Chapter 69 What Is the Best Treatment for Achilles Tendon Rupture?

Achilles tendon ruptures (Fig. 69-1) are a catastrophic event that occurs when forces that are placed on the Achilles tendon exceed its tensile limits (approximately strain >8%).1 This event is likely a result of a preexisting Achilles tendon disease2–4 if the forces are relatively low. The histopathology of the diseased human Achilles tendon has been previously described on the basis of biopsies from the Achilles tendons of patients with subcutaneous rupture3,5–9 and chronic, localized Achilles tendon symptoms.6,10, 11 These studies suggest that a common pathologic process may predispose individuals to rupture.3,6

The most common patient profile for human Achilles tendon rupture would be that of a man in his third or fourth decade of life who plays sports occasionally. Men-to-women rupture ratios have been reported from 2:1 to 12:1.2,4, 12 The mean age has been estimated between the 30s and 40s,13 with the left Achilles rupture more common than the right probably reflecting right-side dominance with left leg pushing off.14 Leppilahti and colleagues13 report on an increasing incidence of rupture in 1994 in Oulu, Finland, to be 18 per 100,000, whereas Suchak and coworkers15 report the incidence to be between 5.5 and 9.9 ruptures per 100,000 in North America. Subjects have been participating in sports during rupture at rates from 44.4% to 83%,16,17 with 52.3% of ruptures playing badminton. The site of rupture has been reported to occur in the myotendinous junction in 12.1%, the insertion in 4.6%, and 3.5 cm proximal to the insertion in 83% of patients.4

TREATMENT

Operative versus Nonoperative Treatment

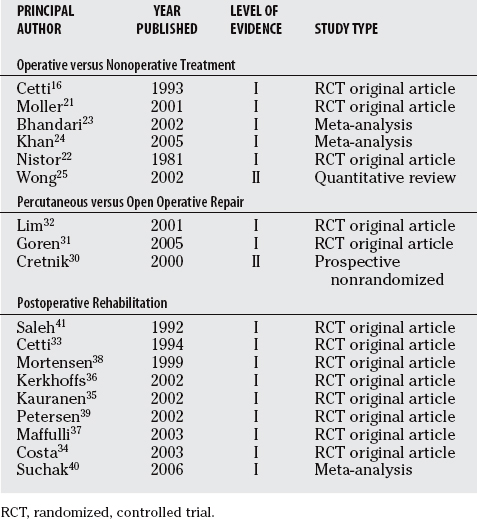

In an attempt to gather the best evidence available to guide treatment recommendations for Achilles tendon rupture, a literature search was performed using the search terms “Achilles,” “tendon,” “rupture,” “treatment,” “operative,” and “nonoperative.” Literature was then screened for Level I and II evidence comparing operative and nonoperative treatments of Achilles tendon ruptures. The search was narrowed to six studies (Table 69-1).

TABLE 69-1 Summary of the Evidence Available That Should be Considered When Choosing Treatment Options for a Ruptured Achilles Tendon

Three of the studies meet the criteria for Level 1 original evidence articles including randomized, control trials (RCT) by Cetti and investigators,16 Moller and researchers,21 and Nistor.22 Cetti and investigators16 randomized 111 healthy subjects, of which 90% were reported to regularly participate in sports, to operative repair (n = 56) or nonoperative treatment (n = 55) of their ruptured Achilles tendons. This study cites a rerupture rate of 5.4% and 14.5% for operative and nonoperative cohorts, respectively. The deep infection rate was 3.6% and 0% in favor of the nonoperative cohort. Furthermore, many complications rates were cited to be lower in the nonoperative group, as was the return to sport rate.

In the second Level I study, Moller and researchers21 cite similar results with a rupture rate of 1.7% versus 20.8% in the operative and nonoperative cohorts, respectfully. This study also cites decreased complications with a slower return to work time in the patients treated without surgery. The patients in both cohorts had similar demographic characteristics and were healthy, reporting a high level (70–80%) of regular participation in sports.

In the third Level I original evidence article, Nistor22 randomized 115 patients of similar health demographic characteristics to operative repair or nonoperative treatment of their ruptured Achilles tendon. Results reported included a 3% rerupture rate for both operative and nonoperative treatments, whereas the infection rate was 4.4% and 0% favoring nonoperative treatment. The minor complication rate was much greater (68.8% vs. 0%) in the nonoperative group.

