Chapter 95 What Are Effective Therapies for Anterior Knee Pain?

Anterior knee pain or patellofemoral (PF) pain is one of the commonest conditions presenting to clinicians involved in the management of sports injuries.1,2 Prospective cohort studies report incidence rates of 7% to 15% in sporting and general populations.3–6

SOURCES OF PAIN

Much speculation had been made about the source of PFP, but evidence is mounting that the richly innervated infrapatellar fat pad could be a significant player.7,8 A recent study by Bennell and colleagues,9 in which the fat pad of asymptomatic individuals was injected with hypotonic saline, confirmed the finding that the fat pad can be a potent source of knee pain symptoms that are not just confined to the infrapatellar region but can refer to the proximal thigh as far as the groin. In addition, the lateral retinaculum seems to be responsible for some PF symptoms because numerous studies demonstrate nerve damage in the lateral retinaculum of patients with PFP, including nerve fibrosis, neuroma formation, and increased number of myelinated and unmyelinated nerve fibers with a predominant nociceptive component.10–12

Factors Predisposing to Patellofemoral Pain

Several factors predisposing an individual to PFP have been identified, ranging from overuse and training errors to faulty biomechanics. Structural causes of PFP are divided into intrinsic and extrinsic causes. Intrinsic structural factors are uncommon and relate to dysplasia of the patella or femoral trochlea and the position of the patella relative to the trochlea. Extrinsic structural faults are reported to cause a lateral tracking of the patella.1,13, 14 The extrinsic factors include increased Q angle, hamstrings and gastrocnemius muscle tightness, abnormal foot pronation, and quadriceps muscle dysplasia.

The Q angle, representing the line of pull of the rectus femoris muscle, has long been the benchmark of orthopedic surgeons to indicate PF function. Its value is widely debated in the literature, with many authors questioning the diagnostic relevance of the static Q angle, suggesting the dynamic Q angle has greater relevance.1,15, 16 The dynamic Q angle is affected by the position of the hip from above and the foot below during weight-bearing activities. The alignment of the hip and the foot is particularly critical at 30 degrees of knee flexion when the patella should be engaging in the trochlea. Many individuals with PFP have “squinting” patellae and an associated internal rotation of the femur, which has been hypothesized to cause tightness in the tensor fascia latae muscle and weakness of the gluteus medius muscle. Evidence in the literature of poor hip and pelvic control is limited, although there is some support that the hip abductor and rotator strength is decreased in individuals with PFP sufferers.17–19 However, others claim that hip abductor and external rotator strength is no different in PFP subjects and healthy control subjects.20 In addition, soft-tissue flexibility of various structures in the lower limb such as iliotibial band, hamstrings, gastrocnemius, and anterior hip structures has been suggested as being a factor in PFP syndrome, but the findings are quite disparate.

Abnormal foot biomechanics such as excessive, prolonged, or late pronation, which alters tibial and even entire lower limb rotation at varying times through range, has been proposed to adversely affect PF joint mechanics.15,21, 22 Intrinsic and extrinsic causes of abnormal foot position exist. The intrinsic causes relate to static foot postures such as forefoot and rearfoot varus and valgus. The extrinsic causes relate to the foot being lateral to the weight-bearing line, such as genu valgus and internal rotation of the femur, or the weight being borne on the lateral aspect of the foot, such as tibial varum. However, one research group has conflicting conclusions about the influence of foot pronation in subjects with PFP, suggesting that statically increased rearfoot varus may be a contributing factor in PFP,23 whereas dynamically, individuals with PFP do not demonstrate excessive foot pronation or tibial internal rotation compared with asymptomatic individuals.24

