Chapter 35 What Is the Best Treatment for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip?

The majority of high-quality research into developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) has focused on the neonatal period and early infancy. It was the introduction of hip ultrasound in the early 1980s that led to a paradigm shift in the diagnosis and management of DDH in this age group. Ultrasound allowed visualization of hip morphology in newborns and added further information to the physical examination of the hip. The main question posed by the introduction of ultrasound was whether better outcomes can be achieved by utilizing ultrasound as opposed to relying on clinical tests alone. Many questions followed: If ultrasound is utilized, at what age should it be done? Should all infants receive the test or only those with remarkable findings on physical examination? Which abnormal sonographic findings warrant immediate treatment, which warrant repeat scanning, and which hips can be discharged from any further follow-up?

Although hip ultrasound has the potential to contribute valuable information in hips with unclear findings on physical examination, its accuracy has never been well established from basic principles and remains unclear.1 As a result, not only physical examination but also ultrasound testing leaves much room for debate and uncertainty in the diagnosis and management of DDH.2,3

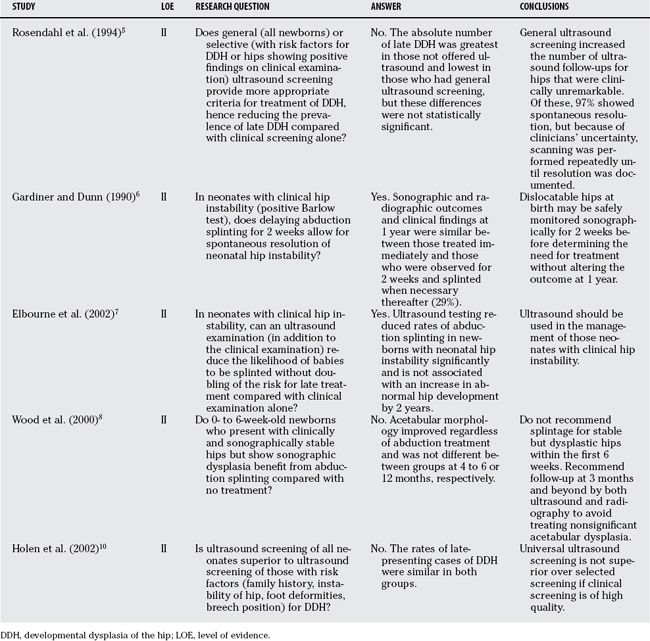

Uncertainty exists as to which forms of neonatal DDH warrant treatment and which will improve spontaneously; how long can we wait for a hip to improve on its own, and when is it justified to initiate costly treatment that includes serious risks, as well as burden to affected families. Randomized, controlled trials have been performed to answer some of these questions (Table 35-1). They were mainly driven by a desire to determine whether ultrasound can improve health outcomes in neonates with DDH. This chapter focuses on those areas of DDH studied by randomized, controlled trials.

TABLE 35-1 Research Questions of Randomized Clinical Trials on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in the Neonate

DIAGNOSIS

The neonate with DDH may reveal remarkable findings on clinical examination. Although the majority of the hips with a positive Barlow or Ortolani test reveal some form of DDH (high sensitivity), these tests are not positive in all patients with DDH (imperfect specificity). Clearly, factors such as the age of the patient and the experience of the examiner influence test performance. Therefore, the accuracy of these tests cannot be quantified by one single number. Limited hip abduction is another potential but unreliable clinical sign for DDH. In a sample of Dutch infants aged 3 to 10 months, the finding of unilateral limitation of abduction had an overall sensitivity for the diagnosis of DDH of 69%, a specificity of 54%, a positive predictive value of 43%, and a negative predictive value of 78%; 46% of infants without DDH exhibited definite limited abduction.4

Abnormalities of the neonatal hip can be grouped into clinical abnormalities (instability of the hip, dislocatability of the hip, limited unilateral abduction of the hip) and by sonographic abnormalities (sonographic instability, reduced femoral head coverage, shallow acetabulum). No standardized diagnostic criteria have been established, however, with which these abnormalities can be distinguished from forms of DDH that will not resolve spontaneously.3

Because abnormalities of the hip present at birth are modulated by ongoing growth and because resolution of less severe abnormalities (Barlow-positive hips) was reported in up to 95% of patients,5,6 a relevant question is up to which age treatment can be delayed without altering outcomes.

NEONATAL HIP INSTABILITY

Gardiner and Dunn6 performed a randomized clinical trial to address this question.6 Abduction splinting was delayed until the age of 10 to 14 days, or commenced immediately in neonates (≤2 days old) with dislocatable hips (positive Barlow test). All infants in the “delay group” were monitored by means of ultrasound at the age of 2 weeks and were treated thereafter if hips had not improved. Treatment became necessary in 29% of all infants. The trial revealed similar outcomes for those who received immediate treatment at the age of 2 days or younger, and for those who received delayed treatment (if it was still indicated because the hip did not resolve spontaneously) at the age of 2 weeks.

