Chapter 21 What Are the Best Diagnostic Criteria for Lateral Epicondylitis?

Lateral epicondylitis is a common entity that affects up to 1% to 3% of the population. Historically, it has been termed writer’s cramp,1 rider’s sprain,2 and finally, the more familiar tennis elbow3; but in fact, only 5% to 10% of affected individuals actually play tennis. It is more frequent in sports and occupations that require repetitive actions of the hand and wrist, and can account for up to 50% of elbow injuries in athletes using overhead arm motions in their sport. The incidence is approximately 4 to 7 cases per 1000 patients, with a peak occurrence in patients aged 35 to 54 years. Similar symptoms can occur on the medial side of the elbow, but lateral elbow pain is more predominant with a 4:1 to 7:1 ratio. Symptoms last, on average, from 6 months to 2 years, with 89% of patients recovering within 1 year. Risk factors include overuse, repetitive movements, training errors, misalignments, flexibility problems, aging, poor circulation, strength deficits or muscle imbalance, and psychological factors.4,5 More than 40 treatment options are described, with little scientific rationale for most of them.6–8 Systematic literature reviews have identified substantive problems including the lack of proper randomized, controlled clinical trials, poor-quality studies, and vague inclusion criteria. No doubt contributing to the problem is the lack of evidence-based diagnostic criteria and outcome measures.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

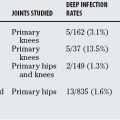

Cyriax9 in 1936 recognized that the origin of extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB) was the primary site of injury. Other muscles involved are the extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor carpi ulnaris extensor digitorum communis (in at least 50% of cases) and the supinator muscle (Fig. 21-1). The condition also requires detailed evaluation and consideration to exclude neuropathy, such as radial tunnel syndrome, posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) compression, or both.10 The radial nerve can be entrapped at several sites (Fig. 21-2): by fibrous bands in front of the radial head, by the recurrent radial vessels (leash of Henry), at the arcade of Frohse (proximal thickened edge of superficial head of supinator muscle), and at the tendinous margin of the ECRB.

FIGURE 21-1 Anatomy of the lateral elbow.

(Adapted with permission from Bishai SK, Plancher KD: The basic science of lateral epicondylosis: Update for the future. Tech Orthop 21:250–255, 2006.)

In chronic cases of lateral epicondylitis, it has been shown that there are little to no inflammatory cells, hence the term tendonitis is inappropriate because -itis implies inflammation. Nirschl11 rather described it as “tendinosis” or “angiofibroblastic hyperplasia,” reflecting the degenerative changes based on histopathologic diagnosis. A review of histologic, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopy suggests that the condition is degenerative12,13 with increased fibroblasts, vascular hyperplasia, proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans, and disorganized and immature collagen. This is in keeping with current thinking about tendon pathology in general.14,15

Many names have been proposed for this condition—tennis elbow, radial or lateral epicondylalagia,16 extensor tendinopathy, or epicondylitis lateralis humeri. The primary argument against lateral epicondylalgia (algia means “pain”) is that lateral elbow pain can also result from PIN entrapment (radial tunnel syndrome) and from compression of the nerves of the cervical spine; therefore, this is probably too general a term for diagnosis. The term extensor tendinopathy is not inclusive enough because often more than the wrist extensor tendons are involved (ECRB and sometimes the supinator muscle). Some authors17 have suggested that it is most appropriately termed lateral elbow tendinopathy, a painful overuse tendon condition in the area of lateral epicondyle. For purposes of consistency in the remainder of this review, however, the term lateral epicondylitis is used.

CLINICAL DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Lateral epicondylitis is characterized by a corroborating history of injury and is a localized tenderness in the area where the common wrist extensors (especially ECRB) attach to the lateral epicondyle of the humerus.18 Functional use, such as gripping or lifting heavy objects, exacerbates symptoms. Differential diagnoses include radial nerve entrapment (or rarely, lateral antebrachial cutaneous neuropathy), elbow joint disease (osteochondral desiccans, intra-articular loose bodies, osteoarthrosis), partial or complete tear of the tendon, and extrinsic causes (cervical dysfunction and nerve root compression).19 Infrequently seen are degeneration or stenosis of the orbicular ligament, chronic impingement of the redundant synovial fold between the humerus and radial head, traumatic periostitis of the lateral epicondyle, and chondromalacia of the radial head and capitellum.

