Chapter 15 What Is the Best Management of Digital Triggering?

Stenosing tenosynovitis, or trigger finger, was first described by Notta in 1850.1 It is one of the most common hand conditions in adults treated by primary care providers, orthopedic and plastic surgeons, and hand surgeons, affecting a reported 2.6% of the general population.2 The affected digit “triggers” or locks during active flexion, which is often associated with pain. In severe cases, the digit can become fixed in flexion or extension, leading to joint contracture. Despite its common occurrence, no clear consensus exists regarding the management of trigger fingers. Nonsurgical treatment has generally been advocated as the initial therapy, with either splinting of the affected digit or steroid injection into the flexor tendon sheath. Surgery traditionally has been reserved for those who do not respond to conservative therapy, with open division of the A1 pulley as the definitive treatment. In recent years, percutaneous release of the A1 pulley has gained popularity as an alternative surgical technique. Splinting and steroid injection are easily performed in the office, are relatively safe and inexpensive, and require no post-treatment activity restrictions for the patient. However, prolonged splinting regimens may be required, and persistent symptoms and recurrence are more likely to occur, especially if symptoms are long-standing.3,4 Surgery usually provides permanent relief but is often more costly, involving potential time away from work and a risk for surgical complications. Systemic diseases such as amyloidosis, mucopolysaccharidoses, diabetes mellitus, and rheumatoid arthritis have been associated with digital triggering.5 The most common of these is diabetes mellitus, in which the incidence rate of trigger finger is 4% to 10%.6 Studies have suggested that conservative therapy is less effective in these patients, but complications such as infection and delayed wound healing may be special surgical concerns.

OPTIONS

Symptomatic patients may first present to primary care providers, who must decide which patients are unlikely to respond to conservative therapy and refer them to a surgeon. For the remaining patients, options include activity modifications, oral anti-inflammatory agents, splinting, and steroid injection.5 For splinting regimens, the choice of joint for immobilization in the affected digit and length of treatment need to be determined. For injection therapy, decisions include which steroid preparation to use, what volume and location to inject, how many injections to give, and at what time intervals repeat injections should be given. Although division of the A1 pulley is the widely accepted surgical procedure, the surgeon has a choice between open versus percutaneous technique. Ideally, systematic review of the published evidence should allow development of a treatment algorithm that can be followed reliably to achieve the safest, most effective results with the greatest level of patient satisfaction, whereas keeping costs at a minimum. In an effort toward reaching this goal, discussion in this chapter is limited to those comparative studies that provide the highest levels of evidence (Levels I-III) identified after systematic review of the published literature. Higher quality clinical studies are more likely to provide convincing evidence for influencing medical treatment decisions.

EVIDENCE

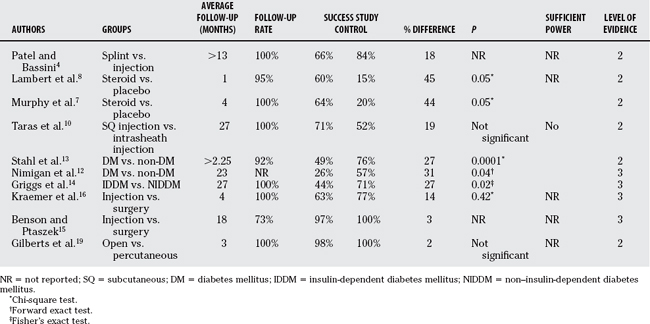

Few controlled studies comparing splinting with steroid injection have been published. In their prospective study, Patel and Bassini4 compared 50 consecutive patients who were treated with metacarpophalangeal (MP) joint splinting with 50 patients who were treated with intrasheath injection of betamethasone (Level of Evidence II). Severity of triggering was graded, and patients with minimal pain, “uneven” movements that did not interfere with hand function, or who were symptom free at the end of the 1-year study period were considered successfully treated. One fourth of the injection group required a single repeat injection 2 weeks after the initial injection. Success was achieved in 66% of the splinted group and 84% of the injected group. Symptoms recurred in 12% of the splinted patients during the 1-year follow-up period; none recurred in the injection group. Patients with symptoms for longer than 6 months before treatment, multiple digital involvement, or triggering at time of presentation faired the worst. The authors comment that splinting was the least effective for trigger thumbs, and that more than 6 weeks of splinting was necessary to achieve success in one third of the patients.4

