Chapter 31 What Is the Best Treatment for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Skeletally Immature Individuals?

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury in a growing child is being diagnosed with some degree of frequency, probably because of increased skill in diagnostic ability including specialized imaging studies such as magnetic resonance imaging.1–7 The true incidence of ACL injury in the skeletally immature athlete is unknown. In a series of 1000 consecutive ACL injuries treated at the Cleveland Clinic, 5 patients were younger than 12 years.8

From insurance claim data in the United States for youth soccer leagues, the overall incidence rate is about 0.01% with 550 claims for ACL injury out of 6 million children and youths who were insured during the time period.9 Girls have been noted to be 2 to 9 times more likely to sustain this injury than boys.10

NATURAL HISTORY OF ANTERIOR CRUCIATE LIGAMENT INJURY IN CHILDREN

In adults, chronic ACL insufficiency leads to intra-articular damage. Meniscal tears and chondral damage occur in individuals who continue to participate in sports and recreational activities without the benefit of a stable knee.11–13 What is the evidence? A number of Level II and III studies confirm the same dismal prognosis in children with open physes; namely, if the ACL is left untreated, the patient has a markedly increased risk for development of meniscal tears and chondral damage leading to eventual osteoarthritis.4,5,14–18

Level III studies by Graf and colleagues,4 McCarroll and coworkers,5 and Angel and Hall1 all report on the high incidence of meniscal tears and the inability to resume preinjury activity levels. Level II studies by Aichroth and investigators,14 Pressman and researchers,18 and Kannus and Jarvinen19 have confirmed the results of these earlier studies.

MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Since the early 1990s, the orthopedic literature has discussed in depth the possibility of an ACL disruption in the growing child. Before these detailed descriptions, it was generally believed that children did not tear the ACL with the exception of the pediatric equivalent, namely, the tibial eminence fracture.20–23 With that background, it is important for the physician to have a high index of suspicion in a child presenting with a presumed hemarthrosis (swollen knee) after a knee injury.

In a number of series of knee injuries in the pediatric population, the incidence rate of ACL disruption has been reported to be as low as 10% and as high as 65% in series with the number of patients ranging from 35 to 138 patients.24–28

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

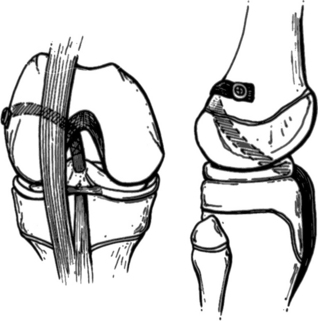

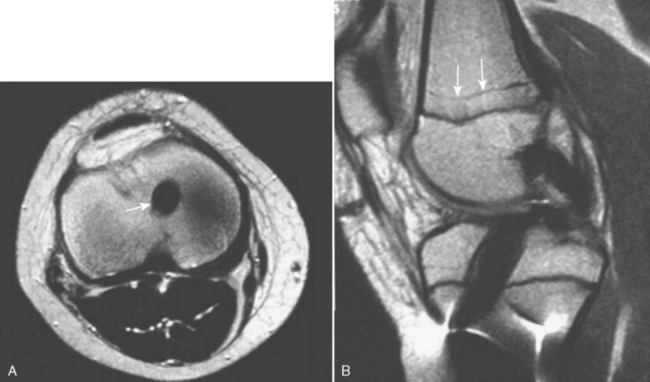

The decision to order magnetic resonance imaging still remains somewhat controversial. However, in 2007, it is recommended for patients with suspected ACL tears to be evaluated for meniscal tear and osteochondral lesions (such as a fracture or a “bone bruise”) (Fig. 31-1) (Level of Evidence V).

