Chapter 70 What Is the Best Treatment for End-Stage Ankle Arthritis?

Hip and knee arthroplasties are two of the most successful operations in the past century. For management of end-stage ankle arthritis, however, arthrodesis continues to be the mainstay of an orthopedic practice. This is in part due to the early catastrophic failures of the “first-generation” ankle arthroplasties and the high patient satisfaction after an ankle arthrodesis. Despite the initial failures of ankle arthroplasties, several individuals remained committed to the possibilities of replacing the ankle joint, and their persistence has resulted in the introduction of “second- and third-generation” ankle implants.1,2 Preliminary clinical results are promising, again giving rise to total ankle arthroplasty as an option for managing end-stage arthritis. These developments have prompted the current debate at many national and international meetings regarding the role of ankle arthroplasty in the management of end-stage ankle arthritis. This chapter briefly reviews the evidence that exists in the literature for all treatment options available for the operative management of end-stage ankle arthritis; however, the primary focus is to assess the level of evidence regarding ankle fusion versus arthroplasty and to provide the reader with treatment guidelines for their patients.

ANKLE ARTHRODESIS

Ankle arthrodesis for end-stage arthritis was first described by Albert in 1879,3 and for almost 100 years, this was the only option offered to patients with severe ankle pathology. Little information has been published on the topic. Since the 1960s, numerous studies have looked at various aspects of ankle arthrodesis: techniques of fusion, fusion rates, open versus arthroscopic fusion, position of fusion, patient satisfaction, functional outcomes, gait analysis, long-term results with focus on the health of the ipsilateral hindfoot joints, and more recently, comparison with normal control populations. These studies are largely based on Level III and IV evidence.

With regard to technique of arthrodesis, the classic Level IV retrospective study authored by J. Charnley4 and published in 1951 was the first to demonstrate that compression across a fusion site optimizes bone healing. Charnley4 describe compression with external fixation, and this technique was used for more than two decades. During the late 1970s and 1980s, the use of internal fixation increased in frequency. In 1991, Moeckel and colleagues,5 in a Level III study, compared external fixation with internal fixation and demonstrated an increased incidence of nonunion, delayed union, and infection in the external fixation group. More recently, circular external fixators with fine wires under tension are being used with increased frequency. The proponents of this technique suggest that the advantages are earlier weight bearing, ability to correct deformities during the postoperative follow-up phase, respect for soft tissues, more stable fixation, and fewer problems with prominent internal fixation.6,7 Opponents argue that the procedure is more complex, more expensive, and more labor intensive, with increased complications such as pin-tract infections. To date, no comparative or cost analysis studies have been published. Level III studies have suggested that external fixation is advantageous in the presence of infection, bone loss, talar avascular necrosis, or severe deformity6–8; however, no comparative studies have been performed.

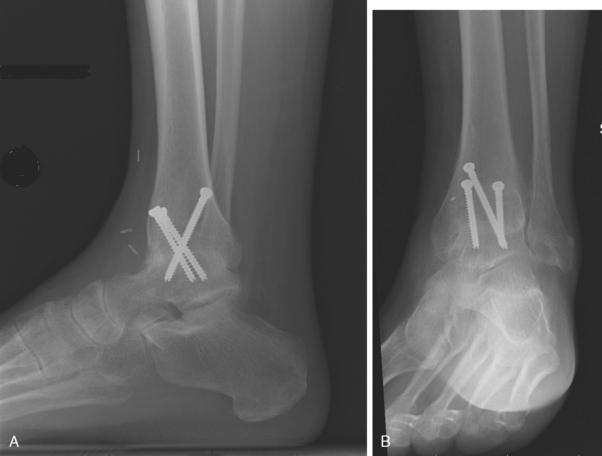

Studies comparing screw versus plate fixation have found an improved rate of union with screws.9–14 Screw fixation can be obtained with less soft-tissue stripping. This, combined with better compression at the fusion site, may account for the difference. Holt and coauthors10 describe a technique using three screws for fixation whereas preserving the medial and lateral malleoli. A fibular osteotomy is performed and, after denuding the cartilage, it is secured to the tibia and talus with compression screws. A second screw is placed from the medial malleolus into the talus, and then a third screw, the so-called home-run screw, is inserted from the posterior malleolus into the neck of the talus. This screw is of primary importance because it stabilizes plantarflexion and dorsiflexion forces (Fig. 70-1). Laboratory studies have shown that two crossed screws create a more rigid construct than two parallel screws.15 Cadaveric studies have shown that the use of three screws has the advantage of increased compression and better resistance to torque.16 These variations aside,9–11,13,14,16 most surgeons would agree that a minimum of two screws is necessary for adequate stability. Stability can be improved further by adding a fibular strut graft17; the use of a T-plate has been shown on cadavers to provide the stiffest construct when compared with other types of fixation, but it requires more soft-tissue dissection.18,19

Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis was introduced in 1983 by Schneider and popularized by others.20,21 Since then, numerous articles have been published with the primary focus on surgical technique, time to fusion, duration of admission to hospital, and fusion rates.20–34 Proponents of arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis advocate shorter operating room time, equivalent fusion rates to open methods, shorter hospital stay, and decreased wound healing problems. Again, these observations are based on Level III and IV evidence. Only two comparative studies,22,34 both of which are retrospective (Level III), offer only marginal support for the aforementioned advantages of arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. All agree that the procedure requires familiarity with arthroscopic skills for small joints and is indicated only in patients with minimal deformity at the ankle joint level.

Optimal position of ankle fusion has been studied closely in several Level III retrospective comparative clinical series.35–38 These studies have demonstrated that patients fused in greater than 10 degrees of equinus have a vaulting gait, increased knee extension and recurvatum, laxity of the medial collateral ligament of the knee, and slower walking speeds. These abnormalities were not observed in patients whose ankles were fused in a neutral position.36–38 It was also observed that when the hindfoot was in varus, patients reported increased pain and callus formation along the lateral border of the foot.36 Current recommendations are to position the hindfoot in neutral dorsiflexion, slight valgus, external rotation equal to the opposite side, and position the talus directly under or slightly posterior to the midline of the tibia.

Overall patient satisfaction after ankle arthrodesis was good. A number of articles published between 1960 and 2006 demonstrated a high satisfaction rate, good relief of pain, and improved function. Most of these articles were retrospective case series studies with no control group. One Level III intermediate follow-up study compared outcomes of ankle arthrodesis with a normal control population, and it demonstrated that there were substantial differences between the two groups with regard to physical function and pain39; however, many of the patients treated with arthrodesis remained satisfied with their results.

Several Level III long-term studies demonstrated a high incidence of ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis after ankle arthrodesis, particularly of the subtalar joint (Fig. 70-2).35,40–45 Two articles with more than a 20-year follow-up period demonstrated that more than 60% of the patients continue to be satisfied with their results despite the high prevalence of ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis.40,46 Only two studies have assessed the preoperative radiographs to determine the presence of preexisting ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis.46,47 Sheridan and coworkers46 demonstrated the presence of preexisting subtalar arthritis in 77.5% of patients with end-stage ankle arthritis and suggested that ankle arthrodesis does not necessarily lead to progressive ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis because it is often present before surgery. Daniels and researchers47 identified progression of subtalar arthritis in 4 of 26 (15%) patients in an intermediate follow-up study and progression of calcaneocuboid arthritis from stage 2 to 5 in one patient. Trauma has been identified as the most common causative factor of ankle arthritis.48 What is not known is whether the preexisting ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis is the result of the stiffness of the arthritic ankle or is caused by the original trauma, or a combination of both. Regardless of the causative factor, it can be concluded that long-term patients with ankle arthritis or ankle arthrodesis, or both, have a high incidence of ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis with the subtalar joint most commonly affected. Level III evidence exists that the presence of ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis does compromise the functional outcome of the patient after ankle arthrodesis.45,49 None of the long-term studies demonstrated an increased incidence of knee or metatarsophalangeal arthritis on either the ipsilateral or contralateral extremities.40,46