Although splinting is painless and noninvasive, it interferes with normal hand use, prolonged treatment may be necessary, and success relies directly on patient compliance. If a single steroid injection can provide comparable or better success rates, then it might be preferred over splinting, despite the discomfort associated with injection. Controlled prospective trials have compared a single injection of steroid into the flexor tendon sheath with placebo injection of local anesthetic.7,8 In separate studies by Murphy and colleagues7 and Lambert and coworkers8 (Level II), a single intrasheath injection of betamethasone or methylprednisolone, respectively, cured 64% and 60% of the patients. Both studies were properly blinded, with the intervention and evaluations for each patient performed by different clinicians. Although the results were statistically significant, it is interesting to note that placebo injection was effective in 20% and 16% of patients in the two studies. No recurrences were reported within the relatively short (one8 and four7 months) follow-up periods.

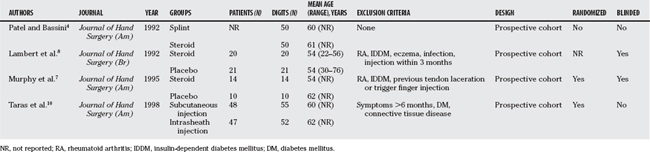

Initial published results in the 1950s for corticosteroid injection in the treatment of trigger fingers demonstrated short-term efficacy,9,10 with more lasting results achieved after the development of longer acting corticosteroid preparations.10,11 Choice of steroid is usually based on physician preference, and no good comparison studies of steroid preparations have been done. Betamethasone, methylprednisolone, and triamcinolone are common choices. Injection volume and concentration of steroid have also varied widely among studies, with essentially all studies advocating injection into the flexor tendon sheath just distal to the A1 pulley. An interesting controlled prospective study by Taras and researchers10 (Level II) explored this recommendation by comparing intrasheath with subcutaneous injection. The steroid was mixed with radio-opaque contrast dye. After their assigned injections, the actual location of each injection was verified radiographically. Symptom resolution was achieved in 71% of the subcutaneous group and 52% of the intrasheath group after 27-month average follow-up. Overall, 62% of the patients were treated successfully. Only 30% of the attempted injections into the tendon sheath were completely accurate. Recalculation of the results based on true location of steroid delivery had the following outcome: intrasheath, mixed, or subcutaneous showed no change in success rates. Although the results suggest that subcutaneous injection was as effective as intrasheath injection, the study lacked adequate power (β = 0.92). The study designs for these studies on efficacy of steroid injection are summarized in Table 15-1.

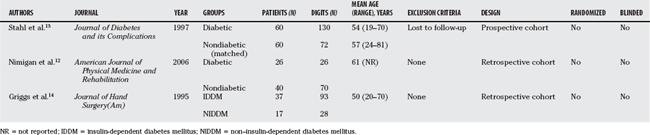

Although the physiologic explanation for greater incidence of trigger finger in patients with diabetes mellitus is unclear, it is usually reported as 4% to 10%, with some reports as high as 23%.12 Steroid injections have been believed to be less effective in the treatment of diabetic trigger fingers. Stahl and investigators13 prospectively compared the efficacy of steroid injections for trigger finger in 60 patients with diabetes with 60 nondiabetic control patients, matched for age, sex, digit involvement, occupation, and available follow-up (Level II). A maximum of three injections at 3-week intervals were allowed, with 12% of the patients with diabetes requiring three injections, whereas only 3% of the patients without diabetes did. Overall, 59% were treated successfully with steroid injection, but the response rate was significantly lower in patients with diabetes (49%) than in those without (76%). Insulin dependence and duration of symptoms before treatment did not affect the results. Long-term follow-up beyond 9 weeks was not provided. Likewise, retrospective review of 66 patients treated for trigger finger by Nimigan and coauthors12 (Level III) showed 52% response rate to up to three steroid injections, with significantly lower response in patients with diabetes (26%) than in those without diabetes (57%).12 Again, duration of symptoms and insulin dependence did not affect the results. Nearly all of the patients who underwent surgery either after did not respond to injection therapy or because of personal preference were successfully treated (97%), although 36% experienced complications. Patients with diabetes did not have greater complication rates, and stiffness was the most common postoperative problem. In contrast, Griggs and colleagues14 (Level III) found patients with insulin-dependent diabetes less likely to respond to steroid injection (44%) compared with patients with non–insulin-dependent diabetes (71%) in their retrospective review. Steroid injection was successful in only 50% of 121 digits in the 54 patients in their study. The study designs for these studies on steroid injection in patients with diabetes are summarized in Table 15-2.

