Chapter 71 What Is the Best Treatment for Ankle Osteochondral Lesions?

Osteochondral lesions (OCLs) are focal articular injuries of the subchondral bone and the cartilage with a multifaceted cause (trauma, ligament instability, ischemic necrosis, malalignment, endocrine diseases, and others). The knee and the ankle joint are the most commonly involved joints for OCLs in the lower extremity. In the ankle joint, OCLs are mostly seen in the talus, at the posteromedial and anterolateral talar dome, closely related to the top of the curvature. Talus OCLs most often affect sports active young individuals and becomes symptomatic through persistent pain, joint swelling, and sometimes blocking of the joint. OCLs are known to have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life and sports activity, or even their sports careers. In recent years, diagnosis of OCL increased substantially with the widespread use of modern diagnostic tools, such as computed tomography (CT), arthrocomputer tomography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)-CT, and other tools. With improved diagnostics, treatment options also changed. Currently, ankle arthroscopy allows beside direct diagnostic visualization and palpable assessment, as well as simultaneous minimally invasive osteochondral treatment (debridement, drilling, microfracturing, and others). Based on the severity and location of the disease, open surgery and extensive techniques might be applied (mosaicplasty, autologous chondrocytes implantation, and others). Despite the large number of publications (Level II-IV evidence), to date, no strong evidences and guidelines are available in the literature. The orthopedic surgeon has to choose the treatment of choice based on different variables, such as age, size, location of the OCLs, and other factors.

DEFINITION, STAGING, CLINICS

OCLs are articular injuries of the subchondral bone and the overlaying cartilage. Because of the still unclear natural history of OCLs, several terms can be found for this entity to date in the literature, for example, osteochondritis dissecans, osteochondral fracture, flake fracture, and others. Because currently there is no proof for an underlying inflammation, the traditional term osteochondritis dissecans introduced by König1 in 1888 should be abandoned. Furthermore, the term transchondral/osteochondral/flake fracture may be meaningful only in traumatic cases. To include all these causes and others, for example, idiopathic osteonecrosis, the term osteochondral lesions (OCLs) provides the most cautious terminology.

The traditional staging system for OCLs of the talus is the Berndt and Harty2 classification based on radiographic findings. This classification consists of the following stages of an osteochondral talus fragment: stage I, small compression area; stage II, incomplete avulsion of a fragment; stage III, complete avulsion without displacement; and stage IV, avulsed fragment displaced within the joint. The Berndt and Harty classification has the advantage of being popular, but it does not accurately reflect the integrity of the articular cartilage. The Ferkel and Sgaglione3 classification is a CT-based classification describing fragmentation, osteonecrosis, and cyst formations (stage I-IV). Anderson and colleagues4 described an MRI-based classification including the bone marrow edema. Last, a commonly used arthroscopic classification is the OCL classification of the International Cartilage Repair Society.5

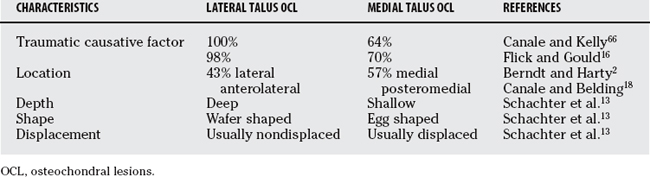

Epidemiologically, the ankle registers 4% of all the human osteochondral defects.6 The cause of OCLs of the talus has multiple facets. However, it can be subdivided into a traumatic and nontraumatic cause. Trauma plays the most important role in the pathomechanism of talus OCLs. Overall, more than 80% of the talus OCLs are of traumatic origin.7,8 In such traumatic cases, the acute OCLs are frequently located on the lateral dome of the talus (anterolateral) (Table 71-1). Hereby, the most common reasons are a severe inversion ankle sprain, chronic ankle instability (CAI; causing in 5–9% of the cases a lateral talar OCL),9,10 or a fracture mechanism. However, medial lesions are more common than lateral OCLs. In these cases, the most affected area is the posteromedial talar dome (see Table 71-1). On the basis of repetitive microtraumas, avascular necrosis, genetics, endocrinic reasons, or systemic reasons, the nontraumatic causative agent with osteonecrosis represents to date still an unclear pathomechanism of chronic OCLs (longer than 2 months). Here, one should be alert on not missing a radiologically correlating hindfoot malalignment (hindfoot varus or valgus) that could explain the overload on the painful OCL joint region. In many cases, a causative agent cannot be traced and remains “idiopathic.”

