Chapter 22 What Are the Indications for Surgery, and What Is the Best Surgical Treatment for Chronic Lateral Epicondylitis?

Lateral epicondylitis (LE), or tennis elbow, was first described in the 1880s1 by Major as a condition causing elbow pain in lawn tennis players. Clinically, this entity is characterized by lateral-sided elbow pain with activities of daily living, such as turning knobs and opening jars. Sufferers of LE may also notice a weakness in their grip strength or difficulty carrying objects in their hands.

Physical examination must distinguish between LE and the main differential diagnoses. A cervical examination including nerve root examinations must be done especially if the history is suggestive of cervical pathology. Palpation must be thorough, systematic, and include palpating the radiocapitellar joint for osteoarthritis and the capitellum for osteochondritis dissecans. PIN entrapment tenderness is typically more distal than in LE. Range of motion and stability of the elbow must be tested, including the lateral pivot shift test for posterolateral rotatory instability.2–4

A thorough history and physical examination are usually all that is required for the diagnosis, but radiographs may help to rule out other abnormalities when the diagnosis is doubtful or when history and physical examination suggest coexisting pathologies. In a review of 294 radiographs of patients diagnosed with LE, Pomerance5 found only 16% of patients had positive findings, with the most common abnormality, being faint calcific deposits along the extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) occurring in 7%. In only two cases (0.7%) did radiographs change management plans.

Although ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging have reported sensitivities of 64% to 82% and 90% to 100%, respectively, and specificities of 67% to 100% and 83% to 100%, respectively, they are not traditionally ordered.6

Although up to 40% of tennis players will experience tennis elbow at some point,7 LE is more often seen in workplaces that involve repetitive or forceful activities of the forearm, wrist, or hand.8 In a 31-month study, Kurppa9 found the annual incidence rate in a meat-processing factory housing 377 employees to be 1% for those working in nonstrenuous jobs and 7% to 11% for those working in strenuous jobs. In the general population, Shiri and colleagues8 found the incidence rate of LE to be 1.3% in people aged 30 to 64 years, with a peak incidence in the 45- to 54-year age group in a Finnish study involving 4,783 subjects. Men and women were affected equally.

The precise pathophysiology of LE remains incompletely understood, but the most commonly accepted mechanism appears to be microscopic tearing of the ECRB muscle caused by repetitive trauma.10,11 In up to one third of patients, the extensor digitorum communis (EDC) is also involved. This trauma causes growth of reparative tissue known as angiofibroblastic hyperplasia or angiofibroblastic tendinosis. 11,12 Histologic studies confirm that LE is a misnomer because no inflammatory cells are seen at the time of surgical intervention. A more representative term would be lateral epicondylar tendinosis.

OPTIONS

Although conservative treatment is said to be successful in more than 90% of cases,14 various operations have been described to treat recalcitrant LE. These operations fall into three broad categories: open release, percutaneous release, and arthroscopic release. The best data available on these interventions based on MEDLINE and EMBASE searches are also presented.

EVIDENCE

Acupuncture

Three studies reviewed acupuncture therapy. In a randomized, controlled, double-blind study involving 45 patients, Fink and coauthors15 noticed a significant improvement in maximum grip strength, pain, and function based on the disability of the arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH) form at 2 weeks in the true acupuncture versus sham acupuncture. At 2 months, however, this benefit was no longer seen. In a single blinded, randomized, controlled trial involving 48 patients, Molsberger and Hille16 found acupuncture pain relief superior and longer lasting (20.2 vs. 1.4 hours average) than sham acupuncture. Davidson and coworkers17 compared acupuncture with ultrasound in a study enrolling 16 patients and found significant improvement in both treatments over baseline in DASH scores, pain, and pain-free grip strength but found no significant difference between the two modalities at 1 month. In conclusion, not enough evidence exists to support acupuncture definitively, but studies suggest (grade B) it may have a role in the short term (<6 weeks) only.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Medication

Three randomized, controlled trials on topical NSAIDs versus placebo were done, and meta-analyses were conducted by Green and researchers.18 The trials (Burnham et al., 1998,19 Burton 1988,20 and Jenoure et al., 199721) had a combined population of 130 subjects and assessed the effect of topical NSAIDs (2 trials used diclofenac, 1 trial used difflam) on pain. The pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) was 2 1.88 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2 2.54 to 2 1.21) in the short term (1–3 weeks). That is, those in the topical NSAID group had 1.88 of 10 points less pain on a visual analogue scale (VAS) at the end of the trial than those using placebo.18

Two trials examined oral NSAIDs versus placebo with contradictory results. Labelle and Guibert,22 examining diclofenac daily use for 1 month plus cast immobilization versus immobilization and placebo in a double-blinded, randomized study involving 129 patients, found a significant difference in pain reduction (1.4/10 less pain) but not in grip strength or function in the diclofenac group. The diclofenac group, however, had a greater incidence rate of abdominal pain (30% vs. 9%) and diarrhea (39% vs. 20%) than the placebo group. Hay and investigators,23 examining naproxen use in a study involving 111 randomized patients, however, found no significant difference in improvement in pain after 1 month and 1 year. Side effects were not mentioned in the study.

