Chapter 81 What Blood Conservation Techniques for Total Joint Arthroplasty Work?

In 1997, after the tainted blood issues of the 1980s, the Canadian Commission of Inquiry on the Blood Supply (The Krever Commission; more information is available online at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ahc-asc/activit/com/krever_e.html) recommended the promotion of the “appropriate use of, and alternatives to, blood components and blood products.” Therefore, it is not a question of whether blood conservation should be considered, but rather which of the available modalities of blood conservation is ef-fective, and moreover cost-effective, in joint arthroplasty.

It should be stressed that blood conservation is not limited to avoiding allogeneic blood utilization but also includes the appropriate utilization of blood and blood products. Simple rules to ordering and administering blood products should be established, published, and reinforced at every institution carrying out joint arthroplasty: (1) A transfusion guideline should be established (Table 81-1); (2) ordering of blood product should include the indication for its administration (e.g., transfuse 1 unit of RBCs for a hemoglobin concentration of 70 g/L), and (3) RBC units should be administered one unit at a time with the patient reassessed before a second unit is administered. Following these simple guidelines will improve the utilization of blood products and reduce unnecessary transfusions.

TABLE 81-1 Guideline for Red Blood Cell Transfusion Based on Hemoglobin Concentration

| HEMOGLOBIN CONCENTRATION (G/L) | TRANSFUSION RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

| >100 | Transfusion required only in exceptional circumstances |

| 70-100 | Transfusion required only if there are signs and symptoms of impaired oxygen delivery or if patient is at high risk* |

| <70 | Likely be appropriate |

| <60 | Transfusion highly recommended |

Level III evidence.

* Patients at high risk include those with known coronary artery or valvular hearts disease, previous cerebral vascular event, or poor oxygenation.

OPTIONS

Blood conservation includes preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative modalities. Preoperative modalities focus on the expansion of the RBC mass either ex vivo using preoperative autologous blood donation (PAD) or in vivo using iron supplementation and erythrocyte-stimulating agents (ESA) (e.g., Eprex, Ortho Biotech, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Intraoperative techniques focus on reducing the loss of RBCs or the reclamation of shed blood. Surgical technique and the strict attention to hemostasis is the single-most important factor for which there is no alternative. Other methods purported to reduce blood loss include controlled hypotension, acute normovolemic hemodilution (ANH), antifibrinolytic agents, and cell salvage. Postoperative blood conservation modalities include cell salvage, continued adherence to a transfusion guideline, and the careful management of hemostasis, keeping in mind the need for postoperative deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis (see Chapter 2).

EVIDENCE

Preoperative Autologous Donation

The efficacy of PAD in reducing patient exposure to allogeneic blood has been demonstrated in numerous randomized clinical trials in several operative settings.1 This evidence is supported by controlled observational trials, but the overall level of evidence remains poor because there are no blinded trials.1