Articles that have assessed the effects of an ankle arthrodesis on gait have indicated that the abnormal kinetics and kinematics are most evident through the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot, with lesser effects on the knee, hip, and pelvis.35–38,47,50,51 All the studies cited earlier are retrospective reviews and considered Level III evidence. Although some variability exists in the results of gait analysis, patients with hindfoot fusions generally have the following gait characteristics: shortened stride length, decreased cadence, slower walking speeds, earlier heel raise during stance phase, increased anterior tilt of the tibia during midstance, increased forefoot plantar pressures with the forefoot ground reactive forces (GRF) shifted posterior during terminal stance, increased hip flexion, earlier knee extension during stance, diminished hindfoot motion, and increased midfoot motion. Studies that have assessed the effects of footwear on gait have indicated that the gait pattern further normalizes with footwear, particularly if there is a slight elevation in the heel and a forefoot rocker36–38; however, what continues to persist are early heel rise, posterior shift of the GRFs, and early extension of the knee.50 Beyaert and colleagues50 have suggested that the early heel rise and increased anterior tibial tilt during midstance increases the shear forces to the midtarsal joints and is a possible reason for the increased incidence of ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis after ankle arthrodesis. Weiss and coworkers,52 in a prospective, Level II, comparative study, assessed the effects of ankle/hindfoot arthrodesis on the function of the knee and hip. This study was not isolated to arthrodesis of the ankle alone, but it is the only prospective gait study that focused on the kinetic and kinematic outcomes of the ipsilateral hip and knee joints. It demonstrated that the overlying leg joints experience an improvement in joint motion, muscle-generated joint moments, and work during walking after arthrodesis.

ANKLE ARTHROPLASTY

As is evident from the previous discussion, ankle arthrodesis is considered by many experts to provide a good functional outcome for their patients. However, the long-term consequences of ankle fusion consist of subtalar arthritis, which produces poor functional outcomes because of the stiff and painful subtalar joint complex. A pantalar fusion to address painful hindfoot arthritis below an ankle fusion produces significant functional limitations.54,55

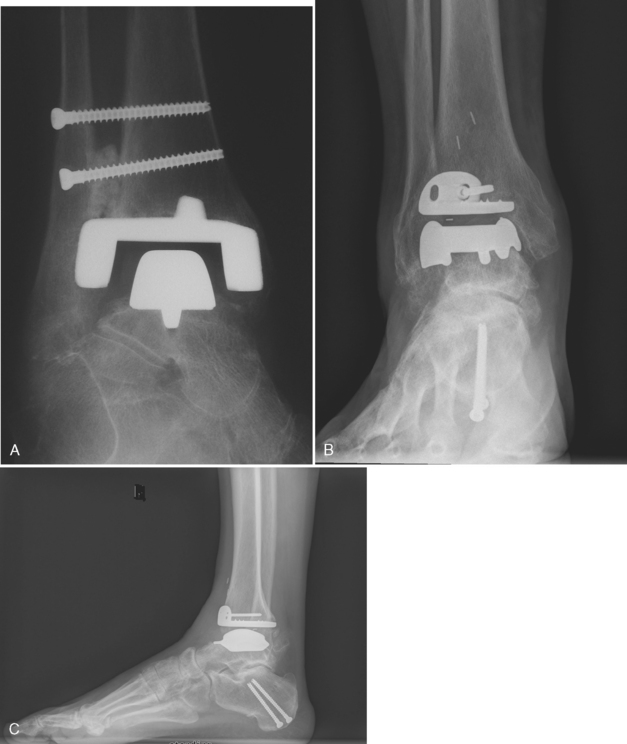

It is beyond the scope of this article to assess in detail the types of ankle implants utilized today. In brief, there are fixed bearing (two-component) and mobile bearing (three-component) designs. The two-component designs have the polyethylene that locks into the tibial component, whereas three-component designs have a polyethylene that articulates with the tibial and talar component allowing for motion at both surfaces (Fig. 70-3).

There has been a gradual trend toward a three-component, mobile-bearing implant that requires minimal bone resection.56–58 The disadvantages of the two-component design are that more bone resection is required and there is less room for error in positioning of the components.59,60 However, no studies have compared the outcomes of three-component and two-component designs.

Current clinical outcome studies of the newer ankle arthroplasties have determined the following: patients have a substantial relief of pain, improvement in their function and gait, and the implant 5- to 10-year survival rates are acceptable but not equivalent to knee or hip arthroplasty.1,2,56,61–84 The most current and comprehensive review is a Level III meta-analysis of 10 total ankle arthroplasty articles published between 1998 and 2005 that meet a strict inclusion criteria.85 The 5- and 10-year implant survival rates after total ankle arthroplasty were 78% (95% confidence interval, 69.0–87.6%) and 77% (95% confidence interval, 63.3–90.8%), respectively.

