W

Wake-up test. Intraoperative awakening to allow assessment of spinal cord function during spinal surgery. Has also been used to assess cerebral function during basilar artery clipping.

Warfarin sodium. Oral anticoagulant drug, first synthesised in 1944. Rapidly absorbed by mouth and almost totally protein-bound. Competes with vitamin K in the synthesis of coagulation factors II, VII, IX and X in the liver; therefore requires 1–2 days for its effect to develop. Also inhibits protein C and S. Metabolised in the liver and excreted in urine and faeces. Half-life is about 30 h. Dosage is adjusted according to results of coagulation studies: the International Normalised Ratio (INR) is maintained at about 2–3 for prophylaxis and treatment of DVT, PE, transient ischaemic attacks and in patients with atrial fibrillation at high risk of embolisation; 3–4.5 for recurrent DVT/PE, cardiac and arterial prostheses. The usual maintenance dose is 3–9 mg/day. The INR is usually checked daily or on alternate days initially, but thereafter up to every 2 months, depending on the response.

Drugs causing hepatic enzyme induction (e.g. rifampicin, phenytoin) reduce its effect. If the second drug is withdrawn without reducing the dose of warfarin, haemorrhage may occur. Effects may be enhanced by drugs that displace it from protein-binding sites, e.g. sulphonamides, NSAIDs. Emergency treatment of haemorrhage due to excessive warfarin effect involves use of vitamin K injection (up to 5 mg iv) and the administration of factors II, VII, IX and X (prothrombin complex concentrate, or fresh frozen plasma).

heart valves: maintain warfarin therapy for short (under 30 min) surgery, with fresh frozen plasma available. Otherwise, stop warfarin 3 days preoperatively, and start heparin infusion 24 h later (about 15 000 units/12 h), maintaining activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) at 2–3 times normal. Stop heparin 6 h preoperatively, and check INR and APTT 1 h preoperatively. Surgery may be delayed, or plasma administered, if INR exceeds 1.5. Restart warfarin as soon as possible postoperatively, or heparin if nil by mouth for over 48 h. Extra precautions have been suggested for prosthetic mitral valves, since the risk of emboli is greater than for other valves: aspirin 75 mg or dipyridamole 300 mg/day is started when warfarin is stopped. Heparin is restarted 6–12 h postoperatively until able to take warfarin. Increasingly, low-mw heparin is being used to ‘bridge’ coagulation perioperatively instead of unfractionated heparin.

heart valves: maintain warfarin therapy for short (under 30 min) surgery, with fresh frozen plasma available. Otherwise, stop warfarin 3 days preoperatively, and start heparin infusion 24 h later (about 15 000 units/12 h), maintaining activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) at 2–3 times normal. Stop heparin 6 h preoperatively, and check INR and APTT 1 h preoperatively. Surgery may be delayed, or plasma administered, if INR exceeds 1.5. Restart warfarin as soon as possible postoperatively, or heparin if nil by mouth for over 48 h. Extra precautions have been suggested for prosthetic mitral valves, since the risk of emboli is greater than for other valves: aspirin 75 mg or dipyridamole 300 mg/day is started when warfarin is stopped. Heparin is restarted 6–12 h postoperatively until able to take warfarin. Increasingly, low-mw heparin is being used to ‘bridge’ coagulation perioperatively instead of unfractionated heparin.

[Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, where warfarin was developed]

Warren, John C (1778–1856). Professor of Surgery and Anatomy at Harvard Medical School. It was at Warren’s invitation that Wells gave his demonstration of N2O anaesthesia, which ended in failure. Later, at Morton’s first public demonstration of diethyl ether, Warren performed the surgery.

Washout curves. Graphs displaying the exponential decline in concentration of a substance that is continuously being removed from a system. The substance may be ‘washed out’ by blood flow, in the case of dye dilution cardiac output measurement, or by ventilation of the lungs, in the case of nitrogen washout. The term is sometimes used to describe any negative exponential process.

Water, see Fluid balance; Fluids, body

Water balance, see Fluid balance

Water diuresis. Diuresis occurring about 15 min after the intake of a large volume of hypotonic fluid. Absorption of the fluid is followed by inhibition of vasopressin secretion and by increased urinary water loss.

