Chapter 85 What Are the Facts and Fiction of Minimally Invasive Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Surgery?

Although minimally invasive surgical (MIS) techniques such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy and arthro-scopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction have gained widespread acceptance in the surgical community, reduced invasiveness in total joint replacement has stirred much controversy and debate. The concept of minimizing iatrogenic trauma has always been a fundamental surgical principle. However, it is only recently that the concept of small-incision surgery and minimal musculotendinous disturbance has come to the forefront in the total hip and total knee arthroplasty (THA and TKA) literature, the lay press, and commercial advertising.

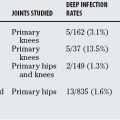

Advocates for MIS joint replacement proclaim the benefits of less blood loss, less postoperative pain, reduced length of hospital stay, more rapid recovery of function, and better cosmesis without increased risk for complication or diminished duration of implant survivorship.1–11 However, other investigators have failed to find significant benefit from MIS joint replacement and have encountered steep and difficult learning curves.10,12–18 Some investigators have discovered concerning rates of serious complications such as implant malposition, intraoperative fracture, skin complications, and prolonged operative durations.18–24 These data combined with the well-documented and highly favorable long-term results of traditional-incision joint replacement have resulted in some vocal opposition to the placement of excessive emphasis on incision length.25–27 Some authors have questioned the ethics of the broad application of such techniques without proven benefit, as well as the role that direct-to-consumer advertising and commercial interests have played before thorough study.28–30

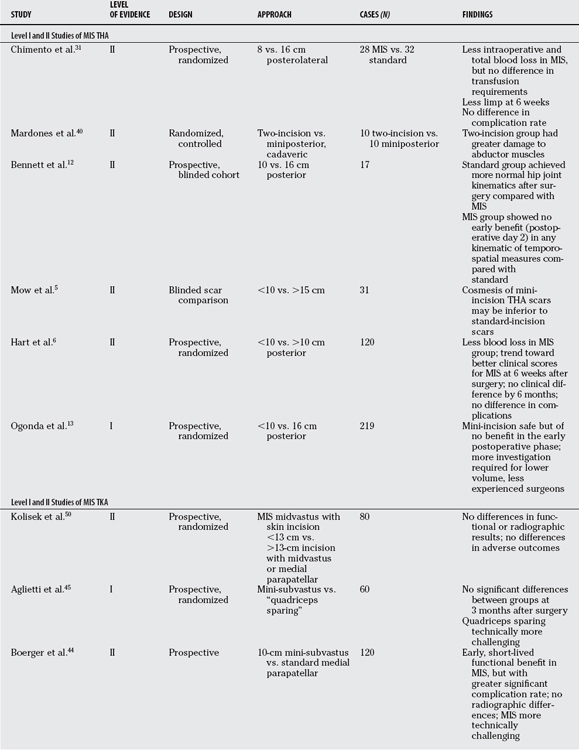

The purpose of this chapter is to review the available evidence in the literature that is capable of directing potential incorporation of novel MIS techniques into the already successful practice regimens of hip and knee arthroplasty, which have been developed over more than three decades. Techniques that involve smaller and modified implant plant components such as unicompartmental knee arthroplasty or resurfacing of the hip are not considered here. Although the overwhelming majority of data on this topic is derived from retrospective cohort studies and case–control series, there is a modest amount of Level I and II evidence available to draw some conclusions and make practice recommendations (Tables 85-1 and 85-2).

TABLE 85-2 Summary of Recommendations

OPTIONS

Hip

In MIS hip surgery, the dominant approaches have been modifications of standard anterior, posterior, and lateral surgical exposures, as well as a combined anterior and posterior approach commonly called the “two-incision” technique. This has led to the development of surgical instrument systems that are smaller and of lower profile, but the actual implants themselves have not changed in any significant way. The posterior technique of mini-incision THA has been described by authors such as Chimento and coworkers.31 This approach involves an incision of 6 to 10 cm in length without disruption of the gluteus maximus tendon or the quadratus femoris muscle. Berger1 has described an anterolateral approach that transects less gluteus medius and minimus through an 8- to 10-cm incision. Toms and Duncan32 have published a description of a single incision intermuscular anterolateral approach that they claim has advantages of standard lateral patient positioning, simple conversion to an extensile approach, no need for fluoroscopy, and a short learning curve for surgeons.