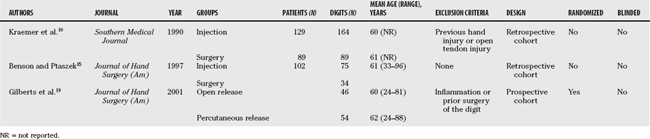

Reported efficacy for surgical release of the A1 pulley in the treatment of trigger finger has been generally excellent. However, complications resulting from steroid injection are rarely reported, whereas surgical complication rates in large controlled studies have ranged from 0%15 to as high as 36%.12 Kraemer and coworkers’16 and Benson and Ptaszek’s15 retrospective reviews (Level III) showed comparable success rates for steroid injection and surgery, but power analysis was not mentioned. Treatment outcomes were 63% success after injection and 77% success after surgery in Kraemer and coworkers’16 study.16 In Benson and Ptaszek’s15 study, injection achieved 97% success, and all surgery patients responded well.15 Sixty percent to 67% of the conservatively managed patients required only a single injection.15,16 Seven percent of one surgery group experienced complications, which were usually persistent stiffness.16 In the other study, none of the surgery patients had complications.15 Despite excellent results from open surgical release, both authors discussed the “costs” to the patient associated with surgery, including operative charges, time spent for the procedure, subsequent time off work, and the potential additional cost with a complication. However, a calculation of costs must also take into account patient preferences. Interestingly, in Benson and Ptaszek’s15 study, 73% of the patients completed a follow-up satisfaction questionnaire, in which the majority of patients recalled the pain during injection to be equal to or more severe than pain with surgery, and planned to choose surgery sooner for future trigger digits.15 None of the surveyed patients experienced surgical complications; their preferences might have differed if they had. Despite better results with surgery, both authors recommend that steroid injection remain the firstline treatment, with surgery reserved for nonresponders.15,16

Percutaneous release of the A1 pulley using a fine tenotome was first described in 1958 by Lorthioir.17 In consideration of potential additional time and costs associated with open release for trigger fingers, Eastwood and colleagues18 introduced percutaneous release using a large-gauge hypodermic needle as on office procedure. The complications most frequently reported after open release have been stiffness, scar sensitivity or pain, and wound infection or delayed healing. Presumably, needle percutaneous release would avoid painful scar and wound healing problems. However, cadaveric studies have raised the question of increased risks for incomplete pulley release, digital nerve injury, and flexor tendon injury. In 2001, Gilberts and researchers19 (Level II) prospectively compared open and percutaneous needle release in the treatment of 100 trigger digits. Although the authors report random assignment to treatment groups, their methodology describes only the use of “sealed envelopes.” Nearly all of the patients in both groups experienced symptom relief. A power analysis was not reported. No recurrences, nerve deficits, or tendon problems occurred in the 4-month follow-up period. Because both techniques were performed in an outpatient surgery facility, direct comparison of operating times was possible as an indirect measure of cost. Operating time, duration of postoperative pain, return to work, and time to regain full motion were significantly shorter in the percutaneous release group. One of the patients treated with open release required repeat surgery for “scar formation,” and one patient in each group experienced development of a minor hematoma. Table 15-3 summarizes the study designs of the reviewed studies for open and percutaneous surgical treatment of trigger finger. Finally, Table 15-4 lists the results and levels of evidence for all of the comparative studies reviewed in this chapter.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of trigger finger is believed to be straightforward by most clinicians. However, a spectrum of clinical presentations is recognized. In two of the reviewed articles, the authors use grading systems to describe the various symptoms in their patients, ranging from uneven motion only, painless triggering, to painful locked digits with palpable tendon nodules.4,7 Whether these variations represent different levels of severity, different pathophysiology, or simply alternative presentations of a common disease process remains unclear. No standardized grading system is currently in use, making direct comparison of patient groups difficult. In their cost analysis of conservative and surgical treatments, Benson and Ptaszek15 explore pain as a potential factor in their patients’ personal preferences. If pain is, indeed, an influential factor, then studies that do not take it into account may not have homogeneous patient groups for risk-benefit analysis. These limitations of the diagnostic criteria also affect the measurement of treatment success. Fleisch and coauthors20 address this in their systematic literature review of steroid injections for the treatment of trigger finger. They propose the use of a classification system for diagnosis, visual analog pain scale, and measured active digital motion to improve the assessment of treatment efficacy.