The most common cause of PFP cited in the literature is quadriceps muscle weakness particularly of the vastus medialis oblique (VMO). Ideally, the synergistic relation between the VMO and vastus lateralis (VL) should maintain the alignment of the patella in the femoral trochlea, especially in the first 30 degrees of knee flexion, before the patella is fully engaged in the trochlea. It has been proposed that this balanced activation of the VMO and VL is disrupted in patients with PFPS. The issue of whether the disruption is in part a motor control dysfunction has been investigated by Mellor and Hodges,25 who found that synchronization of motor unit action potentials is reduced in subjects with PFP (38%) compared with control subjects (90%). However, the evidence to support an imbalance in the activation of the vasti (either decreased activation of VMO or enhanced activation of VL) is contentious.26–29 Differences in methodology (particularly with respect to the use of electromyography [EMG]) and the inherent heterogeneity in the PFPS population may account for some of the inconsistencies in study results.

Although there is inconclusive evidence to support or refute an imbalance in the magnitude of vasti activation in patients with PFPS, disrupted activation of the vasti may take the form of delayed activation of the VMO relative to the VL. It has been hypothesized that the VMO, which has a smaller cross-sectional area than the VL, must receive a feed-forward enhancement of its excitation level to track the patellar optimally.30,31 Many studies that have examined individuals with PFPS have supported this hypothesis, by demonstrating that the EMG activity and reflex onset time of the VMO relative to the VL is delayed, when compared with asymptomatic individuals.32–34 However, the issue remains controversial in the literature, with some studies demonstrating no differences in EMG onsets,27,28, 35, 36 but a more recent study by Cowan and colleagues34 found that although the majority of subject with PFP have a delayed onset of VMO relative to VL on a stair-stepping task (67% concentrically, 79% eccentrically), there were still some subjects whose VMO preceded VL activation. In addition, these investigators found that some of the control subjects (no history of PFP) exhibited a delayed onset of the VMO relative to the VL (46% concentrically and 52% eccentrically) on the stair-stepping task. Cowan and colleagues’34 study may clarify some of the discrepancies found in the literature with regards to timing. The stratification of the groups occurs only when there are sufficient subject numbers to tease out the difference. Some of the earlier studies may not have a statistical significance because the power calculations had not been done and there were too few subjects.

Individuals with PFP not only demonstrate a delay in the onset of VMO relative to the VL but also relative to the prime mover (tibialis anterior and soleus, respectively) after postural perturbation where subjects were required to rock back on their heels or go up on their toes in response to a light stimulus.37 In control subjects, the VMO preceded the prime mover and was activated with the VL.37 This feed-forward strategy used by the central nervous system to control the patella can be restored by physical therapy rehabilitation strategies directed at altering muscle recruitment in functional movements.38

TREATMENT

PFP is not a self-limiting condition, so it is important to identify strategies that will alleviate the symptoms of this often chronic condition. The majority of patients with PFP respond to nonoperative (physical therapy) management, which aims to not only improve patellar tracking through active (quadriceps or VMO retraining) and passive (realignment procedures such as tape, brace, stretching) interventions but also improve lower-limb mechanics both proximally by pelvic muscle training and distally by enhancing foot function with orthotics or muscle training. Initially, the clinician needs to be able to significantly reduce the patient’s symptoms. This is often achieved by taping or bracing the patella. One group of investigators suggests that bracing may even prevent the development of PFP in athletic individuals.39

Patellar taping should unload painful structures to enable the patient to be pain-free while doing activities. Theoretically, using tape could also provide a sustained stretch of the tight lateral structures, making use of the creep phenomenon, which occurs when a constant low load is applied to viscoelastic material such as the lateral retinacular tissues. Length of soft tissues can be increased with sustained stretching, and the magnitude of increased displacement is dependent on the duration of the applied stretch,40 although there have been no studies to show changes in retinacular tissue length after taping.

Short-term pain reduction does occur with patellar taping and bracing41–45 (Level of Evidence I), and research continues to focus on mechanisms to explain this pain relief. Two randomized, clinical trials did not find any benefits of using a medial glide tape while doing physical therapy in addition to physical therapy intervention.46,47 The problem with both these studies is that the beneficial effect of tape was not established, and the tape was applied only for the physical therapy session, not while the individuals were doing other potentially painful weight-bearing activities.