Corticosteroid Injections

Altay and coauthors,24 in a prospective, randomized trial involving 120 patients, compared injecting triamcinolone with lidocaine to lidocaine alone using the peppering technique (injecting 40–50 times through the same skin entry point) and found no differences in the two groups at 2 months in the number of excellent results defined as complete pain relief, completely satisfied and devoid of pain on resisted wrist dorsiflexion (93% in the triamcinolone arm vs. 95% in the control group). Results were not changed at 6 months or 1 year.

Smidt and researchers25 compared physiotherapy with corticosteroid injection with a wait-and-see approach in a randomized, controlled trial involving 185 patients. Exclusion criteria included physiotherapy treatment or injections for the elbow complaint in the last 6 months. Corticosteroid injections consisted of 1 mL triamcinolone (10 mg/mL) and 1 mL 2% lidocaine injected into all painful areas until resisted dorsiflexion was no longer painful. A maximum of 3 injections over a 6-week period were allowed. Fifty-eight percent (58%) used one injection, 27% used two, and 15% used three. The physiotherapy consisted of nine treatments of pulsed ultrasound, deep friction massage, and a home exercise program over 6 weeks. The waitand-see group was educated on the disease and how to avoid provoking pain. All groups were told to avoid aggravating activities, discouraged from using other forms of treatment but allowed pain medication (naproxen [Naprosyn] and paracetamol). Patients kept a diary of other forms of treatments used, but activity level was not recorded. Success was defined as pain completely resolved or much improved. The researchers also reviewed patient self-rated general improvement, severity of the main complaint, pain, elbow disability, and patient satisfaction. Severity of elbow complaint, grip strength, and pressure pain threshold were assessed by a research physiotherapist.

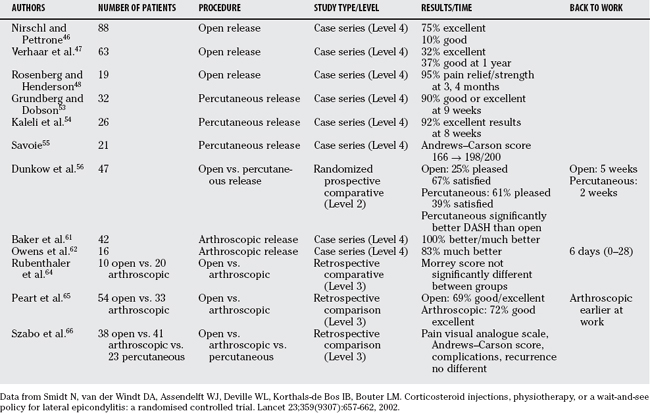

As shown in Figure 22-1, at 6 weeks, corticosteroids had significantly greater success rate (92%) than both physiotherapy (47%) and wait-and-see (32%) approaches, but this was no longer true at 3 months. The corticosteroid injection group had a greater relapse rate (defined as no longer completely resolved or much improved) at 72% than the physiotherapy and wait-and- see groups (at 8% and 9%, respectively). At 1 year, the injection group had a lower success rate (69%) than both the physiotherapy (91%) and the wait-and-see (83%) groups.

FIGURE 22-1 Success rates of three treatment regiment.

(Adapted from Smidt N, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, Deville WL, Korthals-de Bos IB, Bouter LM. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 23;359[9307]:657-662, 2002 with permission of Elsevier.)

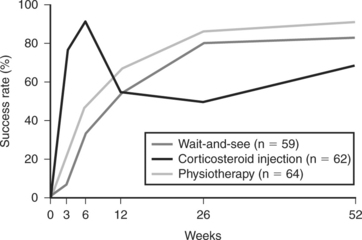

Bisset and colleagues26 also compared corticosteroid injections to physiotherapy to a wait-and-see approach in a single-blinded, randomized, controlled trial involving 198 participants with follow-up of 1 year. Participants had symptoms of LE for more than 6 weeks. Exclusion criteria included any treatment for LE by any health practitioner in the last 6 months. The corticosteroid injection group received 1 mL triamcinolone (10 mg/mL) and 1 mL of 1% lidocaine to painful elbow points. A second injection was allowed at 2 weeks if needed. Eighty-six percent received one injection, whereas 12% received two and 1.5% (one patient) received three. Physiotherapy consisted of eight sessions of elbow manipulations and exercises over a 6-week period. All patients were given an information booklet outlining the disease process and providing practical advice on selfmanagement and ergonomics. A diary recording any other forms of treatment was kept. Analgesics were allowed, but other treatment modalities were discouraged. Primary end points were global improvement scale where completely resolved or much improved were deemed successful, pain-free grip strength as a percentage of normal side, and assessor’s rating of severity. As shown in Figure 22-2, at 6 weeks, corticosteroid injections were significantly better in all 3 end points, having 78% success rate compared with 65% in the physiotherapy group and 27% in the wait-and-see group. At 3 months, however, this was reversed, with the injection group having only 45% success as opposed to 76% success with physiotherapy or 59% with the wait-and-see approach. This relation was maintained at 1 year, with the corticosteroid group having less success (68%) compared with the physiotherapy group at 94% success and the wait-and-see group at 90% success.