Clinical examination should include visual inspection of the elbow for alignment (varus or valgus angulation), muscle bulk, and obvious bruising or swelling; however, none of these is diagnostic. Elbow range of motion is sometimes decreased; one study found a decrease of 10% in supination and 15% in pronation in 25 patients with chronic unilateral epicondylosis.20 Previous cortisone injections may leave residual skin discoloration or lack of pigmentation. Neurovascular examination of the distal extremity is also necessary.

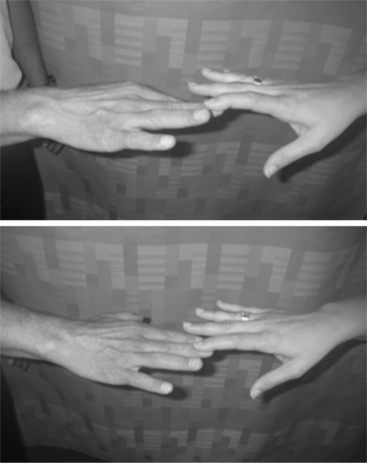

The diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis is substantiated by tenderness over the ECRB or common extensor origin. The therapist or physician should be able to reproduce the typical pain by the following methods: (1) digital palpation on the facet of the lateral epicondyle, (2) resisted wrist extension (Fig. 21-3) or resisted middle-finger extension with the elbow in extension (Fig. 21-4), or (3) having the patient grip an object. In addition to pain, patients almost always have decreased function. In radial tunnel syndrome21 (which may coexist with lateral epicondylitis in up to 5% of cases), the pain is more diffuse and localized to the extensor mass, 3 to 4 cm distal to the lateral epicondyle. It may be provoked with supinator stress testing or resisted extension of the middle finger. Weakness of the distal muscle groups innervated by the PIN may also be present.

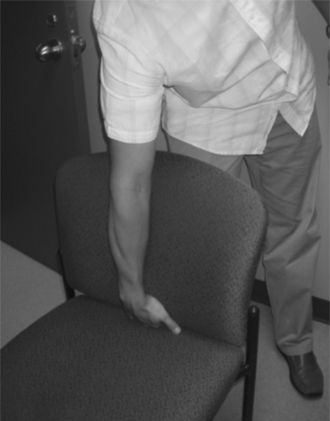

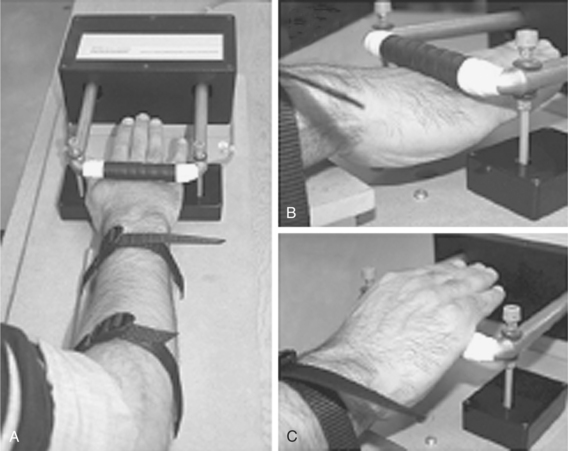

Other tests have been described,22,23 including Cozen’s test (with the elbow flexed and the forearm pronated, the patient is asked to make a fist and radially deviate and extend the wrist against resistance) (Fig. 21-5). Mill’s test (Fig. 21-6) refers to pain (on resisted wrist extension) with the elbow extended and wrist flexed and pronated with radial deviation.24 Coonrad and Hooper24 have also described the “coffee cup test,” where picking up a cup of coffee is painful. Another useful clinical tool is the “chair test” (Fig. 21-7), where the patient is asked to pick up a chair with the elbow extended and the wrist ulnarly deviated with the hand in palmar flexion.25 One group studied a standardized and calibrated system to simulate the chair pick-up.26 They demonstrated excellent reliability (inter-rater intraclass correlation coefficients [ICCs] ranging from 0.80–0.93 and intrarater ICCs ranging from 0.9–0.97) and reproducibility of results. Measurements in a group of 16 patients with MRI-confirmed diagnosis suggested that this test could be valid for monitoring patients with lateral epicondylosis. Other researchers27 used an extensor grip test (where pain on resisted wrist extension was diminished by the examiner gripping the patients arm just below the elbow with an estimated 10–N pressure) to prospectively predict which patients would respond best to bracing. The validity (specifically the sensitivity and specificity) of the majority of these clinical tests has not yet been determined. This area is ripe for research, with a significant need for well-designed studies,28 such as recently published for diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome.29 Tests can also be validated against tissue observations of pathology or imaging studies.

