Water and sodium balance

AVP and the regulation of osmolality

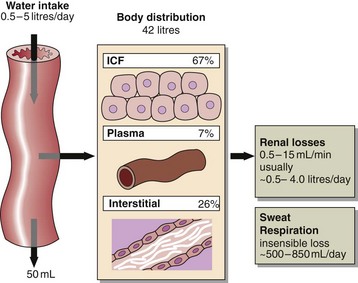

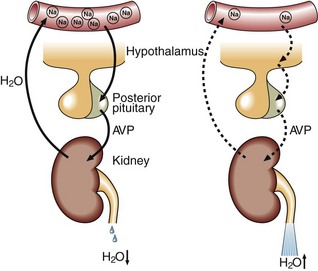

Specialized cells in the hypothalamus sense differences between their intracellular osmolality and that of the extracellular fluid, and adjust the secretion of AVP from the posterior pituitary gland. A rising osmolality promotes the secretion of AVP while a declining osmolality switches the secretion off (Fig 7.2). AVP causes water to be retained by the kidneys. Fluid deprivation results in the stimulation of endogenous AVP secretion, which reduces the urine flow rate to as little as 0.5 mL/minute in order to conserve body water. However, within an hour of drinking 2 L of water, the urine flow rate may rise to 15 mL/minute as AVP secretion is shut down. Thus, by regulating water excretion or retention, AVP maintains normal electrolyte concentrations within the body.

Sodium

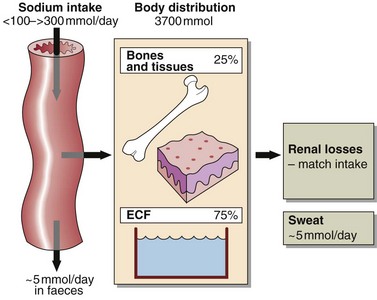

The total body sodium of the average 70 kg man is approximately 3700 mmol, of which approximately 75% is exchangeable (Fig 7.3). A quarter of the body sodium is termed non-exchangeable, which means it is incoporated into tissues such as bone and has a slow turnover rate. Most of the exchangeable sodium is in the extracellular fluid. In the ECF, which comprises both the plasma and the interstitial fluid, the sodium concentration is tightly regulated at around 140 mmol/L.

Urinary sodium output is regulated by two hormones:

Aldosterone

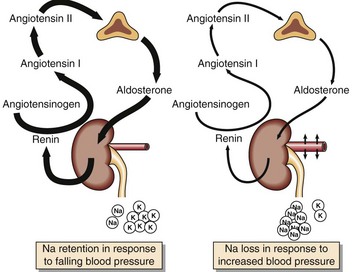

Aldosterone decreases urinary sodium excretion by increasing sodium reabsorption in the renal tubules at the expense of potassium and hydrogen ions. Aldosterone also stimulates sodium conservation by the sweat glands and the mucosal cells of the colon, but in normal circumstances these effects are trivial. A major stimulus to aldosterone secretion is the volume of the ECF. Specialized cells in the juxtaglomerular apparatus of the nephron sense decreases in blood pressure and secrete renin, the first step in a sequence of events that leads to the secretion of aldosterone by the glomerular zone of the adrenal cortex (Fig 7.4).