Water intoxication, see Hyponatraemia

Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome, see Adrenocortical insufficiency

Waters bag, see Anaesthetic breathing systems

Waters, Ralph Milton (1883–1979). US anaesthetist; became Assistant Professor of Surgery in charge of anaesthetics at University of Wisconsin, leading to his appointment as the first university Professor of Anaesthesia in the USA (1933). Was the first to establish a resident training programme in anaesthesia and the first to use cyclopropane clinically (1930). Re-examined chloroform toxicity, advocated the use of inflatable cuffs on tracheal tubes, and was involved in many aspects of anaesthesia, including the use of thiopental and endobronchial intubation. Designed his ‘to-and-fro’ cannister for CO2 absorption in anaesthetic breathing systems, and the Waters airway, a metal oropharyngeal airway with a side-arm for attachment to a gas supply.

Waterton, Charles (1783–1865). Squire of Walton Hall, Yorkshire; made his first voyage to South America in 1812. Described the preparation of curare and the blowpipes, darts, bows and arrows used by the Indians of the Amazon and Orinoco basins. Experimented with the drug on his return to England, and maintained life in a paralysed donkey by employing IPPV. Published details of his work and travels in Wanderings in South America (1825).

Watt. Unit of power. One watt (W) = 1 joule per second (J/s).

Waveforms. Repetitive patterns plotted against time produce waveforms that may be complex (e.g. ECG) or simple, as in the sine wave. All complex waveforms may be mathematically deconstructed into component sine waves (Fourier analysis). For any sine wave, there is oscillation about a mean value, the maximal displacement from which is the amplitude. The number of complete oscillations per second is the frequency, and the distance between successive points at the same stage of the cycle is the wavelength. Waveform monitoring is very common in anaesthesia and intensive care, e.g. cardiovascular (ECG, intravascular pressures, plethysmography), respiratory (rate, depth, pattern), ventilatory (gas flow, pressure), neurological (intracranial pressure, EEG, nerve conduction studies).

Weaning from ventilators. Process of gradual withdrawal of ventilatory support. Usually presents no problems after less than a few days’ ventilation; following longer periods or poor baseline respiratory function, rapid weaning is less likely.

• Criteria for beginning weaning vary considerably; the following have been suggested:

absence of major organ or system failure, particularly CVS.

absence of major organ or system failure, particularly CVS.

precipitating illness is successfully treated.

precipitating illness is successfully treated.

absence of severe infection or fever.

absence of severe infection or fever.

minimal sedation with absence of severe pain.

minimal sedation with absence of severe pain.

– arterial blood gases are near premorbid values.

– respiratory rate < 35 breaths/min.

– maximal negative inspiratory airway pressure attainable exceeds –25 cmH2O.

– airway occlusion pressure greater than 6 cmH2O below atmospheric.

– tidal volume > 5 ml/kg.

– minute ventilation < 10 litres.

– vital capacity > 10–15 ml/kg.

– FRC > 50% of predicted value.

After long-term ventilation, scoring systems have been proposed to predict difficult weaning, reflecting FIO2 and level of PEEP required, lung compliance, work of breathing, temperature, pulse rate and arterial BP. Other risk factors for difficult weaning include: increased airway resistance (e.g. COPD, tracheal stenosis); respiratory muscle fatigue; hypoxia and acidosis; cardiac failure; confusion; sleep deprivation; prolonged illness; and critical illness polyneuropathy/myopathy.

humidification of inspired air.

humidification of inspired air.

sitting the patient up increases FRC and diaphragmatic efficiency.

sitting the patient up increases FRC and diaphragmatic efficiency.

the lowest FIO2 necessary to maintain adequate oxygenation should be used, to decrease the risk of absorption atelectasis, and possibly promote hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Inappropriately high FIO2 should be avoided in CO2-retaining patients with COPD.

the lowest FIO2 necessary to maintain adequate oxygenation should be used, to decrease the risk of absorption atelectasis, and possibly promote hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction. Inappropriately high FIO2 should be avoided in CO2-retaining patients with COPD.

a simple T-piece is often used when IPPV has been for a short duration. A 30 cm expiratory limb and fresh gas flow of twice minute volume will prevent indrawing of room air with lowering of FIO2, and rebreathing. Use should be limited in duration as the loss of physiological PEEP may increase the risk of atelectasis.

a simple T-piece is often used when IPPV has been for a short duration. A 30 cm expiratory limb and fresh gas flow of twice minute volume will prevent indrawing of room air with lowering of FIO2, and rebreathing. Use should be limited in duration as the loss of physiological PEEP may increase the risk of atelectasis.