OUTCOME MEASURES

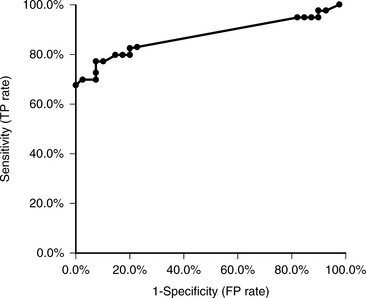

A variety of specific outcome measures has been used to assess the effects of therapy. None is specifically diagnostic, and they are mainly used to quantify the severity of elbow injury and to monitor effectiveness of rehabilitation protocols. In some cases, they can help distinguish a patient population with the disease from healthy control subjects. Measures of pain include pain threshold test (dolorimeter), size of pain drawing, and visual analogue scales (VASs), but only pressure pain is associated with pain on palpation, grip strength, and manual tests.30 Both maximal grip strength and pain free grip strength have been utilized,31 and the latter has been shown to be moderately reliable.32,33 Assessment of mean and maximal grip strength is done with an instrument such as a Jamar hydraulic hand dynamometer, with the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion and the elbow fully extended in front of patient. An average of multiple measurements is recommended, and from multiple sessions rather than from increasing the repetitions in a single test session. Dorf and colleagues34 examined the sensitivity and specificity of grip strength in these positions in a population of 81 patients with lateral epicondylitis. In 41 patients, the affected side only was tested, whereas 40 had bilateral measurements done. The affected extremity was 29% stronger in flexion than in extension. The authors suggest that loss of grip strength between flexion and extension in a single extremity should be considered as a test to distinguish an extremity with lateral epicondylitis from a pain-free extremity. With a 5% decrease in grip strength between flexion and extension, the sensitivity was 83% and specificity 80%; with a 10% decrease, sensitivity was 78% and specificity 90% (Fig. 21-8). DeSmet and colleagues35,36 had similar findings: a statistically significant mean grip strength loss of 43% from flexion to extension for the pathologic side in 55 consecutive patients with lateral epicondylitis compared with a less than 2% difference for the control side. In their studies, grip strength in both elbow extension and flexion significantly improved after surgery and correlated with a good clinical outcome.

Forearm muscle imbalance or shoulder muscle pathology may also be important in the development of tennis elbow. It has been suggested that there is a greater fatigability of wrist extensors compared with wrist flexors.37 Alizadehkhaiyat and coworkers38 actually developed an extension/flexion dynamometer type instrument to measure this (Fig. 21-9), but no other systematic studies have been done on this wrist-forearm-shoulder segment. Isokinetic dynamometer measurements have shown peak torque at a radial velocity of 90 degrees/sec, and work in wrist flexion reduced by 17% in lateral epicondylitis and 13% in medial epicondylitis.

FIGURE 21-9 Wrist-hand dynamometer.

(Reprinted from Alizadehkhaiyat O, Fisher AC, Kemp GJ, Frostick SP: Strength and fatiguability of selected muscles in upper limb: Assessing muscle imbalance relevant to tennis elbow. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 17:428–436, 2007, with permission of Elsevier.)

Another study looked at strength with a device called the Marcy Wedge-Pro (MWP), commonly used by tennis players for training,39 to quantitatively assess ability to perform wrist extension exercises. The MWP results were compared with clinical measures and found to accurately identify patients who responded to treatment (P, 0.05). Another group40 explored the clinical utility of a middle digit isokinetic eccentric strength dynamometer for evaluating the effects of lateral epicondylitis therapy. Eccentric isokinetic tor-que, work power, and angle at peak torque of the third finger were tested in 2 groups of patients: one without physician-diagnosed lateral epicondylitis (13 male and 14 female patients) and the other with lateral epicondylitis (13 male and 14 female patients). Test-retest correlation values ranged from 0.83 to 0.45, and analysis of variance showed a significant difference in all variables between the two subject groups.