Among the most controversial novel hip approaches has been the two-incision method written about extensively by Berger.33 It has been claimed that this technique is completely intermuscular and “avoids the transection of any muscle or tendon.”1 The two-incision technique utilizes an anterior, Smith–Peterson interval for the acetabular exposure, and a posterior incision between the abductors and the external rotators for stem insertion. The described technique requires intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging.

Knee

Three modifications of standard techniques have gained wider utilization in the knee, as well as one novel approach, which has much less general acceptance. All four techniques have in common abandonment of the formerly common practice of patellar eversion and tibiofemoral dislocation for exposure purposes.34 They also make use of the concept of “mobile windows” of exposure that utilize varying degrees of flexion and extension throughout the procedure to allow visualization of the femur or the tibia, but not both simultaneously.

Scuderi and coworkers35 use a 10- to 14-cm skin incision and a medial parapatellar arthrotomy that differs from a standard approach in that the quadriceps tendon is incised only 2 to 4 cm above the superior pole of the patella. The subvastus approach that Hofmann36 described has been modified to make it less invasive. A shortened anterior, midline skin incision is made, and a medial parapatellar arthrotomy follows. The attachment of the vastus medialis obliquus (VMO) muscle to the quadriceps tendon and upper patellar pole is left intact. The VMO muscle belly is then retracted so that limited dissection can occur posterior to the muscle belly, anterior to the intermuscular septum. Synovial release of the suprapatellar pouch is required, and the patella is subluxed laterally.35 The standard midvastus approach that Engh and colleagues37 described has been modified to lessen its damage to the VMO. A shortened midline anterior skin incision is utilized. A medial arthrotomy is made and the incision is extended proximally into the full thickness of the vastus medialis, in-line with its muscle fibers for a length or 4 to 5 cm starting at the superior-medial pole of the patella. The patella is then lateralized but not dislocated.35

The technique that deviates to the greatest degree from traditional techniques and has gained the least general acceptance has been described by Tria and Coon38 and is commonly referred to as the “quadriceps-sparing” technique. This technique uses a curved medial incision from the superior pole of the patella to the tibial joint line. An arthrotomy is then made in line with the skin incision. Bony cuts are made using instruments and guides that fixate and cut from the medial side of the knee rather than the standard anterior location. The quadriceps tendon and VMO are theoretically left completely intact.

EVIDENCE

Hip

In 2005, Ogonda and coauthors13 reported on a prospective, randomized, controlled trial of 219 patients with 219 THAs studied over a period of 6 months. Patients were blinded to length of incision, and all surgery was performed by a single surgeon using a posterior approach. Of critical importance, and one of the strengths of this study, was the fact that the treating surgeon had already become adept at MIS techniques by previously performing 300 short-incision THAs. In the standard-incision group, the subcutaneous tissues and fascia lata were divided in line with the skin incision, which was 16 cm long. In the MIS group, only the proximal 1 cm of the fascia lata was incised. The distal fibers of the gluteus maximus were split by blunt dissection, and the short external rotators were detached close to their insertion into the greater trochanter. These authors found no difference in component position and wound complications, and no evidence of lessened inflammation in the MIS group based on C-reactive protein measurements at 48 hours after surgery. Most remarkably, there were no differences in function immediately after surgery or at 6 weeks, based on Harris hip scores, Oxford hip scores, WOMAC Index of Osteoarthritis and SF-12 general health questionnaire. There was also no benefit for the MIS group in terms of length of hospital stay. These authors conclude that MIS incision surgery performed by an experienced surgeon through a posterior approach is safe but of no benefit in the early postoperative phase. They also caution that more investigation is required to determine the appropriateness of this technique for lower volume and less experienced surgeons.13

