Chapter 36 What Is the Best Treatment for Idiopathic Clubfoot?

The best treatment for idiopathic clubfoot is the simplest, safest, least expensive, and most rapid method to correct the clubfoot deformity, maintain correction, and allow lifelong normal foot function. Clearly, several potential questions need to be addressed. For example, the treatment that most rapidly corrects deformity may result in painful feet long term. The safest technique for initial correction may be less effective than other techniques. Clarifying the questions to be answered is critical to evaluating the quality of evidence available.

Few investigations of “high-level” evidence address these questions. There are several reasons for this. First, true randomized studies of very different treatment methods have not been performed and will not be performed for ethical reasons. No orthopedic surgeons are agnostic with respect to the best treatment for clubfoot. Minor variations within a treatment approach are much more likely to be randomized. Second, the severity of clubfeet appears to vary in ways that are difficult to quantitate. This inability to classify feet results in stratification of individuals within a cohort of clubfoot patients who are treated in different ways based on nonquantifiable distinctions of their treating physicians, resulting in selection bias for a particular treatment. One practitioner’s “mild” deformity may be another practitioner’s “moderate” deformity. If these practitioners choose treatment with manipulation or posteromedial release (PMR) based on the “severity” of deformity, the results of their treatment regimens will not be comparable. Rating scales of severity at birth have not been shown to identify difficulty with initial correction, maintenance of correction, or long-term function for different treatment techniques. That a particular scale can predict success with a particular treatment technique has been shown, but this result cannot be generalized a priori to other techniques.1 When a technique, such as the Ponseti method, results in near-universal early correction, there is no value of rating scales for predicting the likelihood of initial deformity correction. A useful rating scale would need to predict recurrence risk or long-term outcome. No such rating scale exists. Therefore, we do not have a common starting point for comparing treatment techniques that is validated, and there may never be one. This is particularly important because many case series are a mixture of techniques based on the treating physician’s view of the severity of the deformity. Thus, many case series describe a treatment given to a selected group of patients with clubfoot from a cohort that is not defined. Third, recurrence of deformity, as opposed to failure of complete correction, is ill-defined. Generally, recurrence is in the eye of the beholding physician. Proxy measures, such as repeat surgery or need for further casting, are crude measures of recurrence. Fourth, outcome studies of sufficient length and quality to answer the question “What treatment method gives the best lifelong foot function?” are rare. A true comparative study of different methods that met Level I or II standards would require funding and commitment at a level that such studies have not and may never be performed. One confounding factor that occurs commonly in all surgical fields is that the surgical procedure is constantly “tweaked” so that long-term studies are rarely strictly comparable with the present “best” surgical treatment.

The data used to attempt to answer the questions come from an Embase and Medline search for Level I and II evidence studies written in the English language from 1950 to 2007. Almost no relevant studies were found. Using the same research strategy from 2000 to 2007, a few Level III evidence studies and several Level II studies, not initially identified, were found. Because of the paucity of information, the same databases were searched for Level IV evidence studies from 2000 to 2007, of which there were 77 identified. These case series studies were supplemented with earlier case series studies that the author believes were most informative. The analysis does not meet the standard of a systematic review. The quantity of case series studies before 2000 and in non–English language publications that would need to be surveyed for a systematic review was beyond the scope of this project but may be a worthwhile undertaking. I will attempt to give an accurate appraisal of the quality of evidence, but it should be noted that the quality of evidence is not what would be desired or expected for such a relatively common disorder.

WHAT TREATMENT BEST OBTAINS INITIAL CORRECTION IN IDIOPATHIC CLUBFOOT?