ELECTROMYOGRAPHY

Electromyography is used mainly for diagnosis of radial tunnel syndrome, but it is not often positive. Roles and Maudsley10 note a delay in motor conduction velocity in “some cases,” but normal electrophysiologic findings do not exclude the entrapment diagnosis. Bauer and Murray41 used surface electromyography and demonstrated significantly earlier, longer, and greater activation of the wrist extensor muscles in a group suffering from lateral tennis elbow versus healthy control subjects. This type of work may lead to some insight into the pathogenesis of this chronic condition and suggest therapies.

PATIENT-RATED QUESTIONNAIRES

Traditional pain and disability questionnaires, such as the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire, and VAS are used in outcome studies, but they are nonspecific. A Patient-Rated Forearm Evaluation Questionnaire has been developed, using 5 items to assess pain and 10 items to assess function during the previous week.42 This has been shown to have high reliability, but only fair correlation with pain-free grip strength. Further refinements have confirmed the reliability and reproducibility, and have validated that it is at least as sensitive to change as other commonly used outcome scales.43 It has subsequently been renamed the Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation (PRTEE).44 Recently, it has been utilized concurrently with an outcome therapy study in 78 patients who play tennis and have MRI-confirmed lateral elbow tendinopathy.45 Detailed and favorable assessment of internal consistency, construct validity, reproducibility, and sensitivity to change led these authors to suggest that the PRTEE should become the standard primary outcome measure in research on tennis elbow.

PLAIN RADIOGRAPHS

Although sometimes useful to exclude other pathology, plain radiographs are not diagnostic for this condition, and thus are not necessary as an initial step in evaluation. In a consecutive series of 294 radiographs (standard anteroposterior, lateral, and radiocapitellar views in patients with lateral epicondylitis), 16% had findings present, most commonly faint calcification along the lateral epicondyle in 20 patients (7%) (Fig. 21-10). However, management was altered by only 2 of the sets of films.46

DIAGNOSTIC ULTRASOUND

Diagnostic ultrasound is a noninvasive imaging modality that uses sound waves in the frequency range of more than 20,000 Hz. Better resolutions are att-ained with higher frequencies of scanning, but at the expense of less depth of field. This technique is best for assessment of tendon integrity. Additional passive or resisted dynamic imaging can further evaluate function and continuity of the tendon, as well as visualize any gaps.47 Disadvantages of diagnostic ultrasound include the fact that it is very much operator dependent, and it is also limited by the resolution of the equipment. Printed images are only a snapshot of the dynamic process of evaluation, and thus cannot be used in isolation.48

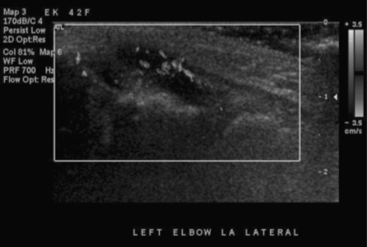

On ultrasound, tendon degeneration is visualized as irregularities of fibrillar appearance, with thickening, focal hypoechoic areas, calcification, and sometimes cortical irregularity or spur formation of the epicondyle (Fig. 21-11). In tendons with a synovial sheath, widening of the sheath can be seen, as well as increased fluid within it. Tendon ruptures appear as fragmented contiguous fibrils. It has been suggested that intrinsic changes in the tendon can be detected earlier with ultrasound than with MRI. Calcification is also noted earlier with ultrasound than with MRI. The addition of color Doppler permits visualization of neovascularization (Fig. 21-12), which is thought to be a source of the pain in such tendinopathies (growth factors, pain fibers, etc.). It also provides a method by which these pathologic neovessels can be treated with various sclerosing agents such as polidocanal or glycerol.

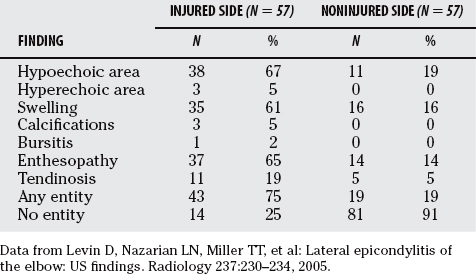

Some studies of clinical correlation have been performed. Maffulli and investigators49 were able to identify six different entities: enthesopathy, tendonitis, peritendinitis, bursitis, intramuscular lesions, and mixed lesions, and suggested a possible prognostic value in patients with tennis elbow. They were able to confirm the clinical diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis by sonographic abnormalities in 93% of their patients. Connell and coworkers50 studied 75 patients, with a 95% confirmation rate (4 tendons were normal). The most common finding was a hypoechoic area in 64% of these images. Another group,51 in a well-designed study, documented hyperechogenicity, swelling, calcification, bursitis, enthesopathy, and tendinosis in 75% of patients with an injured extremity. Positive and negative predictive values are shown in Table 21-1 and Table 21-2. However, no significant predictive values of sonographic abnormalities were found for either success rate of treatment or mean decrease in pain.