FIGURE 22-2 Primary outcome measure: mean assessor’s rating of severity (visual analog scale), mean pain-free grip (PFG— affected/unaffected expressed as a percentage), and percentage success. Significant differences between study arms at 6 and 12 weeks: †corticosteroid injection versus wait-and-see approach; ‡physiotherapy versus wait-and-see approach; §corticosteroid injection versus physiotherapy; ¶significant difference between corticosteroid and wait-and-see approach on per protocol analysis. Bar graphs represent mean (99% confidence interval) area under curve (trapezium method24) analysis of assessor severity, PFG, and global improvement. *Significant differences between groups (P <0.01).

Adapted from Bisset L, Beller E, Jull G, Brooks P, Darnell R, Vicenzino B. Mobilisation with movement and exercise, corticosteroid injection, or wait and see for tennis elbow: randomised trial. BMJ 333(7575):939, 2006 with permission of the BMJ Publishing Group.

Area under the curve analysis demonstrated a significant advantage in favor of physiotherapy over injection for all primary outcome measures and over wait and see for pain-free grip (mean difference [MD], 534; 99% CI, 3–1065) and assessor-rated severity (MD, 447; 99% CI, 137–758). It also demonstrated a significant advantage for wait and see over injection for global improvement (MD, 2 8.3; 99% CI, 2 15.0 to 2 1.5) and assessor-rated severity (2 337; 99% CI, 2 642 to 2 32).26

Physiotherapy

Two studies (see Corticosteroid Injections earlier in chapter) reviewed physiotherapy versus a waitand-see approach25,26 and had conflicting results. Smidt and researchers25 found nine treatments of pulsed ultrasound, deep friction massage, and a home exercise program over 6 weeks to be better than wait and see over the short and long term but not by a significant amount. Wait and see also had more patients not use any other forms of treatment (79%) than the physiotherapy group (19%). If one excludes physiotherapy done within 6 weeks of the end of the treatment period, however, both groups have similar percentages of patients not using any other forms of treatments (85% in the physiotherapy group and 83% in the wait-and-see group).

Bisset and colleagues26 found eight sessions of elbow manipulations combined with an exercise program for 6 weeks was favorable over wait and see at 6 weeks in terms of the number of patients with complaints completely resolved or much improved, pain-free grip strength and assessor-rated severity but no longer at 1 year. Furthermore, more of the patients in the physiotherapy group used no other forms of treatment (79%) versus 45% in the wait-and-see group.

Smidt and researchers’25 and Bisset and colleagues’26 studies give the closest approximation of the natural history of LE to date. In both studies, more than 80% of patients had symptoms that were much improved or completely resolved by 6 months with little or no treatment beyond activity modification and patient education.

Brace

Faes and investigators27 compared a dynamic extensor brace (Carp-x; Somas, St-Anthonis, Netherlands) with no brace in a randomized, controlled trial involving 63 patients and found significant differences favoring the brace group in pain, pain-free maximum grip strength, and function of the arm at 12 and 24 weeks. In that article, graphs are presented but no numbers are given.

Jensen and coworkers28 compared an off-the-shelf orthotic (Rehband) with corticosteroid injections in 30 randomized patients over a period of 6 weeks and found no significant differences between the groups in pain, maximum grip strength, dumbbell test, function VAS, or global improvement.29 Similarly, Erturk and colleagues30 compared an epicondylitis bandage with a steroid injection in 36 randomized patients and found no significant difference at 3 weeks in pain on resisted wrist extension and no difference in maximum grip strength. Haker and Lundeberg,31 in a study involving 61 patients, compared an elbow strap and a wrist splint with corticosteroid injections looking at global function and pain-free grip strength, and found improved global function with the injection group at 2 weeks but no difference in pain-free grip strength. No differences were found between the groups at 6 months or at 1 year.

Dwars and researchers32 compared the Epitrain orthosis with physiotherapy (unspecified) looking at pain and global function in a randomized study involving 84 patients, and found no significant differences. Struijs and colleagues33 compared an elbow strap brace (Epipoint) to physiotherapy (pulsed ultrasound, friction massage, and strengthening and stretching exercises) to the Epipoint brace plus physiotherapy in a randomized trial involving 180 patients looking at 9 outcomes (global function, severity of the patient’s complaints, severity of the patient’s main complaint, modified pain-free function questionnaire [PFFQ], inconvenience during daily activities, pain-free grip strength, maximal grip strength, pressure pain, and satisfaction). Over the short term (6 weeks), combination therapy was superior over bracing alone in severity of complaints (MD, 11/100; 95% CI, 6–18), PFFQ (MD, 9; 95% CI, 2–15), and satisfaction (MD, 11; 95% CI, 3–19), but not in the other 6 outcomes measured. Combination treatment offered little or no benefit over physical therapy alone. Physical therapy and bracing also fared similarly. Over the mid term (26 weeks) and long term (1 year), all three groups scored similarly with no significant differences in any of the 9 outcomes measured.

Bracing may help in LE but there is insufficient data to promote or refute it’s use.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy

Nine randomized, controlled trials were found comparing ESWT against placebo with conflicting results. Three studies34–36 favored ESWT over placebo, whereas four trials38–41 showed no advantage to ESWT. When available data from the trials were pooled by Buchbinder and coauthors,37 however, most benefits observed in the positive trials were no longer statistically significant.