To date, all of the ankle arthroplasty articles assess the short- and mid-term results. The longest follow up is on the two-component Agility design by Knecht and colleagues75 with an average follow-up period of 9 years. Long-term follow-up of the first-generation total ankle arthroplasties showed extremely poor results and prompted a period when ankle joint arthroplasties were rarely performed.86–92 It is not known yet whether a similar fate awaits the second- and third-generation ankle joint arthroplasties.

Several Level IV retrospective articles have been published on the feasibility of salvaging a failed total ankle arthroplasty with arthrodesis,93–96 all of which have demonstrated an increased complication rate such as nonunion and infection with a prolonged recovery. This further emphasizes the cautious approach that should be taken when considering a young patient for ankle arthroplasty.

If ankle arthroplasty is to truly offer the patient an advantage over an ankle arthrodesis, it would have to allow for enough motion to normalize gait. Several studies have assessed the gait of patients who have undergone total ankle arthroplasty with the more recent two- and three-component designs.64,67, 83, 97 Two of these studies provide Level II evidence83,97 and two provide Level III evidence64,67 that gait after this surgery is improved and approaches more normal kinetic and kinematic parameters. There is improved dorsiflexion of the ankle during the stance phase, improved muscle function, and increased cadence and stride length. GRF at midstance are improved, but patients continue to demonstrate decreased vertical peak pressures during the terminal stance phase.67 The improved dorsiflexion during the stance phase may help decrease the abnormal shear forces to the subtalar joint complex, thereby decreasing the incidence of progressive ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis. A Level III meta-analysis by Soohoo and coworkers98 assessed reoperation rates after ankle arthrodesis versus arthroplasty and demonstrated a decreased incidence of patients requiring subtalar fusion after ankle arthroplasty.

It is important to note that none of the gait parameters was completely normalized, and comparative studies to ankle arthrodesis do not exist. Valderrabano and researchers’83 Level II study assessing muscle function and rehabilitation before and after ankle arthroplasty determined that total ankle arthroplasty improved muscle function (torque, electromyographic intensity). However, after 1 year, patients did not reach the level of the contralateral healthy leg and the electromyographic frequency remained unchanged.

Fresh Ankle Osteochondral Allografts

The outcomes of fresh ankle osteochondral allografts for end-stage ankle arthritis have been reported in a retrospective Level IV review by Brage and investigators,99,100 where 11 patients were managed for an average of 33 months, and a successful outcome was identified in 6 of the 11 patients. The author concludes that this procedure is indicated in young patients with end-stage ankle arthritis as an alternative to ankle joint arthroplasty. To date, this procedure is highly experimental and should be restricted to a tertiary care practice with a close and continuous follow-up.

Ankle Joint Distraction

Articular distraction of the ankle joint with an external fixation device101–106 has been advocated for patients with severe end-stage arthritis who are candidates for arthrodesis. The procedure involves application of a ringed external fixator to the distal tibial and foot after open or arthroscopic debridement. The joint is distracted a total of 5 mm, at 1-mm increments per day. Weight bearing is allowed, and hinges are applied to the fixator at 6 to 12 weeks to allow ankle flexion and extension. The fixator is removed at an average of 15 weeks after application. Marijnissen and coworkers105 report on 46 patients with an average follow-up of 2.8 ± 0.3 years: 13 patients withdrew from the study and underwent an arthrodesis. The remaining patients reported a significant reduction in pain (P < 0.0001), and improvement in function (P < 0.0001) and clinical condition (P < 0.0001). The ankle range of motion improved, but not significantly. Radiographically, the joint space increased by 17% at the 1-year and 27% at the 3-year follow-up examination (P < 0.05). The functional and clinical outcome scores were significantly better at the 3-year follow-up examination (P < 0.05), suggesting that the clinical picture improved with time. A more recent Level IV long-term retrospective clinical series of 25 patients with more than 7 years of follow-up determined a 73% success rate.106

Acevedo and Myerson107 report on a group of nine patients who underwent debridement and acute distraction (average, 5.8 mm; range, 4.5–8 mm). The fixator was removed at an average of 11 weeks. Only three patients reported functional improvement at the 1-year follow-up mark, and three underwent arthrodesis of the ankle at an average of 12 months after the distraction procedure. Although this treatment holds promise, data supporting a successful outcome are limited to Level III retrospective reviews published by a single group of physicians.