The most thorough study so far52 retrospectively reviewed images of 20 elbows in 10 asymptomatic volunteers (6 men, 4 women; age range, 22–38 years; mean, 29.6 years) compared with 37 elbows in 22 patients with symptoms of lateral epicondylitis (10 men, 12 women; age range, 30–59 years; mean, 46 years). A total of 57 images were randomly selected and interpreted by 3 individual readers for 1 or more of 8 ultrasound findings. Intrareader variability was assessed at two separate sessions. Sensitivity varied from 72% to 88%, and specificity from 36% to 48.5%. The odds ratio was significant (P <0.05%) for calcification of common extensor tendon, tendon thickening, adjacent bone irregularity, focal hyoechoic regions, and diffuse heterogeneity, but not significant for linear intrasubstance tears and peritendinous fluid.

Using another method called spatial compoundsonography, sonographic information is obtained from several different angles and combined to produce a single image. In one study of 34 patients,53 real-time spatial compound sonography (with a 12-5-MHz multifrequency linear array transducer) significantly improved definition of soft-tissue planes, reduced speckle and other noise, and improved image detail when compared with conventional high-resolution sonography (P <0.0001 for all evaluated parameters). Nevertheless, this technique is not routinely used.

Finally, Miller and coworkers54 used ultrasound to examine 11 patients with tennis elbow and a normal contralateral elbow. In 10 of these patients, as well as in 6 asymptomatic volunteers, they were able to compare MRIs. Sonographic features of epicondylitis included outward bowing of the common tendon, presence of hypoechoic fluid subadjacent to the common tendon, thickening, decreased echogenicity, and ill-defined margins of the common tendon. Sensitivity for detecting epicondylitis ranged from 64% to 82% for sonography and from 90% to 100% for MRI. Specificity ranged from 67% to 100% for sonography and from 83% to 100% for MRI. The authors conclude that sonography is as specific but not as sensitive as MRI for evaluating epicondylitis. Used as an initial imaging tool, sonography may be adequate for diagnosing this condition in many patients, thus allowing MRI to be reserved for patients with symptoms whose sonographic findings are normal.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