Sud and colleagues2 compared rates of initial correction and relapse comparing the Ponseti and Kite methods in a prospective, randomized study with outcome assessment by a surgeon who was blinded to the treatment. The clinic in which the children were treated had used the Kite method for 15 years and the Ponseti method for 1 year before beginning the study. Fifty-three patients with 81 feet were enrolled, and 8 were lost to follow-up and excluded from analysis. Thirty-six feet treated by the Ponseti method and 31 feet treated by the Kite method were followed for an average of 26 months. The Ponseti method had a 91.7% initial correction rate compared with 66.7% by the Kite technique. Ponseti method feet had a 21.1% relapse rate over the course of the study compared with a 38.1% relapse rate for the Kite method. The mean number of casts was statistically significantly less for the Ponseti method (6.2, Ponseti method; 10.7, Kite method), and the mean time to correction was significantly shorter for the Ponseti method (49.2 days, Ponseti method; 91.2 days, Kite method).

Three other studies address the question of early correction by comparing different methods. Herzenberg, Radler, and Bor3 in Maryland and Israel compared their first 27 patients treated by the Ponseti method with 27 patients matched from their database who had been treated by a variety of manipulative techniques by the authors or referring physicians. Their major outcome variable was need for PMR in the first year of life because of failure to correct the deformity. Only 1 foot required PMR (97%) correction with the Ponseti technique compared with only 2 feet corrected without PMR in the historical control group, which had a 6% success rate. Segev and coworkers4 compared 61 clubfeet treated by a modification of the Kite and Lovell method and managed an average of 55 months with their initial 48 feet treated with the Ponseti method that were managed for an average of 29 months with a 16-month minimum. The feet treated by the Kite and Lovell method required surgical correction in 56% of the feet. Of the feet treated by the Ponseti method, 3 (6%) required surgical correction.

Aurell and researchers5 in Sweden report a center randomized study of clubfeet treated by 2 different techniques. A consecutive series of children with clubfoot was treated by the Ponseti method at 1 hospital (9 feet) and by the Copenhagen method at another hospital (19 feet). The Copenhagen method involves manipulation by a physiotherapist 4 to 5 times per week with correction maintained by a plexidur splint for 1 month, followed by 1 or 2 times per week manipulation in the second week. At 2 months of age, a pediatric orthopedic surgeon decided whether further treatment was needed. All 9 feet treated by the Ponseti technique required only a percutaneous TAL. Of the 19 feet treated by the Copenhagen method, 12 required PMR (63%) and 1 required a posterior release (5%).

Many case series studies address the effectiveness of the Ponseti method for early correction. Changulani and researchers6 report their initial experience in the United Kingdom using the Ponseti method in 100 feet in 66 children. Ninety-six of 100 feet were fully corrected with 85 requiring percutaneous tenotomy. Colburn and Williams7 report complete initial correction of 54 of 57 feet (95%) of the first babies they treated by Ponseti method in San Francisco. Goksan and coauthors8 report on 134 feet with 97% follow-up to mean age of 46 months with a minimum of 2 years after initial casting in Turkey. Only 4 patients required PMR. Lehman and colleagues9 in New York reported successful correction in 92% of the first 45 feet treated by the Ponseti method. Tindall and coworkers10 report initial correction of 98 of 100 in Malawi by nonphysician orthopedic paraprofessionals. Shack and Eastwood11 report initial correction of 39 of 40 children in a physiotherapist-delivered Ponseti program in the United Kingdom. Morcuende and colleagues12 report initial correction in 98% of 256 feet treated by Dr. Ponseti and others at the University of Iowa.