SUMMARY

After thorough review of the literature, the only expert advice we can offer is that the short-term outcomes of ankle fusion and arthroplasty are equivalent. Does the motion allowed for by an ankle arthroplasty offer sufficient benefits to the patient to make the risks for a difficult revision worthwhile? Does it decrease the incidence of symptomatic ipsilateral hindfoot arthritis? Does the improved gait over arthrodesis offer any long-term benefits to the patient? None of these questions can be answered by the current literature. Table 70-1 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of end-stage ankle arthritis.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Pyevich MT, Saltzman CL, Callaghan JJ, Alvine FG. Total ankle arthroplasty: A unique design. Two to twelve-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:1410-1420.

2 Kofoed H, Lundberg-Jensen A. Ankle arthroplasty in patients younger and older than 50 years: A prospective series with long-term follow-up. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:501-506.

3 Albert E. Zur resektion des kniegelenkes. Wien Med Press. 1879;20:705-708.

4 Charnley J. Compression arthrodesis of the ankle and shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg. 1951;33-B:180-191.

5 Moeckel B, Patterson BM, Inglis AE, Sculco TP. Ankle arthrodesis. A comparison of internal and external fixation. Clin Orthop. 1991;268:78-83.

6 Eylon S, Porat S, Bor N, Leibner ED. Outcome of Ilizarov ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;288:73-79.

7 Salem K, Kinzl L, Schmelz A. Ankle arthrodesis using Ilizarov ring fixators: A review of 22 cases. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:764-770.

8 Eralp L, Kocaoglu M, Yusof NM, Bulbul M. Distal tibial reconstruction with use of a circular external fixator and an intramedullary nail. The combined technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2218-2224.

9 Chen Y-J, Huang TJ, Shih HN, Hsu KY, Hsu RW. Ankle arthrodesis with cross-screw fixation. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:473-478.

10 Holt E, Hansen ST, Mayo KA, Sangeorzan BJ. Ankle arthrodesis using internal screw fixation. Clin Orthop. 1991;268:56-64.

11 Mann RA, Rongstad KM. Arthrodesis of the ankle: A critical analysis. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:3-9.

12 Maurer R, Cimino WR, Cox CV, Satow GK. Transarticular cross-screw fixation: A technique of ankle arthrodesis. Clin Orthop. 1991;268:56-64.

13 Sward L, Hughes JS, Howell CJ, Colton CL. Posterior internal compression arthrodesis of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:752-756.

14 Morgan C, Henke JA, Bailey RW, Kaufer H. Long-term results of tibiotalar arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67-A:546-549.

15 Friedman RL, Glisson RR, Nunley JA2nd. A biomechanical comparative analysis of two techniques for tibiotalar arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:301-305.

16 Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Fitsialos D, Hedman TP. Arthrodesis of the ankle. A comparison of two versus three screw fixation in a crossed configuration. Clin Orthop.; 304; 1994; 195-199.

17 Thordarson DB, Markolf KL, Cracchiolo A3rd. Arthrodesis of the ankle with cancellous-bone screws and fibular strut graft. Biomechanical analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1359-1363.

18 Dohm MP, Benjamin JB, Harrison J, Szivek JA. A biomechanical evaluation of three forms of internal fixation used in ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:297-300.

19 Scranton PEJr, Fu FH, Brown TD. Ankle arthrodesis: A comparative clinical and biomechanical evaluation. Clin Orthop.; 151; 1980; 234-243.

20 Ferkel R, Hewitt M. Long-term results of arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:275-280.

21 Collman D, Kaas M, Schuberth J. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: Factors influencing union in 39 consecutive patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:1079-1085.

22 Myerson M, Quill G. Ankle arthrodesis. A comparison of an arthroscopic and an open method of treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 268; 1991; 84-95.

23 Corso S, Zimmer T. Technique and clinical evaluation of arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:585-590.

24 Gougoulias N, Agathangelidis F, Parsons S. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:695-706.

25 Glick JM, Morgan CD, Myerson MS, Sampson TG, Mann JA. Ankle arthrodesis using an arthroscopic method: Long-term follow-up of 34 cases. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:428-434.