A few studies have evaluated the effects of patellar taping and bracing on radiographic patellar alignment in patients with PFPS with conflicting results. Although improvements have been noted in some studies,48 other studies failed to find radiologic evidence of changed patellar position.43 A number of factors including different measurement procedures (weight bearing vs. non–weight bearing), taping techniques, and subject attributes may contribute to the disparate results.

Although no evidence has been reported that patellar tape can change the activation magnitude of the VMO or VL,49 there is evidence that taping the patella can alter the onset timing of the VMO relative to the VL during stair ambulation.50,51 Cowan and colleagues50 used a randomized, crossover design in which participants with PFPS were required to complete the stair-stepping task under 3 experimental conditions: no tape, therapeutic tape, and control tape (Level of Evidence I). During the stair-stepping task, the application of the therapeutic tape was found to alter the temporal characteristics of VMO and VL activation, whereas the control tape had no effect. Taping the patella has also been shown to significantly increase isokinetic quadriceps torque,41,42 as well as knee extensor moments and power during a vertical jump and lateral step up.52

In addition to taping the patella, taping the lateral thigh has been proposed as a technique to improve the balance of VL and VMO activity. The tape is applied firmly in a horizontal direction across the VL muscle belly and the midthigh level to inhibit the activity of VL. This premise has been investigated only in asymptomatic individuals in whom it was found that inhibitory tape significantly reduced the EMG activity of VL compared with no tape or placebo tape in a stair descent task.53

There seems to be consensus in the literature that bracing and/or taping that provides immediate pain relief should be used as an adjunct to treatment in conjunction with muscle retraining. VMO retraining to restore the dynamic stability of the patella is one of the mainstays of PFP rehabilitation programs. Traditionally, open chain exercises have been proposed to improve quadriceps muscle imbalance. There are 3 main open kinetic chain exercises: (1) isometric knee extension, (2) inner range knee extension (terminal or short-arc knee extension), and (3) straight leg raises. All 3 utilize knee flexion less than 30 degrees to minimize PF joint contact stress. The available evidence suggests that the VMO is not preferentially activated compared with VL during isometric knee extension, inner range quadriceps, or straight leg raises, regardless of the hip rotation bias.54–57 In fact, all studies that evaluate both the straight leg raise and isometric quadriceps setting have shown less EMG activity in the single-joint extensors during a straight leg raise (even when resistance is applied) than during the isometric quadriceps setting exercise. The addition of hip rotation (internal or external) does not appear to have a beneficial effect on the activation of VMO.56,57 Mixed results have been reported regarding the addition of hip adduction on the relative activation of VMO and VL, with some authors finding that hip adduction enhances the VMO/VL ratio,58 whereas others found no benefit.54,55

However, there is increasing evidence that weight bearing or closed chain training is effective in preferentially activating the vasti. Stensdotter and colleagues59 found in asymptomatic subjects that closed chain knee extension promoted a more simultaneous onset of EMG activity of the 4 different muscle portions of the quadriceps compared with open chain. In open chain, rectus femoris had the earliest EMG onset, whereas the VMO was activated last with smaller amplitude than in closed chain. These authors conclude that closed kinetic chain exercise promotes a more balanced initial quadriceps activation than open kinetic chain exercise. This supports the finding of Escamilla and coworkers,60 who found that open kinetic chain exercises produced more rectus femoris activity, with closed chain exercises producing more vasti activity. Closed kinetic training allows simultaneous training not only of the vasti but also the gluteals and trunk muscles to control the limb position in weight bearing.