A number of case series reports have been published of the French or Montpellier method of physiotherapy correction of clubfoot. Physiotherapy was developed and refined by Masse, Bensehal, Dimeglio, Metaizeau, and others. The technique has been published in English, but several case series in French are not included here. Dimeglio reported on three groups of feet during the evolution of the treatment in 1996. The best group consisted of 52 clubfeet. Forty percent were corrected without surgery; 35% required PMR or PMRL; and 25% required posterior release. Van Campenhout and investigators13 evaluated their results of physiotherapy and continuous passive motion machine in 64 babies with 100 feet. The authors included only infants presenting at younger than 3 months whose family strictly adhered to the protocol. With a minimum follow-up of 18 months and a mean follow-up of 3.2 years, 75 (75%) of the feet required surgery. Richards and coauthors14 report on 142 feet in 98 babies treated by the French method.14 With an average follow-up of 35 months, 20% required PMR and 29% required posterior release. Souchet and colleagues15 report what appears to be a largely personal series of Bensahel of 350 clubfeet followed to skeletal maturity. Twenty-three percent required surgical treatment at a mean age of 1 year. Stromqvist and coworkers16 report on 75 feet treated by a strict physiotherapy and bracing regimen, and managed for an average of 8 years. Sixty-seven (89%) of the feet underwent posterior release (PR) (two thirds) or PMR (one third) between 2 and 5 months of age.16 Twenty-five feet (33%) required a second operation at a mean of 4 years, and 4 feet had a third operation.

WHAT TREATMENT BEST MAINTAINS CORRECTION?

Relapse of deformity that requires treatment in clubfoot is in the “eye of the beholder.” No technical cutoff exists to say when a correction is inadequate versus when a recurrence of deformity has developed. Therefore, relapse rates are likely to vary between different investigators. Nonoperatively treated clubfeet that lose correction will relapse into a clubfoot deformity with varying amounts of recurrent equinus, varus, adductus, and cavus. Operatively treated feet may relapse in a similar way but may also lose correction into foot positions such as severe planovalgus, severe cavus from dorsal dislocation of the navicular, dorsal bunion development, and any combination of relapse and overcorrection of the initial deformities. In general, recurrent deformity requiring further treatment is reported to compromise results. One long-term report of the Ponseti method suggests that relapse of a certain type, at a certain age, can be managed in a way (anterior tibial tendon transfer to the third cuneiform) that does not compromise long-term foot function.17 Nonetheless, most relapses in corrected clubfoot treated nonoperatively occur in the first 5 years of life. The surgical literature, which is largely short- to medium-term follow-up studies (2–8 years), also suggests that recurrent deformity or overcorrection tends to occur during the rapid growing period of the foot.

A number of Level III evidence studies comparing different surgical treatment techniques demonstrate the problem of markedly different follow-up periods between different techniques that were utilized at various times at single institutions.

Tschopp and colleagues reported on 18 feet treated by PMR managed for an average of 98 months and compared them with 17 feet undergoing complete subtalar release with an average follow-up of 39 months.18 Four feet needed further surgery in the PMR group, and one foot needed further surgery in the subtalar release group.

Centel and investigators19 compared 17 feet treated by PMR and managed for 5 years with 46 feet treated by subtalar release and managed for 2 years. The PMR group had a 19% reoperation rate, and the subtalar release group had an 11% reoperation rate. Centel and investigators19 also reported on 20 patients who presented with only residual equinus who were treated by posterior release alone and who were managed for 4 years and had a 29% reoperation rate.

Nimityongskul and researchers20 compared 16 feet treated by Turco PMR and managed for an average of 8.5 years with 12 feet treated by McKay/Simons circumferential release managed for less than 4 years on average. Six of 16 PMR feet (37.5%) required further surgery, whereas no complete subtalar release feet needed further surgery during this short follow-up. The authors’ anticipated 55% of the PMR group and 17% of the complete subtalar release group would require further surgery.

Pavlovcic and Pecak21 compared the results of posterior release in 96 feet (chosen for this treatment because of mild deformity) with PMR in 75 feet (chosen for this treatment because of severe deformity). Both groups were managed for slightly more than 12 years on average. Sixty-eight percent of the PR feet required further surgery, and 42% of the PMR feet underwent further surgery.

A single study compared 30 feet treated by PMR with 30 feet treated by PMR and an anterior tibial tendon lengthening.22 Follow-up was 11 and 9 years for the respective groups. Eight of 30 (27%) of the PMR-treated feet, and 2 of 30 (7%) of the feet with PMR plus anterior tibial tendon lengthening required further surgery. Seventeen percent of all feet required further surgery.