Chimento and investigators5 conducted a prospective, randomized comparison of a group of 60 patients with THA through a 15-cm incision with a group that had a modified posterolateral approach and an 8-cm incision. Only patients with a body mass index of less than 30 and no previous hip surgery were included. All procedures involved a single surgeon and anesthetist. After surgery, all patients were supervised by a single physiotherapist. The MIS group was found to have significantly less intraoperative and total blood loss. At 6 weeks after surgery, significantly fewer MIS patients had a residual limp (21.4% vs. 46.8%). No differences were found in any other parameter including length of hospital stay, number of units transfused, postoperative interleukin-6 levels, volume of narcotic used, or utilization of a cane at 6 weeks. There were also no differences between the groups in terms of the position of components or incidence of complications. This well-designed study did indicate that the MIS group may benefit in terms of reduced blood loss; however, the lack of any difference in transfused units and the possibility that there was inadequate numbers to detect differences in complication rates results in no definitive evidence in favor of the MIS approach.

Lawlor and researchers39 have conducted a prospective study of 219 THA replacements that were randomized into either an MIS group (<10 cm) or standard incision (16 cm), performed by a single surgeon with a standardized analgesia and physiotherapy regimen. No significant improvement was noted in the MIS group in terms of ability to transfer, mobilize weight bearing, or walking velocity at 2 days after surgery. No statistically significant difference was found in the length of hospital stay. No significant differences between groups were found at the 6-week mark after surgery. These authors conclude that the MIS approach offered no benefit over the 16-cm incision. It is clear that a posterior approach was used for all hips in this study; however, there is no indication that deep soft-tissue management differed between the two groups. Therefore, this study cannot have implication beyond the impact of a smaller skin incision.

Another study, conducted by Bennett and coworkers,12 also failed to show any significant benefit of MIS THA techniques. These authors compared objective postoperative gait mechanics data by means of a prospective, blinded cohort study of 25 randomly selected patients evaluated on postoperative days 1, 2, and 42 (6 weeks). Nine patients with MIS and eight with standard incision were available for a full set of gait analyses. The standard group experienced greater improvement in sagittal plane hip joint movement between day 2 and week 6 compared with the MIS group. Measurements also suggested that the standard group achieved more normal hip joint kinematics after surgery than did the MIS group. The MIS group demonstrated no early benefit (at day 2) in any kinematic or temporospatial measures. Even at 6 weeks, the temporospatial variables and kinematic ranges of motion were reduced compared with the traditional group. The lack of any significant difference in velocity, step length of the affected or unaffected leg, or stride length or stance phase duration between groups failed to lend support to the MIS technique.

Hart and coworkers6 conducted a prospective study comparing 60 patients randomly selected to have a posterior approach THA with an incision 10 cm or less to a second group of 60 with a standard posterolateral approach. Mean follow-up period was 39 months, and no patients were lost to follow-up. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups including pain, motion, and function. There were also no differences in component positioning or complication rates. These authors caution that the MIS approach has a greater requirement for assistants and should not be attempted in patients with protrusio deformity, fibrous or osseus ankylosis, hips scarred by previous surgery, or obese patients.