A stable pelvis minimizes unnecessary stress on the knee. Training of the gluteus medius (posterior fibers) decreases hip internal rotation and the consequent valgus vector force that occurs at the knee. However, the evidence supporting the effect of hip muscle training alone on PFP symptoms is quite limited, with most studies being single-case studies with no long-term follow-up.61,62 If the patient exhibits internal rotation and adduction of the femur during weight-bearing activities, indicating poor gluteal control, it has been suggested that taping the gluteals may improve the stability of the pelvis. Kilbreath and coworkers63 recently demonstrated improved hip extension in a group of stroke patients after gluteal taping. The subjects who had experienced a stroke between 2 and 11 years ago walked at 2 different speeds (self-selected and fast) under three different conditions (control, therapeutic, and placebo tape). With the therapeutic tape in situ, subjects went from 3 degrees of hip flexion in the control situation to 11-degree extension in self-selected walking speed and 8 degrees in fast walking. No difference was found with placebo tape. The authors conclude that the shortened gluteal musculature could work more effectively and improve hip extension. Further research needs to be done to validate the use of gluteal tape to improve pelvic stability in patients with PFP.

Some promising evidence in the literature has evaluated the pain-reducing effect of orthotics in subjects with PFP who exhibit excessive pronation.64–66 Both hard and soft orthotics are effective in relieving symptoms but do not have much effect in changing foot or lower limb alignment, so the mechanism of pain reduction remains unknown (Level of Evidence III).67 Appropriate flexibility exercises are often included in the treatment regimen. Only 1 study has examined the effectiveness of a stretching program to decrease PFP symptoms.68 Peeler and Anderson68 recently found that after 3 weeks of quadriceps muscle stretching in weight bearing that there was a significant reduction in PFP (Level of Evidence III).

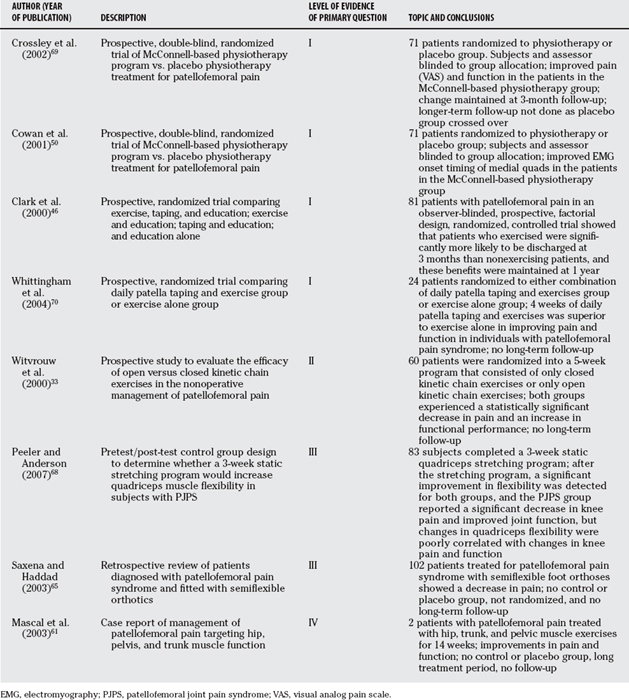

What is evident from the literature is that no one treatment is effective for PFP because it is a multifactorial problem that requires a multimodal approach. Strong evidence has been recorded in the literature that a McConnell-based physical therapy program is successful in managing PFP.69,70 This includes patellar taping, patellar mobilizations, specific quadriceps and gluteal exercises often with biofeedback, and stretching for the anterior hip structures and hamstrings. A robust, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of a McConnell-based physical therapy program in 71 patients with PFP demonstrated that the physical therapy group responded significantly better to treatment and had greater improvements in average pain, worst pain, and functional activities (Level of Evidence I). The physical therapy treatment changed the onset timing of VMO relative to VL during stair-stepping and postural perturbation tasks. At baseline in both the placebo and treatment groups, the VMO came on significantly later than the VL. After treatment, there was no change in muscle onset timing of the placebo group, but in the physiotherapy group, the onset of VMO and VL occurred simultaneously during concentric activity, and VMO preceded VL during eccentric activity.39,71

