Chapter 22 Vulvovaginitis, Sexually Transmitted Infections, and Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Normal Physiology and Microecology of the Vagina

Normal Physiology and Microecology of the Vagina

INVESTIGATION OF VAGINAL DISCHARGE

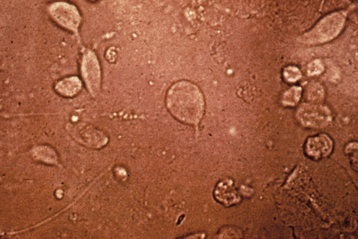

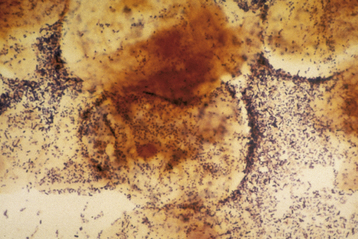

A wet-mount preparation of the discharge should be evaluated. Using a cotton-tipped applicator, a sample of vaginal discharge from the posterior fornix is suspended in 2 mL of normal saline. A drop of this solution is placed on a glass slide, covered with a coverslip, and examined under the microscope. Motile trichomonads may be seen on this type of wet mount (Figure 22-1). Also, epithelial cells with irregular, granular edges (clue cells) are indicative of clumped bacteria on the cell wall and are highly suggestive of BV if present in more than 20% of epithelial cells (Figure 22-2). If the cells are not sufficiently separated, an aliquot of fluid is placed in a drop of saline or 10% to 20% KOH (to eliminate cellular and other debris while leaving mycelia) and examined microscopically, to visualize the pseudohyphae or spores of Candida infection. In complicated or atypical cases, bacterial and yeast cultures are required.

Vaginal Discharge Etiology

Vaginal Discharge Etiology

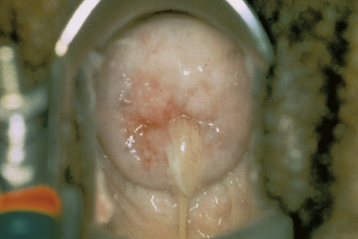

Up to 90% of cases of vaginitis appear to be caused by three conditions. Bacterial vaginosis accounts for 40% to 50%, vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) for 20% to 25%, and trichomoniasis for 15% or less of cases. Mucopurulent cervicitis (“mucopus”) caused by chlamydia, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, mycoplasma, or BV-associated bacteria (see Figure 22-6) may also cause vaginal irritation and discharge. Less common types include atrophic vaginitis (overgrowth with aerobic or anaerobic microflora in the absence of lactobacilli and with hypoestrogenized tissues), foreign-body vaginitis, genital ulcer diseases such as herpes and syphilis, desquamative vaginitis (most commonly group B streptococcal overgrowth), and lichen planus. Irritation from sexual activity and allergen-containing substances can also mimic infectious vaginitis.

FIGURE 22-3 Cottage cheese or curd-like appearance of vaginal discharge is typical of vulvovaginitis due to yeast.

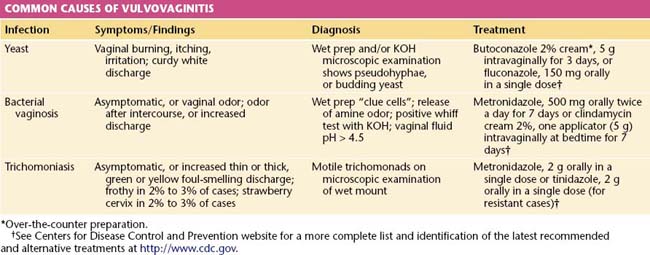

Standard clinic or office diagnosis of vaginitis requires a working microscope, pH paper, KOH, saline solution, slides, coverslips, and the ability to recognize an amine odor (whiff test). In many settings, these rudimentary tools are not available. Newer, inexpensive “point of care” products can detect vaginal sialidase, amines, and proline aminopeptidase and other biomarker substances or nucleic acid–based tests. In difficult or refractory cases, additional tests for vaginal agents may be used such as culture for Trichomonas vaginalis, Candida, mycoplasmas, or predominant vaginal aerobic bacterial. Table 22-1 lists the common causes, characteristics, and treatments for vulvar and vaginal infections.