TREATMENT

Special Considerations in the Growing Child

Children with open growth plates may present challenges to the treating orthopedic surgeon familiar with reconstruction techniques used in adults. Most ACL reconstructions in adults use autograft tendon (hamstring or patellar tendon) to replace the torn ACL. The surgical technique involves a central drill hole in the proximal tibia and another in the distal femur to place the tendon graft to closely resemble the anatomic location of the normal ACL. Utilizing this surgical technique in a growing child may result in a growth arrest or altered growth in either the proximal tibia or the distal femur. Growth disturbances using conventional surgical techniques have been reported in both animal models29–31 and clinical series of reconstructions in pediatric patients.32–34

Is There a Place for Nonoperative Treatment?

A number of commercially available knee orthoses are available that theoretically prevent the knee instability seen in patients with chronic ACL insufficiency. Unfortunately, no evidence has been presented to show they prevent the dreaded consequences of further meniscal damage and chondral change despite the claims of rendering the knee more stable16–18 (Level of Evidence IV). Also, few growing children are willing to alter their active lifestyle and give up change-of-direction sports.

Operative Treatment

These surgical methods can be divided into the following categories:

Extra-articular Surgical Reconstruction.

Extra-articular surgical reconstruction was popular in adults in the 1970s. Unfortunately, the location of the graft in a nonanatomic location was unsuccessful in controlling anterior translation of the tibia on the femur. Nevertheless, these extra-articular reconstructions have been proposed as a “temporizing” procedure in the skeletally immature patient2,4, 5 (Level of Evidence IV). No evidence suggests that they will act any more efficiently than reported previously.

Physis-Sparing Reconstructions.

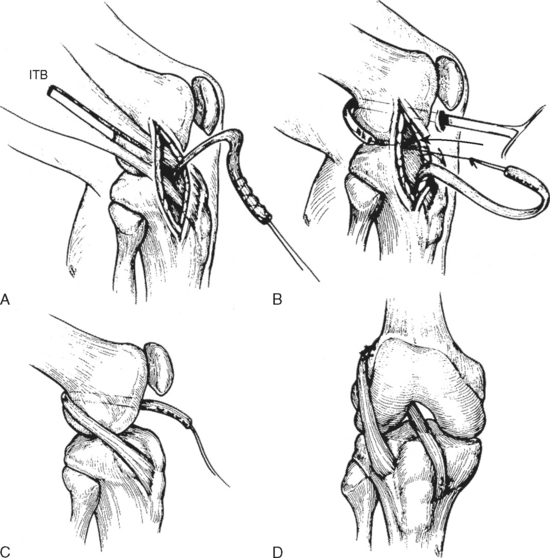

In an attempt to avoid crossing the physis with the graft, a number of grafts have been used with variations on a theme. The graft avoids the proximal tibial physis by using a drill hole in the proximal epiphysis only.35–37 In addition, the distal femoral physis is avoided by placing the graft in an “over-the-top” position through the posterior capsule35,37 or by a drill hole into the epiphysis only36 (Fig. 31-2). Only Level III and IV studies have documented the efficacy of these surgical treatments, with the longest follow-up being 5 years.35,36,38–43

A variation of the combined intra-articular and extra-articular reconstruction popularized by McIntosh and Darby has been proposed by Kocher37 in prepubescent skeletally immature children and adolescents to provide knee stability whereas at the same time avoiding the dreaded iatrogenic complication of growth disturbance seen with drill holes through either the proximal tibial or the distal femoral physis, or both (Level of Evidence IV) (Fig. 31-3).

In their Level IV study, 44 skeletally immature children (Tanner stage I or II) underwent the combined intra-articular and extra-articular reconstruction using iliotibial band. The factors evaluated were functional outcome, graft survival, and radiographic outcome with special emphasis on any growth disturbance. Follow-up period ranged from 2.0 to 15.1 years with a mean of 5.3 years. No growth disturbances were noted after the surgery as measured clinically and radiographically. Functional outcome was excellent with subjective knee scores of 96.7 ± 6.7 (range, 74–100) using the Lysholm knee score. Examination for stability of the knee revealed normal Lachman test results in 23 patients and near-normal results in 18 patients, whereas pivot shift examination was normal in 31 patients and near normal in 11 patients. Four patients who had undergone concurrent meniscal repair at the time of the ligamentous reconstruction (out of a total of 24 patients) underwent repeat meniscal surgery, either repair or partial resection.