Data from 6 trials could be pooled, and based on these data, most of the evidence supports the conclusion that ESWT is no more effective than placebo for lateral elbow pain. For example, pooled analysis of 3 trials (446 participants)34,38, 39 showed that ESWT is no more effective than placebo with respect to pain at rest at 4 to 6 weeks after the final treatment (WMD pain out of 100 = −9.42 [95% CI, −20.70 to 1.86]); pooled analysis of three trials (455 participants)35–38 (Pettrone, 2005) showed that ESWT is no more effective than placebo at 12 weeks after the final treatment with respect to pain provoked by resisted wrist extension (Thomsen test) (WMD pain out of 100 = −9.04 [95% CI, −19.37 to 1.28]) and grip strength (SMD [standardized mean difference], 0.05 [95% CI, −0.13 to 0.24]).

Pooled analyses combining results of other trials failed to demonstrate statistically significant benefits for ESWT over placebo across a range of outcomes including mean pain with resisted middle-finger extension or resisted wrist extension at 6 weeks after completion of treatment, night pain at 3 to 4 weeks after completion of treatment, or failure of treatment defined by a Roles and Maudsley score of 4 at 6 weeks and 12 months after completion of treatment.38,39, 41 Based on these studies and their pooling,37 good evidence (grade A) exists to refute the use of ESWT for treating LE.

Botulinum (Botox) Injection

Wong and colleagues42 compared Botox A injection (1 cm distal to the epicondyle) with normal saline injection in a randomized, double-blinded, controlled study involving 60 patients with symptoms of LE for at least 3 months looking at pain VAS and grip strength. Exclusion criteria included having received any corticosteroid injection. Significant differences in improvement in pain between the groups of 24.4 mm at 4 weeks and 19.3 mm at 12 weeks favoring Botox were found. Significant grip strength improvement was present in both groups but not significantly different between the groups. Mild paresis of the fingers occurred in 4 (13%) patients in the botulinum group at 4 weeks. One patient’s (3%) symptoms persisted until week 12, whereas none of the patients receiving placebo had the same complaint. At 4 weeks, 10 patients (33%) in the botulinum group and 6 patients (20%) in the placebo group experienced weak finger extension on the same side as the injection site. At 12 weeks, 2 patients in the Botox group (7%) and 1 patient (3%) in the placebo group still reported weak finger extension.

Placzek and coauthors43 studied Botox injection (0.6 mL 3–4cm distal to epicondyle tender region) versus placebo (normal saline injection) in a randomized, controlled, double-blinded clinical trial involving 130 patients with follow-up at 2, 6, 12, and 18 weeks, and found modest improvements with the Botox group. Continuous pain VAS in the last 48 hours was significantly better for Botox than for placebo at 6 and 18 weeks, but not at 2 and 12 weeks. The MD was 1.14 (out of 10) at 6 weeks and 0.86 at 18 weeks. Maximum pain VAS in the last 48 hours, however, was not significantly better between the groups at any time point. Global assessment rated by the physician and global assessment as rated by the patient, where 4 was substantially better, 3 was slightly better, 2 was unchanged, 1 was slightly worse, and 0 was substantially worse, were significantly better from 6 weeks onward for the Botox group. The MDs in patient global assessment are 0.56, 0.31, and 0.55 at 6, 12, and 18 weeks, respectively. At 18 weeks, the greatest mean scores for both groups were 3.31 for the Botox group and 2.76 for the placebo group. As a side effect, the Botox group experienced significant decrease in third finger extension strength compared with the control group starting at 2 weeks. By 12 weeks, the strength was back to preinjection levels, and by 18 weeks, the difference between the groups was no longer significant. Wrist extension and grip strength was not significantly different between the groups.

Keizer and coworkers44 compared Botox injection into ECRB muscle with surgical extensor release as described by Hohmann in a randomized prospective study involving 40 patients and follow-up at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months. At 1 year, the number of patients with good to excellent results were similar; namely, 65% in the Botox group and 75% in the operative group.

Hayton and coauthors45 had different results, however, comparing Botox A injections (2 mL 5 cm distal to tender region of epicondyle) with normal saline injections in 40 patients in a double-blinded study. Inclusion criteria included symptoms for at least 6 months and having received at least one corticosteroid injection. At 3 months, there were no significant differences found in pain VAS, Short Form 12 (SF-12) scores, or grip strength. Two of 18 patients in the Botox group experienced third finger extension weakness that interfered with their quality of life.

Several reasons may explain the different results obtained in Hayton and coauthors’45 study from Wong and colleagues’42 and Placzek and coauthors’43 studies. First, at 40 patients (vs. 60 and 130), perhaps Hayton and coauthors’45 study lacks the necessary power to detect a significant benefit to the Botox injection. Second, all patients in Hayton and coauthors’45 study had received corticosteroid injections, whereas only some in Placzek and coauthors’43 and none in Wong and colleagues’42 study had received any. Perhaps the tendon degeneration that may occur with corticosteroid injection blunts the beneficial effect that the Botox-induced rest provides.

Surgery

Open Surgery.

