Chapter 72 What Is the Best Treatment for End-Stage Hallux Rigidus?

Hallux rigidus is the commonest form of osteoarthritis in the foot with an incidence of 1 in 40 adults older than 50 years, and it is the second commonest complaint of the great toe behind hallux valgus.1–3

Radiographic evaluation reveals findings consistent with osteoarthritis, which includes joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation (particularly dorsally), subchondral cysts, and sclerosis. Hattrup and Johnson4 developed a radiographic classification of hallux rigidus, which was divided into three grades. In grade I, mild-to-moderate osteophytes are present; however, there is preservation of the joint space. In grade II, there is moderate osteophyte formation with narrowing of the joint space and subchondral sclerosis. Grade III is characterized by marked osteophyte formation, loss of the joint space, and subchondral cysts may be present.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

Noncomparative Studies (Case Series; Level IV)

Cheilectomy.

A cheilectomy entails excision of the dorsal osteophyte together with a portion of the dorsal degenerative articular surface. It is recommended to remove up to a third of the articular surface with the goal to obtain a minimum of 70 degrees of dorsiflexion. Usually included with the procedure is the resection of any dorsal osteophytes off the proximal phalanx, debridement of the joint, loose body removal, and synovectomy.5,6

Cheilectomy has been shown to have good results in early stages of hallux rigidus.4,7 Some authors have reported good clinical results for cheilectomy irrespective of radiographic grade.4–6 No study exists that isolates the subset of patients with advanced hallux rigidus. The largest published series is reported by Coughlin and Shurnas7 where 93 feet of all stages of hallux rigidus underwent a cheilectomy and were reviewed retrospectively, with an average follow-up period of 9.6 years. Of the nine feet that had end-stage radiographic changes, five did not respond to treatment and underwent arthrodesis at a mean of 6.9 years after cheilectomy.7 Easley and coworkers8 conducted a retrospective review of 68 feet of all stages treated with cheilectomy at an average follow-up period of 5 years. A 90% satisfaction rate was achieved in the entire group. Of the nine feet that remained symptomatic; eight of those had end-stage grade 3 changes. It was noted that all nine demonstrated pain at the midrange of the motion arc, which would be suggestive of more global and advanced degenerative changes in the hallux MTP joint. The authors conclude that this was a negative prognosticator after cheilectomy.8 Based on these two Level IV studies, a cheilectomy cannot be recommended for treatment of end-stage hallux rigidus (grade C level of recommendation).

Keller Resection Arthroplasty.

In 1904, Keller described a procedure that involved excision of a portion of the proximal phalanx of the hallux for the treatment of hallux valgus and associated osteoarthritis of the first MTP joint. Although this procedure decompresses the joint, excessive resection can lead to instability secondary to loss of both bone and soft-tissue restraints. Shortening of the great toe occurs, and the plantar aponeurosis is disrupted, which impairs the windlass mechanism contributing to the decreased stability of the medial column. Commonly described complications include transfer metatarsalgia, weak push off, and a cock-up deformity of the toe, which has led many investigators to recommend this procedure for low-demand and older patients.9,10

When reviewing the results of the Keller arthroplasty, variable outcomes are found with few being prospective or comparative trials. No studies review the subset of younger or higher demand patients. In addition, many studies also include hallux valgus deformities and lack any uniformity on grading or outcome measures, particularly older studies. Love and coworkers10 performed a prospective trial studying 75 feet in patients with hallux valgus and hallux rigidus. Inclusion criteria included age older than 50 years, symptomatic osteoarthritis of the first MTP joint, and relatively low demand as defined by occupation and lifestyle. No differentiation was reported in radiographic grade of the osteoarthritis present in the first MTP joint. Mean follow-up period was 31 months. The authors report that joint pain was alleviated in 40 of 44 patients with an overall satisfaction rate of 77%. No increased incidence of postoperative metatarsal callosities occurred. However, they report a cock-up deformity after surgery in 28 feet compared with 8 before surgery, as well as a slight decrease in first MTP joint motion after surgery.10

Biologic Interpositional Arthroplasty.