CPAP is often preferred, especially following high PEEP, in ARDS and in left ventricular dysfunction.

CPAP is often preferred, especially following high PEEP, in ARDS and in left ventricular dysfunction.

– IMV and variants: the set mandatory ventilator rate is decreased as patient spontaneous rate increases. Spontaneous breaths are usually augmented with inspiratory pressure support (see below). Allows closer monitoring of recovery and reduces complications of IPPV.

– airway pressure release ventilation, inspiratory pressure support, pressure-regulated volume control ventilation, mandatory minute ventilation, inspiratory volume support, high-frequency ventilation and variants and negative pressure ventilation have also been used.

non-invasive positive pressure ventilation.

non-invasive positive pressure ventilation.

extubation may be performed when the patient is stable and able to protect the airway. Excessive secretions may be removed via minitracheotomy. Elective formation of a tracheostomy may assist in weaning by reducing dead space, allowing easy access for tracheobronchial toilet and permitting a reduction in sedation.

extubation may be performed when the patient is stable and able to protect the airway. Excessive secretions may be removed via minitracheotomy. Elective formation of a tracheostomy may assist in weaning by reducing dead space, allowing easy access for tracheobronchial toilet and permitting a reduction in sedation.

Work of breathing is increased by demand and expiratory valves and tubing, especially using CPAP and IMV circuits through certain ventilators. Modern ventilators provide circuits of low resistance, with minimal exertion required to open demand valves.

Wedge pressure, see Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure

Wegener’s granulomatosis. Necrotising small vessel granulomatous vasculitis, particularly involving pulmonary and renal vessels. Features include non-specific symptoms (malaise, weight loss, fever, night sweats), nasal discharge and ulceration, pleurisy, haemoptysis, myalgia, arthralgia and renal failure. Subglottic stenosis may result in difficult airway management. Progression is variable but some cases rapidly develop MODS requiring ICU admission for IPPV and haemofiltration/dialysis. The diagnosis may be suspected clinically if both lungs and kidneys are involved, supported by detecting antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) in plasma. Tissue biopsies are frequently unhelpful as granulomatous deposits are difficult to locate in life, even in the kidney.

Treatment of organ failure is supportive; Wegener’s itself is treated with cyclophosphamide and corticosteroids. Eventual remission is complete in approximately 75% of cases.

Weight. The force exerted upon a body due to gravity. Equals the product of the mass of the body and local acceleration due to gravity. The weight of a body of mass 1 kilogram is 1 kilogram weight (kilogram force).

Weil’s disease, see Leptospirosis

Wells, Horace (1815–1848). US dentist, present at Colton’s demonstration of N2O in Hartford, Connecticut on 10 December 1844. Noticing that a member of the audience (Samuel Cooley) had knocked his shin under the influence and felt no pain, he suggested its use for dental extraction. Wells had one of his own teeth pulled out by John Riggs the following day, whilst breathing N2O prepared by Colton. Performed successful painless extractions in several patients over subsequent days, before his ill-fated demonstration of N2O before Warren at Harvard Medical School, Boston, at which the patient complained of pain and Wells was denounced as a fraud. Continued to practise dentistry, but became increasingly disillusioned as acceptance of N2O was overshadowed by Morton’s discovery of diethyl ether. Later a chloroform addict, he committed suicide by cutting his femoral artery whilst in prison.

[Samuel Cooley (1809–?), druggist’s assistant; John Riggs (1810–1885), US dentist]

Wenckebach phenomenon, see Heart block

Wernicke’s encephalopathy, see Vitamin deficiency

Wheezing. Sustained, polyphonic whistling respiratory sound produced usually during expiration, indicating narrowing of the natural or artificial airway. Distinguished from stridor by being lower-pitched and composed of a wider range of frequencies, and usually represents smaller airways’ obstruction. May be generalised or localised.

narrowed bronchi: bronchospasm, bronchiolitis, pulmonary oedema, aspiration of gastric contents, inhaled foreign body, airway tumour, pneumothorax, coughing or straining (causing airway collapse via increased intrathoracic pressure).

narrowed bronchi: bronchospasm, bronchiolitis, pulmonary oedema, aspiration of gastric contents, inhaled foreign body, airway tumour, pneumothorax, coughing or straining (causing airway collapse via increased intrathoracic pressure).

Bronchospasm should be diagnosed only when other causes have been excluded.