The two-incision approach to THA has been among the most controversial of MIS techniques. The developers of this operation have published several technical and experiential reports that were largely favorable and described rapid recovery of function.1,2, 7 However, several studies by other authors have since revealed a difficult learning curve and a complication rate that is of significant concern. Archibeck and White19 examined data provided by the implant manufacturer that played a role in the development of this procedure, which was collected to track the early experiences of surgeons trained in the technique. These authors discovered that the learning curve was likely longer than initially expected based on the 851 cases they reviewed. The rates of femoral fractures (6.5%) and nerve injuries (3.2%) were also found to be much greater than traditional THA. Bal and coauthors20 have also raised concern as they compared the results of the two-incision technique as described by initial innovators1,2, 7 with an MIS approach, which used a single incision. In the two-incision group, 10% of patients required repeat surgery because of a femoral fracture identified after surgery (two hips), dislocation (one hip), a wound complication (two hips), or subsidence and loosening of the femoral implant (four hips). Twenty-five percent of patients suffered an injury of the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, and one patient (one hip) had a neuropraxia of the femoral nerve. In comparison, of the 96 THAs that had been performed with use of a single MIS direct lateral ex-posure of the hip joint, the overall complication rate was 6% and the reoperation rate was 3%. Although the rate of complications with the two-incision technique decreased significantly as the surgeon gained experience, this study raises concern about highly consequential complications early in the learning curve, particularly because these authors are experienced hip surgeons who took the necessary training before initiating the two-incision technique.

Further evidence questioning the value and utility of the two-incision technique was reported by Mardones and coworkers.40 These authors elegantly quantified the extent and location of damage to the abductor and external rotator muscles and tendons after 10 two-incision and 10 miniposterior THAs were conducted on contralateral sides of 10 fresh-frozen cadavers. A surgeon experienced with such procedures performed each approach. A third surgeon assessed the degree of muscle damage using a standardized, published technique,41 and found damage to gluteus medius and gluteus minimus from the two-incision technique was greater than the miniposterior approach. Every two-incision procedure had damage to abductors, external rotators, or both. The mean amount of damage to the gluteus medius muscle for the two-incision technique was 15.14% of its muscular area, whereas the miniposterior technique had a mean of only 4.73%. The damage to the gluteus minimus muscle was similarly greater in the two-incision technique as compared with the miniposterior group. Six of 10 two-incision THAs had complete detachment of the external rotators. Although this was a cadaveric study, and therefore not precisely comparable with living patients, the indications for the two-incision procedure were further eroded because there was absolutely no evidence of lessened muscle or tendon damage. In fact, the extent of abductor damage was actually greater in the two-incision group than in the matched miniposterior group.

Knee

Although a review of the literature reveals fewer data of high quality in the area of MIS TKA than that of THA, adequate information is available to draw some conclusions. Haas and colleagues42 compared 40 consecutive MIS midvastus TKAs without patellar eversion with an age- and sex-matched cohort of TKAs done with a standard technique. Patients achieved motion faster in the MIS group. Mean flexion for minimally invasive total knee replacement at 6 and 12 weeks was 114 (range, 90–132) and 122 (range, 103–135) degrees, respectively, compared with 95 (range, 65–125) and 110 (range, 80–125) degrees for the standard group. The average range of motion at 1 year after surgery in the MIS group was 125 (range, 110–135) degrees compared with 116 (range, 95–130) degrees in the standard group. Postoperative Knee Society scores were greater in the MIS group, and there was no difference in radiographic alignment, infections, extensor mechanism complications, or neurovascular injury. The authors conclude that mini-midvastus approach without patella eversion combined with a small incision was associated with a more rapid functional recovery and improved range of motion without compromise of implant position.42 Laskin and colleagues’43 retrospective mini-midvastus study has also shown improved early range of motion and greater Knee Society functional outcome scores without compromise in radiographic alignment.