Hamilton and colleagues12 performed a retrospective review on 30 patients with advanced hallux rigidus who were treated with an EHB tendon and capsular interpositional arthroplasty collected over 10 years. However, the follow-up time is unknown. Subjectively, 93.3% of patients reported that they would undergo the same procedure. The American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) pain scores improved from 23.2 points before surgery to 37.4 points after surgery, and the average dorsiflexion improved from 10 to 50 degrees. No patients described weakness in push off or lateral metatarsalgia, and no calluses were found underneath the metatarsal heads.12 Kennedy and coworkers13 retrospectively reviewed 18 patients (21 feet) over a mean follow-up period of 38 months who underwent capsular interpositional arthroplasty utilizing the EHB tendon. Eighteen of 21 feet were grade 3 radiographically, whereas the remainder were grade 2. All 18 patients had pain relief, whereas 17 reported they would have the same procedure repeated. The mean postoperative increase in dorsiflexion was 37 degrees. One patient reported transfer metatarsalgia. The authors13 conclude that interpositional arthroplasty was indicated for treatment of advanced hallux rigidus, and the technique as described by Hamilton and colleagues12 had reproducible outcomes. However, Lau and Daniels1 used a similar technique and retrospectively reviewed a series of 11 patients with a mean follow-up period of 2 years. Ten of 11 patients were grade III radiographically, whereas the other patient was grade II. Patient satisfaction was 72.7%. However, weakness of the great toe was reported in 72.7% of patients, whereas 27.3% reported lateral metatarsalgia. The investigators conclude that interpositional arthroplasty should be considered a salvage procedure with less reliable results.1

Barca14 reports on the use of the plantaris tendon as the biologic spacer that was combined with a 20- to 30-degree dorsal wedge osteotomy of the proximal phalanx. An articulated external fixator was used to maintain the diastasis of the joint. Barca retrospectively reviewed a series of 12 patients over a period of 21 months. All patients reported good or excellent results, and dorsiflexion was improved by an average of 44 degrees. Coughlin and Shurnas15 used a gracilis tendon as a graft and retrospectively reviewed seven patients over an average of 42 months of follow-up. All seven patients rated their result as good or excellent with a mean increase in AOFAS scores from 46 to 86. Mean dorsiflexion improved from 9 to 34 degrees and all demonstrated good to excellent plantarflexion strength. Four patients did report mild metatarsalgia. The authors conclude that this technique gave excellent pain relief and reliable function of the hallux.15

Arthrodesis.

Arthrodesis of the first MTP joint has been one of the mainstays of surgical treatment of severe hallux rigidus, particularly in the younger, more active population. This procedure eliminates the painful movement of the joint and provides a stable medial column for ambulation. However, it has not been without controversy. An arthrodesis has a prolonged recovery course compared with other procedures, and there are complications such as nonunion, progressive arthrosis of the interphalangeal joint, and lateral metatarsalgia.16 The long-term success and the impact on the gait cycle have also been a concern.

Joint Preparation and Fixation Technique.

Authors have debated on the methods to prepare the joint surfaces and stabilize the arthrodesis site. There are two popular methods to prepare the fusion site. The first method is using a cone reamer system where one reamer is used to create a convex surface at the base of the proximal phalanx whereas a reciprocal reamer leads to a concave surface on the metatarsal head. The second method of planar excision is simpler, where an oscillating saw can be used to create flat cancellous surfaces on either side of the joint that are then brought together. Various fixation techniques have been described; older studies have used wire suture, K-wires, or Steinmann pins, whereas more recent authors have used a dorsal plate, interfragmentary screws, or Herbert screws. Several biomechanical studies have compared both different methods of joint preparation and fixation techniques. Curtis and researchers17 compared four fixation techniques: (1) planar excision with K-wire fixation, (2) planar excision and fixation with dorsal plate and screws, (3) planar excision and fixation with a single interfragmentary screw, and (4) cup and cone preparation and fixation with an interfragmentary screw. Their results revealed that the cup and cone group had greater stiffness and load to failure compared with all other groups. It was concluded that the cup and cone method of fusion provided the majority of the stability, whereas the method of fixation was secondary.17 Politi and coauthors18 compared the strength of five techniques of first MTP arthrodesis: (1) surface excision with a machined reaming and fixation with a 3.5-mm cortical interfragmentary lag screw, (2) surface excision with machined conical reaming and fixation with crossed K-wires, (3) surface excision with machined conical reaming and fixation with a 3.5-mm cortical lag screw and a four-hole dorsal miniplate, (4) surface excision with machined conical reaming and fixation with a four-hole dorsal miniplate and no lag screw, and (5) planar surface excision and fixation with a single oblique 3.5-mm interfragmentary cortical lag screw. The most stable technique found was the combination of the machined conical reaming and an oblique interfragmentary lag screw and dorsal plate, whereas the dorsal plate and K-wire fixation alone were the weakest.18

Clinical Outcomes.