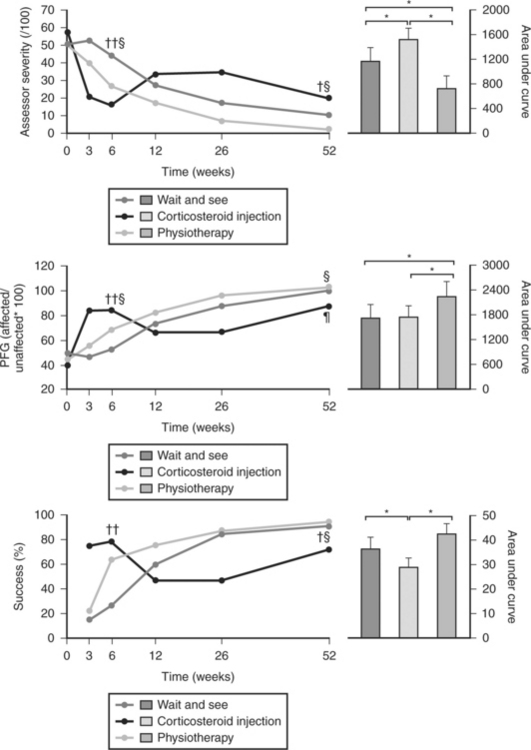

Table 22-1 outlines the results of various studies on surgical lateral release for LE.

Nirschl and Pettrone46 described a technique in 1979 where the interval between ECRL and EDC is utilized through a 2.5-cm skin incision to expose and resect the diseased ECRB tendon. In this technique, the joint is not routinely inspected, any diseased EDC is also resected, and one to two holes are drilled in the exposed lateral humeral condyle to enhance bleeding and healing. With this technique, Nirschl and Pettrone46 achieved 75% excellent results and 10% good results in 88 elbows. There was an improvement rate of 97.7% and 85% returned to full activities.

Verhaar and researchers47 in a prospective study reported somewhat worse results, with 76% of their 63 cases having no or slight pain at 1 year after surgery. At 1 year, there were 32% excellent results, 37% good results, 19% fair results, and 11% poor results. At 5 years, there were 32 excellent results (56%), 19 good results (33%), 4 fair results (7%), and 2 poor results (4%).

Rosenberg and Henderson48 reported on open lateral releases in 19 patients, with 95% achieving pain relief and strength gain, on average, 3 and 4 months after surgery, respectively.

Khashaba49 questioned the need for drilling the lateral condyle in a randomized, single-blinded trial involving 23 elbows where the lateral epicondyle was drilled in half of the cases and no drilling was performed in the other half looking at subjective pain and objective wrist extension strength at 3 and 6 months. Despite this article’s results being cited in many other publications50,51 and the article being a single-blinded randomized trial, the article’s presentation makes it difficult to know whether the findings are backed by rigorous method. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are not clearly defined. No mention is made of the comparability of the two arms before surgery (age, duration of symptoms, number of corticosteroid injection, etc.). No P values, no standard deviations, and no confidence intervals are indicated. Postoperative pain is compared with remembered preoperative pain at 3 and 6 months instead of pain documented before surgery. The only numbers mentioned are the average increase in power at 6 months (3 months not indicated), and these are 5.2 kg in the drilled group versus 6.5 kg in the nondrilled group. Average decrease in pain (3 and 6 months combined and averaged) was 4.6 of 10 in the drilled group versus 6.8 of 10 in the nondrilled group.

Percutaneous Lateral Release.

In 1933, Hohmann52 described epicondylar stripping done percutaneously for LE with good success. More recently, Grundberg and Dobson53 reported on results from percutaneous common extensor release in 32 elbows that had been having symptoms for, on average, 18 months. Ninety percent (90%) had excellent or good results, with the pain relieved, on average, 9 weeks after operation. Grip strength improved from an average of 60% of the opposite side to 90% after operation. Kaleli and investigators54 investigated 26 patients with symptoms of LE for an average of 8.9 months before having a percutaneous extensor release and found excellent results in 92% of cases, with pain relief coming, on average, 8 weeks after surgery.

In the percutaneous release described by Savoie,55 a #11 blade knife is introduced 2 to 3 mm anterior to the epicondyle with the elbow flexed at 90 degrees. The blade inserted parallel to the long axis of the humerus is then pivoted so that its tip reaches the more superior aspect of the ECRB proximally. Distally, the blade tip stops short of the articular margin of the humerus. The surgeon’s thumb is kept on the posterolateral aspect of the radiocapitellar joint to protect the radial collateral ligament. A small rasp is then used to excoriate the epicondyle in the area to stimulate a healing response. Using this technique, Savoie55 had an average increase of 32 in Andrews–Carson scores in 21 percutaneous releases after surgery, obtaining an average score of 198 out of 200. A high Andrews–Carson score indicates good function.

One advantage of a percutaneous release over the open release is lower morbidity. Dunkow and colleagues56 conducted a randomized trial comparing an open release with a percutaneous release in 47 elbows of patients with unsuccessful results after 1 year of conservative treatment and found the percutaneous release group returned to work at an average of 2 weeks after surgery, 3 weeks earlier than the open group (P 5 0.001). Furthermore, the decrease in DASH score after surgery showing improved function was significantly larger in the percutaneous release group. In addition, 50% of patients were pleased with procedure in the percutaneous group versus 25% in the open group.