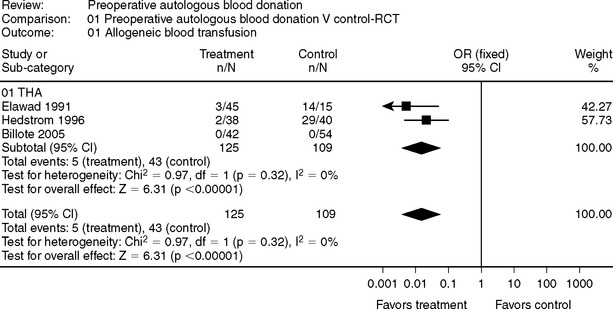

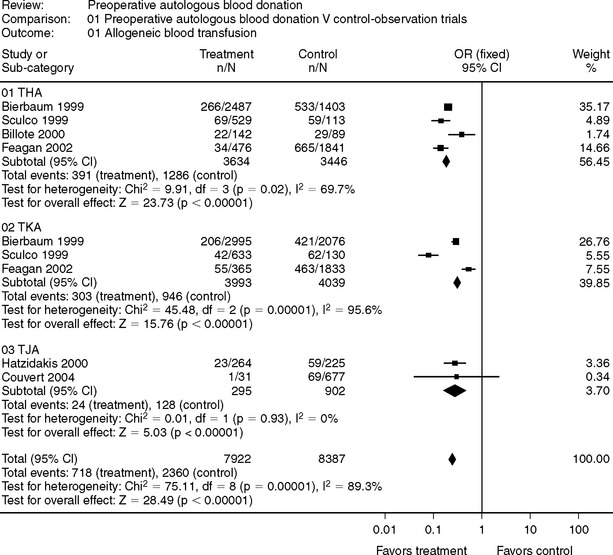

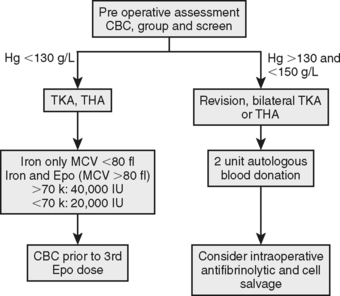

In joint arthroplasty, the evidence in support of PAD is less convincing (Fig. 81-12–4 and 81-25–11). Some authors have concluded that there is no role for PAD in joint arthroplasty, and if the entire surgical population were considered candidates for PAD, then the evidence would support this contention.1 However, for patients who are at increased risk for a blood transfusion (e.g., revision surgery, small body habitus [<70 kg]) and are not anemic (i.e., patient capable of regenerating RBC mass after donation), PAD may be a viable blood conservation modality. It should be the role of a perioperative blood conservation program to identify appropriate patients for PAD using an up-to-date database to evaluate its use.

Preoperative Iron and Erythropoietin Therapy

The incidence of preoperative anemia in patients scheduled for the total arthroplasty is between 20% and 35%.12,13 The causative factor of this anemia is multifactorial, but the two most common causes are iron deficiency anemia and anemia of chronic disease. Importantly, preoperative anemia is the single-most treatable risk factor for a blood transfusion associated with joint arthroplasty surgery.12 Iron supplementation and the use of erythropoietin (Epo) are the primary modes of therapy of preoperative anemia.

The incidence of preoperative iron deficiency anemia is unknown, but elderly patients have a number of risk factors for iron deficiency including use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and poor diet. Iron deficiency anemia is a hypochromic, microcytic anemia, and the RBC mean cell volume (MCV) is a good predictor for response to iron supplementation.14 For anemia (hemoglobin concentration <120 g/L) and MCV less than 80 fL, a 4-week course of supplemental iron results in an 11- to 12-g/L increase in hemoglobin concentration.14 In contrast, anemia with an MCV greater than 90 fL does not respond to iron supplementation alone.14

The routine use of perioperative supplemental iron therapy is controversial in that it has little effect on blood transfusion.15,16 However, in patients in whom erythropoiesis is either stimulated by PAD or recombinant Epo, iron supplementation is recommended. The source of iron is arguably unimportant as long as the goal is to add approximately 100 mg elemental iron to the daily diet. In fact, dietary heme-iron in red meat, poultry, and fish is more readily absorbed than formulated dietary supplements. Other sources of iron include plant food such as lentils and beans. If, however, oral iron absorption is poor and iron supplementation is still required, intravenous iron sucrose is a safe and effective alternative.17,18 Iron sucrose is no more effective than oral iron preparations in increasing the RBC mass.19,20

Epo is a naturally-occurring hormone secreted by the kidneys in response to low partial pressure of oxygen. Epo stimulates effective erythropoiesis only if there are adequate iron stores, and the use of Epo should be combined with supplemental iron. The efficacy of preoperative Epo in total joint arthroplasty (TJA) has been demonstrated in double-blind, randomized, controlled trials, increasing preoperative hemoglobin concentration by 15 g/L whereas reducing the frequency of RBC transfusion by 50%.21 In a systematic review of the literature, Laupacis and colleagues22 found that the overall odds ratio of RBC transfusion in patients who received Epo was 0.36 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.24–0.56).22

In addition, several studies have evaluated the use of Epo in the clinical setting and confirmed it effectiveness in reducing the exposure of patient to allogeneic blood transfusions.13,23, 24 In a clinical observation trial, Karkouti and colleagues13 demonstrated a reduction in transfusion rates for patients with anemia undergoing TJA from 56.1% to 16.4% when treated before surgery with Epo, and the adjusted odds ratio of RBC transfusion in the Epo group was 0.33 (95% CI, 0.21–0.49).13