26 Kats J, van Kampen A, de Waal-Malefijt M. Improvement in technique for arthroscopic ankle fusion: Results in 15 patients. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:46-49.

27 Dent C, Patil M, Fairclough J. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:830-832.

28 Rippstein P, Kumar B, Muller M. Ankle arthrodesis using the arthroscopic technique. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2005;17(4-5):442-456.

29 Turan I, Wredmark T, Fellander-Tsai L. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 320; 1995; 110-114.

30 Wasserman L, Saltzman C, Amendola A. Minimally invasive ankle reconstruction: Current scope and indications. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:247-253.

31 Winson I, Robinson D, Allen P. Arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:343-347.

32 Zvijac J, Lemak L, Schurhoff MR, Hechtman KS, Uribe JW. Analysis of arthroscopically assisted ankle arthrodesis. Arthroscopy. 2002;18:70-75.

33 Cameron S, Ullrich P. Arthroscopic arthrodesis of the ankle joint. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:21-26.

34 O’Brien TS, Hart TS, Shereff MJ, Stone J, Johnson J. Open versus arthroscopic ankle arthrodesis: A comparative study. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:368-374.

35 Mazur J, Schwartz E, Simon S. Ankle arthrodesis. Long-term follow-up with gait analysis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61:964-975.

36 Buck P, Morrey B, Chao E. The optimum position of arthrodesis of the ankle. A gait study of the knee and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1052-1062.

37 King HA, Watkins TBJr, Samuelson KM. Analysis of foot position in ankle arthrodesis and its influence on gait. Foot Ankle. 1980;1:44-49.

38 Hefti FL, Baumann JU, Morscher EW. Ankle joint fusion— determination of optimal position by gait analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1980;96:187-195.

39 Thomas R, Daniels T, Parker K. Gait analysis and functional outcomes following ankle arthrodesis for isolated ankle arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:526-535.

40 Coester L, Saltzman CL, Leupold J, Pontarelli W. Long-term results following ankle arthrodesis for post-traumatic arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:219-228.

41 Lynch A, Bourne R, Rorabeck C. The long-term results of ankle arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:113-116.

42 Morrey B, Wiedman G. Complications and long-term results of ankle arthrodesis following trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62-A(5):777-784.

43 Ahlberg A, Henricson A. Late results of ankle fusion. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52:103-105.

44 Boobbyer G. The long-term results of ankle arthrodesis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1981;52:107-110.

45 Fuchs S, Sandmann C, Skwara A, Chylarecki C. Quality of life 20 years after arthrodesis of the ankle. A study of adjacent joints. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:994-998.

46 Sheridan BD, Robinson DE, Hubble MJ, Winson IG. Ankle arthrodesis and its relationship to ipsilateral arthritis of the hind- and mid-foot. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:206-207.

47 Daniels TR, Thomas RH, Parker K: Gait Analysis and Functional Outcomes of Isolated Ankle Arthrodesis. Presented at International Federation of Foot and Ankle Societies Triennial Scientific Meeting. San Francisco, CA, 2002.

48 Saltzman CL, Salamon ML, Blanchard GM, Huff T, Hayes A, Buckwalter JA, Amendola A. Epidemiology of ankle arthritis: Report of a consecutive series of 639 patients from a tertiary orthopaedic center. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:44-46.

49 Buchner M, Sabo D. Ankle fusion attributable to posttraumatic arthrosis: A long-term followup of 48 patients. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;406:155-164.

50 Beyaert C, Sirveaux F, Paysant J, Molé D, André JM. The effect of tibio-talar arthrodesis on foot kinematics and ground reaction force progression during walking. Gait Posture. 2004;20:84-91.

51 Wu WL, Su FC, Cheng YM, Huang PJ, Chou YL, Chou CK. Gait analysis after ankle arthrodesis. Gait Posture. 2000;11:54-61.

52 Weiss R, Broström E, Stark A, Wick MC, Wretenberg P. Ankle/hindfoot arthrodesis in rheumatoid arthritis improves kinematics and kinetics of the knee and hip: A prospective gait analysis study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46:1024-1028.