Partial Physeal-Sparing Techniques.

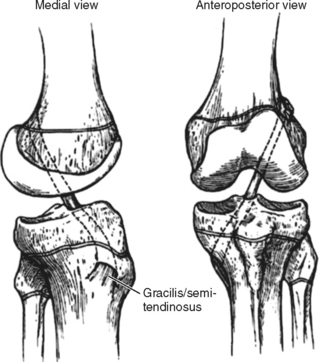

Partial physeal-sparing techniques use a small, central, and vertical drill hole through the proximal tibial physis and placement of the graft through the posterior capsule to an “over-the-top” position on the distal femur. Level IV studies indicate this technique renders the knee stable with little or no further meniscal damage, and no alteration of growth in either the distal femur or proximal tibia42,44, 45 (Fig. 31-4).

Transphyseal Reconstructions.

Transphyseal reconstructions use a 6- to 8-mm drill hole in the proximal tibia and distal femur. The drill holes are placed in as vertical orientation as possible to minimize the cross-sectional damage to the physes. The graft is placed in the same anatomic location as the native ACL (Figs. 31-5 and 31-6). A number of authors have concluded that transphyseal reconstructions are safe with no disruption of longitudinal growth (Fig. 31-7).

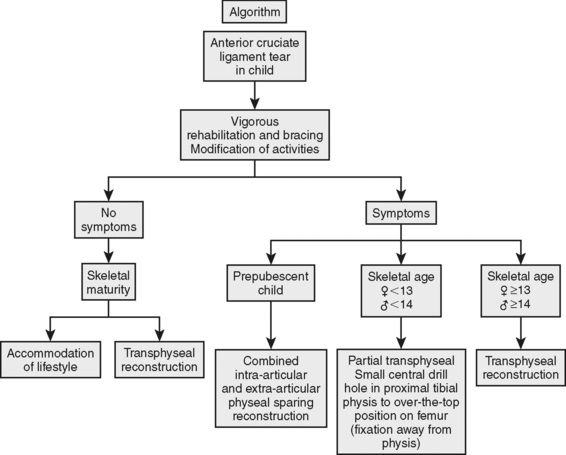

However, there are reports of growth disturbance utilizing a transphyseal reconstruction in children with open physes.34 Level II and III studies have documented that this reconstruction offers the benefits of long-term knee stability.5,46 In most cases, it should be reserved for the adolescent at or near the end of growth. Fig. 31-8 presents an algorithm for treatment of ACL tears in children.

POSTOPERATIVE REHABILITATION

Therapy consists of the use of a removable brace, although there is no evidence to suggest the outcome is any better, but it tends to restrict overzealous patients from too much activity (Level of Evidence V). The therapist works with the patient to decrease swelling, increase range of motion, and increase strength with closed chain exercises followed by proprioceptive training. At 3 months, jogging and sports-specific exercises are permitted with change of direction, cutting activities, and expected return to sports 6 months after the surgery.

In younger children with 3 or more years of growth remaining, there are 2 options. In prepubescent patients, a physeal-sparing technique should be used. Although not exactly replicating the anatomic location of the native ACL, studies suggest the efficacy of this treatment in controlling instability and preventing further intraarticular damage whereas at the same time not disrupting growth at either the distal femur or proximal tibia35–43 (grade C).