Whistle discriminator. Obsolete device used to confirm correct attachment of N2O and O2 supplies to an anaesthetic machine by virtue of the differently pitched sounds produced when the gases flow through it, because of their different densities.

WHO Surgical Safety Checklist, see World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist

Whole bowel irrigation. Technique of GIT decontamination used in the treatment of poisoning and overdoses, especially with metals and delayed-release drug preparations, although convincing evidence for its efficacy is lacking. Employs large volumes (up to 2 l/h in adults) of polyethylene glycol administered via mouth or nasogastric tube until the rectal effluent is clear. Should not be used in obtunded patients or in the presence of gastrointestinal ileus, intestinal obstruction, perforation or haemorrhage. Electrolyte disturbances have not been reported with polyethylene glycol, unlike preoperative bowel preparations, which were studied initially.

Wilcoxon signed rank test, see Statistical tests

Willis, circle of, see Cerebral circulation

‘Wind-up’. Phenomenon in which the electrophysiological response of central pain-carrying neurones (e.g. those in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord) increases with repetitive stimulation of peripheral nociceptors; in addition the receptive fields of the individual neurones expand. Partly explains the hyperalgesia and allodynia that may occur in acute and chronic pain states, and the concept of plasticity within the CNS by which painful input may alter the connections and activity of central neurones. Excitatory amino acids (e.g. glutamate) are thought to be involved, acting especially via NMDA receptors, although other receptor types are also thought to be involved, as are other modulating substances such as dynorphin, substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide. Intracellular accumulation of these and other substances via gene induction is also thought to be important. Prevention of wind-up is a central tenet of preventive and pre-emptive analgesia.

Withdrawal of treatment in ICU. Cessation of all or individual components of treatment is a frequent mode of death in the ICU. In general, treatment is withdrawn when it has ceased or failed to achieve the benefits for which it was employed. It usually takes place when there is confirmed brainstem death or the patient’s prognosis is poor with no prospect of returning to a reasonable quality of life. Occasionally, even a treatment that might produce benefit may be withheld or withdrawn if the patient is suffering from a terminal illness. Withdrawal of each medical treatment should be considered from the patient’s perspective in the context of benefit. Withdrawal of treatment should be regarded as permitting the dying process to continue, rather than ‘causing’ death.

the wishes (often unknown) of an unconscious patient.

the wishes (often unknown) of an unconscious patient.

the validity and legality of decisions made by a surrogate.

the validity and legality of decisions made by a surrogate.

the definition of a good quality of life.

the definition of a good quality of life.

the nature of medical treatment, i.e. feeding, hydration.

the nature of medical treatment, i.e. feeding, hydration.

consideration of religious beliefs.

consideration of religious beliefs.

• Before withdrawal of treatment, the following should be undertaken/sought:

the views of the family, the legal status of any appointed representative and advance decision of the patient.

the views of the family, the legal status of any appointed representative and advance decision of the patient.

If brainstem death is diagnosed and organ donation is intended, withdrawal of support takes place after organ removal (beating heart donation). Otherwise, observations, monitoring, drugs, procedures and routine care (apart from symptom palliation) can be withdrawn once clinical staff and the patient’s family have reached a consensus. IPPV may continue unchanged during this period or the technique of ‘terminal weaning’ of ventilation may be employed, in which inspired oxygen concentration is reduced to an FIO2 of 0.21. Feeding/antibiotics are stopped and inotropic support terminated. Sedation and analgesia are maintained, or increased if the patient becomes distressed, to ensure a peaceful, humane, comfortable and dignified death for the patient and to diminish distress for the family. Privacy is important for the patient and family during the dying process. Organ donation after death is known as non-beating heart donation.

Where the condition that precipitated the patient’s admission to ICU involves suspicious circumstances (e.g. poisoning, assault), contact with the coroner is advised before treatment withdrawal. Whatever the circumstances, good clinical records should be kept.

See also, Ethics; Euthanasia; Mental Capacity Act; Palliative care

Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome. Condition in which a congenital accessory connection between the atria and ventricles conducts more rapidly than the atrioventricular (AV) node, but has a longer refractory period. An atrial extrasystole finds the accessory bundle still refractory, but when the impulse passes via the AV node to the ventricles, the accessory bundle has recovered, and can conduct the impulse back to the atria. Circular conduction can continue with resultant SVT. AF and atrial flutter may also occur, but less commonly.