Although Epo is undeniably an effective therapy in reducing the risk for an allogeneic blood transfusion, particularly for the patient with anemia, there are two caveats to its routine use that should be considered. First, it remains an expensive therapy ($500 [Canadian currency] per injection), and second, concerns about the safety of Epo have been identified. The first safety concern is that the use of an ESA can increased the risk for thromboembolic events. In a large (N = 681), randomized, control trial, patients with anemia who received Eprex before spinal surgery had a significantly greater rate of thromboembolic events compared with patients given placebo (8.2% vs. 4.1%; more information is available online at: http://download.veritasmedicine.com/PDF/CR004621_CSR.pdf). The second and perhaps more worrisome safety concern is the increased risk for serious adverse events and death when they are used to treat anemia in patients with cancer.25 These concerns led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to enhance its safety warnings for Epo and other ESAs (more information is available online at: http://www.fda.gov/cder/drug/infopage/RHE/default.htm). Patients should be informed of these newly recognized safety concerns, and the cautious use of ESA should be recommended. It will likely be some time before the importance of these safety concerns for patients with TJA can be clarified.

Intraoperative Acute Normovolemic Hemodilution

Several meta-analyses have considered the efficacy of ANH, including trials from various surgical procedures.1,26, 27 Conclusions from these reviews are as follows: (1) The effectiveness of ANH is dependent of the number of units sequestered and the degree of hemodilution tolerated; (2) the trials included in the review were not blinded, resulting in an overestimated effect size; and (3) when the outcome decision (i.e., allogeneic blood transfusion) was considered under a transfusion protocol, the effect size was reduced.

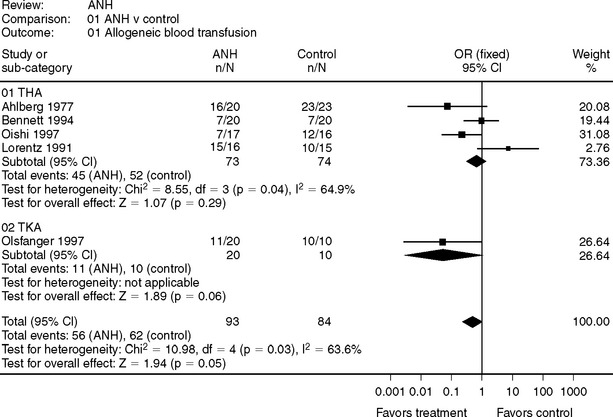

Randomized, controlled trials conducted in the joint arthroplasty are presented in Figure 81-3.28–32 Oishi and colleagues30 utilized ANH and intraoperative cell salvage, and compared the rate of any transfusion, allogeneic or autologous. ANH is of minimal benefit in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) when a tourniquet is used because most blood loss occurs after the tourniquet is deflated at a time when the sequestered blood is retransfused. For total hip arthroplasty (THA), a prolonged severe anemia would be required to accomplish sufficient hemodilution to reduce the risk for an allogeneic blood transfusion, and this has perioperative risk in and of itself. Therefore, the evidence does not support the routine use of ANH because it offers only limited benefit in terms of blood conservation and has an unproven safety profile.

Intraoperative Antifibrinolytics

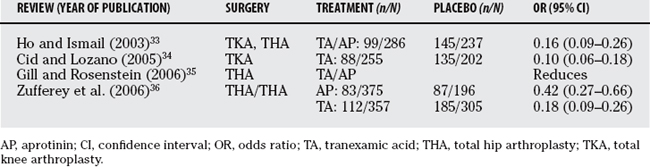

Surgical stress, limb trauma, and the application of a tourniquet can activate fibrinolysis and increase blood loss. Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have focused on the use of antifibrinolytics in joint arthroplasty (Table 81-2).33–36 While these reviews conclude that antifibrinolytics reduce blood loss and allogeneic blood transfusion, there are caveats that should not be overlooked before tranexamic acid or aprotinin are used in clinical practice. The first consideration relates to the law of diminishing returns. Zufferey and coworkers36 point to a direct relation between transfusion rate and effect size such that the number needed to treat to avoid an allogeneic blood transfusion decreases as baseline transfusion rate increases.36 Therefore, the benefit of antifibrinolytics will be reduced as transfusion rates are reduced, and many of the studies had greater transfusion rates than are found currently.