Simons23 report on 21 feet treated by PMR and lateral release with 25 feet treated with a complete subtalar release. A short follow-up of 3 years revealed that 4 feet (9% of the entire group) required further surgery. Two feet had PMR and 2 had complete subtalar release. Furthermore, Simons23 describe, major complications that may require further surgery in an additional 24 patients (52%).

Otremski and coworkers24 compared 30 feet treated by PMR with an 8– to 14– year follow-up with 22 feet treated by a modified PMR with a 5-year average follow-up period. Five patients treated by PMR and 1 patient treated by modified PMR had further surgery at last follow-up examination (12% of the entire group).

Thompson and colleagues24a fashioned three groups from a population of 244 clubfeet of which 73% were managed for less than 10 years and 27% had longer than a 10-year follow-up period. The group treated with a limited or á la carte release (112 feet) required further surgery in 74% of feet and recasting in 8%. A second group was defined as having had a failed incomplete release and had undergone a complete PMR (39 feet). Ten percent of this group had subsequent surgery, and 28% were recasted. A group of 93 feet treated primarily by PMR had a 9% reoperation rate and an 11% recasting rate.

Case series studies with short-term results that shed light on recurrence rates are common but are subject to all the biases inherent in such studies. Fourteen representative studies are summarized with respect to recurrence of deformity requiring surgical treatment. Surgical treatment in these 14 reports were variously described as “Turco procedure,” “modified Turco,” “soft tissue release,” “selected soft tissue release,” “a la carte,” “complete subtalar release,” “Simon release,” “McKay release,” “early posterior release,” “Goldner release,” and “staged plantar medial followed by postero lateral release.” Follow-up ranged from 2 to 16 years with an average follow-up period of 8 years. Number of feet reported ranged from 16 to 271 with an average of 91 feet. Further surgery rates ranged from 0% to 68% with an average of 24%. These articles are by no means exhaustive of the case series published on short-term results of clubfoot, but they are representative of the English language articles including the work of Turco and McKay.25–38

Relapse in the Ponseti method requires a somewhat different assessment. Few Ponseti method–treated feet undergo surgery at an early age (excluding percutaneous tenotomy), and relapses are treated by repeat manipulation and casting until the child is mature enough for an anterior tibial tendon transfer to the third cuneiform to be performed. Morcuende and colleagues12 reviewed 256 feet treated at the University of Iowa between 1991 and 2001 with an average follow-up of 26 months (6–96 months). Seventeen patients suffered a relapse (11% of feet). Four feet (2.5%) required PR or PMR, and four feet required anterior tibial transfer to the third cuneiform. The authors found that 2 of 140 patients (∼1%) whose parents reported compliance with the bracing regimen relapsed, whereas 15 of 17 patients whose parents were not compliant relapsed (89%).

Dobbs and researchers39 evaluated recurrence risk in 51 consecutive infants with 86 idiopathic clubfeet managed for an average of 27 months (24–35 months). They report complete initial correction. Twenty-seven feet relapsed, and all relapses were treated successfully by manipulation and recasting. All of the relapsed feet occurred in families who were noncompliant with brace wear. Compliance was related to relapse with an odds ratio of 183 (P < 0.00001).

Haft and coworkers40 report on 73 feet in 51 infants treated in New Zealand with a mean follow-up period of 35 months (24–65 months). They report a 41% relapse rate with only 51% brace compliance. Relapses were minor in 18% of patients and required only TAL or anterior tibial tendon transfer, or both. Relapses were major in 24% of patients and required PR or PMR. Noncompliance with brace treatment conferred a five times increased risk for relapse.

WHAT TREATMENT GIVES BEST LONG-TERM FOOT FUNCTION?