Clinical studies have shown high success rates with fusion using a variety of techniques. Goucher and Coughlin19 prospectively evaluated 50 patients who underwent first MTP arthrodesis using dome-shaped reamers and a dorsal plate and crossed screws. Diagnoses included hallux rigidus, hallux valgus, rheumatoid arthritis, failure of prior first MTP procedures, hallux varus, and neuromuscular disorders. They achieved a 96% satisfaction rate and 92% union rate at an average of 16 months of follow-up. A significant improvement was found in AOFAS scores.19 Flavin and colleagues20 in a prospective study had similar results. Twelve first MTP arthrodeses were performed using cone reaming preparation and fixation with a dorsal plate with an average follow-up period of 18 months. Diagnoses included hallux valgus, hallux rigidus, and nonunion of a previous first MTP fusion. All patients showed evidence of radiographic union at 6 weeks and had significant increases in both AOFAS hallux and SF-36 (36-Item Short Form Health Survey) scores.20 The literature has limitations because most series include a number of preoperative diagnoses besides hallux rigidus, mainly hallux valgus.

Prosthetic Replacement Arthroplasty.

Silastic Implants.

Because of the success of silastic implants in the hand, they were adapted for the first MTP joint. This led to the development of a double-stemmed implant, which allowed the implant to act as a dynamic spacer and, as a result, maintain joint space and motion. Although clinical studies showed good clinical satisfaction, there was concern about the longevity of the prosthesis. In a prospective study, Cracchiolo and coworkers21 observed 66 patients over an average of 5.8 years. Subjectively, 83% of the patients were satisfied while the average range of motion was 42 degrees. However, radiographically, the implant did not fare as well. Osteophyte formation was present in 23 patients, and of those, 12 had nearly 50% articular space encroachment. Radiographic cysts were noted in 35% of the patients, and eight implant fractures were identified.21 The area of concern for implant failure was at the hinged portion of the prosthesis, which was subjected to high shear forces at the joint. Titanium grommets were added to protect this area and increase durability of the implants. In a retrospective review, Swanson and de Groot22 retrospectively report on 90 implants; all patients were clinically improved, and no implant fractures were identified. Sebold and Cracchiolo23 also retrospectively reviewed a series of 47 feet that received a silicone implant with titanium grommets over an average follow-up period of 51 months. Thirty of 47 patients were completely satisfied with no radiographic evidence of implant fracture, although 5 feet had radiolucencies around the implant, and subsidence was noted in 15 feet. This was compared with a similar group of patients who had been treated with hinged implants, and it was noted that 30 of 41 feet had evidence of radiolucencies around the implant with two implant fractures. It was concluded that the titanium grommets appeared to protect the silicone implant and may help improve its longevity.23 Despite the modification with titanium grommets, the use of silicone implants remains controversial, in particular, with the potential complications of silicone debris. The silicone particles can cause a foreign body reaction that leads to synovitis and potential bone erosion. Systemic effects are also a concern because silicone microfragments invade the lymphoreticular system, and the long-term complications of this process have yet to be identified.24

Metallic Implants.