In a prospective, observer-blinded study, Boerger and researchers44 studied 120 consecutive patients with TKAs performed by a single surgeon using either the MIS subvastus approach without patella eversion or the standard parapatellar approach with patella eversion. Patients were matched by age, sex, body mass index, knee flexion, deformity, and preexisting high tibial osteotomy. The authors found that the MIS approach was technically more demanding, and inferior visibility prolonged the tourniquet time by an average of 15 minutes. They attributed two intraoperative complications to the poorer exposure. Patients in the MIS subvastus group lost, on average, 100 mL less blood and had better pain scores on day 1 (mean visual analogue scale score: 2.4 vs. 3.89). The MIS group reached 90 degrees of knee flexion earlier (2.8 vs. 4.5 days), and an active straight-leg raise earlier (3.2 vs. 4.1 days). Although the MIS group average flexion at 30, 60, and 90 days was statistically better (100 vs. 94, 110 vs. 106, and 112 vs. 109 degrees), the benefits diminished with time, and the authors doubted the clinical relevance. All patients including those with complications had good results with good component and leg alignment. The authors conclude that the MIS subvastus approach offers early but short-lived benefits for patients at the expense of a longer operation and a greater risk for complications.

A prospective, randomized, double-blind study was conducted by Aglietti and researchers45 to compare the postoperative recovery and early results “quadriceps-sparing” technique with the MIS sub-vastus approach.45 Thirty patients in each group received the same anesthesia protocol and had surgery performed by the same surgeon using the same TKA implants. Evaluation was performed before surgery, in the first week after surgery, and at 1 and 3 months. The authors questioned the feasibility of the quadriceps-sparing technique because these highly experienced knee surgeons required extension of the incision in five cases in the “quadriceps-sparing” group for exposure. Active straight leg raising was achieved half a day earlier, on average, in the MIS subvastus group (1.9 vs. 1.4 days). No further difference was found between the two approaches in relation to short-term recovery or early results; thus, the utility of the technically more challenging quadriceps-sparing technique was questioned. Further evidence by Pagnano and researchers49 used a cadaveric study that reported that any medial arthrotomy that extends more proximal than the midpole of the patella detaches a portion of the quadriceps tendon; thus, the term quadriceps-sparing TKA may be inaccurate.

Nuelle and Mann46 examined 2 groups of 25 patients in a single surgeon’s practice who underwent THA and TKA with standard incisions. The only difference between groups was the anesthesia, pain management, and physical therapy protocols. One group received the protocols described for MIS surgery, whereas the second group had protocols for standard procedures. The surgical technique itself was identical between the two groups. A dramatic reduction in the time it took to achieve the goals for discharge was observed in the MIS protocol group. The MIS protocol group benefited in terms of time to straight leg raise, time to walk 100 m, time to get in and out of bed without assistance, and length of stay. Most patients with the MIS protocols were ready for discharge within 24 hours. The implications of these results are that the benefits of MIS surgery may be unrelated to the surgical procedure itself but rather directly a result of perioperative protocols. If true, this would make the reduction in exposure and the potential inherent risks of MIS surgery of no particular value.

Dalury and Dennis47 have raised concerns about component malposition and potential long-term compromise when MIS TKA techniques are used. In this retrospective, comparative study, the authors compared a group of 30 patients who had MIS TKA with a similar group of 30 patients who had a standardincision TKA. Exposure in both groups was primarily through a midvastus approach, although a medial parapatellar was used in 7 of 30 of the MIS and 9 of 30 standard patients. The MIS group had some minor early advantages in terms of pain medication use and earlier improvement in range of motion; however, by 3 months, the groups were equivalent. Radiographic evaluation revealed that 4 of 30 patients with MIS exposures had tibial component varus (<87 degrees) and none of the standard group had such malalignment.

GUIDELINES

In 2004, the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons (AAHKS) published an advisory statement on the topic of MIS.48 At the time of this statement’s publication, the AAHKS was of the opinion that the potential of MIS surgery for better long-term results, with shorter and less painful recovery, had yet to be scientifically proven. The AAHKS states that is the responsibility of the surgeon to be competent at these techniques and obtain informed consent before performing them.49

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS; www.aaos.org/home.asp) similarly recognizes the importance of studying and validating these procedures but considers MIS surgery to be an “evolving” technique.