CONCLUSION

PFP is a multifactorial problem where it seems the symptoms are most likely to be arising from the fat pad or lateral retinaculum, which are highly nociceptive structures. A multimodal physical therapy program is effective. This consists of taping or bracing to relieve pain, performing weight-bearing exercises for the quadriceps and the gluteals, stretching the quadriceps in weight bearing, stretching the tight anterior hip structures, and in some cases, using orthotics. Table 95-2 provides a summary of recommendations for the management of PFP.

| RECOMMENDATION | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

PFP, patellofemoral pain; VMO, vastus medialis oblique.

1 Fulkerson J, Hungerford D. Disorders of the Patellofemoral Joint, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1990.

2 Lutter L. The knee and running. Clin Sports Med. 1985;4:685-698.

3 Almeida S, Williams KM, Shaffer RA, et al. Epidemiological patterns of musculoskeletal injuries and physical training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:1176-1182.

4 Heir T, Glomsaker P. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries among Norwegian conscripts undergoing basic military training. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1996;6:186-191.

5 Jones BH, Cowan DN, Tomlinson JR, et al. Epidemiology of injuries associated with physical training among young men in the army. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1993;25:197-203.

6 Milgrom C, Kerem E, Finestone A, et al. Patellofemoral pain caused by overactivity. A prospective study of risk factors in infantry recruits. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73A:1041-1043.

7 Dye SF, Vaupel GL, Dye CC. Conscious neurosensory mapping of the internal structures of the human knee without intraarticular anaesthesia. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:773-777.

8 Witonski D, Wagrowska-Danielewicz M. Distribution of substance-P nerve fibers in the knee joint of patients with anterior knee pain. A preliminary report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1999;7:177-183.

9 Bennell K, Hodges P, Mellor R, et al. The nature of anterior knee pain following injection of hypertonic saline into the infrapatellar fat pad. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:116-121.

10 Fulkerson JP, Tennant R, Jaivin JS, et al. Histological evidence of retinacular nerve injury associated with patellofemoral malalignment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;197:196-205.

11 Sanchis-Alfonso V, Rosello-Sastre E. Immunohistochemical analysis for neural markers of the lateral retinaculum in patients with isolated symptomatic patellofemoral malalignment. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:725-731.

12 Bierdert R, Lobenhoffer P, Lattermann C, et al. Free nerve endings in the medial and posteromedial capsuloligamentous complexes: Occurences and distribution. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:68-72.

13 Goodfellow J, Hungerford D, Zindel M. Patellofemoral joint mechanics & pathology. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58B:287-299.

14 Gresalmer R, McConnell J. The Patella. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen, 1998.

15 Powers CM. The influence of altered lower-extremity kinematics on patellofemoral joint dysfunction: A theoretical perspective. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:639-646.

16 McConnell J. The physical therapist’s approach to patellofemoral disorders. Clin Sports Med. 2002;21:363-387.

17 Brindle TJ, Mattacola C, McCrory J. Electromyographic changes in the gluteus medius during stair ascent and descent in subjects with anterior knee pain. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003:244-251.

18 Ireland ML, Willson JD, Ballantyne BT, et al. Hip strength in females with and without patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:671-676.

19 Robinson RL, Nee RJ. Analysis of hip strength in females seeking physical therapy treatment for unilateral patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2007;37:232-238.

20 Piva SR, Goodnite EA, Childs JD. Strength around the hip and flexibility of soft tissues in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2005;35:793-801.

21 Buchbinder R, Naparo N, Bizzo E. The relationship of abnormal pronation to chondromalacia patellae in distance runners. J Am Podiatr Assoc. 1979;69:159-161.

22 Tiberio D. The effect of excessive subtalar joint pronation on patellofemoral mechanics: A theoretical model. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1987;9:160-165.

23 Powers CM, Maffucci R, Hampton S. Rearfoot posture in subjects with patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1995;22:155-160.