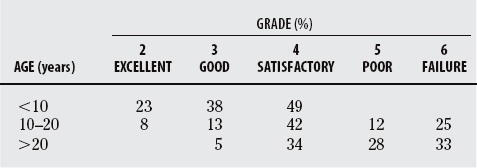

Multiple reports of “long-term” follow-up of clubfoot exist. Few of these studies report on a cohort whose members are all skeletally mature much less middle aged or elderly and, therefore, can scarcely be called long term. The mean life span in most of the developed world is the late 70s. These studies are only long term from the perspective of an orthopedic surgeon’s career, which is not an appropriate determinant of length of follow-up. Data from long-term follow-up studies of Legg–Calve–Perthes disease should be cautionary. Most patients responded well until the middle of the sixth decade of life, at which time disabling arthritis requiring THR became common. “Good” functional results in the teens, 20s, 30s, and so on cannot be extrapolated without data. For example, Krauspe and colleagues41 used the McKay rating system (a nonvalidated, multidomain, idiosyncratic measuring scheme) to assess the outcomes of 104 feet in 64 patients treated by the Scheel technique (a PR with PMR as needed with a traction suture on the calcaneus). The results deteriorated markedly from less than 10 to 10 to 20 years to greater than 20 years (Table 36-1).

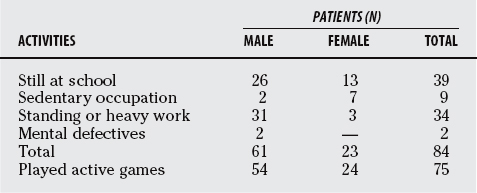

Long-term results of clubfoot treatment are generally a confused mix of ages, procedures, and evaluations. A classic and typical report is the 1964 report by Wynne-Davies.42 She reports on 84 patients with 121 feet (88% follow up) who had completed treatment. Completion of treatment was arbitrarily defined as older than 10 years. Ninety-three feet belonged to patients 10 to 21 years of age, and 28 feet belonged to patients 22 to 35 years of age. Twenty-eight feet had closed treatment only; 51 feet had PMR, anterior tendon transfer laterally, or both; and 24 feet had arthrodesis, of which 10 had had a prior soft-tissue procedure. Patient-centered outcomes consisted of the following copied directly from the article:

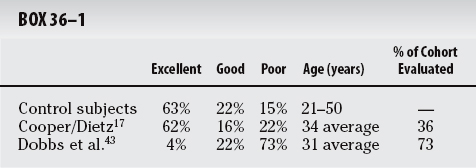

Only one investigation has been published that reports outcomes in skeletally mature clubfoot patients evaluated by a validated outcomes instrument. Dobbs and coworkers43 report on 73 feet in 45 patients treated by posterior and plantar release in 13 feet (average follow-up, 31 years; range, 30–32 years) and Turco-type PMR in 60 feet (average follow-up, 28 years; range, 25–29 years). They were able to find 73% of eligible patients. Using the health survey Short Form-36 (SF-36) for evaluation of health-related quality of life, this cohort scored nearly 2 standard deviations less than the average on the physical functioning scale and average on the mental functioning scale. No study has been reported with which to compare this validated outcome result, but the physical functioning level was similar to cohorts of patients with chronic heart failure, awaiting coronary bypass surgery, and suffering cervical radiculopathy. The authors of this study used other outcome measures as well that, although not validated, have been used in other long-term follow-up studies of patients with clubfoot.

Cooper and Dietz17 reviewed 45 patients with 71 clubfeet who were treated under the supervision of Dr. Ponseti at an average age of 34 years (range, 25–42 years). Only 36% of the eligible cohort was evaluated. The authors of this study administered a questionnaire to a control group of 97 patients of similar age (21–50 years old) and sex to the clubfoot cohort who were screened only for the absence of a congenital foot abnormality. The questionnaire began as follows:

The outcome as defined earlier was not different between the control and Ponseti-treated patients with clubfoot. Dobbs and coworkers43 administered these questions and compared them with quite different results (Box 36-1).