Treatment Protocols

No uniformity of treatment protocols exists, especially in the conservative management of stenosing tenosynovitis. Some authors advocate splinting of the MP joint alone,4 but each of the interphalangeal joints have also been splinted in clinical practice, presumably with reasonable results. Similarly, the reviewed studies on steroid injection used various concentrations of a wide variety of long-acting agents (triamcinolone,15 methylprednisolone,8,13 betamethasone4,7, 10, 12, 14, 15). Some studies did not report the concentration or amount of drug injected, and the majority did not report the volume of injection administered, all of which may affect the result. No consensus exists regarding the duration of treatment for splinting or steroid injection, or the maximum number or intervals for injections, which makes the determination of treatment success or failure nearly impossible. Follow-up periods in the reviewed studies varied from 1 month8 to 27 months.14 Studies with shorter follow-up periods may have falsely increased success rates and vice versa, because the natural history of trigger finger after various treatment methods remains undefined.

Costs

In the two studies that directly compared steroid injection with surgery (open technique), the authors recommend that steroid injection remain the first line of treatment, despite achieving high rates of success in their surgical groups.15,16 They based this recommendation on the “cost” associated with surgery. Cost is always difficult to estimate and generalize for analyses because charges may differ from actual costs, and time spent, as well as time lost (e.g., from work), need to be considered. In addition, the potential additional costs associated with a possible complication are often taken into account in the analysis. The costs of an intervention can vary based on the setting in which it is performed. Thus, the cost of a percutaneous A1 pulley release might change drastically if the procedure is performed in a hospital outpatient facility instead of a surgeon’s office. For this reason, recommendations based on “cost” need to be considered in the context of the particular setting and may not translate outside of that setting.

Although activity modification and oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are used for the treatment of trigger finger, this discussion remains limited to the more widely utilized treatments of splinting, steroid injection, and surgery. Published case series abound for each of these modalities, but only controlled studies were chosen for this chapter to try to present the strongest evidence available. Unfortunately, the resulting body of literature is quite small. The only controlled study on splinting prospectively compared it with steroid injection but failed to report any statistical analysis.4 The method of assignment to the steroid injection group was not delineated, and clinical evaluations were not blinded. Thus, the body of evidence is insufficient to allow any recommendation for or against splinting as an effective treatment for trigger finger.

For steroid injection, the literature is stronger, with two prospective, triple-blinded, placebocontrolled studies available.7,8 However, the randomization process was not reported in one8 and was based on odd/even date for the other,7 both of which may be sources of potential selection bias. The studies had relatively small groups, but steroid injection was significantly more effective than lidocaine placebo in both. Of note, both studies excluded patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The study comparing subcutaneous with intrasheath steroid injection was novel, but unfortunately had insufficient power to support the alternative recommendation that subcutaneous injection is sufficient for treating trigger finger.10 The authors report their β value as 0.08; recalculation shows the study power is actually 0.08 (8% power), with a β value of 0.92. Patients with diabetes mellitus had significantly poorer response to steroid injection than patients without diabetes, although follow-up evaluation was not blinded in any of the reviewed studies.12,13 Longer duration of symptoms did not adversely affect response to steroid injection. Although neither study showed any difference between patients with insulin-dependent and non–insulin-dependent diabetes, a single small, retrospective study comparing these two populations showed that patients with insulindependent diabetes fared worse.14 The evidence is fair in support of steroid injection in the treatment of trigger finger, with fair evidence that it is less effective in patients with diabetes mellitus, who may be more likely to require surgical management. No contraindication to its use in insulin-dependent patients has been found, but evidence regarding its efficacy is conflicted.

The two retrospective studies comparing steroid injection with open A1 pulley release showed no significant difference between the two treatments,15,16 but power analyses were not performed to rule out the possibility of type II error. Lack of randomization and blinding make selection and ascertainment bias potential confounders as well. No complications were associated with steroid injection, but 7% of the open surgical release patients experienced minor complications.16 A single prospective, randomized, controlled study comparing percutaneous needle release with open A1 pulley release showed equal efficacy with no major complications in either group.19 However, the randomization process was not clearly defined and assessment was not blinded. Fair evidence exists to support the effectiveness of surgery in the treatment of trigger finger, but insufficient evidence to recommend it over steroid injection. The body of evidence is too small to make any recommendations regarding percutaneous versus open surgical techniques.

