Chapter 77 What Is the Best Treatment for Injury to the Tarsometatarsal Joint Complex?

The tarsometatarsal joints, commonly but incorrectly called the tarsometatarsal joint, divides the midfoot from the forefoot, and injuries to this joint complex continue to be both a diagnostic and a treatment challenge. The term tarsometatarsal joint complex was introduced by Myerson and colleagues1 to highlight the more extensive nature of this injury to include not only the joints between the metatarsals and cuneiforms or cuboid, but also the intercuneiform and the naviculocuneiform joints. The presentation of this injury is quite varied and may take the form of a joint subluxation, dislocation with or without fracture. Although the reported occurrence is 1 per 55,000 fractures per year,2 these injuries seem to be increasing in frequency since the late 1990s, particularly in certain sports.

Treatment of these injuries does not have uniformly excellent outcomes, even with anatomic reduction and stable internal fixation. Arthritis and hence disability may result even with surgical treatment,3 and the reported prevalence of painful arthrosis with these injuries has ranged from 0 of 9 patients4 to 15 (58%) of 26 patients.5 In a series of 69 patients, degenerative joint disease developed in 21 (30%).6 Regardless of the incidence of post-traumatic arthritis, it is now well accepted that an anatomic reduction is critical to a successful outcome. One such study by Arntz and Hansen7 demonstrated an overall good or excellent functional result in 95% of patients in whom an anatomic reduction was obtained. In contrast, a satisfactory result was obtained in only one of five patients in whom congruity of the joint was not accurately restored.

LEVEL I STUDY

Only a single Level I study has been published on clinical outcomes of surgical treatment of the tarsometatarsal joint. Ly and Coetzee8 compared ORIF versus primary arthrodesis in a study of 41 patients with isolated acute and subacute primarily ligamentous injuries. The average follow-up was 42 months with a minimum of 2 years after treatment. The primary arthrodesis group included a fusion of the first two or three rays, but never included the lateral rays. The mean American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) midfoot score was 68.6 for the open reduction group and was 88 in the arthrodesis group. In the open reduction group, five patients who had persistent midfoot pain with or without the development of deformity eventually underwent arthrodesis. Patients treated with a primary arthrodesis estimated achievement of postoperative level of activity was 92% of their preinjury level, whereas the open reduction group estimated that the postoperative level was only 65% of their preoperative level (P, 0.005). Multiple criticisms have been made for this Level I study. The medium- to long-term results of primary arthrodesis and the risk for arthritis in adjacent joints over the long term remain unknown. Furthermore, significant bony injuries were not addressed in this study because this treatment was based on ligamentous injuries (subluxation and dislocation). Lastly, the inclusion and exclusion criteria are not clear, given that no high-performance athlete was treated in this manner, and no massive and complete high-energy dislocations were treated.

LEVEL II STUDY

Only a single Level II study has been published on tarsometatarsal injuries. In a surgeon randomized study, Mulier and colleagues9 analyzed patients with severe tarsometatarsal injuries who were treated by surgical intervention, with one surgeon always performing an arthrodesis and the other surgeon always performing ORIF. ORIF (16 patients) and partial arthrodesis (6 patients) was recommended over complete arthrodesis of all 5 tarsometatarsal joints (6 patients). The subgroups were identical in age, follow-up, type of fracture, type of injury, and time to intervention. Anatomic reduction was achieved in 8 of the 12 patients in the arthrodesis group and in 12 of the 16 patients in the ORIF group. The Baltimore painful foot score was greater in the ORIF group than in the complete arthrodesis group, meaning the ORIF group had less pain. Stiffness of the forefoot, loss of the metatarsal arch, and sympathetic dystrophy occurred more frequently in the complete arthrodesis group. However, it is noted that 94% of the open-reduction group had signs of radiographic degeneration at the average final follow-up of 30 months.