Based on the findings of this trial,6 the U.K. Collaborative Hip Trial group7 wanted to establish whether it was safe not to splint hips that were clinically suspect but seemed normal on ultrasound surveillance. Their concern was that such a regimen might increase the numbers of children requiring late treatment for DDH. The primary outcome of the trial was radiographic hip appearance at the age of 2 years. Eligible were infants 0 to 6 weeks old who had been diagnosed with neonatal hip instability by a senior physician.

How can these results be compared with those of Gardiner and Dunn’s trial?6 Gardiner and Dunn studied babies with dislocatable hips on clinical examination (positive Barlow test) and randomized them into early treatment or ultrasound and observation for 2 weeks. Also, the U.K. Collaborative Hip Trial group7 included such patients—that is, infants who presented with the same remarkable findings on clinical examination warranting immediate treatment. If this particular stratum is considered for comparison, the relative risk (i.e., the risk of an outcome among patients receiving an intervention, in comparison with patients not receiving the intervention of interest) to receive any form of treatment during the trial period was 30% for the ultrasound group. That is, the rate of receiving any form of treatment in the ultrasound group was one third of that in the nonultrasound group. This effect was similar to Gardiner and Dunn’s trial.6

SONOGRAPHIC DYSPLASIA IN CLINICALLY STABLE HIPS

Wood and colleagues8 investigated whether sonographically shallow hips that were stable on clinical and ultrasound examination should be treated. Infants who had either remarkable hips on physical examination or who were considered at risk for DDH received ultrasound scanning at the age of 2 to 6 weeks. Approximately 13.6% were found to have stable (<2 mm displacement of the femoral head from the floor of the acetabulum) but sonographically dysplastic (<40% femoral head cover) hips. These infants were randomly allocated to either splinting or observation alone. All patients were managed 6 and 12 weeks later by ultrasound. Radiographic outcomes were determined at the age of 3 to 4 months, and in some at the age of 12 months. Neither sonographic nor radiographic outcome parameters were significantly different between groups. The sample size of this study was small with a statistical power of less than 80%.

Based on results of retrospective studies, Graf and coauthors9 believe that treatment of sonographic dysplastic hips (Graf types IIc and D) must be initiated within the first 4 to 6 weeks of life; however, results from prospective studies suggest that such hips do well without treatment as long as they are stable.5 Because the outcome of untreated Graf types IIc and D hips has never been established in well-designed comparative studies, the significance of such sonographic findings remains unclear, especially in the long term. Sonographic monitoring of such hips seems to be sensible.

SCREENING

Rosendahl and coworkers5 managed 11,925 Norwegian newborns who underwent physical examination within the first 2 days of life. Newborns were assigned to one of three groups by convenience: general ultrasound screening, selective ultrasound screening of newborns found to be at high risk for DDH, and no ultrasound screening (allocation to the no-screening group if the sonographer was absent). The high-risk group included infants with hip dislocation, dislocatable hip, breech position, or family history of DDH (first- or second-degree relatives). Serial clinical examinations were performed in the first 2 years of life, supplemented by ultrasound tests for those in the ultrasound groups. All high-risk infants were referred for radiographs of the hips at 4 to 5 months of age. Ultrasound screening was performed within the first 2 days of delivery; modified Graf criteria (including hip morphology and hip stability) were applied.

Ortolani- or Barlow-positive hips were treated immediately with abduction splints, as were hips that were dislocated on ultrasound (Graf type III). The primary outcome of the trial was DDH discovered after the first month of life. There were 24 such cases, and they were classified by means of radiography in dysplasia, subluxation, and dislocation. The median age of late-presenting cases was 4.5 months. The total number was almost similar in the nonultrasound (n = 10) and selective ultrasound groups (n = 9), but lower in the universal ultrasound group (n = 5). The rates of late dislocations or subluxation were 0.3, 0.7, and 1.3 per 1000 live births, respectively. These differences were not significant, however. Three infants (nonscreening and selective screening groups) required surgery for dislocated hips.

Although no late presentations of DDH were observed after universal ultrasound screening, statistically, there was no difference among the 3 screening regimens, and ultrasound, therefore, was not superior to physical examination by well-trained personnel. However, like others studies,6,8 the results of this study suggest that the need for clinical follow-up can be minimized by the reassuring findings of a normal ultrasound test.

Holen and researchers10 investigated whether universal ultrasound screening is superior to selective ultrasound screening. After a physical examination by an experienced single pediatrician, a newborn’s risk factors for DDH were established. These included any form of instability of the hip (positive or uncertain Barlow test), positive family history, breech position, and foot deformities. Infants were randomized into 2 groups. One group received both physical and ultrasound examinations. Infants in the second group received ultrasound only if they had a risk factor. DDH detected after the first month of life was the primary outcome, and it was measured by sonographic and radiographic criteria, respectively. In the universal ultrasound group, 1 case (0.13/1000 live births) was found, and 5 were found in the selected ultrasound group (0.65/1000 live births). The relative risk for late detected DDH in the universal screening group was 0.21 (95% confidence interval, 0.03–1.45). This study clearly showed that universal ultrasound screening is not superior over selected screening if clinical screening is of high quality.