TABLE 81-2 Meta-analytic Results for the Allogeneic Transfusion Rates for Patient Undergoing Joint Arthroplasty Surgery Comparing the Effects of Antifibrinolytic with Placebo

The second caveat has to do with the different dosing regimens used in the trials included in these systematic reviews. Although the high-dose aprotinin and tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) treatments would seem to be effective, the optimal dose has not been established. In addition, several observational studies and a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials have shown that aprotinin is associated with increased risk for renal dysfunction.37–39 These findings led the FDA to restrict the indications for aprotinin to high-risk coronary artery bypass surgery (more information is available at: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2006/NEW01529.html). Tranexamic acid has been shown to significantly reduce allogeneic blood exposure in joint arthroplasty, but its benefit may be limited to settings associated with high blood loss.33–36 Importantly, the adverse-effect profile or risks for these drugs has not been established, making it difficult to establish a risk/benefit estimate.

INTRAOPERATIVE AND POSTOPERATIVE CELL SALVAGE

Cell salvage can be accomplished producing either a washed or filtered RBC product and can continue into the postoperative period for up to 6 hours by reclaiming shed blood from surgical drains. The inflammatory response to retransfusion of filtered blood has been found to be greater than the response to a washed RBC product, but the consequence of this difference has not been identified.40–42

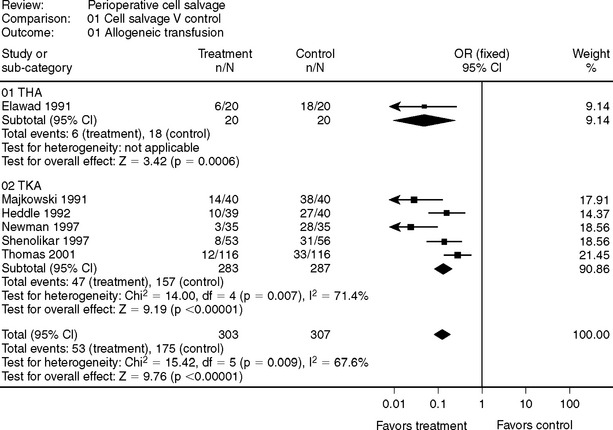

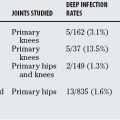

Although not supported by clinical evidence, drains are used in joint arthroplasty surgery to reduce hematoma formation and the incidence of wound infection. Some evidence would suggest that these benefits are not realized, and that drain placement may increase postoperative blood loss.43,44 If a drain is placed, there is evidence from randomized, controlled trails, particularly in TKA, that cell salvage can effectively reduce the need for an allogeneic blood transfusion (Fig. 81-4).2,45–49

Intraoperative cell salvage can be utilized in THA; however, there are no randomized, control trials to support its general use. In revision THA, the use of cell salvage is reported in retrospective cohort studies to reduce both net perioperative blood loss50 and number of allogeneic blood transfusions.51 This Level III evidence is not sufficient to recommend the routine use of cell salvage in THA.

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Levels of Evidence

PAD, ANH, and cell salvage have never been compared using blinded, randomized, controlled trials, and we must rely on open-labeled trails, which can overestimate the effect size. Some studies are in the planning stage to overcome this shortfall, but in the meantime, the use of these modalities should be limited to patients at high risk for a blood transfusion with surgery.

Comparison of Blood Conservation Modalities

Numerous trials compare the efficacy of one blood conservation modality with another (e.g., PAD compared with ANH52 or PAD with perioperative cell salvage).53,54 These comparisons would be valuable if the efficacy of at least one modality was well established, but as described earlier, this is not the case. Trials comparing different as yet unproven modalities were not considered in this chapter unless a placebo group was included.

Cost Benefit

Until evidence supports more aggressive perioperative blood conservation management, we recommend the restricted management outline in Figure 81-5 and Table 81-3. Iron and Epo therapy for moderate preoperative anemia and PAD for patients at high risk for an allogeneic blood transfusion with hemoglobin concentration in the reference range are recommended. Evidence from observational11,13 and randomized21,22 trials support a program approach to perioperative blood conservation, but each program should be tailored to its institution using site-specific data to guide the utilization of specific interventions.

1 Carless P, Moxey A, O’Connell D, et al. Autologous transfusion techniques: A systematic review of their efficacy. Transfus Med. 2004;14:123-144.

2 Elawad AA, Ohlin AK, Berntorp E, et al. Intraoperative autotransfusion in primary hip arthroplasty. A randomized comparison with homologous blood. Acta Orthop Scand. 1991;62:557-562.