A strip of iliotibial band about 2 to 3 cm wide and 15 cm long is harvested, keeping the strip attached distally to Gerdy’s tubercle and detaching it proximally. Arthroscopy is performed, and the graft is passed in a retrograde fashion from an “over-the-top” position through the posterior capsule and intercondylar notch, underneath the intermeniscal ligament to a second incision on the proximal tibia. It is sutured to the periosteum distally to the proximal tibial physis after a small notch is placed in the proximal tibial epiphysis.37 The graft is first fixed on the femoral side at the insertion of the lateral intermuscular septum to the lateral femoral condyle with the knee flexed 90 degrees. It is then fixed under tension to the periosteum of the proximal tibia with the knee flexed 20 degrees.

In adolescent patients with approximately 2 years of growth remaining, partial transphyseal reconstructions are recommended. A small (6–8-mm) drill hole is placed in the proximal tibia in a more vertical orientation than is performed in skeletally mature individuals. Hamstring tendons (semitendinosus and gracilis) are used and are passed through the tibial tunnel and through the intercondylar notch and posterior capsule of the knee joint to an “over-the-top” position on the distal femur. A number of different fixation techniques have been used including staples and screws and washers for the distal femur fixation.42,44, 45

In the adolescent near skeletal maturity, the transphyseal method of reconstruction is safe and provides a stable knee. If the adolescent has 1 year or less of growth remaining, it is recommended to perform a transphyseal reconstruction of the ACL using autograft hamstring tendon, autograft bone-patellar tendon-bone, or allograft tendon (Achilles).5,46 The recommendations are summarized in the algorithm in Fig. 31-8 and in Table 31-1.

TABLE 31-1 Levels of Evidence for Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Skeletally Immature Individuals

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Angel KR, Hall DJ. Anterior cruciate ligament injury in children and adolescents. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:197-200.

2 Delee JC, Curtis R. Anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency in children. Clin Orthop. 1983;172:112-118.

3 Eskjaer S, Larsen ST. Arthroscopy of the knee in children. Acta Orthop Scand. 1987;58:273-276.

4 Graf BK, Lange RH, Frijisaki CK, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament tears in skeletally immature patients: Meniscal pathology at presentation and after attempted conservative treatment. Arthroscopy. 1992;8:229-233.

5 McCarroll JR, Rettig AC, Shelbourne KD. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the young athlete with open physes. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16:44-47.

6 Stanitski CL, Harvell JC, Fu F. Observations on acute knee hemarthrosis in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:506-510.

7 Steiner ME, Grana WA. The young athlete’s knee: Recent advances. Clin Sports Med. 1988;7:527-546.

8 Andrish JT. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in the skeletally immature patient. Am J Orthop. 2001;30:103-110.

9 Shea K, Pfeiffer R, Wang J, et al: ACL injury in pediatric and adolescent athletes: Differences between males and females. Presented at the Annual Meeting of Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America; Amelia Island, FL; May 2003.

10 Ireland ML. The female ACL: Why is it more prone to injury? Orthop Clin North Am. 2002;33:637-651.

11 Daniel DM, Stone ML, Dobson BE, et al. Fate of the ACL injured patient. A prospective outcome study. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:632-644.

12 Hawkins RJ, Misamore GW, Merritt TR. Follow-up of the acute nonoperated isolated anterior cruciate ligament tear. Am J Sports Med. 1986;14:205-210.

13 Buckley SL, Barrack RL, Alexander AH. The natural history of conservatively treated partial anterior cruciate tears. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17:221-225.

14 Aichroth PM, Patel DV, Zorrilla P. The natural history and treatment of rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament in children and adolescents. A prospective review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:618-619.

15 Janarv PM, Nystrom A, Werner S, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in skeletally immature patients. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:673-677.

16 Millett PJ, Willis AA, Warren RF. Associated injuries in pediatric and adolescent anterior cruciate ligament tears: Does a delay in treatment increase the risk of meniscal tear? Arthroscopy. 2002;18:955-999.

17 Mizuta H, Kubota K, Shiraishi M, et al. The conservative treatment of complete tears of the anterior cruciate ligament in skeletally immature patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:890-894.