An untreated OCL represents a local osteoarthritis model because of the altered joint biomechanics. Hereby, a traumatic osteochondral defect (flake fracture) or pathologic chronic shear forces (CAI11) cause damage of the superficial layer of the cartilage, and with time deep cracks and degeneration of the cartilage. Subsequently, joint fluid pumps into the subchondral bone and creates painful cysts and large-area cartilage lifting. At the end, OCL fragments can break off and dislocate all over the joint.

Patients with OCLs of the talus typically report chronic ankle pain, joint stiffness, ankle swelling, snapping, giving way, and weakness. The patients, usually of young age (mean age in a meta-analysis on 734 patients, 26.9 years),12 are substantially limited in their daily life, in their sports activities, and have a reduced sports level. Many of them lose their sports career or even jobs by disability.

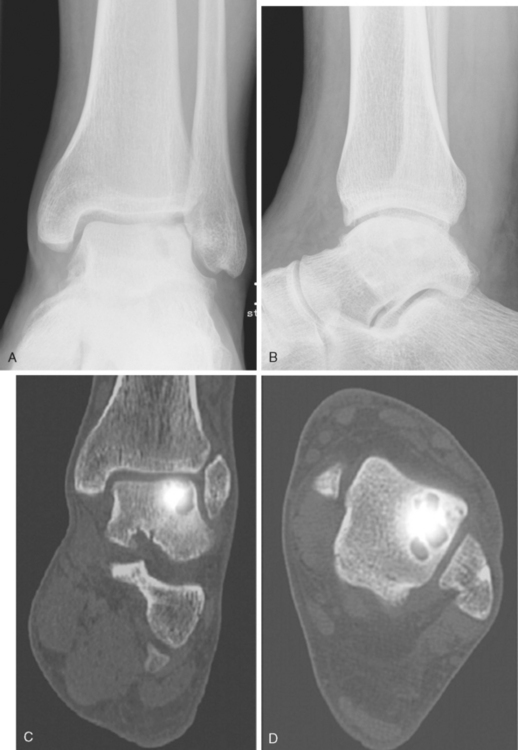

With CT, the stages described by Berndt and Harty can be better defined, OCL cysts and fragments better visualized, and the integrity of the subchondral bone better analyzed. The CT scan is therefore a valuable diagnostic for preoperative planning. MRI provides complementary information, for example, the status of the OCL overlaying cartilage, information on bony edema, and the situation of the ligaments. Scintigraphy showed to be useful in evaluating OCLs when radiographs appear to be normal.4,13 Addressing the lack of anatomic accuracy of the classic scintigraphy, a new diagnostic tool for OCLs emerged: the SPECT-CT. The SPECT-CT combines data of the scintigraphy and CT scan and fuses it to one picture: SPECT providing the activity and metabolic rate of the OCL surrounding bone, and the CT the precise anatomic localization (Fig. 71-1). Lastly, diagnostic ankle arthroscopy remains a reliable diagnostic tool, allowing direct and dynamic examination of the talus OCLs and the ankle-stabilizing ligaments.14