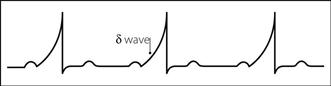

The ECG classically shows a short P–R interval and wide QRS complexes with δ waves (Fig. 174). A positive QRS complex in lead V1 denotes type A (accessory bundle on the left side of the heart); if negative, type B (right side of heart).

Anaesthetic management of known cases should be directed at avoiding increased sympathetic activity, including that due to anxiety. Antiarrhythmic drugs should be continued perioperatively. Drugs causing tachycardia (e.g. atropine, ketamine, pancuronium) should be avoided. Isoflurane is probably the volatile anaesthetic agent of choice as it suppresses accessory pathway conduction.

Treatment of arrhythmias (including perioperatively) follows standard measures. Digoxin and verapamil may increase impulse conduction through accessory pathways by blocking conduction through the AV node, and should be avoided. Management of established cases includes electrophysiological assessment (accessory pathway mapping), long-term prophylactic therapy (e.g. with flecainide, sotalol) and radiofrequency ablation of the accessory pathway.

Fig. 174 ECG showing δ waves

Work. Product of force and the distance through which it acts. Work is done whenever the point of application of a force moves in the direction of that force. Also expressed as the product of the change in volume of a system and the pressure against which this change occurs (e.g. stroke work). SI unit is the joule.

Work of breathing, see Breathing, work of

World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA). Founded in 1955 at the first World Congress of Anaesthesiologists in The Hague, Holland, in order to promote anaesthetic education, research, training and safety standards throughout the world. World Congresses are held every 4 years (since 1960). Membership is via 40 anaesthetic societies in different countries. Has three regional sections: Latin American, Asia/Australian and European. The last of these was founded in 1966 and renamed the Confederation of European National Societies of Anaesthesiology in 1998.

World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist. Tool introduced by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2008 to improve patient safety during surgery, and implemented within the NHS in 2010. Consists of a series of questions confirming the main issues that may hinder safe operating or result in adverse outcomes, arranged in three phases:

• Before the surgical procedure (‘time out’): introduction of all team members; patient’s identity, site and type of procedure; ASA physical status, expected blood loss; any anticipated critical events; need for antibiotics or imaging/specialised equipment (including monitoring); sterility of instruments.

Wrist, nerve blocks. Used for minor surgery to the hand.

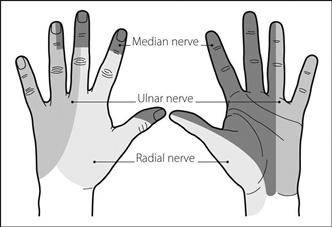

• The following nerves are blocked (Fig. 175):

median nerve (C6–T1): at the level of the proximal skin crease, it lies between flexor carpi radialis tendon laterally and palmaris longus tendon medially. With the wrist dorsiflexed, 2–5 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected just lateral to the palmaris longus tendon, at a depth of 0.5–1 cm.

median nerve (C6–T1): at the level of the proximal skin crease, it lies between flexor carpi radialis tendon laterally and palmaris longus tendon medially. With the wrist dorsiflexed, 2–5 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected just lateral to the palmaris longus tendon, at a depth of 0.5–1 cm.

ulnar nerve (C7–T1): lies under flexor carpi ulnaris tendon proximal to the pisiform bone, medial and deep to the ulnar artery. At the level of the ulnar styloid process, a needle is inserted between flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and the ulnar artery, and 2–5 ml solution injected. The two cutaneous branches of the nerve may be blocked by subcutaneous infiltration around the ulnar side of the wrist from the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon.

ulnar nerve (C7–T1): lies under flexor carpi ulnaris tendon proximal to the pisiform bone, medial and deep to the ulnar artery. At the level of the ulnar styloid process, a needle is inserted between flexor carpi ulnaris tendon and the ulnar artery, and 2–5 ml solution injected. The two cutaneous branches of the nerve may be blocked by subcutaneous infiltration around the ulnar side of the wrist from the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon.

radial nerve (C5–T1): its branches pass along the radial and dorsal aspects of the wrist. At the level of the proximal skin crease, a needle is inserted lateral to the radial artery, and 3 ml solution injected. Infiltration around the radial border of the wrist blocks superficial branches.

radial nerve (C5–T1): its branches pass along the radial and dorsal aspects of the wrist. At the level of the proximal skin crease, a needle is inserted lateral to the radial artery, and 3 ml solution injected. Infiltration around the radial border of the wrist blocks superficial branches.

Fig. 175 Cutaneous innervation of the hand