With the success of the metallic hip and knee arthroplasty, similar implants were designed for the hallux. In a prospective trial, Pulavarti and colleagues25 prospectively reviewed the results of 36 Bio-Action prostheses (Osteomed, Addison, Texas) a nonconstrained, uncemented implant, with a minimum follow-up period of 3 years. Diagnoses included hallux rigidus, hallux valgus with degenerative changes, failed hallux surgery, gouty arthritis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Results showed a significant improvement in dorsiflexion, MTP arc of motion, and Hallux MTP scale after surgery. Subjective satisfaction was rated as either excellent or good in 77.5% of patients. Two patients required revision surgery (resection arthroplasty and arthrodesis) after poor outcomes; however, the authors did not identify any obvious cause for the failures. Radiographic studies did reveal periprosthetic radiolucency and subsidence in 33% of the implants, although this did not affect functional outcome.25 Fuhrmann and coauthors26 prospectively reviewed the results of 43 ReFlexion (Osteomed, Addison, Texas) MTP endoprostheses with an average follow-up period of 3 years. The ReFlexion endoprosthesis is a modular, nonconstrained, porous-coated implant that allows for either cementless or cemented fixation. Thirty-two patients had painful end-stage hallux rigidus, whereas other diagnoses included failed resection arthroplasty, cheilectomy, and silicone implants. Because of poor bone stock, cement was used in 20 phalangeal components and 5 metatarsal components. Results revealed all patients reported significant reduction in pain levels with a visual analogue scale pain. AOFAS scores and passive dorsiflexion significantly improved after surgery. However, the main area of concern was a reduction of MTP joint stability. About 28% of patients had an increased dorsoplantar drawer test, and 16% had medial instability (2+) with the toe in a slight valgus position. Radiographically, 30% of patients had mild hallux valgus deformities, 9% had slight varus deformities, and 21% showed plantar subluxation of the phalangeal component. Radiolucent lines were evident in 23% of phalangeal components (35% cemented vs. 13% cemented) and 9% of metatarsal components (equal cemented vs. uncemented percentages).26

Hemiarthroplasty.

Although hemiarthroplasties of the proximal phalanx for the treatment of hallux rigidus have been available in the past half century, they have not gained much popularity compared with other forms of surgical treatment. Correspondingly, the literature reveals few published studies on their outcomes. Advocates of metallic hemiarthroplasties believe that it avoids the high dorsal shear forces associated with arthroplasties involving the metatarsal heads and does not possess the inherent structural flaws of a silastic implant.27,28

Townley and Taranow27 performed a long retrospective review of 279 patients treated with a metallic hemiarthroplasty of the proximal phalanx with a follow-up range from 8 months to 33 years. Indications for treatment included hallux rigidus (n = 171), rheumatoid arthritis (n = 29), and varying degrees of osteoarthritis associated with hallux valgus (n = 79). The authors report good or excellent results in 95% of patients. Only two patients with hallux rigidus were unsatisfied: one was complicated by an infection, whereas the other received an oversized implant. The remainder of failures occurred in eight of the patients with hallux valgus and three with rheumatoid arthritis. Only one case of clinical or radiographic evidence of loosening was reported, which occurred in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis with poor bone quality.27 Taranow and coworkers28 retrospectively reviewed 28 patients who received metallic hemiarthroplasties for severe hallux rigidus over an average follow-up period of 33 months. Twenty-three of 28 patients were completely satisfied, 3 were satisfied with reservations, and 2 were dissatisfied. Radiographically, four implants were inserted in a dorsiflexed position, which was demonstrated on postoperative radiographs, and three of these showed evidence of subsidence and loosening. No other cases of loosening or progressive deformities were reported. Two patients demonstrated mild recurrence of osteophytes, but this did not correlate with patient satisfaction. The authors conclude that technical errors likely contributed to radiographic loosening.28 However, not all results have been positive. Kondel and Menger29 retrospectively reviewed 10 patients (13 feet) who underwent a titanium hemiarthroplasty for grade II or III hallux rigidus. Follow-up ranged from 37 to 105 months. Eleven of 13 toes had absent or mild pain. However, all implants had evidence of varying degrees of radiolucencies and subsidence. One implant was removed and underwent interpositional arthroplasty after fracture and painful nonunion.29

Comparative Studies

Keller Arthroplasty versus Arthrodesis.

O’Doherty and coauthors30 report a prospective randomized trial comparing Keller’s arthroplasty and arthrodesis of the first MTP joint for the treatment of both hallux valgus and rigidus in 110 feet with a minimum follow-up period of 2 years. The inclusion criteria were age older than 45 years, with a mean of 60.5 years. They report similar results among the two groups with a satisfactory or excellent result in 98% who underwent a Keller arthroplasty compared with 95% in the arthrodesis group. No significant difference was found between the groups in the incidence of postoperative transfer metatarsalgia or cock-up deformity. However, the incidence rate of nonunion in the arthrodesis group was extremely high at 44%. The majority of patients were asymptomatic, with only 4 of 22 requiring revision. The authors attributed this to the wire suture and K-wire fixation technique, which was a poor biomechanical construct.30

Arthrodesis versus Total Joint Replacement.