CONCLUSIONS

In distinct contrast, however, techniques such as “two-incision” approach to THA and the “quadriceps-sparing” TKA have both failed to demonstrate any advantages in outcomes whereas significant evidence of complications has been documented. Furthermore, there has been convincing cadaveric anatomic data that both of these procedures are not as “muscle sparing” as had been initially believed.40,46 These procedures cannot, therefore, be recommended.

1 Berger R. Mini-incision total hip replacement using an anterolateral approach: Technique and results. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:143-145.

2 Berger RA, Jacobs JJ, Meneghini RM, et al. Rapid rehabilitation and recovery with minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 429; 2004; 239-247.

3 Chung WK, Liu D, Foo LS. Mini-incision total hip replacement—surgical technique and early results. J Orthop Surg. 2004;12:19-24.

4 Wenz JF, Gurkan I, Jibodh SR. Mini-incision total hip arthroplasty: A comparative assessment of perioperative outcomes. Orthopedics. 2002;25:1031-1043.

5 Mow CS, Woolson ST, Ngarmukos SG, Park EH, Lorenz HP. Comparison of scars from total hip replacements done with a standard or a mini-incision. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 441; 2005; 80-85.

6 Hart R, Stipak V, Janecek M, et al. Component position following total hip arthroplasty through miniinvasive posterolateral approach. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;71:60-64.

7 Duwelius PJ, Burkhart RL, Hayhurst JO, et al. Comparison of the 2-incision and mini incision posterior total hip arthroplasty technique: A retrospective match-pair controlled study. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:48-56.

8 Floren M, Lester DK. Durability of implant fixation after less-invasive total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:783-790.

9 O’Brien DA, Rorabeck CH. The mini-incision direct lateral approach in primary total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;441:99-103.

10 Wright JM, Crockett HC, Delgado S, et al. Mini-incision for total hip arthroplasty: A prospective, controlled investigation with 5-year follow-up evaluation. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:538-545.

11 DiGioia AM3rd, Blendea S, Jaramaz B. Computer-assisted orthopaedic surgery: Minimally invasive hip and knee reconstruction. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:183-189.

12 Bennett D, Ogonda L, Elliott D, et al. Comparison of gait kinematics in patients receiving minimally invasive and traditional hip replacement surgery: A prospective blinded study. Gait Posture. 2006;23:374-382.

13 Ogonda L, Wilson R, Archbold P, et al. A minimal-incision technique in total hip arthroplasty does not improve early postoperative outcomes. A prospective, randomized, controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:701-710.

14 Ciminiello M, Parvizi J, Sharkey PF, et al. Total hip arthroplasty: Is small incision better? J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:484-488.

15 de Beer J, Petruccelli D, Zalzal P, et al. Single-incision, minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: Length doesn’t matter. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:945-950.

16 Rosenberg AG. A two-incision approach: Promises and pitfalls. Orthopedics. 2005;28:935-936.

17 Weng HH, Fitzgerald J. Current issues in joint replacement surgery. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006;18:163-169.

18 Woolson ST, Mow CS, Syquia JF, et al. Comparison of primary total hip replacements performed with a standard incision or a mini-incision. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1353-1358.

19 Archibeck MJ, White REJr. Learning curve for the two-incision total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 429; 2004; 232-238.

20 Bal BS, Haltom D, Aleto T, et al. Early complications of primary total hip replacement performed with a two-incision minimally invasive technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:2432-2438.

21 Bottner F, Delgado S, Sculco TP. Minimally invasive total hip replacement: The posterolateral approach. Am J Orthop. 2006;35:218-224.

22 Howell JR, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Minimally invasive versus standard incision anterolateral hip replacement: A comparative study. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:153-156.

23 Parvizi J, Sharkey PF, Pour AE, et al. Hip arthroplasty with minimally invasive surgery: A survey comparing the opinion of highly qualified experts vs patients. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6 suppl 2):38-46.

24 Teet JS, Skinner HB, Khoury L. The effect of the “mini” incision in total hip arthroplasty on component position. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:503-507.