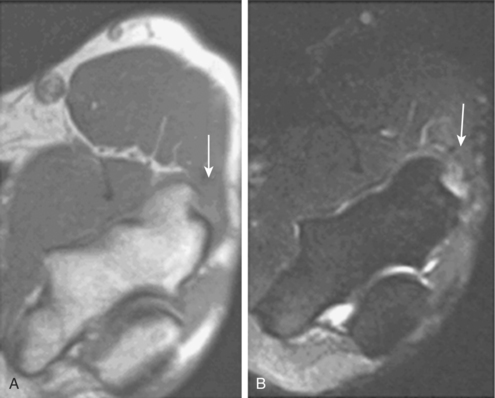

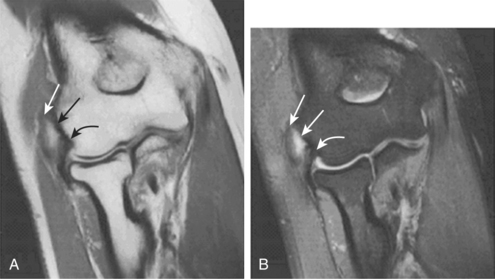

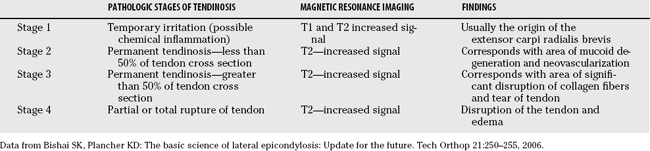

MRI gives excellent detail and soft-tissue contrast. Coronal and axial fast short-T1 inversion recovery and fat-suppressed T2-weighted images are good for interstitial fluid and edema in and around tendon and bone, whereas T1-weighted or proton density–weighted images illustrate anatomic structures and fat planes.55,56 Tendinosis can be seen with or without superimposed partial- or full-thickness tearing, as well as chondromalacia, synovitis, osteophytic spurring, or loose bodies. Pathologic features suggesting lateral epicondylitis include thickening and high-intensity signal in tendon, as well as dystrophic calcification on gradient-echo techniques (Figs. 21-13 through 21-15). Bone marrow edema of the lateral epicondyle, anconeus muscle edema, and fluid within the radial head bursa may also be visualized.57 MRI is also useful in differential diagnosis of the less common radial tunnel syndrome, through demonstration of denervation edema or atrophy within muscles innervated by the PIN, and mass effects along the course of the nerve.58 A reasonable correlation of MRI findings with the stages of tendinosis also exists59 (Table 21-3). Although most imaging is currently performed on high-field whole-body scanners (>1.0 Tesla), there is also increasing interest in low (<0.5 Tesla) and medium (0.5–1.0 Tesla) field strengths, available with smaller, less expensive scanners, which can be installed in physicians’ offices.60 Patients can then be scanned in sitting or recumbent positions, making this test much more practical and accessible.

FIGURE 21-13 Magnetic resonance imaging findings in lateral epicondylitis.

(From Saliman JD, Beaulieu CF, McAdas TR: Ligament and tendon injury to the elbow: Clinical surgical and imaging features. Top Magn Reson Imaging 17:327–336, 2006, 2006, reprinted with permission.)

FIGURE 21-14 Magnetic resonance imaging findings in lateral epicondylitis.

(Reprinted from Banks KP, Ly JZ, Beall DP, et al: Overuse injuries of the upper extremity in the competitive athlete: Magnetic resonance imaging findings associated with repetitive trauma. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 34:127–142, 2005, with permission of Elsevier.)

FIGURE 21-15 Magnetic resonance imaging findings in lateral epicondylitis.

(Reprinted with permission From Fritz RC, Breidahl WH: Radiographic and special studies: Recent advances in imaging of the elbow. Clin Sports Med 23:567–580, 2004.)

TABLE 21-3 Correlation of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings with Pathologic Stages of Lateral Epicondylitis

In conclusion, little to no evidence (grade C) exists to support the validity of the various clinical findings and special examination techniques for the diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis. Some nonspecific strength and pain measures are useful in predicting response to therapy but are less helpful for diagnosis. Fair evidence (grade B recommendation) has been reported for utilization of some specialized outcome scales (such as the PRTEE), especially for longitudinal therapeutic studies. Imaging modalities for this common entity, in particular, diagnostic ultrasound and MRI, continue to become more detailed and refined in confirming the diagnosis, as well as more easily available to the clinician. Despite the fact that they are not the first step in evaluation of this condition, fair evidence (grade B) exists for their diagnostic utility and precision. It would seem important, therefore, to establish a “gold standard” for diagnosis of lateral epicondylitis, comparing anatomic and/or radiologic findings with clinical diagnostic criteria. This will reduce inconsistencies and improve the accuracy of diagnosis, as well as enable larger-scale epidemiologic studies and establishment of evidence-based conservative or surgical treatment guidelines. Table 21-4 provides a summary of recommendations.

| LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | RATIONALE | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical evaluation | C | Little or no evidence exists to support the validity of the various clinical findings and special examination techniques. |

| Outcome measurement | B | Fair evidence has been reported for utilization of some specialized outcome scales (e.g., Patient-Rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation). |

| Imaging modalities | B | Fair evidence exists for the diagnostic utility and precision of diagnostic ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging. |

1 Runge F. Zur genese und behandlung des schreibe kranfes. Bed Kin Worchenschr. 1873;10:245-248.

2 Morris H. The rider’s sprain. Lancet. 1882;2:133-134.

3 Major HP. Lawn tennis elbow. J Br Med. 1883;2:557.

4 Allander E. Prevalence, incidence and remission rates of some common rheumatic diseases and syndromes. Scand J Rheum. 1974;3:145-153.

5 Almekinders LC, Temple JD. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of tendonitis: An analysis of the literature. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:1183-1190.