54 Acosta R, Ushiba J, Cracchiolo A3rd. The results of a primary and staged pantalar arthrodesis and tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis in adult patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:182-194.

55 Papa J, Myerson M. Pantalar and tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis for post-traumatic osteoarthritis of the ankle and hindfoot. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74:1042-1049.

56 Alvine FG. Total ankle arthroplasty. Myerson MS, editor. Foot and Ankle Disorders.; Vol. 2; 2000; WB Saunders Company: Philadelphia; 1087.

57 Saltzman C, McIff TE, Buckwalter JA, Brown TD. Total ankle replacement revisited. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2000;30:56-67.

58 Thomas RH, Daniels TR. Ankle arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:923-936.

59 Saltzman C, Tochigi Y, Rudert MJ, McIff TE, Brown TD. The effect of agility ankle prosthesis misalignment on the peri-ankle ligaments. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;424:137-142.

60 Tochigi Y, Rudert MJ, Brown TD, McIff TE, Saltzman CL. The effect of accuracy of implantation on range of movement of the Scandinavian total ankle replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:736-740.

61 Bonnin M, Judet T, Colombier JA, Buscayret F, Graveleau N, Piriou P. Midterm results of the Salto Total Ankle Prosthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;424:6-18.

62 Buechel FF, Pappas MJ. Survivorship and clinical evaluation of cementless, meniscal-bearing total ankle replacements. Semin Arthroplasty. 1992;3:43-50.

63 Buechel FF, Pappas MJ, Iorio LJ. New Jersey low contact stress total ankle replacement: Biomechanical rationale and review of 23 cementless cases. Foot Ankle. 1988;8:279-290.

64 Conti S, Lalonde K, Martin R. Kinematic analysis of the agility total ankle during gait. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:980-984.

65 Conti SF: Gait before and after total ankle arthroplasty with a comparison to arthrodesis. Presented at International Federation of Foot and Ankle Societies Triennial Scientific Meeting. San Francisco, CA, IFFAS, 2002.

66 Doets H, Brand R, Nelissen R. Total ankle arthroplasty in inflammatory joint disease with use of two mobile-bearing designs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1272-1284.

67 Doets H, van Middelkoop M, Houdijk H, Nelissen RG, Veeger HE. Gait analysis after successful mobile bearing total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:313-322.

68 Haskell A, Mann R. Ankle arthroplasty with preoperative coronal plane deformity: Short-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;424:98-103.

69 Hintermann B, Valderrabano V. Total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8:375-405.

70 Hintermann B, Valderrabano V, Dereymaeker G, Dick W. The HINTEGRA ankle: Rationale and short-term results of 122 consecutive ankles. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 424; 2004; 57-68.

71 Hintermann B, Valderrabano V, Knupp M, Horisberger M. The HINTEGRA ankle: short- and mid-term results. Orthopade. 2006;35:533-545.

72 Hurowitz E, Gould JS, Fleisig GS, Fowler R. Outcome analysis of agility total ankle replacement with prior adjunctive procedures: Two to six year followup. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:308-312.

73 Jensen NC, Kroner K. Total ankle joint replacement: A clinical follow up. Orthopedics. 1992;15:236-239.

74 Kirkup J. Richard Smith ankle arthroplasty. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:301-304.

75 Knecht SI, Estin M, Callaghan JJ, Zimmerman MB, Alliman KJ, et al. The agility total ankle arthroplasty. Seven to sixteen-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1161-1171.

76 Kofoed H. Ankle arthroplasty: Indications, alignment, stability and gain in mobility. In: Kofoed H, editor. Current Status of Ankle Arthroplasty. Heidelberg: Springer; 1998:20.

77 Kofoed H, Sorensen TS. Ankle arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis: Prospective long-term study of cemented replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:328-332.

78 Kopp F, Patel MM, Deland JT, O’Malley MJ. Total ankle arthroplasty with the Agility prosthesis: Clinical and radiographic evaluation. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:97-103.

79 San Giovanni T, Keblish DJ, Thomas WH, Wilson MG. Eight-year results of a minimally constrained total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:418-426.

80 Su EP, Kahn B, Figgie MP. Total ankle replacement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 424; 2004; 32-38.

81 Takakura Y, Tanaka Y, Kumai T, Sugimoto K, Ohgushi H. Ankle arthroplasty using three generations of metal and ceramic prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 424; 2004; 130-136.