Gibson and Thomson31 performed a prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing arthrodesis versus total replacement arthroplasty for hallux rigidus. Sixty-three patients (77 feet) were randomized to either arthrodesis (22 patients, 38 toes) or a BioMet, uncemented total joint arthroplasty (27 patients, 39 toes). Patient mean age was 55 (range, 34–77) years. Arthrodesis was performed using planar excision preparation and metal cerclage wire and K-wire for fixation; all arthroplasties were uncemented. Results revealed that all 38 arthrodeses united, although 7 acquired minor wound infections and 2 required extraction of the K-wire. In contrast, 6 of 39 arthroplasties required removal because of loosening of the phalangeal components. At 2 years, final range of active joint dorsiflexion was no greater than preoperative movement. Visual analogue pain scores revealed significant reduction in both groups. However, those who had an arthrodesis improved more than those in the arthroplasty group. More patients in the arthrodesis group preferred both their function result and the appearance of their toe after arthrodesis. At 2 years, only 3% of patients in the arthrodesis group would not have undergone the same surgery again compared with 40% in the arthroplasty group. The authors conclude that outcomes after arthrodesis were better than those after arthroplasty, and arthrodesis was clearly preferred by most patients.31

Arthrodesis versus Hemiarthroplasty.

Raikin and coworkers32 retrospectively reviewed a series of patients with severe hallux rigidus who were treated with either a metallic hemiarthroplasty or an arthrodesis. Twenty-one hemiarthroplasties with a mean follow-up period of 79 months were compared with 27 arthrodeses with a mean follow-up period of 30 months. The Biopro implant (Biopro, Port Huron, Michigan) was utilized for the hemiarthroplasties, whereas the arthrodesis technique involved planar excision with two obliquely oriented screws for fixation. Results revealed that all arthrodesis went on to unite within 12 weeks, and no revisions were required. Only two patients required screw removal for prominent hardware. Of the 21 hemiarthroplasties, 5 required revision surgery (1 was revised, 4 were converted to an arthrodesis), whereas eight that had survived showed evidence of plantar cutout of the prosthetic stem. Patients who underwent arthrodesis had significantly greater satisfaction rates, greater AOFAS hallux scores, and lower visual analogue pain scores compared with the hemiarthroplasty group. The authors conclude that arthrodesis was more predictable than hemiarthroplasty for alleviating symptoms and restoring function in patients with severe hallux rigidus.32

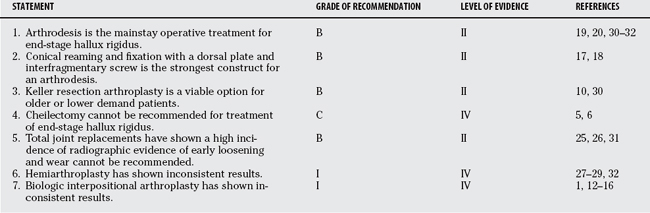

Hemiarthroplasty has shown some promise in long-term survivorship, but results overall have been variable. Biologic interpositional arthroplasty has not shown consistent, reliable results. There is insufficient evidence to allow for a recommendation for or against this treatment of end-stage hallux rigidus. Table 72-1 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of end-stage hallux rigidus.

1 Lau JT, Daniels TR. Outcomes following cheilectomy and interpositional arthroplasty in hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:462-470.

2 Gould N, Schneider W, Ashikaga T. Epidemiological survey of foot problems in the continental United States: 1978-1979. Foot Ankle Int. 1980;1:8-10.

3 Coughlin MJ, Shurnas PS. Hallux Rigidus: Demographics, etiology, and radiographic assessment. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:731-743.

4 Hattrup SJ, Johnson KA. Subjective results of hallux rigidus following treatment with cheilectomy. Clin Orthop Related Res. 1988;226:182-191.

5 Mann RA, Clanton TO. Hallux rigidus: Treatment by cheilectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:400-406.

6 Feltham GT, Hanks SE, Marcus RE. Age-based outcomes of cheilectomy for the treatment of hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:192-197.