The final three studies reviewed included Level I meta-analysis studies by Bhandari and colleagues23 and Khan and coauthors,24 and a Level II quantitative review of the literature by Wong and coauthors.25 The most recent study by Khan combined the results of four studies,16,21, 22, 26 which included 356 patients. The cumulative rerupture rate was greater (12.6% vs. 4.6%) in the nonoperative group, but the infection (4.0% vs. 0%) and minor complication rates (33.5% vs. 2.7%) were lower.

In Bhandari and colleagues’23 Level I meta-analysis study, six original articles were identified to meet all eligibility criteria.16,21,22,27–29 The cumulative rerupture rate was greater in the nonoperative group (13% vs. 3.1%; n = 448; P = 0.005), but the infection rate was lower (0% vs. 4.7%; n = 421; P = 0.03). No difference was cited in the return to function and the spontaneous complaints cumulative data.

Finally, Wong and coauthors’25 quantitative review of the literature pooled data gathered from 125 articles including 5370 patients. This study identifies no difference in the rerupture rate between operative and nonoperative cohorts (1.4% vs. 1.5%) but does cite an increased wound complication rate in the operative cohort (14.6% vs. 0.5 %).

Percutaneous versus Open Operative Repair

A literature search was performed using the search terms “Achilles,” “tendon,” “rupture,” “treatment,” and “operative,” “open,” “percutaneous,” and “surgery.” Literature was then screened for Level I and II evidence comparing percutaneous and open operative treatments of Achilles tendon ruptures; three studies were found30–32 (see Table 69-1).

The best article currently available is a Level I RCT with a patient population of 66 (33 patients in each of the open and percutaneous cohorts) by Lim and coauthors.32 Patients in these cohorts were described as more sedentary (30% regular participation in sports) with no information on health status. Results cited a lower rerupture rate in patients treated with percutaneous repair versus open repair (6% vs. 2%); however, the differences in these results were not statistically significant. However, a statistically significant increase in the infection rate for patients treated with open repair (21% vs. 0%) was reported. Sural nerve complications, adhesions, and perceived functional outcomes were greater in the percutaneous repair, although again they were not statistically significant.

The second Level I study by Goren and researchers31 was an RCT comparing isokinetic strength and range of motion after percutaneous (n = 10) and open (n = 10) surgical repair of a ruptured Achilles tendon. The study cites no difference in health status of the two cohorts. Results indicate that isokinetic strength and range of motion were equal in the two cohorts; however, there was an increased incidence of Sural nerve injury (40% vs. 0%) in the percutaneous-treated cohort.

Cretnik and colleagues’30 Level II, prospective, nonrandomized study compares 237 patients with an Achilles tendon rupture treated with open (n = 105) versus percutaneous (n = 132) surgical repair. The results revealed slight increases in rerupture (3.7% vs. 2.8 %) and sural nerve injury (4.5% vs. 2.8%) rates in the percutaneous cohorts, but these differences were not statistically significant. However, fewer major (4.5% vs. 12.4%) and total complications (9.7% vs. 21%) were reported in the percutaneous cohort. Functional assessment using Foot and Ankle society score and the Holtz score demonstrated no differences between the two cohorts.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

A literature search was undertaken to compare postoperative rehabilitation methods for treatment outcomes of patients with cast immobilization versus “functional rehabilitation” using the search terms “Achilles,” “tendon,” “rupture,” “treatment,” “operative,” “cast,” “immobilization,” “rehabilitation,” “functional,” and “postoperative.” Literature was then screened for Level I and II evidence, identifying nine articles33–40 (see Table 69-1). Eight Level 1 original articles were RCTs, which were all in favor of early functional rehabilitation when compared with more traditional means of cast immobilization. The ninth article was a Level I meta-analysis pooling the results of six of the above articles.

Cetti and colleagues’33 article was the first Level I article to compare the outcomes of patients using a mobile cast (n = 30) versus a rigid below-knee cast (n = 30). No significant difference in rerupture and infection rates was found in the two cohorts, but the mobile cast cohort was reported to have fewer minor complications, improved functional outcome, less elongation of the tendon, and was more likely to return to work.

Saleh and investigators41 report results from a Level I study of functional rehabilitation with a full weight-bearing brace that holds the foot in 15 degrees of plantar flexion. The authors report a more rapid return of ankle dorsiflexion and return to normal activities.

Mortensen and researchers’38 Level I study randomized 71 patients with an acute Achilles rupture to either cast immobilization for 8 weeks or early restricted motion of the ankle in a below-the-knee brace for 6 weeks. They also found that the increased motion cohort had improved functional outcome with respect to range of motion and a quicker return to sports or work.