TREATMENT OPTIONS

The conservative treatment of OCLs of the talus is limited for stages I and II only. Success rates for nonoperative treatment with sports restriction and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or cast immobilization differ from 0% to 100% (review article12). A meta-analysis on 201 patients proved a 45% success rate of conservative treatment for stages I and II, as well as medial stage III talus OCLs.15 Whereas acute lesions seem to do worse (0% success rates in acute transchondral fractures16), chronic lesions show different success rates between 41% (cast immobilization12) and 59% for restriction of activities, but free range of motion.17,18 Young patients seem to do better with conservative treatment than aged patients. Bruns and Rosenbach19 showed 85% excellent and good results in patients 16 years and younger in comparison with 65% in adults, with 8% failure in each group only (Level IV evidence).19 These results are also confirmed by Higuera and coworkers (Level IV).20 In long-term, persistent, radiologic irregularities were found in 38% (Level IV).21 Shearer and coworkers22 managed even high-grade cystic lesions nonsurgically (Level IV).22 However, after 38 months of follow-up, 18% of patients had to be transferred to ankle arthrodesis.

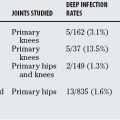

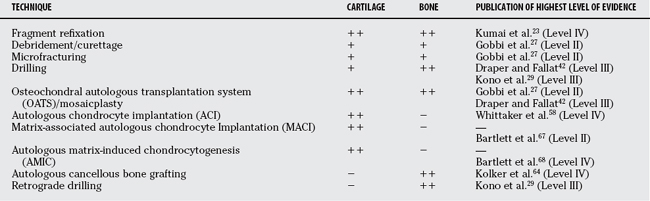

In most of the conservatively treated OCL cases, the pain remains untreated and the disease advances to further stages. Berndt and Harty2 reported in 1959 that nonoperatively treated patients obtained poor results, and that good results were registered in 84% of the cases after surgical treatment (Level IV). Surgical treatment of OCLs traditionally includes excision of loose bodies, debridement of the area, and drilling or microfracturing. This surgery may be performed open or arthroscopically. The arthrotomy may sometimes require a medial or lateral malleolar osteotomy, grooving of the anteromedial distal tibia, or an osteotomy of the anterolateral tibia to reach the involved OCL talus region. As an alternative or as an addition to the open technique, ankle arthroscopy allows, beside a good diagnostic visualization of the OCLs, a minimal invasive therapy avoiding the high morbidity of an extensive arthrotomy or malleolar osteotomy. The treatment of OCLs of the talus includes a primary (as fixation of a flake fracture in traumatic cases) or a secondary repair (surgical treatment of chronic OCLs). The different options for secondary repairs depend on whether the OCL is predominantly a problem of the chondral layer, the osseous part, or a combination of both, on the age of the patient and the size of the OCL (Tables 71-2 and 71-3).

TABLE 71-2 Treatment Options for Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus with Tissue Repair Potential (Cartilage and Bone)

TABLE 71-3 Surgical Principles of Osteochondral Lesions of the Talus

| TECHNIQUE | REFERENCES | |

|---|---|---|

| OCL Stage | ||

| Berndt and Harty stages I and II | ||

ACI, autologous chondrocyte implantation; AMIC, autologous membrane-induced chondrogenesis; MACI, matrix-membrane autologous chondrocyte implantation; OATS, osteochondral autograft transfer system; OCL, osteochondral lesions; TAR, total ankle replacement.

Primary Fixation of Acute Osteochondral Lesions

In case of an osteochondral fracture of the talus, the fragment can be fixed by low-profile screws, bioabsorbable materials, or other methods, for example, cortical bone peg fixation (89% success rate)23 or fibrin fixation (75% success rate).24 With this therapy, about 73% of the patients reach a satisfactory result12,23 (all evidence Level IV).

Debridement, Abrasion

With the debridement, the surgeon removes the necrotic tissue and loose bodies by excision and curettage. Excision and curettage (76% overall success rate) in combination show better results than excision alone (38% overall success rate).12 With the simultaneous lavage, catabolic enzymes and inflammation mediators are also removed. This surgical option is adequate only for small OCL and gives only good results on a short-term basis. Hereby, arthroscopic results seem to be slightly better in comparison with open procedures12,25, 26 (all Level IV evidence). Surprisingly, the only Level of Evidence II study on OCL treatment, reported by Gobbi and coauthors,27 describes arthroscopic excision and shaving to show no significant difference to microfracture and osteochondral autograft trans-fer system (OATS) in 33 patients after 12 and 24 months.