6 Labelle H, Guibert R, Joncas J, et al. Lack of scientific evidence for the treatment of lateral epicondylitis of the elbow. An attempted meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74:646-651.

7 Hudak P, Cole D, Haines A. Understanding prognosis to improve rehabilitation: The example of lateral elbow pain. Arch Phys Med. 1996;77:586-592.

8 Assendelft W, Green S, Buchbinder R, et al. Tennis elbow (lateral epicondylitis). Clin Evid. 2003;9:1388-1398.

9 Cyriax JH. The pathology and treatment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1936;18:921-938.

10 Roles NC, Maudsley RH. Radial tunnel syndrome: Resistant tennis elbow as nerve entrapment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1972;54:499-508.

11 Nirschl RP. Tennis elbow. Orthop Clin North Am. 1973;4:787-800.

12 Nirschl RP. Elbow tendinosis/tennis elbow. Clin Sports Med. 1992;11:851-870.

13 Kraushaar BS, Nirschl RP. Tendinosis of the elbow (tennis elbow). Clinical features and findings of histological, immunohistochemical and electron microscopy studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:259-278.

14 Khan K, Cook J, Taunton J, et al. Overuse tendinosis, not tendonitis: A new paradigm for a difficult clinical problem. Phys Sport Med. 2000;28:38-48.

15 Khan KM, Cook JL, Kannus P, et al. Time to abandon the “tendinitis” myth. Br Med J. 2002;324:626-627.

16 Waugh E. Lateral epicondylalgia or epicondylitis: What’s in a name? J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 2005;35:200-202.

17 Stansinopoulos D, Johnson MI. ‘Lateral elbow tendinopathy’ is the most appropriate diagnostic term for the condition commonly referred to as lateral epicondylitis. Med Hypotheses. 2006;67:1399-1401.

18 Nirschl R, Ashman E. Elbow tendinopathy: Tennis elbow. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;22:813-836.

19 Hume PA, Reid D, Edwards T. Epicondylar injury in sport: Epidemiology, type, mechanisms, assessment, management and prevention. Sports Med. 2006;36:151-170.

20 Pienimäki TT, Siira PT, Vanharanta H. Chronic medial and lateral epicondylitis: A comparison of pain, disability and function. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:317-321.

21 Lister GD, Belsole RB, Keinert HE. The radial tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg. 1979;4:52-59.

22 Dutton M. Orthopedic Examination, Evaluation and Intervention. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, 2004;543-544.

23 Wadsworth TG. Tennis elbow: Conservative, surgical and manipulative treatment. BMJ. 1987;294:621-624.

24 Coonrad RW, Hooper WR. Tennis elbow: Its course, natural history, conservative and surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg. 1973;55A:1117-1182.

25 Gardner RC. Tennis elbow: Diagnosis, pathology and treatment. Clin Orthop. 1970;72:248-253.

26 Paoloni JA, Appleyard RC, Murrell GAC. The Orthopedic Research Institute-Tennis Elbow Testing System: A modified chair pick-u test—Interrrater and intrarater reliability testing and validity for monitoring lateral epicondylosis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:72-77.

27 Struijs PAA, Assendelft WJJ, Kerkhoffs GMM, et al. The predictive value of the extensor grip test for the effectiveness of bracing for tennis elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1905-1909.

28 Boyer MI, Hastings H. Lateral tennis elbow: “Is there any science out there?”. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:481-491.

29 Graham B, Regehr G, Naglie G, Wrist JG. Development and validation of diagnostic criteria for carpal tunnel syndrome. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2006;31A:9191-9197.

30 Pienimäki T, Tarvainen T, Siira P, et al. Associations between pain, grip strength and manual tests in the treatment evaluation of chronic tennis elbow. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:164-170.

31 Smidt N, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of the assessment of severity of complaints, grip strength, and pressure pain threshold in patients with lateral epicondylitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1145-1150.

32 Stratford PW, Norman GR, McIntosh JM. Generalizability of grip strength measurements in patients with tennis elbow. Phys Ther. 1989;68:276-281.

33 Hamilton A, Balnave R, Adams R. Grip strength testing reliability. J Hand Ther. 1994;7:163-170.

34 Dorf ER, Chhabra AB, Golish SR, et al. Effect of elbow position on grip strength in the evaluation of lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2007;32A:882-886.