82 Tanaka Y, Takakura Y. The TNK ankle: Short- and mid-term results. Orthopade. 2006;35:546-551.

83 Valderrabano V, Nigg BM, von Tscharner V, Frank CB, Hintermann B. Total ankle replacement in ankle osteoarthritis: An analysis of muscle rehabilitation. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:281-291.

84 Wood PL, Deakin S. Total ankle replacement. The results in 200 ankles. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:334-341.

85 Haddad S, Coetzee JC, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Nalysnyk L. Intermediate and long-term outcomes of total ankle arthroplasty and ankle arthrodesis. A systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1899-1905.

86 Bolton-Maggs BG, Sudlow RA, Freeman MA. Total ankle arthroplasty. A long-term review of the London Hospital experience. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:785-790.

87 Kitaoka HB, Patzer GL, Ilstrup DM, Wallrichs SL. Survivorship analysis of the Mayo total ankle arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76:974-979.

88 McGuire MR, Kyle RF, Gustilo RB, Premer RF. Comparative analysis of ankle arthroplasty versus ankle arthrodesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 226; 1988; 174-181.

89 Newton SE3rd. Total ankle arthroplasty. Clinical study of fifty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:104-111.

90 Stauffer RN. Salvage of painful total ankle arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 170; 1982; 184-188.

91 Stauffer RN, Segal NM. Total ankle arthroplasty: Four years’ experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 160; 1981; 217-221.

92 Wynn AH, Wilde AH. Long-term follow-up of the Conaxial (Beck-Steffee) total ankle arthroplasty. Foot Ankle. 1992;13:303-306.

93 Groth HE, Fitch HF. Salvage procedures for complications of total ankle arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 224; 1987; 244-250.

94 Hopgood P, Kumar R, Wood P. Ankle arthrodesis for failed total ankle replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1032-1038.

95 Kitaoka HB, Romness DW. Arthrodesis for failed ankle arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1992;7:277-284.

96 Kotnis R, Pasapula C, Anwar F, Cooke PH, Sharp RJ. The management of failed ankle replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1039-1047.

97 Dyrby C, Chou LB, Andriacchi TP, Mann RA. Functional evaluation of the scandinavian total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:377-381.

98 Soohoo N, Zingmond D, Ko C. Comparison of reoperation rates following ankle arthrodesis and total ankle arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2143-2149.

99 Kim C, Jamali A, Tontz WJr, Convery FR, Brage ME, Bugbee W. Treatment of post-traumatic ankle arthrosis with bipolar tibiotalar osteochondral shell allografts. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:1091-1102.

100 Meehan R, McFarlin S, Bugbee W, Brage M. Fresh ankle osteochondral allograft transplantation for tibiotalar joint arthritis. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:793-802.

101 Van Valburg AA, van Roermund PM, Marijnissen AC, van Melkebeek J, Lammens J, et al. Joint distraction in treatment of osteoarthritis: A two-year follow-up of the ankle. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1999;7:474-479.

102 van Valburg AA, van Roermund PM, Marijnissen AC, Wenting MJ, Verbout AJ, Lafeber FP, Bijlsma JW. Joint distraction in treatment of osteoarthritis (II): Effects on cartilage in a canine model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2000;8:1-8.

103 van Valburg AA, van Roermund PM, Lammens J, van Melkebeek J, Verbout AJ, et al. Can Ilizarov joint distraction delay the need for an arthrodesis of the ankle? A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:720-725.

104 van Roermund PM, Lafeber FP. Joint distraction as treatment for ankle osteoarthritis. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:249-254.

105 Marijnissen AC, van Roermund PM, van Melkebeek J, Schenk W, Verbout AJ, et al. Clinical benefit of joint distraction in the treatment of severe osteoarthritis of the ankle: Proof of concept in an open prospective study and in a randomized controlled study. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:2893-2902.

106 Ploegmakers J, van Roermund PM, van Melkebeek J, Lammens J, Bijlsma JW, et al. Prolonged clinical benefit from joint distraction in the treatment of ankle osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005;13:582-588.

107 Acevedo JI, Myerson M. Reconstructive alternatives for ankle arthritis. Foot Ankle Clin. 1999;4:409-430.