Kerkhoffs and coworkers’36 Level I study randomized a total of 39 consecutive patients with complete ruptures of the Achilles tendon to a walking cast or a wrap and showed that the wrap cohort allowed a significantly shorter hospital stay, as well as return to preinjury sports level compared with treatment with a walking cast. No increased risk of rerupture or wound healing problems were reported.

Costa and colleagues’34 Level I study randomized 28 patients to either immediate loading in an orthosis or traditional serial plaster casting and showed improved clinical functional outcomes in the immediate loading group.

Kangas and coauthors’42 level I study randomized 50 patients treated surgically for an acute Achilles tendon rupture to receive either early movement or immobilization. The calf muscle strength results were somewhat better in the early motion group, whereas other outcome results obtained in the two cohorts were similar.

Finally, Maffulli and coworkers’37 Level I study showed that patients who were randomized to an early weight-bearing protocol had shortened the time of recovery without increased complications.

In contrast with the studies detailed earlier, Kauranen and researchers’35 and Petersen and investigators’39 Level I study showed no improvement in outcome for patients treated with and with an active brace and CAM walker versus a plaster cast after surgical repair of acute Achilles tendon ruptures.

A Level I meta-analysis by Suchak and colleagues40 included six prospective RCTs33,34, 37, 38, 42, 43 that were pooled to include 315 patients treated with surgical repair and postoperative immobilization (n = 156) or early functional rehabilitation (n = 159). The pooled results showed no difference in the rerupture rate in the immobilized and functional rehabilitation cohorts (3.8% vs. 2.5%, respectively) and no difference in the infection rates (3.8% vs. 3.1%, respectively). However, the functional rehabilitation cohort had improved subjective responses (88% vs. 62%) and less complications (e.g., scar adhesions and transient sural nerve deficits) (5.8% vs. 13.5%). The authors conclude that early functional rehabilitation for postoperative care of Achilles tendon ruptures treated with surgery improves patient satisfaction with reduced minor and major complications.

Finally, it is strongly recommended with support from the existing literature (Levels of Evidence I and II, grade A recommendation) that that early functional rehabilitation for postoperative care of Achilles tendon ruptures treated with surgery improves patient function and satisfaction, and in some cases, reduces minor and major complications. Table 69-2 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of Achilles tendon rupture.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Kastelic J, Baer E. Deformation in tendon collagen. Symp Soc Exp Biol. 1980;34:397-435.

2 Puddu G, Ippolito E, Postacchini F. A classification of Achilles tendon disease. Am J Sports Med. 1976;4:145-150.

3 Kannus P, Jozsa LG. Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:1507-1525.

4 Jozsa LG, Kannus P. Tendon pathology: Injuries, diseases and other disorders. In: Jozsa LG, Kannus P, editors. Human Tendons: Anatomy, Physiology, and Pathology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1997:161-254.

5 Arner O, Lindholm A, Orell SR. Histologic changes in subcutaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon; a study of 74 cases. Acta Chir Scand. 1959;116:484-490.

6 Jozsa L, Balint BJ, Reffy A, Demel Z. Fine structural alterations of collagen fibers in degenerative tendinopathy. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1984;103:47-51.

7 Jozsa L, Reffy A, Balint JB. Polarization and electron microscopic studies on the collagen of intact and ruptured human tendons. Acta Histochem. 1984;74-2:209-215.

8 Maffulli N, Barrass V, Ewen SW. Light microscopic histology of Achilles tendon ruptures. A comparison with unruptured tendons. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:857-863.

9 Cetti R, Junge J, Vyberg M. Spontaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon is preceded by widespread and bilateral tendon damage and ipsilateral inflammation: A clinical and histopathologic study of 60 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:78-84.

10 Astrom M, Rausing A. Chronic Achilles tendinopathy. A survey of surgical and histopathologic findings. Clin Orthop. 1995;316:151-164.

11 Movin T, Gad A, Reinholt FP, Rolf C. Tendon pathology in long-standing achillodynia. Biopsy findings in 40 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:170-175.

12 Carden DG, Noble J, Chalmers J, et al. Rupture of the calcaneal tendon. The early and late management. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69:416-420.

13 Leppilahti J, Puranen J, Orava S. Incidence of Achilles tendon rupture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:277-279.