25 Berry DJ, Berger RA, Callaghan JJ, et al. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Development, early results, and a critical analysis. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Orthopaedic Association, Charleston, South Carolina, USA, June 14, 2003. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:2235-2246.

26 Hungerford DS. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: In opposition. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19(4 suppl 1):81-82.

27 Woolson ST. In the absence of evidence—why bother? A literature review of minimally invasive total hip replacement surgery. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:189-193.

28 Holt G, Wheelan K, Gregori A. The ethical implications of recent innovations in knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88-A:226-229.

29 Ranawat CS, Ranawat AS. A common sense approach to minimally invasive total hip replacement. Orthopedics. 2005;28:937-938.

30 American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Advisory Statement. Minimally Invasive and Small Incision Joint Replacement Surgery: What Surgeons Should Consider. American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons online. http://www.aahks.org/pdf/MIS_position_statement.pdf. Accessed August 2007.

31 Chimento GF, Pavone V, Sharrock N. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: A prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:139-144.

32 Toms A, Duncan CP. The limited incision, anterolateral, intermuscular technique for total hip arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:199-203.

33 Berger RA. The technique of minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty using the two-incision approach. Instr Course Lect. 2004;53:149-155.

34 Bonutti PM, Mont MA. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A(suppl 2):26-32.

35 Scuderi GR, Tenholder M, Capeci C. Surgical approaches in mini-incision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 428; 2004; 61-67.

36 Hofmann AA, Plaster RL, Murdock LE. Subvastus (Southern) approach for primary total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 269; 1991; 70-77.

37 Engh GA, Holt BT, Parks NL. A midvastus muscle-splitting approach for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:322-331.

38 Tria AJJr, Coon TM. Minimal incision total knee arthroplasty: Early experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 416; 2003; 185-190.

39 Lawlor M, Humphreys P, Morrow E, et al. Comparison of early postoperative functional levels following total hip replacement using minimally invasive versus standard incisions. A prospective randomized blinded trial. Clin Rehabil. 2005;19:465-474.

40 Mardones R, Pagnano MW, Nemanich JP. The Frank Stinchfield Award: Muscle damage after total hip arthroplasty done with the two-incision and mini-posterior techniques. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 441; 2005; 63-67.

41 McConnell T, Tornetta P3rd, Benson E. Gluteus medius tendon injury during reaming for gamma nail insertion. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 407; 2003; 199-202.

42 Haas SB, Cook S, Beksac B. Minimally invasive total knee replacement through a mini midvastus approach: A comparative study. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 428; 2004; 68-73.

43 Laskin RS, Beksac B, Phongjunakorn A. Minimally invasive total knee replacement through a mini-midvastus incision: An outcome study. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 428; 2004; 74-81.

44 Boerger TO, Aglietti P, Mondanelli N. Mini-subvastus versus medial parapatellar approach in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 440; 2005; 82-87.

45 Aglietti P, Baldini A, Sensi L. Quadriceps-sparing versus mini-subvastus approach in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 452; 2006; 106-111.

46 Nuelle DG, Mann K. Minimal incision protocols for anesthesia, pain management, and physical therapy with standard incisions in hip and knee arthroplasties: The effect on early outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:20-25.

47 Dalury DF, Dennis DA. Mini-incision total knee arthroplasty can increase risk of component malalignment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;440:77-81.

48 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Advisory Statement: Minimally Invasive and Small Incision Joint Replacement Surgery. Available at: http://www.aaos.org/home.asp. Accessed August 2007.

49 Pagnano MW, Meneghini RM, Trousdale RT. Anatomy of the extensor mechanism in reference to quadriceps-sparing TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 452; 2006; 102-105.

50 Kolisek FR, Bonutti FM, Hozack WJ, et al. Clinical experience using a minimally invasive surgical approach for total knee arthroplasty: early results of a prospective randomized study compared to a standard approach. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:8-13.