Based on currently published evidence, the following treatment algorithm is proposed by this author (Level V): splinting may be tried first for the treatment of stenosing tenosynovitis of the finger. Its effectiveness is dependent on the level of patient compliance. It is less likely to be effective for trigger thumb. Successful treatment is defined as pain-free resolution of symptoms with full active motion. If splinting fails, steroid injection is likely to be effective, regardless of the duration of symptoms prior to presentation. A maximum of three intrasheath injections of a long acting corticosteroid is given every 3 weeks as necessary. In patients with diabetes mellitus, only one steroid injection is recommended, followed by surgery if no response. If injection fails, open surgical release of the A1 pulley is recommended. Percutaneous needle release may be performed, based on surgeon experience, because a learning curve exists. The most common complication after surgery is stiffness. The major treatment recommendations are presented in summary form in Table 15-5, with their accompanying grades of recommendation.

TABLE 15-5 Summary of Recommendations for Treatment of Trigger Finger

| RECOMMENDATIONS | ARTICLES AND LEVELS OF EVIDENCE | GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

| Splinting is effective in the treatment of trigger finger. | 2 | B |

| A single intrasheath steroid injection is effective in the treatment of trigger finger. | 2, 2 | B |

| Subcutaneous steroid injection at the A1 pulley is as effective as intrasheath injection. | 2 | B |

| Patients with diabetes with trigger finger are less likely to respond to steroid injection and should be treated surgically. | 3, 3 | B |

| Patients with insulin-dependent diabetes with trigger finger should not be treated with steroid injection. | 3 | B |

| A series of steroid injections is as effective as and less risky than surgery for trigger finger. | 3, 3 | B |

| Percutaneous A1 pulley release is as effective as and less morbid than open pulley release. | 2 | B |

1 Notta A. Recherches sur une affection particulier des gaines tendineuses de la main. Arch Gen Med. 1850;24:142.

2 Strom L. Trigger finger in diabetes. J Med Soc N J. 1977;74:951-954.

3 Rhoades CE, Gelberman RH, Manjarris JF. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the fingers and thumb. Clin Orthop. 1984;190:236-238.

4 Patel MR, Bassini L. Trigger fingers and thumb: When to splint, inject, or operate. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1992;17:110-113.

5 Ryzewicz M, Wolf JM. Trigger digits: Principles, management, and complications. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2006;31:135-146.

6 Lapidus PW, Guidotti EP. Stenosing tenovaginitis of the wrist and fingers. Clin Orthop. 1972;83:87-90.

7 Murphy D, Failla JM, Koniuch MP. Steroid versus placebo injection for trigger finger. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1995:628-631.

8 Lambert MA, Morton RJ, Sloan JP. Controlled study of the use of local steroid injection in the treatment of trigger finger and thumb. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1992;17:69-70.

9 Howard LD, Pratt DR, Bunnell S. The use of compound F (hydrocortisone) in operative and non-operative conditions of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1953;35:994-1002.

10 Taras JS, Raphael JS, Pan WT, et al. Corticosteroid injections for trigger digits: Is intrasheath injection necessary? J Hand Surg [Am]. 1998;23:717-722.

11 Quinnell RC. Conservative management of trigger finger. Practitioner. 1980;244:187-190.

12 Nimigan AS, Ross DC, Gan BS, et al. Steroid injection in the management of trigger fingers. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:36-43.

13 Stahl S, Kanter Y, Karnielli E. Outcome of trigger finger treatment in diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 1997;11:287-290.

14 Griggs SM, Weiss APC, Lane LB, et al. Treatment of trigger finger in patients with diabetes mellitus. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1995;20:787-789.

15 Benson LS, Ptaszek AJ. Injection versus surgery in the treatment of trigger finger. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1997;22:138-144.

16 Kraemer BA, Young L, Arfken C. Stenosing flexor tenosynovitis. South Med J. 1990;83:806-811.

17 Lorthioir J. Surgical treatment of trigger finger by a subcutaneous method. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1985;40:793-795.

18 Eastwood DM, Gupta KJ, Johnson DP. Percutaneous release of the trigger finger: An office procedure. J Hand Surg [Am]. 1992;17:114-117.

19 Gilberts ECAM, Beekman WH, Stevens HJPD, et al. Prospective randomized trial of open versus percutaneous surgery for trigger digits. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2001;26:497-500.

20 Fleisch SB, Spindler KP, Lee DH. Corticosteroid injections in the treatment of trigger finger: A level I and II systematic review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:166-171.