The authors raised the question whether ultrasound could have the potential to eradicate late-presenting cases of DDH because there was only 1 such case in their universal ultrasound screening group. Universal ultrasound screening was established in 1996 in Germany, and all newborns have been screened by means of ultrasound before the sixth week of life. Despite a population screening rate of more than 95%, 13% of infants required an operative procedure later on to treat DDH. Of interest, 13% of these hips were judged to be normal on ultrasound screening.11 These findings show that ultrasound screening may have the potential to reduce the number of late-presenting cases of DDH or the need for surgical treatment but will not eliminate them.

EXISTING GUIDELINES

The American Academy of Pediatrics12 recommend, based on a model-driven approach with a comprehensive synthesis of the evidence base, clinical screening for DDH by a trained health professional for all newborns. Ultrasound is not recommended except for girls born in the breech position. These infants should undergo either hip ultrasound at the age of 6 weeks or radiographs at 4 months because of the significantly high risk for DDH (absolute risk, 70–120/1000). Hips remarkable in the postnatal examination can be watched for 2 weeks or should be referred to an orthopedic specialist, but no abduction splinting is recommended at that stage.

The U.S. Preventative Services Task Force13 recommends against routine screening for DDH. The task force argues that the natural history of DDH is poorly defined, and there is lack of evidence that screening would improve health outcomes, although there is evidence that interventions have the potential to cause harm such as avascular necrosis of the hip.

The Canadian Task Force for Preventative Health Care14 recommend serial physical examination by a trained clinician in the periodic health examinations. Also, this guideline does not recommend ultrasound as a screening tool, not even in infants at high risk such as girls born in the breech position. The author argues that selective screening is ineffective in reducing the operating rates because most newborns have no risk factors.

The U.K. National Screening Committee recommends ultrasound to be used in the management of infants with clinical hip instability.15 Population screening programmes using ultrasound in all newborns have been implemented in some Mid-European countries where ultrasound is performed within the first 6 weeks of life.

Good evidence exists for the management of the dislocatable hip of the neonate. Treatment of such hips can be safely delayed until the age of 2 to 3 weeks without altering the final outcome. In fact, a large proportion of such hips will stabilize spontaneously within this period. Based on current evidence, treatment should be initiated if the hip is not improving beyond the age of 2 weeks.

Sufficient evidence does not exist to support general ultrasound screening. Two trials demonstrated that general ultrasound is not superior to selective ultrasound. If the physical examination is performed by well-trained and experienced personnel, ultrasound should be utilized for hips that show unclear findings on clinical examination because it will reduce the number of splinting. Girls born in the breech position have a significantly greater absolute risk (up to 12 times greater) for severe forms of DDH. Ultrasound screening of this subgroup within the first 6 weeks seems plausible. Table 35-2 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of DDH.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

1 Roposch A, Moreau NM, Uleryk E, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip: Quality of reporting of diagnostic accuracy for US. Radiology. 2006;241:854.

2 Woolacott NF, Puhan MA, Steurer J, et al. Ultrasonography in screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns: Systematic review. BMJ. 2005;330:1413.

3 Roposch A, Wright JG. Increased diagnostic information and understanding disease: Uncertainty in the diagnosis of developmental hip dysplasia. Radiology. 2007;242:355.

4 Castelein RM, Korte J. Limited hip abduction in the infant. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:668.

5 Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in the neonate: The effect on treatment rate and prevalence of late cases. Pediatrics. 1994;94:47.

6 Gardiner HM, Dunn PM. Controlled trial of immediate splinting versus ultrasonographic surveillance in congenitally dislocatable hips. Lancet. 1990;336:1553.

7 Elbourne D, Dezateux C, Arthur R, et al. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis and management of developmental hip dysplasia (UK Hip Trial): Clinical and economic results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:2009.

8 Wood MK, Conboy V, Benson MK. Does early treatment by abduction splintage improve the development of dysplastic but stable neonatal hips? J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:302.

9 Graf R. Ultrasound measurements of the newborn hip—comparison of two methods in 657 newborns. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:550.

10 Holen KJ, Tegnander A, Bredland T, et al. Universal or selective screening of the neonatal hip using ultrasound? A prospective, randomised trial of 15,529 newborn infants. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:886.

11 von Kries R, Ihme N, Oberle D, et al. Effect of ultrasound screening on the rate of first operative procedures for developmental hip dysplasia in Germany. Lancet. 2003;362:1883.

12 Lehmann HP, Hinton R, Morello P, et al. Developmental dysplasia of the hip practice guideline: Technical report. Committee on Quality Improvement, and Subcommittee on Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E57.

13 Screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip: Recommendation statement. US Preventative Services Task Force. Paediatrics. 2006;117:898.

14 Patel H. Preventive health care, 2001 update: Screening and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. CMAJ. 2001;164:1669.

15 Elliman DA, Dezateux C, Bedford HE. Newborn and childhood screening programmes: Criteria, evidence, and current policy. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:6.