracture and considerable tissue trauma, the most widely accepted treatment option is to apply a spanning external fixator (with or without limited internal of the joint surface) and wait until the swelling abates before proceeding to definitive ORIF. However, intra-articular reduction in the presence of early callus and soft tissues with reduced elasticity further compromise an already challenging operation. Therefore, do we compromise articular reduction for soft-tissue preservation? And does this have a bearing on functional outcome? Insufficient evidence has been presented to make a recommendation about the timing of definitive ORIF, but most current studies advise delay until soft-tissue swelling subsides (7–14 days) by using the staged protocol.

Guidelines

No guidelines have been published about the assessment of treatment of tibial pilon fractures.

In conclusion, the best treatment for tibial pilon fractures is anatomic reduction and stable fixation, whereas respecting the biology of the soft-tissue envelope and allowing early functional rehabilitation. Unfortunately, the literature does not contain good evidence-based studies to support overall superiority of one treatment method. Controversy will continue to exist about the optimum timing and surgical techniques, but the staged protocol for delayed ORIF has the most widespread support at this time. Table 66-4 provides a summary of recommendations for the management of tibial pilon fractures.

TABLE 66-4 Recommendations for the Management of Tibial Pilon Fractures

| RECOMMENDATIONS | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

1 Tornetta P3rd, Gorup J. Axial computed tomography of pilon fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 323; 1996; 273-276.

2 Topliss CJ, Jackson M, Atkins RM. Anatomy of pilon fractures of the distal tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:692-697.

3 Ruedi TP, Allgower M. The operative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the lower end of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 138; 1979; 105-110.

4 Blauth M, Bastian L, Krettek C, et al. Surgical options for the treatment of severe tibial pilon fractures: a study of three techniques. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:153-160.

5 Pugh KJ, Wolinsky PR, McAndrew MP, Johnson KD. Tibial pilon fractures: A comparison of treatment methods. J Trauma. 1999;47:937-941.

6 Wyrsch B, McFerran MA, McAndrew M, et al. Operative treatment of fractures of the tibial plafond. A randomized, prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1646-1657.

7 Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, Herscovici DJr. A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of complex pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2004;18(8 suppl):S28-S32.

8 Patterson MJ, Cole JD. Two-staged delayed open reduction and internal fixation of severe pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 1999;13(2):85-91.

9 Koulouvaris P, Stafylas K, Mitsionis G, et al. Long-term results of various therapy concepts in severe pilon fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007. (Epub ahead of print)

10 Harris AM, Patterson BM, Sontich JK, Vallier HA. Results and outcomes after operative treatment of high-energy tibial plafond fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:256-265.

11 Pollak AN, McCarthy ML, Bess RS, et al. Outcomes after treatment of high-energy tibial plafond fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(10):1893-1900.

12 Chen SH, Wu PH, Lee YS. Long-term results of pilon fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127:55-60.

13 Teeny SM, Wiss DA. Open reduction and internal fixation of tibial plafond fractures. Variables contributing to poor results and complications. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 292; 1993; 108-117.