Retrograde Drilling

Retrograde drilling is reserved for stage I and II of the talus OCLs. Hereby, the sclerotic subchondral bone of the OCL cysts are minimally invasive opened up and filled with autologous spongiotic bone (as, for example, from the iliac crest) or osteoinductive and osteoconductive materials. This technique allows an ingrowing of marrow cells and blood vessels to build a healthy, stable subchondral bone and overlying fibrocartilaginous tissue. Retrograde drilling showed an 81% success rate by drilling through the sinus tarsi (Level IV).28

Kono and researchers29 showed that in Pritsch O or I classified OCL (grade O: cartilage layer intact; grade I: cartilage soft, but stable in place), retrograde drilling reaches significantly better results than transmalleolar (anterograde) drilling (Level III).

Microfracturing

With microfracturing, the sclerotic subchondral bone is removed and the OCL area is multiply microfractured or alternatively microdrilled. Steadman and colleagues30 first described the technique of microfracturing. Through the created bony holes, bone-marrow stem cells are expected to nest on the fibrin clot in the OCL defect and develop into chondroblasts, chondrocytes, and fibroblast, which produce a nonhyaline fibrocartilaginous matrix. However, fibrocartilage is known to have a pathologic viscoelastic property.31 One limitation of microfracturing is the use only for cartilage defect smaller than 1.5 cm2 and with a maximal depth of 7 mm (see Table 71-3).32

Currently, microfracturing of the talus has demonstrated good or excellent results,6,33 with success rates of 77% to 96%34,35 (all Level IV evidence). Saxena and Eakin34 showed a significant shorter recovery time for microfracture in comparison with autogenous bone grafting (Level IV). Becher and Thermann35 showed that after microfracturing in follow-up arthroscopies, the cartilage cannot be distinguished from the surrounding cartilage (Level IV).

Anterograde drilling, arthroscopically, percutaneous, or transmalleolar performed, shows in combination with excision and curettage better results than excision and curettage alone7,16,36–40 (all Level IV), with success rates in a meta-analysis of 76% and 87%, respectively.12 Angermann and Jensen25 found in a follow-up of 9 to 15 years that only 1 of 18 patients had new signs of osteoarthritis (Level IV).

Osteochondral Autograft Transfer System

The OATS or mosaicplasty technique is based on harvesting full-thickness osteochondral grafts from a donor site such as the lateral supracondylar or the intercondylar notch area of the femur. This technique is indicated for grades III and IV of substantially large OCL defects of the talus. The reported results are believed to be good to excellent (Level IV).41 However, the donor-site morbidity of knee-to-talus mosaicplasty is not negligible, and the cartilage properties of knee and talus are known to not biomechanically and biochemically match together.6 Furthermore, with OATS, the precise restoration of the curvature and congruency of the talus is technically demanding. Gobbi and coauthors27 (Level II) and Draper and Fallat42 (Level III) showed that OATS and microfracturing/drilling show no significant differences in follow-up. Success rates of 89 to 100% are published (all Level IV).43–50 Kreuz and investigators51 showed that OATS offers a successful opportunity in OCL revisions (Level IV). Only recently were concerns about donor-site morbidity reported.52

Osteochondral Allograft Transplantation

The transplantation of an osteochondral allograft is indicated for large OCLs of the talus. In a long-term prospective study, Gross and colleagues53 confirmed the value of fresh osteochondral allografts to reconstruct articular defects of joints in young active patients (knee joint study; Level II; success rate of 85% for femur and 80% for tibial plateau). Unlike for the knee, few reports are available for osteochondral allograft talus reconstruction in the literature (all evidence Level IV).54–56 Gross and colleagues54 report a 66% survivorship rate of talus osteochondral allografts after 11 years (Level IV).

Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation

The principle of autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) is based on harvesting of autologous chondrocytes (knee, talus, detached OCL fragment), culturing of the cells in vitro for 2 to 5 weeks, and finally reimplantation of the proliferated cells. This technique was first described in knee OCLs57 and also is currently used in talus OCLs successfully.32 Whittaker and coworkers58 report 90% good and excellent results and in rearthroscopies lesions completely disappeared (Level IV). Koulalis and coauthors59 even report success in 100% of cases (Level IV). The ACI can be implanted under a periosteal flap (ACI), in a matrix-membrane, or under a collagen membrane cover. These chondrocyte transplantation techniques are indicated in large defects of OCL stages III and IV with cystic formations or failed previous surgery (after debridement, drilling, etc.). The defect should be greater than 1.5 cm2, and the age of the patients is limited to younger than 55 years.6,60 Kissing talus-tibia lesions and osteoarthritis are contraindications for ACI. In cases of larger bone defects, ACI can be used together with debridement and bone grafting. In cases of hindfoot malalignment and CAI, additional surgeries (osteotomies, ligament repair, etc.) should be added at the time of ACI surgery for restoration of normal ankle biomechanics. The first mid-term results of ACI are promising (Level IV).32 ACI techniques, however, produce hyaline-like cartilage only. Furthermore, the duration of recovery and the treatment costs are substantially longer and greater compared with other methods.

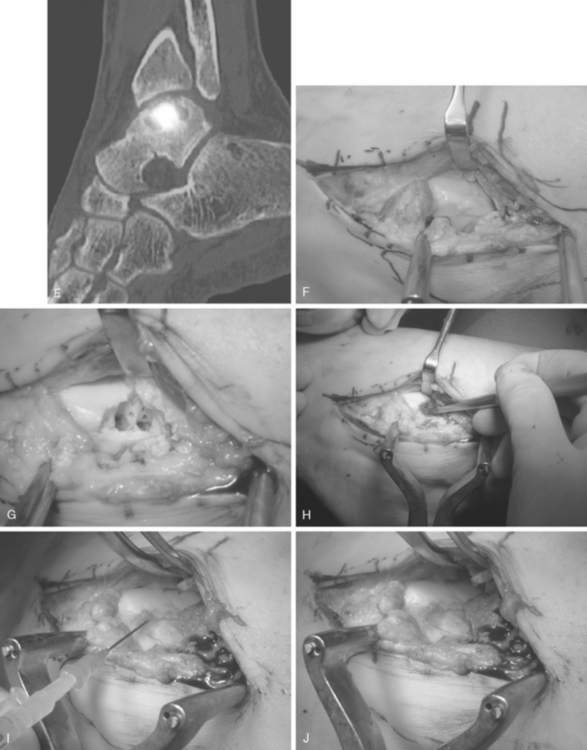

A new method for autologous chondrocyte regeneration is the so-called autologous membraneinduced chondrogenesis (AMIC; see Table 71-2; see Fig. 71-1). The AMIC technique is a one-stage procedure consisting of debridement, microfracturing, or drilling (without or with bone transplantation), and coverage of the treated area by a bilayer collagen membrane that is fixed to the site by fibrin glue (see Fig. 71-1).