3 Hedstrom M, Flordal PA, Ahl T, et al. Autologous blood transfusion in hip replacement. No effect on blood loss but less increase of plasminogen activator inhibitor in a randomized series of 80 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:317-320.

4 Billote DB, Glisson SN, Green D, et al. A prospective, randomized study of preoperative autologous donation for hip replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1299-1304.

5 Bierbaum BE, Callaghan JJ, Galante JO, et al. An analysis of blood management in patients having a total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:2-10.

6 Sculco TP, Gallina J. Blood management experience: Relationship between autologous blood donation and transfusion in orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 1999;22(suppl):S129-S134.

7 Billote DB, Glisson SN, Green D, et al. Efficacy of preoperative autologous blood donation: Analysis of blood loss and transfusion practice in total hip replacement. J Clin Anesth. 2000;12:537-542.

8 Feagan BG, Wong CJ, Johnston WC, et al. Transfusion practices for elective orthopedic surgery. CMAJ. 2002;166:310-314.

9 Woolson ST, Pottorff G. Use of preoperatively deposited autologous blood for total knee replacement. Orthopedics. 1993;16:137-141.

10 Hatzidakis AM, Mendlick RM, Mckillip T, et al. Preoperative autologous donation for total joint arthroplasty: An analysis of risk factors for allogenic transfusion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:89-100.

11 Couvret C, Laffon M, Baud A, et al. A restrictive use of both autologous donation and recombinant human erythropoietin is an efficient policy for primary total hip or knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:262-271.

12 Shander A, Knight K, Thurer R, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of anemia in surgery: A systematic review of the literature. Am J Med. 2004;116(suppl 7A):58S-69S.

13 Karkouti K, Mccluskey SA, Evans L, et al. Erythropoietin is an effective clinical modality for reducing RBC transfusion in joint surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:362-368.

14 Andrews CM, Lane DW, Bradley JG. Iron pre-load for major joint replacement. Transfus Med. 1997;7:281-286.

15 Kasper SM, Ellering J, Stachwitz P, et al. All adverse events in autologous blood donors with cardiac disease are not necessarily caused by blood donation. Transfusion. 1998;38:669-673.

16 Sutton PM, Cresswell T, Livesey JP, et al. Treatment of anaemia after joint replacement. a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial of ferrous sulphate versus placebo. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:31-33.

17 Faich G, Strobos J. Sodium ferric gluconate complex in sucrose: Safer intravenous iron therapy than iron dextrans. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;33:464-470.

18 Reed J, Charytan C, Yee J. The safety of intravenous iron sucrose use in the elderly patient. Consult Pharm. 2007;22:230-238.

19 Miller HJ, Hu J, Valentine JK, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of intravenous ferric gluconate in the treatment of iron deficiency anemia in patients without kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1327-1328.

20 Weisbach V, Skoda P, Rippel R, et al. Oral or intravenous iron as an adjuvant to autologous blood donation in elective surgery: A randomized controlled study. Transfusion. 1999;39:465-472.

21 Feagan BG, Wong CJ, Kirkley A, et al. Erythropoietin with iron supplementation to prevent allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip joint arthroplasty. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:845-854.

22 Laupacis A, Feagan B, Wong C. Effectiveness of perioperative recombinant human erythropoietin in elective hip replacement. COPES Study Group. Lancet. 1993;342:378.

23 Rosencher N, Poisson D, Albi A, et al. Two injections of erythropoietin correct moderate anemia in most patients awaiting orthopedic surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:160-165.

24 Wong CJ, Vandervoort MK, Vandervoort SL, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial of a blood conservation algorithm in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. Transfusion. 2007;47:832-841.

25 Burton A. Is it all over for erythropoietin? Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:285.

26 Bryson GL, Laupacis A, Wells GA. Does acute normovolemic hemodilution reduce perioperative allogeneic transfusion? A meta-analysis. The International Study of Perioperative Transfusion. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:9-15.

27 Segal JB, Blasco-Colmenares E, Norris EJ, et al. Preoperative acute normovolemic hemodilution: A meta-analysis. Transfusion. 2004;44:632-644.

28 Ahlberg A, Nillius A, Rosberg B, et al. Preoperative normovolemic hemodilution in total hip arthroplasty. A clinical study. Acta Chir Scand. 1977;143:407-411.