LEVEL III AND IV STUDIES

Several Level III and IV studies also have been published that provide guidance in decision making. Closed treatment with plaster immobilization has resulted in poor results.10–12 Wilson13 reports that only 1 of 14 patients undergoing closed reduction and cast immobilization had an anatomic reduction, and 7 of the 14 patients were noted to have residual displacement of 5 mm or more. These studies consist of limited small numbers, and their poor results are of historic interest only. The demographics of tarsometatarsal injury have changed markedly, and with closer attention to diagnosis, subtle injuries have been diagnosed with increased frequency. Although closed reduction or closed reduction and percutaneous screw fixation does not allow for assessment under direct visualization of the reduction or for removal of osteocartilaginous debris, percutaneous screw fixation has gained popularity.

Open Reduction and Internal Fixation

Multiple authors have correlated outcomes with the accuracy of surgical reduction. Arntz and Hansen7 retrospectively reviewed 34 tarsometatarsal fracture-dislocations treated with open reduction and temporary internal fixation with AO screws (Level IV). They emphasize the importance of screw fixation, given the previous problems that they had experienced with percutaneous pin fixation, including pin infection, migration of pins, and loss of reduction. Of the patients with an anatomic reduction, a good or excellent result was obtained in all but two patients at an average follow-up of 3.4 years. An analysis of the six patients who had a fair or poor result showed the following: two patients had an anatomic reduction, two patients had a fair reduction, and two a nonanatomic reduction; five had an associated grade II or III open injury.

Kuo and coworkers14 performed a retrospective study of patients who underwent an open reduction and screw fixation of a tarsometatarsal injury (Level IV). Forty-eight patients were observed for an average of 52 months (range, 13–114 months). Twelve patients (25%) had post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the tarsometatarsal joints, and six of them required arthrodesis. The average AOFAS midfoot score was 77 (out of 100). No significant difference in outcome scores could be detected when purely ligamentous injuries were compared with combined ligamentous and osseous injuries, open wounds were compared with closed wounds, involvement of five tarsometatarsal joints was compared with involvement of fewer than five, the presence of associated cuneiform and/or cuboid injury was compared with the absence of either injury, isolated injury was compared with multiple injuries, multiple trauma was compared with the absence of multiple trauma, the presence of associated injury of the ipsilateral lower limb was compared with the absence of such injury, acute diagnosis was compared with delayed diagnosis, and work-related injury was compared with nonwork-related injury. Based on these studies and their levels, grade C recommendation exists for ORIF and screw fixation of tarsometatarsal fracture dislocation.

Late Treatment with Arthrodesis

Delayed treatment of injuries beyond 6 weeks has been associated with poorer outcomes.15 This, however, depends on the magnitude of the deformity. For those injuries associated with complete subluxation of all the joints, then, indeed, delayed treatment is more complicated because the realignment and arthrodesis required is more complex. However, this does not apply to more minor injuries where limited subluxation and dislocation is present. These luxations can be treated months after injury with either closed reduction and percutaneous fixation or ORIF without resorting to arthrodesis. Sangeorzan and Hansen’s19 study of salvage of tarsometatarsal injuries yielded significant results based on different statistical analyses. By Pearson coefficient, they found several significant factors: less time to treatment was more likely to result in a good or excellent result; adequate reduction was correlated with better outcome; and work-related injuries were more likely to have a bad outcome. No correlation was found between the age of the patient and result of treatment. By multiple regression analysis, reduction was the only factor found to be predictive of result.16 Komenda and Myerson17 retrospectively reviewed 32 patients who underwent an arthrodesis of the midfoot after a traumatic injury. The arthrodesis was performed at a mean of 35 months (range, 6–108 months) after the injury. All of the patients were treated with rigid internal fixation, and autogenous bone graft was used in 24 patients in whom a defect had been created after preparation of the bone surfaces. At an average of 50 months after the arthrodesis, the mean AOFAS midfoot postoperative score was 78 points (vs. 44 before surgery). Given the number of patients in this study, it was not possible to determine whether the extent of arthrodesis, the involvement of other joints in the hindfoot or forefoot, or the involvement of workers’ compensation affected outcome.