SUMMARY

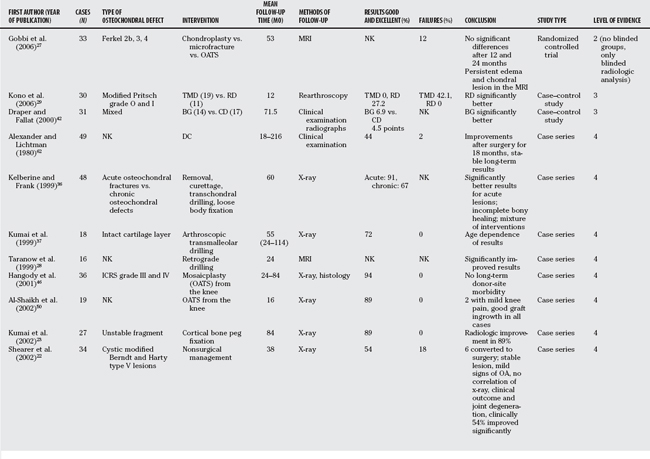

In summary, based on the diagnostic tools (x-ray, CT, MRI, scintigraphy, SPECT-CT, arthroscopy) specifically used in the different publications, currently, several classifications are available for talus OCLs. Because OCLs of the talus have multiple causative factors and still an unclear pathomechanism and natural history, no classification so far has managed to provide satisfactory evidence for a proper therapeutic principle and outcome prediction. Despite the large number of publications, the evidence for treatment of OCL of the talus is still poor. To our knowledge, no publication to date shows Level I evidence for specific treatments. Only few publications show Level II and III evidence (Table 71-4) with small cohorts and, therefore, low scientific power. The majority of the articles published on talus OCL state Level IV evidence (see Table 71-4). Accurate description of the causative factor, size, location of OCL lesions, and exact treatment and after-treatment are not provided in the majority of the studies. The indications for nonoperative and operative treatment of OCL of the talus are still quite controversial. Only a few treatment tendencies do crystallize out. A few variables, such as stage, size, location, tissue involved (cartilage/bone), and chronicity of the OCL lesion, as well as the age of the patient, are decisive for the treatment of choice and best outcome (see Tables 71-2 and 71-3). Most of the authors and reports recommend as a first attempt nonoperative treatment with non–weight bearing or immobilization, or both; this provides good results in patients especially of young age and those with stage I and II talus OCLs. In case of lack of pain relief after 1 year of conservative treatment or in cases with stage III and IV talus, OCL surgical treatment is indicated. Hereby a few rules can be followed based on a few variables: involved tissue (cartilage, bone; see Table 71-2), as well as OCL stage, OCL size, and patient age (see Table 71-3).

GUIDELINES

Currently, few review articles provide the best guidelines for treatment of OCL of the talus.12,13, 15, 61 Guidelines and algorithms are also presented yearly in symposia and instructional courses of several societies, such as American Foot and Ankle Society, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, ICRS, and others. The current valid guidelines are summarized in this chapter.

Based on the actual evidence of the literature and our own clinical experience, we recommend following the therapeutic principles described in this chapter, specifically in Tables 71-2 and 71-3. In general, early grades of OCL (stage I or II) may be treated by conservative treatment first; more severe grades of OCL (stage III or IV) or failures of conservatively managed stage I or II OCL need a surgical approach. Because the half-life of the published talus OCL articles is short, and new publications and treatment modifications emerge almost monthly, we recommend acquiring continuing education through high evidence level articles, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and specific high-quality symposia and courses. Table 71-5 provides a summary of recommendations.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCE |

|---|---|---|

1 König F. On the presence of loose bodies in joints. Deutsche Zeitschrift für Chirurgie. 1888;27:90-109.

2 Berndt AL, Harty M. Transchondral fractures (osteochondritis dissecans) of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1959;41-A:988-1020.

3 Ferkel RD, Sgaglione NA, DelPizzo W. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus: Long-term results. Orthop Trans. 1990;14:172-173.

4 Anderson IF, Crichton KJ, Grattan-Smith T, et al. Osteochondral fractures of the dome of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1143-1152.

5 Mainil-Varlet P, Aigner T, Brittberg M, et al. Histological assessment of cartilage repair: A report by the Histology Endpoint Committee of the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(suppl 2):45-57.

6 Zengerink M, Szerb I, Hangody L, et al. Current concepts: Treatment of osteochondral ankle defects. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:331-359. vi

7 Pritsch M, Horoshovski H, Farine I. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:862-865.

8 Chin TW, Mitra AK, Lim GH, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesion of the talus. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1996;25:236-240.

9 Bosien WR, Staples OS, Russell SW. Residual disability following acute ankle sprains. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37-A:1237-1243.

10 Lippert MJ, Hawe W, Bernett P. [Surgical therapy of fibular capsule-ligament rupture]. Sportverletz Sportschaden. 1989;3:6-13.

11 Schimmer RC, Dick W, Hintermann B. The role of ankle arthroscopy in the treatment strategies of osteochondritis dissecans lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:895-900.