One disadvantage of the percutaneous release compared with the open release may be inability to resect all the degenerative pathology. Organ and coworkers57 reviewed 35 cases of failed lateral releases with the distribution of the most recent techniques as follows: 19 slide and release procedures, 6 slide and release procedures with partial resection of the annular ligament (Bosworth), 7 unknown surgical interventions, 2 primary radial nerve decompressions, and 1 Nirschl procedure. In 27 elbows, the pathologic changes in the ECRB tendon had not been previously addressed at all, and in 7 elbows, the damaged tissue had not been completely excised. Salvage surgery included excision of pathologic tissue in the ECRB tendon origin combined with excision of excessive scar tissue and repair of the extensor aponeurosis when necessary. Based on a 40-point functional rating scale proposed here, 83% of the elbows (29/35) had good or excellent results at an average follow-up of 64 months (range, 17 months to 17 years).

Arthroscopic Lateral Release.

In 1995, Grifka and colleagues58 described an arthroscopic method of doing a Hohman lateral release for recalcitrant tennis elbow. Kuklo and researchers59 conducted a cadaveric study using 10 specimens to study the safety of the lateral arthroscopic release. He found the radial nerve to be in close proximity to the proximal lateral portal (average, 5.4 mm), but failed to find instability in the elbow after intervention. Smith and investigators60 confirmed the efficacy of the arthroscopic procedure using seven cadavers. They note that the ECRB and EDC origin was resected a mean of 100% and 90%, respectively. Elbow stability was maintained when resection did not extend posteriorly to an intra-articular line bisecting the radial head. Arthroscopy also allows for a faster recovery than open releases in theory. Furthermore, intra-articular pathology can be addressed concomitantly.

Baker and coauthors61 published their results in 42 arthroscopic releases. Patients had, on average, 14 months of symptoms prior to the release and were followed for an average of 2.8 years after the procedure. The average pain at rest after surgery was 0.9 out of 10, pain with daily activity was 1.4, and pain with sport was 1.9. Of the 39 elbows in the 37 patients who were available for follow-up, 37 were rated “better” or “much better.” Patients returned to work in an average of 2.2 weeks. Grip strength averaged 96% of the strength of the unaffected limb. Notably, there was a 69% rate of associated intra-articular pathologies found at the time of arthroscopy. Owens and colleagues,62 in a case series of 16 arthroscopic ECRB releases in patients with symptoms lasting for an average of 31.7 months, found 83% of cases to be much better, with an average pain with activities of daily living of 1.58 out of 10 and an average return to unrestricted work in 6 days (range, 0–28 days).

Cohen et al. (unpublished data; however, work is incorrectly cited as published in Cohen and colleagues63) compared open with arthroscopic releases in a study involving 30 patients. They conclude that there were no differences between the two procedures regarding outcomes, return of strength, and postoperative symptoms. However, the arthroscopic group returned to sports and work much sooner, at 35 versus 66 days after the open surgery. Rubenthaler and investigators64 compared retrospectively open lateral Hohmann releases (10 cases) with arthroscopic (20 cases) Hohmann lateral releases and found similar results in the 2 groups. The score of Morrey showed an average scoring of 93.2 for the endoscopic group and 87.5 for the open group (P >0.05). Peart and coworkers65 retrospectively compared 54 open lateral releases with 33 arthroscopic ones and found no significant differences in outcomes. Sixty-nine (69%) of open cases and 72% of arthroscopic cases had good or excellent outcomes. Notably, patients treated with arthroscopic release returned to work earlier than patients treated with open release, and required less postoperative therapy.

Szabo and coauthors66 retrospectively reviewed 38 open lateral release cases, 41 arthroscopic cases, and 23 percutaneous cases. The groups were matched for age, sex, dominance, conservative measures used, cortisone injections, and preoperative pain VAS scores, but the percutaneous cases had a better preoperative Andrews–Carson score at 164.6 (vs. 160.2 for open and 158.9 for arthroscopic) and a shorter duration of conservative care (6.6 months for percutaneous vs. 15.3 for open cases and 12.9 for arthroscopic cases). Possibly confounding the interpretation of the data, however, more than one procedure was performed in many cases. In the arthroscopic release group, 44% had intra-articular pathology addressed at the time of arthroscopy, consisting of 14 plicae, 2 loose bodies, and 2 posterolateral ligamentous repairs. Twenty-two (22%) arthroscopic cases also had extra-articular procedures performed, consisting of 5 posterior interosseous nerve releases, 2 carpal tunnel releases, and 2 open posterolateral ligamentous reconstructions. Approximately 21.1% of the open group had other procedures performed consisting of three shoulder arthroscopies, two ulnohumeral arthroplasties, two posterior interosseous nerve releases, and one carpal tunnel release. It is noted that when these procedures and their possible influence on the postoperative Andrews–Carson score were examined, no difference was found, but no data is given. Nevertheless, Szabo and coauthors66 found that postoperative pain VASs, Andrews–Carson scores, number of complications, failures, and recurrences were not significantly different for the 3 groups. The Andrews–Carson score was 195.3, 195.4, and 193 for open, arthroscopic, and percutaneous groups, respectively.

A need exists for better studies on surgical interventions. Only the study by Keizer and coworkers,44 which prospectively compared Botox injections with a Hohmann open release, has prospectively compared surgery with a conservative measure. Only one study conducted by Dunkow and colleagues56 has compared one surgical technique with another in a randomized prospective manner. It is thus difficult to make conclusive statements about the value of surgical interventions over certain less invasive conservative measures or the value of one technique over another. The evidence suggests, however, that all three techniques—open, percutaneous, and arthroscopic releases—are effective in treating recalcitrant LE. It would also seem percutaneous and arthroscopic releases lead to a quicker return to activities after surgery than do open surgeries.