Primary Arthrodesis

Several Level III and IV studies have analyzed the role of primary arthrodesis for tarsometatarsal dislocation in addition to the Level I study by Ly and Coetzee8 described earlier in this chapter. Granberry and Lipscomb18 recommend primary fusion in any unstable injury requiring open reduction because of the high incidence (11/25) of these injuries subsequently being treated with arthrodesis. However, no information was provided on the type and magnitude of either the injury or the type of treatments available that might have predisposed the patients to development of post-traumatic arthritis. Furthermore, no outcome data were provided subsequently for those 11 patients who underwent arthrodesis. Kuo and coworkers14 suggest that there may be a subset of patients with purely ligamentous injuries who would benefit from primary arthrodesis, given that 6 of 15 of their patients with purely ligamentous injuries experienced development of painful osteoarthrosis.

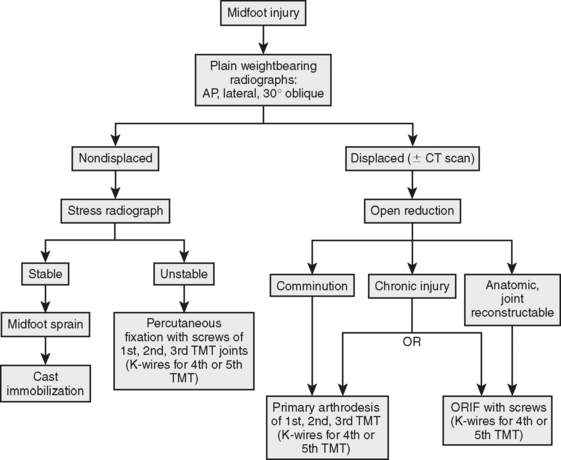

Because of the limited number of grade I/and multiple Level III/IV studies, a Grade C recommendation exists for primary arthrodesis. As noted in the treatment algorithm (Fig. 77-1), we recommend primary arthrodesis in a subset of patients with Lis Franc injuries.

Extent of Arthrodesis

In the setting of arthrosis, the extent of fusion has been an area of controversy, particularly the inclusion versus exclusion of the lateral column. Interestingly, the middle column (second and third metatarsocuneiform joints) has the least motion, and yet are the joints most likely to develop post-traumatic arthritis and require an arthrodesis. The contrary applies to the lateral column (the fourth and fifth metatarsocuboid joints), which is mobile but is rarely symptomatic. The sagittal plane movements of the tarsometatarsal joints, as determined by cadaveric study, are significantly greater for the fourth (9.6 mm) and fifth (10.2 mm), as compared with the first (3.5 mm), second (0.6 mm), and third (1.6 mm) joints.16 Given this increased physiologic motion across the lateral column, the benefit of arthrodesis across these joints has been called into question. In the setting of chronic degenerative changes, Sangeorzan and coauthors19 and Komenda and Myerson17 have recommended that only the medial and/or middle column should be fused. The only two patients who underwent arthrodesis of all three columns in Komenda and Myerson’s study subsequently required a revision procedure with metatarsal osteotomies because of metatarsalgia. Furthermore, a third patient who underwent fusion with an interposition bone block arthrodesis of the calcaneocuboid joint for a traumatic abduction deformity also experienced intractable pain at the metatarsocuboid joints and subsequently underwent metatarsocuboid fusions. Raikin and Schon20 presented a report of 28 feet that were treated with arthrodesis of the fourth and fifth tarsometatarsal joints at a 2-year minimum follow-up, but most of these arthrodeses (22/28) were performed for neurarthopathic rocker-bottom deformity and have no relevance in this type of discussion pertaining to a neurologic intact person with post-traumatic arthritis. Based on current evidence, we recommend limiting fusions to the medial and middle columns.

UTILITY OF BONE SCAN FOR LATE TREATMENT

No studies exist that specifically address the ideal diagnostic modalities for determining the extent of arthrodesis. In addition to plain radiographs, Level IV evidence alone supports the use of nuclear bone scans and selective anesthetic injections. Komenda and Myerson17 did not find bone scan to be useful because it tended to show uptake in areas that were painless. They did not recommend any additional imaging studies, given that clinical examination and plain radiographs were useful in determining which joints should be fused. However, Mann and Sobel21 used a bone scan to determine the extent of arthrodesis in 8 of 40 patients in their series. The majority of patients in this latter series, however, were treated for idiopathic osteoarthritis and not post-traumatic deformity.