12 Verhagen RA, Struijs PA, Bossuyt PM, van Dijk CN. Systematic review of treatment strategies for osteochondral defects of the talar dome. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8:233-242.

13 Schachter AK, Chen AL, Reddy PD, Tejwani NC. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:152-158.

14 Hintermann B, Boss A, Schafer D. Arthroscopic findings in patients with chronic ankle instability. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:402-409.

15 Tol JL, Struijs PA, Bossuyt PM, et al. Treatment strategies in osteochondral defects of the talar dome: A systematic review. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:119-126.

16 Flick AB, Gould N. Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus (transchondral fractures of the talus): Review of the literature and new surgical approach for medial dome lesions. Foot Ankle. 1985;5:165-185.

17 Huylebroek JF, Martens M, Simon JP. Transchondral talar dome fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1985;104:238-241.

18 Canale ST, Belding RH. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:97-102.

19 Bruns J, Rosenbach B. Osteochondrosis dissecans of the talus. Comparison of results of surgical treatment in adolescents and adults. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1992;112:23-27.

20 Higuera J, Laguna R, Peral M, et al. Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus during childhood and adolescence. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:328-332.

21 Wester JU, Jensen IE, Rasmussen F, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the talar dome in children. A 24 (7-36) year follow-up of 13 cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65:110-112.

22 Shearer C, Loomer R, Clement D. Nonoperatively managed stage 5 osteochondral talar lesions. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:651-654.

23 Kumai T, Takakura Y, Kitada C, et al. Fixation of osteochondral lesions of the talus using cortical bone pegs. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:369-374.

24 Angermann P, Riegels-Nielsen P. Fibrin fixation of osteochondral talar fracture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:551-553.

25 Angermann P, Jensen P. Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus: Long-term results of surgical treatment. Foot Ankle. 1989;10:161-163.

26 Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Sarrosa EA. Arthroscopic treatment after previous failed open surgery for osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:809-812.

27 Gobbi A, Francisco RA, Lubowitz JH, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: Randomized controlled trial comparing chondroplasty, microfracture, and osteochondral autograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1085-1092.

28 Taranow WS, Bisignani GA, Towers JD, Conti SF. Retrograde drilling of osteochondral lesions of the medial talar dome. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:474-480.

29 Kono M, Takao M, Naito K, et al. Retrograde drilling for osteochondral lesions of the talar dome. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1450-1456.

30 Steadman JR, Rodkey WG, Rodrigo JJ. Microfracture: Surgical technique and rehabilitation to treat chondral defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 391 suppl; 2001; S362-S369.

31 Peterson L, Brittberg M, Kiviranta I, et al. Autologous chondrocyte transplantation. Biomechanics and long-term durability. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:2-12.

32 Giannini S, Vannini F. Operative treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talar dome: Current concepts review. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25:168-175.

33 Thermann H, Becher C. [Microfracture technique for treatment of osteochondral and degenerative chondral lesions of the talus. 2-year results of a prospective study]. Unfallchirurg. 2004;107:27-32.

34 Saxena A, Eakin C. Articular talar injuries in athletes: Results of microfracture and autogenous bone graft. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:1680-1687.

35 Becher C, Thermann H. Results of microfracture in the treatment of articular cartilage defects of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:583-589.

36 Kelberine F, Frank A. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talar dome: A retrospective study of 48 cases. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:77-84.

37 Kumai T, Takakura Y, Higashiyama I, Tamai S. Arthroscopic drilling for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:1229-1235.

38 Lahm A, Erggelet C, Steinwachs M, Reichelt A. Arthroscopic management of osteochondral lesions of the talus: Results of drilling and usefulness of magnetic resonance imaging before and after treatment. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:299-304.

39 Loomer R, Fisher C, Lloyd-Smith R, et al. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:13-19.

40 Schuman L, Struijs PA, van Dijk CN. Arthroscopic treatment for osteochondral defects of the talus. Results at follow-up at 2 to 11 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:364-368.