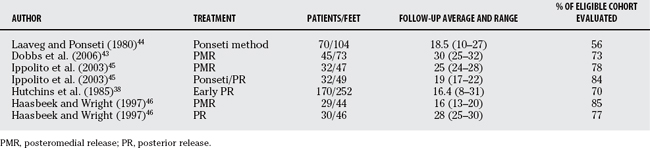

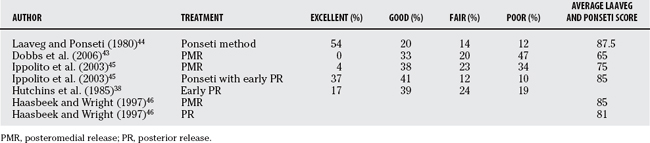

Several studies have used the Laaveg and Ponseti functional rating system for clubfoot as their only or 1 of several outcome measures. This rating scheme is not validated but combines reasonable elements of outcomes that are arbitrarily weighted and scored. Excellent was defined as 90 to 100 points, good as 80 to 89, fair as 70 to 79, and poor as less than 70. The rating scheme is presented in Table 36-3. Tables 36-4 and 36-5 summarize long-term follow-up articles.

| CATEGORY | POINTS |

|---|---|

| Satisfaction (20 points) | |

| I am | |

| a. very satisfied with the end result | 20 |

| b. satisfied with the end result | 16 |

| c. neither satisfied nor unsatisfied with the end result | 12 |

| d. unsatisfied with the end result | 8 |

| e. very unsatisfied with the end result | 4 |

| Function (20 points) | |

| In my daily living, my clubfoot | |

| a. does not limit my activities | 20 |

| b. occasionally limits my strenuous activities | 16 |

| c. usually limits me in strenuous activities | 12 |

| d. limits me occasionally in routine activities | 8 |

| e. limits me in walking | 4 |

| Pain (30 points) | |

| My clubfoot | |

| a. is never painful | 30 |

| b. occasionally causes mild pain during strenuous activities | 24 |

| c. usually is painful after strenuous activities only | 18 |

| d. is occasionally painful during routine activities | 12 |

| e. is painful during walking | 6 |

| Position of heel when standing (10 points) | |

| Heel varus, 0 degrees or some heel valgus | 10 |

| Heel varus, 1–5 degrees | 5 |

| Heel varus, 6–10 degrees | 3 |

| Heel varus, greater than 10 degrees | 0 |

| Passive motion (10 points) | |

| Dorsiflexion | 1 point per 5 degrees (up to 5 points) |

| Total varus-valgus motion of heel | 1 point per 10 degrees (up to 3 points) |

| Total anterior inversion-eversion of foot | 1 point per 25 degrees (up to 2 points) |

| Gait (10 points) | |

| Normal | 6 |

| Can toe-walk | 2 |

| Can heel-walk | 2 |

| Limp | −2 |

| No heel-strike | −2 |

| Abnormal toe-off | −2 |

Ippolito and researchers’45 PMR cohort scored statistically significantly more poorly on the Laaveg and Ponseti scale than did their Ponseti with PR cohort. A detail that may be important is that Ippolito’s PR was an ankle capsulotomy alone. Most of the other descriptions of PR that are reported here (Hutchins et al38 and Haasbeek and Wright46) include a posterior subtalar joint and ligament release as well. The devil may be in the details—the more joints opened, the worse the results. In contrast, there was no significant difference between Haasbeek and Wright’s PMR and PR group. Haasbeek and Wright’s PMR group had significant numbers of skeletally immature subjects, as did Hutchins’s group and Laaveg and Ponseti’s group.

Summary

It is difficult to extrapolate firm conclusions from such a limited number of long-term follow-up studies. What available evidence suggests is that joint release surgery and Ponseti treatment give comparable results when evaluating patients whose average age is in the teenage years and the evaluation instrument is the Laaveg and Ponseti scale. The only 2 studies that compare patients who are all skeletally mature with average ages in the 30s strongly support the superiority of the Ponseti method over surgical release. Nonetheless, these are only 2 articles. The weight of evidence suggests that long-term results are better the fewer joints are surgically invaded, but the stren-gth of the evidence is poor.