35 DeSmet L, Fabry G. Grip strength in patients with tennis elbow. Influence of elbow position. Acta Orthop Belg. 1996;62:26-29.

36 DeSmet L, Van Ransbeeck H, Fabry G. Grip strength in tennis elbow: Long-term results of operative treatment. Acta Orthop Belg. 1998;64:167-169.

37 Hagg GM, Milerad E. Forearm extensor and flexor muscle exertion during simulated gripping work—an electromyographic study. Clin Biomech. 1997;12:39-43.

38 Alizadehkhaiyat O, Fisher AC, Kemp GJ, Frostick SP. Strength and fatiguability of selected muscles in upper limb: Assessing muscle imbalance relevant to tennis elbow. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2007;17:428-436.

39 Smith RW, Mani R, Cawley MID, et al. Assessment of tennis elbow using the Marcy Wedge-Pro. Br J Sports Med. 1993;27:233-236.

40 Pearson D, Gehlsen GM, Wilson JK, et al. An objective measure of lateral epicondylitis. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 1998;7:27-31.

41 Bauer JA, Murray RD. Electromyographic patterns of individuals suffering from lateral tennis elbow. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 1999;9:245-252.

42 Overend TJ, Wuori-Fearn JL, Kramer JF, MacDermid JC. Reliability of a patient-rated forearm evaluation questionnaire for patients with lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Ther. 1999;12:31-37.

43 Newcomer KL, Martinez-Silvestrini JA, Schaefer MR, et al. Sensitivity of the Patient-rated Forearm Evaluation Questionnaire in lateral epicondylitis. J Hand Ther. 2005;18:400-406.

44 MacDermid J. Update: The Patient-rated Forearm Evaluation Questionnaire is now the Patient-rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation. J Hand Ther. 2005;18:407-410.

45 Rompe JD, Overend TJ, MacDermid JC. Validation of the Patient-rated Tennis Elbow Evaluation Questionnaire. J Hand Ther. 2007;20:3-11.

46 Pomerance J. Radiographic analysis of lateral epicondylitis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:156-157.

47 Lew HL, Chen CPC, Wang T-G, Chew KTL. Introduction to musculoskeletal diagnostic ultrasound: Examination of the upper limbs. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:310-321.

48 Allen GM, Wilson DJ. Ultrasound in sports medicine—a critical evaluation. Eur J Radiol. 2007;62:79-85.

49 Maffulli N, Regine R, Carrillo F, et al. Tennis elbow: An ultrasonographic study in tennis players. Br J Sports Med. 1990;24:151-155.

50 Connell D, Burke P, Coombes P, et al. Sonographic examination of lateral epicondylitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:777-782.

51 Struijs PAAA, Spruyt M, Assendelft WJJ, van Dijk CN. The predictive value of diagnostic sonography for the effectiveness of conservative treatment of tennis elbow. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:1113-1118.

52 Levin D, Nazarian LN, Miller TT, et al. Lateral epicondylitis of the elbow: US findings. Radiology. 2005;237:230-234.

53 Lin DC, Nazarian LN, O’Kane PL, et al. Advantages of real-time spatial compound sonography of the musculoskeletal system versus conventional sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1629-1631.

54 Miller TT, Shapiro MA, Schultz E, Kalish PE. Comparison of sonography and MRI for diagnosing epicondylitis. J Clin Ultrasound. 2002;30:193-202.

55 Saliman JD, Beaulieu CF, McAdas TR. Ligament and tendon injury to the elbow: Clinical surgical and imaging features. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;17:327-336.

56 Kijowski R, Tuite M, Sanford M. Magnetic resonance imaging of the elbow. Part II: Abnormalities of the ligaments, tendons, and nerves. Skelet Radiol. 2004;34:1-18.

57 Tuitje MJ, Kijowski R. Sport-related injuries of the elbow: An approach to MRI interpretation. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25:387-408.

58 Ferdinand BD, Rosenberg ZS, Schweitzer ME. MR imaging features of radial tunnel syndrome: Initial experience. Radiology. 2006;240:161-168.

59 Nirschl RP, Pettrone FA. Tennis elbow. The surgical treatment of lateral epicondylitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1979;61:832-839.

60 Ghazinoor S, Crues JVIII. Low field MRI: A review of the literature and our experience in upper extremity imaging. Clin Sports Med. 2005;25:591-606.