29 Bennett SR. Perioperative autologous blood transfusion in elective total hip prosthesis operations. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1994;76:95-98.

30 Oishi CS, D’Lima DD, Morris BA, et al. Hemodilution with other blood reinfusion techniques in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997:132-139.

31 Lorentz A, Osswald PM, Schilling M, et al. [A comparison of autologous transfusion procedures in hip surgery]. Anaesthesist. 1991;40:205-213.

32 Olsfanger D, Fredman B, Goldstein B, et al. Acute normovolaemic haemodilution decreases postoperative allogeneic blood transfusion after total knee replacement. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:317-321.

33 Ho KM, Ismail H. Use of intravenous tranexamic acid to reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in total hip and knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31:529-537.

34 Cid J, Lozano M. Tranexamic acid reduces allogeneic red cell transfusions in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: Results of a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Transfusion. 2005;45:1302-1307.

35 Gill JB, Rosenstein A. The use of antifibrinolytic agents in total hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:869-873.

36 Zufferey P, Merquiol F, Laporte S, et al. Do antifibrinolytics reduce allogeneic blood transfusion in orthopedic surgery? Anesthesiology. 2006;105:1034-1046.

37 Karkouti K, Beattie WS, Dattilo KM, et al. A propensity score case-control comparison of aprotinin and tranexamic acid in high-transfusion-risk cardiac surgery. Transfusion. 2006;46:327-338.

38 Mangano DT, Tudor IC, Dietzel C. The risk associated with aprotinin in cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:353-365.

39 Brown JR, Birkmeyer NJ, O’Connor GT. Meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness and adverse outcomes of antifibrinolytic agents in cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2007;115:2801-2813.

40 Tylman M, Bengtson JP, Avall A, et al. Release of interleukin-10 by reinfusion of salvaged blood after knee arthroplasty. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:1379-1384.

41 Bottner F, Sheth N, Chimento GF, et al. Cytokine levels after transfusion of washed wound drainage in total knee arthroplasty: A randomized trial comparing autologous blood and washed wound drainage. J Knee Surg. 2003;16:93-97.

42 Cheng SC, Hung TSL, Tse PYT. Investigation of the use of drained blood reinfusion after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective randomised controlled study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2005;13:120-124.

43 Esler CNA, Blakeway C, Fiddian NJ. The use of a closed-suction drain in total knee arthroplasty. A prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:215-217.

44 Tsumara N, Yoshiya S, Chin T, et al. A prospective comparison of clamping the drain or post-operative salvage of blood in reducing blood loss after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:49-53.

45 Majkowski RS, Currie IC, Newman JH. Postoperative collection and reinfusion of autologous blood in total knee arthroplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1991;73:381-384.

46 Heddle NM, Brox WT, Klama LN, et al. A randomized trial on the efficacy of an autologous blood drainage and transfusion device in patients undergoing elective knee arthroplasty. Transfusion. 1992;32:742-746.

47 Newman JH, Bowers M, Murphy J. The clinical advantages of autologous transfusion. A randomized, controlled study after knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79:630-632.

48 Shenolikar A, Wareham K, Newington D, et al. Cell salvage auto transfusion in total knee replacement surgery. Transfus Med. 1997;7:277-280.

49 Thomas D, Wareham K, Cohen D, et al. Autologous blood transfusion in total knee replacement surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:669-673.

50 Zarin J, Grosvenor D, Schurman D, et al. Efficacy of intraoperative blood collection and reinfusion in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2147-2151.

51 Bridgens JP, Evans CR, Dobson PM, et al. Intraoperative red blood-cell salvage in revision hip surgery. A case-matched study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:270-275.

52 Goodnough LT, Despotis GJ, Merkel K, et al. A randomized trial comparing acute normovolemic hemodilution and preoperative autologous blood donation in total hip arthroplasty. Transfusion. 2000;40:1054-1057.

53 Goodnough LT, Monk TG, Despotis GJ, et al. A randomized trial of acute normovolemic hemodilution compared to preoperative autologous blood donation in total knee arthroplasty. Vox Sang. 1999;77:11-16.

54 Woolson ST, Wall WW. Autologous blood transfusion after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, prospective study comparing predonated and postoperative salvage blood. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:243-249.