VULVOVAGINAL CANDIDIASIS

The classic presentation of VVC includes vaginal itching, burning, irritation, and possibly postvoiding dysuria. The discharge is usually odorless, has a pH of less than 4.7, and is thick or curdy with the appearance of cottage cheese (Figure 22-3). Examination often shows vulvovaginal erythema, with evidence of acute or chronic excoriation.

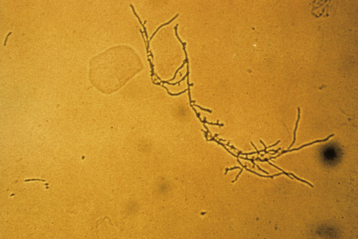

Microscopic examination of a wet-mount preparation is positive for budding yeast cells, pseudohyphae, or mycelial tangles (Figure 22-4) in 50% to 70% of cases. Women with suggestive clinical findings but absent wet preparation evidence may benefit from fungal culture.

TRICHOMONIASIS

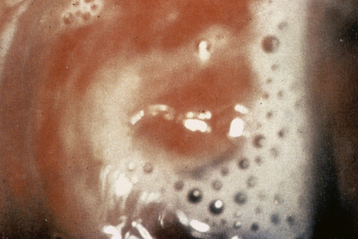

Trichomoniasis (cervicitis, vaginitis, and urethritis) is caused by the protozoan T. vaginalis. About 50% of cases in women and men are asymptomatic. Symptomatic infection is classically manifested by a green-yellow, frothy vaginal discharge (Figure 22-5), with a “musty” odor. Dyspareunia, vulvovaginal irritation, and occasionally dysuria may be present. Male partners are often asymptomatic even though they demonstrate nongonococcal urethritis on direct examination.

Metronidazole (2 g single oral dose) is the recommended treatment (see Table 22-1). Patients should not consume alcohol for 2 days after treatment. Although metronidazole is not known to be teratogenic in recommended dosages, it has been traditionally avoided during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy. Prompt early treatment during pregnancy relieves symptoms, reduces the risk for HIV transmission, and may improve pregnancy outcomes. Trichomoniasis should be treated before vaginal surgical procedures.

Metronidazole resistance is increasing and may be overcome by using tinidazole (now available in the United States; see Table 22-1) or using higher doses of metronidazole (2 g daily for 7 days). Reversible side effects of metronidazole include an “Antabuse-like reaction” with alcohol exposure, neutropenia, and peripheral neuropathy. Higher-dose treatment for resistant trichomoniasis in pregnancy should be prescribed with caution in consultation with experts.

Other Common Sexually Transmitted Infections

Other Common Sexually Transmitted Infections

CHLAMYDIA

Chlamydia trachomatis is an obligate intracellular bacteria that grows in vitro only in tissue culture. It can infect the columnar epithelium of the endocervix, urethra, endometrium, fallopian tubes, and rectum. This organism can persist for long periods in an asymptomatic carrier state. There is no vaccine available, and even though chlamydia antibodies are produced, they do not protect against reinfection. Because about 70% of infected females and 50% of infected males have no symptoms, it is very difficult to diagnose and treat this “hidden” infection. In those cases in which symptoms are present, the clinical manifestations of lower genital tract chlamydia infection are (1) mucopurulent cervicitis or mucopus, which is a yellow discharge coming from a swollen, red, friable cervix that bleeds easily (see Figure 22-3), and (2) acute urethritis with dysuria but minimal frequency and urgency and a negative urine culture.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

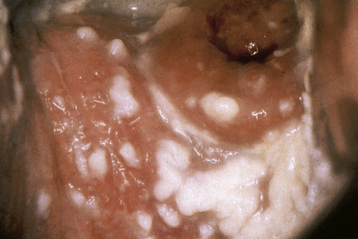

SIGNS

Clinical signs in women with laparoscopically confirmed PID most frequently include lower abdominal tenderness, with or without rebound tenderness; uterine and adnexal tenderness to palpation and motion; and findings of mucopurulent cervicitis (Figure 22-6). Fever is the least common finding. A pregnancy test should be performed when symptoms or signs of pregnancy are present.

DIAGNOSIS

PID should be diagnosed and treated empirically in sexually active young women and women with risk factors who have uterine and adnexal or cervical motion tenderness. The CDC cautions that PID is unlikely if the patient does not have a mucopurulent cervical discharge (see Figure 22-6) or white blood cells on vaginal wet mount. Abnormal findings that make the diagnosis more secure include fever, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, elevated C-reactive protein, and documented cervical infection with gonorrhea or chlamydia.