LE is usually a self-limiting disease. More than 80% of patients have symptoms that are completely resolved or much better by 6 months with little treatment when aggravating activities are avoided for 6 weeks and the patient is educated.

Failure of conservative treatment for more than 6 months warrants surgical intervention. Earlier surgical intervention may be warranted if symptoms are incapacitating. Although open, percutaneous, and arthroscopic lateral releases are acceptable options, we favor arthroscopic release. Arthroscopic release allows inspection and treatment of joint pathology, leads to good pain relief and strength gain, and returns the patients quicker to work. Table 22-2 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of LE.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Major HP. Lawn-tennis elbow. Br Med J. 1883;2:557.

2 Murphy KP, Giuliani JR, Freedman BA. Management of lateral epicondylitis in the athlete. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2006;14:67-74.

3 Mehta JA, Bain GI. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2004;12:405-415.

4 O’Driscoll SW, Bell DF, Morrey BF. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:440-446.

5 Pomerance J. Radiographic analysis of lateral epicondylitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:156-157.

6 Miller TT, Shapiro MA, Schultz E, Kalish PE. Comparison of sonography and MRI for diagnosing epicondylitis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30:193-202.

7 Bisset L, Paungmali A, Vicenzino B, Beller E. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials on physical interventions for lateral epicondylalgia. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:411-422.

8 Shiri R, Viikari-Juntura E, Varonen H, Heliovaara M. Prevalence and determinants of lateral and medial epicondylitis: A population study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164:1065-1074.

9 Kurppa K, Viikari-Juntura E, Kuosma E, et al. Incidence of tenosynovitis or peritendinitis and epicondylitis in a meat-processing factory. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1991;17:32-37.

10 Cyriax JH. The pathology and treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg. 1936;18:921-940.

11 Kraushaar BS, Nirschl RP. Tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow). Clinical features and findings of histological, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopy studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:259-278.

12 Regan W, Wold LE, Coonrad R, Morrey BF. Microscopic histopathology of chronic refractory lateral epicondylitis. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:746-749.

14 Coonrad RW, Hopper WR. Tennis elbow: It’s course, natural history, conservative and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55:1177-1182.

15 Fink M, Wolkenstein E, Karst M, Gehrke A. Acupuncture in chronic epicondylitis: A randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2002;41:205-209.

16 Molsberger A, Hille E. The analgesic effect of acupuncture in chronic tennis elbow pain. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33:1162-1165.

17 Davidson J, Vandervoort A, Lessard L, et al. The effect of acupuncture versus ultrasound on pain level, grip strength and disability in individuals with lateral epicondylitis: A pilot study. Physiother Can. 2001;53:195-202. 211

18 Green S, Buchbinder R, Barnsley L, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for treating lateral elbow pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.; 2; 2002; CD003686.

19 Burnham R, Gregg R, Healy P, Steadward RL. The effectiveness of topical diclofenac for lateral epicondylitis. Clin J Sports Med. 1998;8:78-81.

20 Burton A. A comparative trial of forearm strap and topical anti-inflammatory as adjuncts to manual therapy in tennis elbow. Man Med. 1988;3:141-143.

21 Jenoure P, Rostan A, Gremion G, et al. Multi-centre, double-blind, controlled clinical study on the efficacy of diclofenac epolamine tissugel plaster in patients with epicondylitis. Medicina Dello Sport. 1997;50:285-292.

22 Labelle H, Guibert R. Efficacy of diclofenac in lateral epicondylitis of the elbow also treated with immobilization. Arch Fam Med. 1997;6:257-262.

23 Hay E, Paterson S, Lewis M, et al. Pragmatic randomised controlled trial of local corticosteroid injection and naproxen for treatment of lateral epicondylitis of elbow in primary care. BMJ. 1999;319:964-968.

24 Altay T, Gunal I, Ozturk H. Local injection treatment for lateral epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 398; 2002; 127-130.

25 Smidt N, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, et al. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lateral epicondylitis: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:657-662.

26 Bisset L, Beller E, Jull G, et al. Mobilisation with movement and exercise, corticosteroid injection, or wait and see for tennis elbow: Randomised trial. BMJ. 2006;333:939.

27 Faes M, van den Akker B, de Lint JA, et al. Dynamic extensor brace for lateral epicondylitis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;442:149-157.

28 Jensen B, Bliddal H, Danneskiold-Samsore B. Comparison of two different treatments of lateral humral epicondylitis—“tennis elbow.” A randomized controlled trial (in Danish). Ugeskr Laeger. 2001;163:1427-1431.

29 Struijs PA, Smidt N, Arola H, et al. Orthotic devices for tennis elbow. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.; 2; 2001; CD001821.

30 Erturk H, Celiker R, Sivri A, et al. The efficacy of different treatment regiments that are commonly used in tennis elbow [Tenisci dirseginde sik kullanilan farkli tedavi yaklasimlarinin etkinligi]. J Rheum Med Rehab. 1997;8:298-301.

31 Haker E, Lundeberg T. Elbow-band, splintage and steroids in lateral epicondylalgia (tennis elbow). Pain Clinic. 1993;6:103-112.