After diagnosis with either weight-bearing radiographs or fluoroscopic stress manipulation of the foot, anatomic restoration of the tarsometatarsal joint complex should be obtained either by closed or open means. If closed, percutaneous screw fixation is an acceptable method of restoring joint alignment, and open reduction with either fixation or primary arthrodesis used where comminution or failure to obtain an anatomic reduction is noted. The dilemma remains with respect to primary arthrodesis. If comminuted, this is the procedure of choice, but it is technically difficult to perform because of lack of joint congruity and bone support. Based on Ly and Coetzee’s8 work, primary arthrodesis should, however, be part of the current treatment regimen used by orthopedic surgeons in the management of tarsometatarsal joint injury. Table 77-1 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment for injury to the tarsometatarsal joint complex.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Myerson MS, Fisher RT, Burgess AR, Kenzora JE. Fracture dislocations of the tarsometatarsal joints: End results correlated with pathology and treatment. Foot Ankle. 1986;6:225-242.

2 Hardcastle P. Injury to tarsometatarsal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64-B:349-356.

3 Buzzard BM, Briggs PJ. Surgical management of acute tarsometatarsal dislocation in the adult. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;353:125-133.

4 Aitken AP, Poulson D. Dislocations of the tarsometatarsal joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 1963;45-A:246-260.

5 Wilppula E. Tarsometatarsal fracture-dislocation. Late results in 26 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1973;44:335-345.

6 Hardcastle PH, Reschauer R, Kutscha-Lissberg E, Schoffmann W. Injuries to the tarsometatarsal joint. Incidence, classification, and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64-B:349-356.

7 Arntz CT, Veith RG, Hansen ST. Fractures and fracture-dislocations of the tarsometatarsal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:173-181.

8 Ly TV, Coetzee JC. Treatment of primarily ligamentous tarsometatarsal joint injuries: Primary Arthrodesis compared with open reduction and internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88-A:514-520.

9 Mulier T, Reynders P, Dereymaeker G, Broos P. Severe tarsometatarsal injuries: Primary arthrodesis or ORIF? Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:902-905.

10 Goosens M, DeStoop N. Tarsometatarsal’s fracture dislocation: Etiology, readiology, and results of treatment. Clin Orthop. 1983;176:154-162.

11 Willpula E. Tarsometatarsal fracture-dislocation. Acta Orthop Scand. 1973;44:335-345.

12 Myerson M. The diagnosis and treatment of injuries of the tarsometatarsal joint complex. Orthop Clin North Am. 1989;20:655-664.

13 Wilson DW. Injuries of the tarso-metatarsal joints: Etiology, classification and results of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1972;54:677-686.

14 Kuo RS, Tejwani NC, DiGiovanni CW, et al. Outcome after open reduction and internal fixation of tarsometatarsal joint injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82-A:1609-1618.

15 Myerson MS, Fisher RT, Burgess AR, et al. Fracture dislocations of the tarsometatarsal joints: End results correlated with pathology and treatment. Foot Ankle. 1986;6:225-242.

16 Ozononian T, Shereff M. In vitro determinant of midfoot motion. Foot Ankle Int. 1989;10:140-146.

17 Komenda GA, Myerson MS, Biddinger KR. Results of arthrodesis of the tarsometatarsal joints after traumatic injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1665-1676.

18 Granberry W, Lipscomb P. Dislocation of the tarsometatarsal joints. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1962;114:467-469.

19 Sangeorzan BJ, Veith RG, Hansen STJr. Salvage of tarsometatarsal joint by arthrodesis. Foot Ankle. 1990:193-200.

20 Raikin SM, Schon LC. Arthodesis of the fourth and fifth metatarsal joints of the midfoot. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:584-590.

21 Mann RA, Prieskorn D, Sobel M. Mid-tarsal and tarsometatarsal arthrodesis for primary degenerative osteoarthrosis or osteoarthrosis after trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1376-1385.