CONCLUSIONS

The long-term evidence is extremely thin but supports Ponseti method over joint release surgery for the correction of clubfoot. Table 36-6 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Bensahel H, Csukonyi Z, Desgrippes Y, Chaumien JP. Surgery in residual clubfoot: One-stage medioposterior release “a la carte.”. J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7:145-148.

2 Sud A, Tiwari A, Sharma D, Kapoor S. Ponseti’s vs. Kite’s Method in the Treatment of Clubfoot: A Prospective Randomized Study. International Orthopaedics (SICOT). 2007;32:15-21.

3 Herzenberg JE, Radler C, Bor N. Ponseti versus traditional methods of casting for idiopathic clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:517-521.

4 Segev E, Keret D, Lokiec F, et al. Early experience with Ponseti method for the treatment of congenital idiopathic clubfoot. Israel Medical Assoc J. 2005;7:307-310.

5 Aurell Y, Andriesse H, Johansson A, Jonsson K. Ultrasound assessment of early clubfoot treatment: A comparison of the Ponseti method and a modified Copenhagen method. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:347-357.

6 Changulani M, Garg NK, Rajagopal Ts, et al. Treatment of idiopathic clubfoot using the Ponseti method. Initial experience. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1385-1387.

7 Colburn M, Williams M. Evaluation of the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot by using the Ponseti method. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2003;42:259-267.

8 Goksan SB, Bursali A, Bilgili F, et al. Ponseti technique for the correction of idiopathic clubfeet presenting up to 1 year of age. A preliminary study in children with untreated or complex deformities. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2006;126:15-21.

9 Lehman WB, Mohaideen A, Madan S, et al. A method for the early evaluation of the Ponseti (Iowa) technique for the treatment of idiopathic clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003;12:133-140.

10 Tindall AJ, Steinlechner CWB, Lavy CBD, et al. Results of manipulation of idiopathic clubfoot deformity in Malawi by orthopaedic clinical officers using the Ponseti method: A realistic alternative for the developing world? J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:627-629.

11 Shack N, Eastwood DM. Early results of a physiotherapist-delivered Ponseti service for the management of idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus foot deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1085-1089.

12 Morcuende JA, Dolan LA, Dietz FR, Ponseti IV. Radical reduction in the rate of extensive corrective surgery for clubfoot using the Ponseti method. Pediatrics. 2004;113:376-380.

13 Van Campenhout A, Molenaers G, Moens P, Fabry G. Does functional treatment of idiopathic clubfoot reduce the indication for surgery? Call for a widely accepted rating system. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10:315-318.

14 Richards BS, Johnston CE, Wilson H. Nonoperative clubfoot treatment using the French physical therapy method. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:98-102.

15 Souchet P, Bensahel H, Themar-Noel C, et al. Functional treatment of clubfoot: A new series of 350 idiopathic clubfeet with long-term followup. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2004;13:189-196.

16 Stromqvist B, Johnsson R, Jonsson K, Sunden G. Early intensive treatment of clubfoot: 75 feet followed for 6-11 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:183-188.

17 Cooper DM, Dietz FR. Treatment of idiopathic clubfoot: A thirty-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1477-1489.

18 Tschopp O, Rombouts JJ, Rossillon R. Comparison of posteromedial and subtalar release in surgical treatment of resistant clubfoot. Orthopedics. 2002;25:527-529.

19 Centel T, Bagatur AE, Out T, Aksu T. Comparison of the soft-tissue methods in idiopathic clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:648-651.

20 Nimityongskul P, Anderson LD, Herbert DE. Surgical treatment of clubfoot: A comparison of two techniques. Foot Ankle. 1992;13:116-124.

21 Pavlovcic V, Pecak F. Surgical treatment of clubfoot: The significance of talocalcaneonavicular malposition correction. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8:1-4.