32 Dwars BJ, de Feiter P, Patka P, Haarman HJThM. Functional treatment of tennis elbow. In: Hermans G, editor. Proceedings of the 24th world congress of Sports Medicine, 1990. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers (Biomedical Division); 1990:237-241.

33 Struijs PA, Kerkhoffs GM, Assendelft WJ, Van Dijk CN. Conservative treatment of lateral epicondylitis: Brace versus physical therapy or a combination of both—a randomized clinical trial. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:462-469.

34 Rompe J, Hopf C, Kullmer K, et al. Low-energy extracorporeal shock-wave therapy for persistent tennis elbow. Int Orthop. 1996;20:23-27.

35 Rompe JD, Decking J, Schoellner C, Theis C. Repetitive low-energy shock wave treatment for chronic lateral epicondylitis in tennis players. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:734-743.

36 Petronne FA, McCall BR. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy without local anesthesia for chronic lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2005;87(6):1297-1304.

37 Buchbinder R, Green SE, Youd JM, et al. Shock wave therapy for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.; 4; 2005; CD003524.

38 Haake M, Boddeker IR, Decker T, et al. Side effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in the treatment of tennis elbow. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:222-228.

39 Speed C, Nichols D, Richards C, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy for lateral epicondylitis—a double blind randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:895-898.

40 Melikyan EY, Shahin E, Miles J, Bainbridge LC. Extracorporeal shock-wave treatment for tennis elbow. A randomised double-blind study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:852-855.

41 Chung B, Wiley JP. Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy in the treatment of previously untreated lateral epicondylitis: A randomised controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1660-1667.

42 Wong SM, Hui AC, Tong PY, et al. Treatment of lateral epicondylitis with botulinum toxin: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:793-797.

43 Placzek R, Drescher W, Deuretzbacher G, et al. Treatment of chronic radial epicondylitis with botulinum toxin A. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:255-260.

44 Keizer SB, Rutten HP, Pilot P, et al. Botulinum toxin injection versus surgical treatment for tennis elbow: A randomized pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 401; 2002; 125-131.

45 Hayton MJ, Santini AJ, Hughes PJ, et al. Botulinum toxin injection in the treatment of tennis elbow. A double-blind, randomized, controlled, pilot study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:503-507.

46 Nirschl RP, Pettrone FA. Tennis elbow. The surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:832-839.

47 Verhaar J, Walenkamp G, Kester A, et al. Lateral extensor release for tennis elbow. A prospective long-term follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1034-1043.

48 Rosenberg N, Henderson I. Surgical treatment of resistant lateral epicondylitis. Follow-up study of 19 patients after excision, release and repair of proximal common extensor tendon origin. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2002;122:514-517.

49 Khashaba A. Nirschl tennis elbow release with or without drilling. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:200-201.

50 Whaley AL, Baker CL. Lateral epicondylitis. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23:677-691. x

51 Murphy KP, Giuliani JR, Freedman BA: Management of lateral epicondylitis in the athlete. Oper Tech Sports Med 14:67–74.

52 Hohmann G. Das wesen und die behandlung des sogenannten tennisellenbogens (the nature and treatment of so-called tennis elbow). Much Med Wochnschr. 1999;80:250-252.

53 Grundberg AB, Dobson JF. Percutaneous release of the common extensor origin for tennis elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 376; 2000; 137-144.

54 Kaleli T, Ozturk C, Temiz A, Tirelioglu O. Surgical treatment of tennis elbow: Percutaneous release of the common extensor origin. Acta Orthop Belg. 2004;70:131-133.

55 Savoie FH. Management of lateral epicondylitis with percutaneous release. Tech Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;2:243-246.

56 Dunkow PD, Jatti M, Muddu BN. A comparison of open and percutaneous techniques in the surgical treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:701-704.

57 Organ SW, Nirschl RP, Kraushaar BS, Guidi EJ. Salvage surgery for lateral tennis elbow. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:746-750.

58 Grifka J, Boenke S, Kramer J. Endoscopic therapy in epicondylitis radialis humeri. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:743-748.

59 Kuklo TR, Taylor KF, Murphy KP, et al. Arthroscopic release for lateral epicondylitis: A cadaveric model. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:259-264.

60 Smith AM, Castle JA, Ruch DS. Arthroscopic resection of the common extensor origin: Anatomic considerations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:375-379.

61 Baker CLJr, Murphy KP, Gottlob CA, Curd DT. Arthroscopic classification and treatment of lateral epicondylitis: Two-year clinical results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:475-482.

62 Owens BD, Murphy KP, Kuklo TR. Arthroscopic release for lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:582-587.

63 Cohen M, Romeo A. Lateral epicondylitis: Open and arthroscopic treatment. J Am Soc Surg Hand. 2001;1:172-176.

64 Rubenthaler F, Wiese M, Senge A, et al. Long-term follow-up of open and endoscopic Hohmann procedures for lateral epicondylitis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:684-690.

65 Peart RE, Strickler SS, Schweitzer KMJr. Lateral epicondylitis: A comparative study of open and arthroscopic lateral release. Am J Orthop. 2004;33:565-567.

66 Szabo SJ, Savoie FH3rd, Field LD, et al. Tendinosis of the extensor carpi radialis brevis: An evaluation of three methods of operative treatment. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15:721-727.