24 Powers CM, Chen PY, Reischl SF, Perry J. Comparison of foot pronation and lower extremity rotation in persons with and without patellofemoral pain. Foot Ankle Int. 2002;23:634-640.

25 Mellor R, Hodges PW. Motor unit synchronization is reduced in anterior knee pain. J Pain. 2005;6:550-558.

26 Boucher JP, King MA, Lefebvre R, et al. Quadriceps femoris muscle activity in patellofemoral pain syndrome. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:527-532.

27 Morrish GM, Woledge RC. A comparison of the activation of muscles moving the patella in normal subjects and in patients with chronic patellofemoral problems. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1997;29:43-48.

28 Powers CM, Landel RF, Perry J. Timing and intensity of vastus muscle activity during functional activities in subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. Phys Ther. 1996;76:946-955.

29 Souza DR, Gross M. Comparison of vastus medialis obliquus: Vastus lateralis muscle integrated electromyographic ratios between healthy subjects and patients with patellofemoral pain. Phys Ther. 1991;71:310-320.

30 Grabiner MD, Koh TJ, Draganich LF. Neuromechanics of the patellofemoral joint. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1994;26:10-21.

31 Wickiewicz TL, Roy RR, Powell PL, et al. Muscle architecture of the human lower limb. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;179:275-283.

32 Voight M, Weider D. Comparative reflex response times of the vastus medialis and the vastus lateralis in normal subjects with extensor mechanism dysfunction. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:131-137.

33 Witvrouw E, Lysens R, Bellemans J, et al. Intrinsic risk factors for the development of anterior knee pain in an athletic population. A two year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:480-489.

34 Cowan SM, Bennell KL, Hodges PW, et al. Delayed onset of electromyographic activity of vastus medialis obliquus relative to vastus lateralis in subjects with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:183-189.

35 Karst GM, Willet GM. Onset timing of electromyographic activity in the vastus medialis oblique and vastus lateralis muscles in subjects with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. Phys Ther. 1995;75:813-823.

36 Grabiner MD, Koh MA, Andrish JT. Decreased excitation of vastus medialis oblique and vastus lateralis in patellofemoral pain. Eur J Exp Musculoskel Rese. 1992;1:33-39.

37 Cowan SM, Hodges PW, Bennell KL, et al. Altered vastii recruitment when people with patellofemoral pain syndrome complete a postural task. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:989-995.

38 Cowan S, Bennell K, Hodges P, et al. Simultaneous feedforward recruitment of the vasti in untrained postural tasks can be restored by physical therapy. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:553-558.

39 Van Tiggelen D, Witvrouw E, Roget P, et al. Effect of bracing on the prevention of anterior knee pain—a prospective randomized study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:434-439.

40 Taylor D, Dalton J, Seaber A. Visco-elastic properties of muscle-tendon units. The biomechanical effect of stretching. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:300.

41 Conway A, Malone T, Conway P. Patellar alignment/tracking alteration: Effect on force output and perceived pain. Isokinet Exerc Sci. 1992;2:9-17.

42 Handfield T, Kramer J. Effect of McConnell taping on perceived pain and knee extensor torques during isokinetic exercise performed by patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. Physiotherapy Canada. 2000:39-44.

43 Worrell T, Ingersoll CD, Bockrath-Pugliese K, et al. Effect of patellar taping and bracing on patellar position as determined by MRI in patients with patellofemoral pain. J Athl Train. 1998;33:16-20.

44 Selfe J, Richards J, Thewlis D, Kilmurray S. The biomechanics of step descent under different treatment modalities used in patellofemoral pain. Gait Posture. 2008;27:258-263.

45 Powers CM, Ward SR, Chen YJ, et al. Effect of bracing on patellofemoral joint stress while ascending and descending stairs. Clin J Sport Med. 2004;14:206-214.

46 Clark DI, Downing N, Mitchell J, et al. Physiotherapy for anterior knee pain: A randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:700-704.