22 Wicart PR, Barthes X, Ghanem I, Seringe R. Clubfoot posteromedial release: Advantages of tibialis anterior tendon lengthening. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:526-532.

23 Simons GW. Complete subtalar release in club feet: Part II—Comparison with less extensive procedures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67:1056-1065.

24 Otremski I, Salama R, Khermosh O, Wientroub S. An analysis of the results of a modified one-stage posteromedial release (Turco Operation) for the treatment of clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7:149-151.

24a Thompson GH, Richardson AB, Westin WW. Surgical management of resistant congenital talipes equinovarus deformities. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:652-665.

25 Turko VJ. Resistant congenital club foot—one stage posteromedial release with internal fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:805-813.

26 McKay DW. New concept of and approach to clubfoot treatment: Section III—evaluation and results. J Pediatr Orthop. 1983;3:141-148.

27 Moses W, Allen BLJr, Pugh LI, Stasikelis PJ. Predictive value of intraoperative clubfoot radiographs on revision rates. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:529-532.

28 Lau JHK, Meyer LC, Lau HC. Results of surgical treatment of talipes equinovarus congenital. Clin Orthop. 1989;248:219-226.

29 Levin MN, Kuo KN, Harris GF, Matesi DV. Posteromedial release for idiopathic talipes equinovarus. Clin Orthop. 1989;242:265-268.

30 Yngve DA, Gross RH, Sullivan JA. Clubfoot release without wide subtalar release. J Pediatr Orthop. 1990;20:473-476.

31 Blakeslee TJ, DeValentine SJ. Management of the resistant idiopathic clubfoot: The Kaiser experience from 1980-1990. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1995;34:167-176.

32 Esser RD. The medial sagittal approach in the treatment of the congenital clubfoot. Clin Orthop. 1994;302:156-163.

33 Dewaele J, Zachee B, De Vleeschauwer P, Fabry G. Treatment of the idiopathic clubfoot: Critical evaluation of different types of treatment programs. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1994;3:89-95.

34 Templeton PA, Flowers MJ, Latz KH, et al. Factors predicting the outcome of the primary clubfoot surgery. Can J Surg. 2006;49:123-127.

35 Uglow MG, Clarke NM. The functional outcome of staged surgery for the correction of talipes equinovarus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:517-523.

36 Singh BI, Vaishnavi AJ. Modified Turco procedure for treatment of idiopathic clubfoot. Clin Orthop. 2005;438:209-214.

37 Sobel E, Giorgini RJ, Michel R, Cohen SI. The natural history and longitudinal study of the surgically corrected clubfoot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2000;39:305-320.

38 Hutchins PM, Foster BK, Paterson DC, Cole EA. Long-term results of early surgical release in club feet. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:791-798.

39 Dobbs MB, Rudzki JR, Purcell DB, et al. Factors predictive of outcome after use of the Ponseti method for the treatment of idiopathic clubfeet. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:22-27.

40 Haft GF, Walker CG, Crawford HA. Early clubfoot recurrence after use of the Ponseti method in a New Zealand population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:487-493.

41 Krauspe R, Vispo Seara JL, Lohr JF. Long-term results after surgery for congenital clubfoot. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1996;2:77-82.

42 Wynne-Davies R. Talipes Equinovarus—a review of eighty-four cases after completion of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1964;46:464-476.

43 Dobbs MB, Nunley R, Schoenecker PL. Long-term follow-up of patients with clubfeet treated with extensive soft-tissue release. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:986-996.

44 Laaveg SJ, Ponseti IV. Long-term results of treatment of congenital clubfoot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:23-30.

45 Ippolito E, Farsetti P, Caterini R, Tudisco C. Long-term comparative results in patients with congenital clubfoot treated with two different protocols. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1286-1294.

46 Haasbeek JF, Wright JG. A comparison of the long-term results of posterior and comprehensive release in the treatment of clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:29-35.