41 Hangody L, Kish G, Karpati Z, et al. Treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the talus: Use of the mosaicplasty technique—a preliminary report. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18:628-634.

42 Draper SD, Fallat LM. Autogenous bone grafting for the treatment of talar dome lesions. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2000;39:15-23.

43 Scranton PEJr, Frey CC, Feder KS. Outcome of osteochondral autograft transplantation for type-V cystic osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:614-619.

44 Sammarco GJ, Makwana NK. Treatment of talar osteochondral lesions using local osteochondral graft. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:693-698.

45 Lee CH, Chao KH, Huang GS, Wu SS. Osteochondral autografts for osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:815-822.

46 Hangody L, Kish G, Modis L, et al. Mosaicplasty for the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans of the talus: Two to seven year results in 36 patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:552-558.

47 Gautier E, Kolker D, Jakob RP. Treatment of cartilage defects of the talus by autologous osteochondral grafts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:237-244.

48 Baums MH, Heidrich G, Schultz W, et al. Autologous chondrocyte transplantation for treating cartilage defects of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:303-308.

49 Baltzer AW, Arnold JP. Bone-cartilage transplantation from the ipsilateral knee for chondral lesions of the talus. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:159-166.

50 Al-Shaikh RA, Chou LB, Mann JA, et al. Autologous osteochondral grafting for talar cartilage defects. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:381-389.

51 Kreuz PC, Steinwachs M, Erggelet C, et al. Mosaicplasty with autogenous talar autograft for osteochondral lesions of the talus after failed primary arthroscopic management: A prospective study with a 4-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:55-63.

52 Reddy S, Pedowitz DI, Parekh SG, et al. The morbidity associated with osteochondral harvest from asymptomatic knees for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35:80-85.

53 Gross AE, Shasha N, Aubin P. Long-term followup of the use of fresh osteochondral allografts for posttraumatic knee defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 435; 2005; 79-87.

54 Gross AE, Agnidis Z, Hutchison CR. Osteochondral defects of the talus treated with fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:385-391.

55 Kim CW, Jamali A, Tontz WJr, et al. Treatment of post-traumatic ankle arthrosis with bipolar tibiotalar osteochondral shell allografts. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:1091-1102.

56 Rodriguez EG, Hall JP, Smith RL, et al. Treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus with cryopreserved talar allograft and ankle distraction with external fixation. Surg Technol Int. 2006;15:282-288.

57 Brittberg M, Lindahl A, Nilsson A, et al. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:889-895.

58 Whittaker JP, Smith G, Makwana N, et al. Early results of autologous chondrocyte implantation in the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:179-183.

59 Koulalis D, Schultz W, Heyden M. Autologous chondrocyte transplantation for osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 395; 2002; 186-192.

60 Martin JA, Buckwalter JA. Aging, articular cartilage chondrocyte senescence and osteoarthritis. Biogerontology. 2002;3:257-264.

61 Giannini S, Buda R, Faldini C, et al. Surgical treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus in young active patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(suppl 2):28-41.

62 Alexander AH, Lichtman DM. Surgical treatment of transchondral talar-dome fractures (osteochondritis dissecans). Long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62:646-652.

63 Robinson DE, Winson IG, Harries WJ, Kelly AJ. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:989-993.

64 Kolker D, Murray M, Wilson M. Osteochondral defects of the talus treated with autologous bone grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:521-526.

65 Han SH, Lee JW, Lee DY, Kang ES. Radiographic changes and clinical results of osteochondral defects of the talus with and without subchondral cysts. Foot Ankle Int. 2006;27:1109-1114.

66 Canale ST, Kelly FBJr. Fractures of the neck of the talus. Long-term evaluation of seventy-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:143-156.

67 Bartlett W, Skinner JA, Gooding CR, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation versus Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation for osteochondral defects of the knee: A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:640-645.

68 Bartlett W, Gooding CR, Carrington RW, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation at the knee using a bilayer collagen membrane with bone graft. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:330-332.