TREATMENT

The need for hospitalization is an important treatment decision (Box 22-1). Women with severe infections or an inability to take and absorb oral antibiotics (nausea, vomiting, possible peritonitis, and ileus) should be hospitalized and treated until clinical improvement is evident. Similarly, women with a questionable diagnosis, pregnancy, or unreliability, should be admitted initially and treated with parenteral agents to ensure compliance and treatment efficacy, as should those who fail to respond to outpatient therapy.

BOX 22-1 Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Clinical Criteria for Hospitalization and Parenteral Treatment

Table 22-2 lists antibiotic regimens for inpatient and outpatient management, as recommended by the CDC. Other recommended and alternative treatments are listed on their website, http://www.cdc.gov.

TABLE 22-2 CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION RECOMMENDED TREATMENTS FOR PELVIC INFLAMMATORY DISEASE, 2006∗

| Regimen A | Regimen B |

|---|---|

| INPATIENT TREATMENT | |

IM, intramuscularly; IV, intravenously.

∗ See Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for verification of latest recommended dose and a more complete list of alternative treatments at http://www.cdc.gov.

PREVENTION

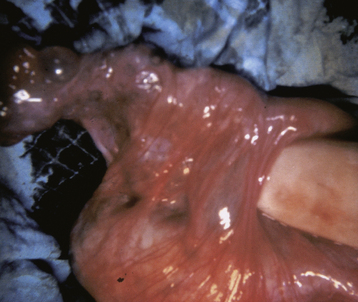

To minimize the risk for reinfection, partners for the past 60 days should be identified, diagnosed, and given specific treatment or treated empirically for both chlamydial infection and gonorrhea. Most infected male partners are asymptomatic. This practice should minimize recurrence and reinfection that can lead to permanent adhesions (Figure 22-7).

Other Clinical Issues Related to STIs

Other Clinical Issues Related to STIs

TUBO-OVARIAN ABSCESs (TOA)

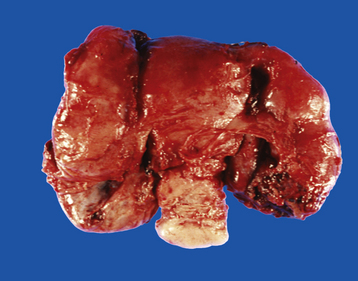

Rupture of a TOA causes spreading peritonitis, which can be rapidly lethal in the absence of expeditious surgical drainage, antimicrobial treatment, and systemic vital organ support. TOAs may cause considerable long-term morbidity from irreversible tubal and ovarian damage, with subsequent infertility, chronic pain, and gonadal failure. Rarely, death results from uncontrolled sepsis. Figure 22-8 shows a gross postoperative specimen of a uterus with bilateral TOAs.

FIGURE 22-8 Gross appearance of bilateral tubo-ovarian abscesses.

(From Kumar V, et al: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 7th ed. Philadelphia, Saunders, 2005.)

A TOA is distinguished from uncomplicated endometritis or salpingitis by the presence of a tender inflammatory adnexal mass. Confirmation of the diagnosis may require the use of imaging techniques such as ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging, as depicted in Figure 22-9. Drainage of a TOA under ultrasonic guidance can be both diagnostic and therapeutic. Laparotomy or laparoscopy may be required to distinguish TOAs from inflammatory complexes, twisted or infected adnexal structures, or pelvic abscesses from other sources (e.g., appendicitis or diverticulitis). If there is doubt regarding the diagnosis, laparoscopy should be performed promptly. If laparoscopy or laparotomy is performed, the TOA or pyosalpinx should be drained (extraperitoneally if possible), followed by copious irrigation.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases: Treatment guidelines. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 55:1-92, 2006. Updates and ordering available online at: http://www2.cdc.gov/nchstp_od/piweb/stdorderform.asp or by telephone at 404-639-3311.

McClelland R.S. Trichomonas vaginalis infection: Can we afford to do nothing? J Infect Dis. 2008;197:487-489.

Paavonen J., Lehtinen M. Introducing human papillomavirus vaccines: Questions remain. Ann Med. 2008;40:162-166.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Recommendations for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) of adults and adolescents in healthcare settings. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77:819-824.

Vanvranken M. Prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:1827-1832.

Reproductive Tract Infections

Reproductive Tract Infections