47 Kowall MG, Kolk G, Nuber GW, et al. Patellar taping in the treatment of patellofemoral pain. A prospective randomized study. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:61-66.

48 Herrington L. The effect of corrective taping of the patella on patella position as defined by MRI. Res Sports Med. 2006;14:215-223.

49 Cowan SM, Hodges PW, Crossley KM, Bennell KL. Patellar taping does not change the amplitude of electromyographic activity of the vasti in a stair stepping task. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:30-34.

50 Cowan SM, Bennell KL, Crossley KM, et al. Physiotherapy treatment changes motor control of the vastii in patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS): A randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:S89.

51 Gilleard W, McConnell J, Parsons D. The effect of patellar taping on the onset of vastus medialis obliquus and vastus lateralis muscle activity in persons with patellofemoral pain. Phys Ther. 1998;78:25-32.

52 Ernst GP, Kawaguchi J, Saliba E. Effect of patellar taping on knee kinetics of patients with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:661-667.

53 Tobin S, Robinson G. The effect of McConnell’s vastus lateralis inhibition taping technique on vastus lateralis and vastus medialis obliquus activity. Physiotherapy. 2000;26:173-183.

54 Karst GM, Jewett PD. Electromyographic analysis of exercises proposed for differential activation of medial and lateral quadriceps femoris muscle components. Phys Ther. 1993;73:286-299.

55 Cuddeford T, Williams AK, Medeiros JM. Electromyographic activity of the vastus medialis oblique and vastus lateralis muscles during selected exercises. J Man Manip Ther. 1996;4:10-15.

56 Cerny K. Vastus medialis oblique/vastus lateralis muscle activity ratios for selected exercises in persons with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. Phys Ther. 1995;75:672-682.

57 Mirzabeigi E, Jordan C, Gronley JK, et al. Isolation of the vastus medialis oblique muscle during exercise. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:50-53.

58 Hodges P, Richardson CA. The influence of isometric hip adduction on quadriceps femoris activity. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1993;25:57-62.

59 Stensdotter AK, Hodges PW, Mellor R, et al. Quadriceps activation in closed and in open kinetic chain exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:2043-2047.

60 Escamilla RF, Fleisig GS, Zheng N, et al. Biomechanics of the knee during closed kinetic chain and open kinetic chain exercises. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1998;30:556-569.

61 Mascal CL, Landel R, Powers C. Management of patellofemoral pain targeting hip, pelvis, and trunk muscle function: 2 case reports. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2003;33:647-660.

62 Cibulka MT, Threlkeld-Watkins J. Patellofemoral pain and asymmetrical hip rotation. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1201-1207.

63 Kilbreath SL, Perkins S, Crosbie J, McConnell J. Gluteal taping improves hip extension during stance phase of walking following stroke. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:53-56.

64 Eng JJ, Pierrynowski MR. Evaluation of soft foot orthotics in the treatment of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Phys Ther. 1993;73:62-68.

65 Saxena A, Haddad J. The effect of foot orthoses on patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93:264-271.

66 Johnston LB, Gross MT. Effects of foot orthoses on quality of life for individuals with patellofemoral pain syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:440-448.

67 Nester CJ, van der Linden ML, Bowker P. Effect of foot orthoses on the kinematics and kinetics of normal walking gait. Gait Posture. 2003;17:180-187.

68 Peeler J, Anderson JE. Effectiveness of static quadriceps stretching in individuals with patellofemoral joint pain. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17:234-241.

69 Crossley K, Bennell K, Green S, et al. Physical therapy for patellofemoral pain: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:857-865.

70 Whittingham M, Palmer S, Macmillan F. Effects of taping on pain and function in patellofemoral pain syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34:504-510.

71 Cowan SM, Bennell KL, Crossley KM, et al. Physical therapy alters recruitment of the vasti in patellofemoral pain syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:1879-1885.