14 Stein SR, Luekens CAJr. Closed treatment of Achilles tendon ruptures. Orthop Clin North Am. 1976;7:241-246.

15 Suchak AA, Bostick G, Reid D, et al. The incidence of Achilles tendon ruptures in Edmonton, Canada. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:932-936.

16 Cetti R, Christensen SE, Ejsted R, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. A prospective randomized study and review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:791-799.

17 Postacchini F, Puddu G. Subcutaneous rupture of the Achilles tendon. Int Surg. 1976;61:14-18.

21 Moller M, Movin T, Granhed H, et al. Acute rupture of tendon Achillis. A prospective randomised study of comparison between surgical and non-surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:843-848.

22 Nistor L. Surgical and non-surgical treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. A prospective randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:394-399.

23 Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Siddiqui F, et al. Treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: A systematic overview and meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 400; 2002; 190-200.

24 Khan RJ, Fick D, Keogh A, et al. Treatment of acute achilles tendon ruptures. A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2202-2210.

25 Wong J, Barrass V, Maffulli N. Quantitative review of operative and nonoperative management of Achilles tendon ruptures. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:565-575.

26 Schroeder D, Lehmann M, Steinbreuch K. Treatment of acute Achilles tendon ruptures: Open versus percutaneous repair vs. conservative treatment. A prospective randomized study. Orthopedic Transcripts. 1997;21:1228.

27 Coombs R. Prospective trial of conservative and surgical treatment of Achilles tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1981;63B:288.

28 Majewski M, Rickert M, Steinbruck K. [Achilles tendon rupture. A prospective study assessing various treatment possibilities]. Orthopade. 2000;29:670-676.

29 Thermann H, Zwipp H, Tscherne H. [Functional treatment concept of acute rupture of the Achilles tendon. 2 years results of a prospective randomized study]. Unfallchirurg. 1995;98:21-32.

30 Cretnik A, Zlajpah L, Smrkolj V, Kosanovic M. The strength of percutaneous methods of repair of the Achilles tendon: A biomechanical study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:16-20.

31 Goren D, Ayalon M, Nyska M. Isokinetic strength and endurance after percutaneous and open surgical repair of Achilles tendon ruptures. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26:286-290.

32 Lim J, Dalal R, Waseem M. Percutaneous vs. open repair of the ruptured Achilles tendon—a prospective randomized controlled study. Foot Ankle Int. 2001;22:559-568.

33 Cetti R, Henriksen LO, Jacobsen KS. A new treatment of ruptured Achilles tendons. A prospective randomized study. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 308; 1994; 155-165.

34 Costa ML, Shepstone L, Darrah C, et al. Immediate full-weight-bearing mobilisation for repaired Achilles tendon ruptures: A pilot study. Injury. 2003;34:874-876.

35 Kauranen K, Kangas J, Leppilahti J. Recovering motor performance of the foot after Achilles rupture repair: A randomized clinical study about early functional treatment vs. early immobilization of Achilles tendon in tension. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:600-605.

36 Kerkhoffs GM, Struijs PA, Raaymakers EL, Marti RK. Functional treatment after surgical repair of acute Achilles tendon rupture: Wrap vs walking cast. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:102-105.

37 Maffulli N, Tallon C, Wong J, et al. Early weightbearing and ankle mobilization after open repair of acute midsubstance tears of the achilles tendon. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:692-700.

38 Mortensen HM, Skov O, Jensen PE. Early motion of the ankle after operative treatment of a rupture of the Achilles tendon. A prospective, randomized clinical and radiographic study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:983-990.

39 Petersen OF, Nielsen MB, Jensen KH, Solgaard S. [Randomized comparison of CAM walker and light-weight plaster cast in the treatment of first-time Achilles tendon rupture]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2002;164:3852-3855.

40 Suchak AA, Spooner C, Reid DC, Jomha NM. Postoperative rehabilitation protocols for Achilles tendon ruptures: A meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 445; 2006; 216-221.

41 Saleh M, Marshall P, Senior R, et al. The Shefield splint for controlled early mobilization after rupture of the calcaneal tendon. A prospective randomised comparison with plaster treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74-B:206-209.

42 Kangas J, Pajala A, Siira P, et al. Early functional treatment versus early immobilization in tension of the musculotendinous unit after Achilles rupture repair: A prospective, randomized, clinical study. J Trauma. 2003;54:1171-1181.

43 Maffulli N, Tallon C, Wong J, et al. No adverse effect of early weight bearing following open repair of acute tears of the Achilles tendon. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2003;43:367-379.