7 Coughlin MJ, Shurnas PS. Hallux rigidus. Grading and long-term results of operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2072-2088.

8 Easley ME, Davis WH, Anderson RB. Intermediate to long-term follow-up of medial-approach dorsal cheilectomy for hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:147-152.

9 Henry AP, Waugh W, Wood H. The use of footprints in assessing the results of operations for hallux valgus: A comparison of Keller’s operation and arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57:478-481.

10 Love TR, Whynot AS, Farine I, Lavoie M, Hunt L, Gross A. Keller arthroplasty: A prospective review. Foot Ankle. 1987;8:46-54.

11 Keiserman LS, Sammarco VJ, Sammarco GJ. Surgical treatment of hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Clin N Am. 2005;10:75-96.

12 Hamilton W, O’Malley MJ, Thompson FM, Kovatis PE. Capsular interpositional arthroplasty for severe hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:68-70.

13 Kennedy JG, Chow FY, Dines J, Gardner M, Bohne WH. Outcomes after interposition arthroplasty for treatment of hallux rigidus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;445:210-215.

14 Barca F. Tendon arthroplasty of the first metatarsophalangeal joint in hallux rigidus: Preliminary communication. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:222-228.

15 Coughlin MJ, Shurnas PS. Soft-tissue arthroplasty for hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:661-672.

16 Brage ME, Ball ST. Surgical options for salvage of end-stage hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Clin N Am. 2002;7:49-73.

17 Curtis MJ, Myerson M, Jinnah RH, Cox QG, Alexander I. Arthrodesis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint: A biomechanical study of internal fixation techniques. Foot Ankle. 1993;14:395-399.

18 Politi J, John H, Njus G, Bennett GL, Kay DB. First metatarsal-phalangeal joint arthrodesis: A biomechanical assessment of stability. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:332-337.

19 Goucher NR, Coughlin MJ. Hallux metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis using dome-shaped reamers and dorsal plate fixation: A prospective study. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:869-876.

20 Flavin R, Stephens MM. Arthrodesis of the first metatarsophalangeal joint using a dorsal titanium contoured plate. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:783-787.

21 Cracchiolo A3rd, Weltmer JBJr, Lian G, Dalseth T, Dorey F. Arthroplasty of the first metatarsophalangeal joint with a double-stem silicone implant. Results in patients who have degenerative joint disease, failure of previous operations, or rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:552-563.

22 Swanson AB, de Groot SG. Use of grommets for flexible hinge implant arthroplasty of the great toe. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;340:87-94.

23 Sebold EJ, Cracchiolo A3rd. Use of titanium grommets in silicone implant arthroplasty of the hallux metatarsophalangeal joint. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:145-151.

24 Esway J, Conti SF. Joint replacement in the hallux metatarsophalangeal joint. Foot Ankle Clin N Am. 2005;10:97-115.

25 Pulavarti RS, McVie JL, Tulloch CJ. First metatarsophalangeal joint replacement using the Bio-Action great toe implant: Intermediate results. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:1033-1037.

26 Fuhrmann RA, Wagner A, Anders JO. First metatarsophalangeal joint replacement: The method of choice for end-stage hallux rigidus? Foot Ankle Clin N Am. 2003;8:711-721.

27 Townley CO, Taranow WS. A metallic hemiarthroplasty resurfacing prosthesis for the hallux metatarsophalangeal joint. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:575-580.

28 Taranow WS, Moutsatson MJ, Cooper JM. Contemporary approaches to Stage II and III hallux rigidus: The role of metallic hemiarthroplasty of the proximal phalanx. Foot Ankle Clin N Am. 2005;10:713-728.

29 Konkel KF, Menger AG. Mid-term results of titanium hemi-great toe implants. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:922-929.

30 O’Doherty DP, Lowrie IG, Magnussen PA, Gregg PJ. The management of the painful first metatarsophalangeal joint in the older patient. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72-B:839-842.

31 Gibson A, Thomson CE. Arthrodesis or total replacement arthroplasty for hallux rigidus. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:680-690.

32 Raikin SM, Ahmad J, Pour AE, Abidi N. Comparison of arthrodesis and metallic hemiarthroplasty of the hallux metatarsophalangeal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1979-1985.