18 Pressman AE, Letts RM, Jarvis JG. Anterior cruciate ligament tears in children: An analysis of operative versus non-operative treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:505-511.

19 Kannus P, Jarvinen M. Knee ligament injuries in adolescents. Eight year follow-up of conservative management. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:772-776.

20 Rang M. Children’s Fractures, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1983.

21 Kocher MS, Micheli LJ, Gerbino P, et al. Tibial eminence fractures in children: Prevalence of meniscal entrapment. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:404-407.

22 Kocher MS, Foreman ES, Micheli LJ. Laxity and functional outcome after arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation of displaced tibial spine fractures in children. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:1085-1090.

23 Kocher MS, Mandiga R, Klingele KE, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament injury versus tibial spine fracture in the skeletally immature knee: A comparison of skeletal maturation and notch width index. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:185-188.

24 Eiskjaer S, Larsen ST, Schmidt MB. The significance of hemarthrosis of the knee in children. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1988;107:96-98.

25 Kloeppel-Wirth S, Koltai JL, Dittmer H. Significance of arthroscopy in children with knee joint injuries. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1992;2:169-172.

26 Vahasarja V, Kinnuen P, Serlo W. Arthroscopy of the acute traumatic knee in children. Prospective study of 138 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:580-582.

27 Kocher MS, DiCanzio J, Zurakowski D, et al. Diagnostic performance of clinical examination and selective magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of intraarticular knee disorders in children and adolescents. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:292-296.

28 Luhmann SJ. Acute traumatic knee effusions in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:199-202.

29 Guzzanti V, Falciglia F, Gigante A, et al. The effects of intra-articular ACL reconstruction on the growth plate of rabbits. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:960-963.

30 Houle JB, Letts M, Yang J. Effects of tensioned tendon graft in a bone tunnel across the rabbit physis. Clin Orthop. 2001;391:275-281.

31 Edwards TB, Greene CC, Baratta RV, et al. The effect of placing a tensioned graft across open growth plates. A gross and histologic analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83A:725-734.

32 Lipscomb AB, Anderson AF. Tears of the anterior cruciate ligament in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:19-28.

33 Koman JD, Sanders JO. Valgus deformity after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament in a skeletally immature patient. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:711-715.

34 Kocher MS, Saxon HS, Hovis WD, et al. Management and complications of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in skeletally immature patients: Survey of the Herodicus Society and The ACL Study Group. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:452-457.

35 Parker AW, Drez D, Cooper JL. Anterior cruciate ligament injuries in patients with open physes. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:44-47.

36 Anderson AF. Transepiphyseal replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament in skeletally immature patients. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1255-1263.

37 Kocher MS. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the skeletally immature patient. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2006;14:124-134.

38 Vahasarja V, Kinnuen P, Serlo W. Arthroscopy of the acute traumatic knee in children. Prospective study of 138 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1993;64:580-582.

39 Brief LB. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction without drill holes. Arthroscopy. 1991;7:350-357.

40 DeLee J, Curtis R. Anterior cruciate ligament insufficiency in children. Clin Orthop. 1983;172:112-118.

41 Kim SH, Ha KI, Ahn JH, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in the young patient without violation of the epiphyseal plate. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:792-795.

42 Guzzanti V, Falciglia F, Stanitski CL. Physeal-sparing intraarticular anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in preadolescents. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:949-953.

43 Micheli LJ, Rask B, Gerberg L. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients who are prepubescent. Clin Orthop. 1999;364:40-47.

44 Lo IK, Kirkley A, Fowler PJ, et al. The outcome of operatively treated anterior cruciate ligament disruptions in the skeletally immature child. Arthroscopy. 1997;13:627-634.

45 Bisson LJ, Wickiewicz T, Levinson M, Warren R. ACL reconstruction in children with open physes. Orthopedics. 1998;21:659-663.

46 Aronowitz ER, Ganley TJ, Goode JR, et al. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in adolescents with open physes. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:168-175.