10 Vomiting blood, black stools, blood per rectum, occult bleeding

Case

A 67-year-old male presents to the emergency department with a history of a massive haematemesis (fresh blood) over 12 hours. He was unwell and also complained of syncopal episodes. He had no previous episodes. There was a past history of hepatitis C infection. Alcohol consumption was 120 g/day, which he ceased 2 years back.

Introduction

Five different clinical situations are commonly encountered:

The approach to management of these clinical situations forms the basis of this chapter.

Vomiting Blood

The main causes of haematemesis are listed in Box 10.1. So how do these patients present? They may feel nauseous and even continue to vomit during the initial assessment or have symptoms related to blood loss including sweating, dizziness and confusion.

Management

Hypotension and shock

Assessment of hypovolaemia involves simple bedside clinical observations. The patient may be clammy and sweaty with cold peripheries and a fast thready pulse. There may be associated confusion. The blood pressure will be low, often under 90 mmHg systolic. If any of these signs are seen, resuscitation should commence immediately. At least two large-bore intravenous cannulae should be inserted into large peripheral veins. A central venous line should be placed in high-risk cases (see below). Rapid infusion of isotonic saline followed by a plasma expander such as Haemaccel® should be commenced and blood samples should be drawn urgently for full blood count, coagulation screen, blood group and cross-matching of four to six units of packed cells, and urea, electrolytes and liver function tests.

Patients with a gastrointestinal bleed have lost ‘whole blood’ and there is, therefore, logic in transfusing them with whole blood (Box 10.2). In practice, however, donated blood is separated into packed cells and other products, such as platelets and plasma, which may be used in different clinical situations. Thus, in current clinical practice, patients with a significant bleed are given packed cells alternating with a plasma expander such as Haemaccel if they are hypovolaemic and packed cells alone if they are normovolaemic but anaemic. The aim of transfusion is to restore circulating blood volume so that the blood pressure is normal and to correct anaemia so that the oxygen carrying capacity of the blood is satisfactory. This generally means maintaining a haemoglobin level of approximately 100 g/L. One unit of packed cells will increase the haemoglobin level by 10 g/L (haematocrit by 3%).

Source of the bleed

Endoscopy

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the single most useful test. If performed within 24 hours of presentation, the cause of bleeding will be found in 90–95% of patients (Figs 10.1 to 10.3). Furthermore, it may permit the endoscopist to perform therapeutic interventions that in turn may arrest the bleeding or minimise the chance of further bleeding. It requires considerable expertise, especially in the situation of an actively bleeding lesion, and is not without some risk.

So who should be endoscoped and when should it be done? This decision is more easily made if consideration is given to why the endoscopy is being done. First, the aim is to make an accurate diagnosis. Secondly, a prognosis for further bleeding may be given, based on the endoscopic findings. Finally, a bleeding lesion or one at high risk of re-bleeding may be able to be treated. However, if the patient is not in a high-risk category, it may not be necessary to do an emergency procedure. In general terms, endoscopy should always be done within 24 hours but, for patients considered being at ‘high risk’, particularly if there is a possibility of oesophageal varices, emergency endoscopy should be arranged once the patient has been adequately resuscitated.

Risk factors for greater morbidity and mortality from haematemesis are now well known and are listed in Box 10.3.

Box 10.3 High risk features in patients with haematemesis

Common causes of haematemesis

Oesophageal varices

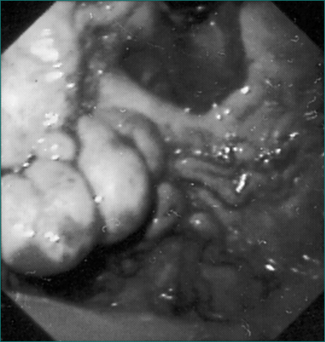

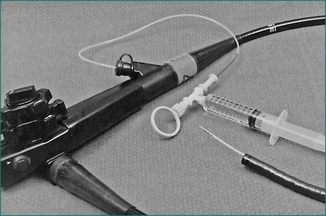

If bleeding oesophageal varices are found during endoscopy, rubber band ligation is the current treatment of choice. Bleeding can be controlled in 80–90% of cases with a relatively low risk of complications. If passage of the rubber band ligating device mounted on the tip of the endoscope is not feasible or if equipment and expertise for rubber band ligation are not available, injection sclerotherapy may be performed (Fig 10.4). This involves direct injection of a sclerosant such as ethanolamine oleate or sodium tetradecyl sulfate into the varices. Injection sclerotherapy has a very high success rate in controlling the bleeding, although with a greater risk of complications including sepsis, oesophageal stricture and mediastinitis.

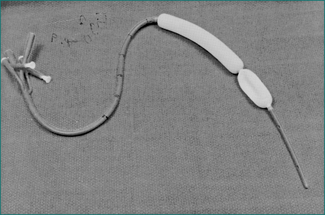

If ongoing aggressive management is decided upon, the next step should be to insert a Minnesota or Sengstaken-Blakemore tube (balloon tamponade) into the oesophagus and stomach (Fig 10.5). This can be passed through the nose, preferably with the patient anaesthetised, though in practice the tube is often inserted in an emergency situation without a general anaesthetic.

Mortality from bleeding oesophageal varices is still very high despite the advances in endoscopic and radiological management. The severity of the underlying liver disease is the main determinant of outcome. For those patients who do respond well to the initial banding or sclerotherapy, careful follow-up is required with ongoing endoscopic treatment at 1–3 weekly intervals until the varices are obliterated. These treatments can be given on a day-case basis. This treatment approach should be supplemented by a beta-blocking agent such as propranolol.

Gastric or duodenal ulceration

The discovery that most peptic ulcers are caused by an infection in the stomach, courtesy of the bacterium H. pylori, has led to the frequent adoption of antibacterial therapy (Ch 5). Treatment of H. pylori in patients with peptic ulcer markedly reduces the risk of subsequent ulcer relapse and associated bleeding, without the need for long-term maintenance drug treatment. The current regimens will work in up to 80% of patients, eradicating the infection, healing the ulcer and markedly reducing the risk of ulcer recurrence. In the immediate aftermath of a haematemesis, clinicians may choose to use the simpler drug regimen of an H2-receptor antagonist or proton pump inhibitor alone to heal the ulcer and then, when the patient has stabilised and out of hospital, follow on with H. pylori eradication, or treat the infection as soon as the patient can eat at the same time as giving acid suppression drug therapy.

If a peptic ulcer is found in a patient receiving NSAID therapy, these drugs should be discontinued at least in the short term and, ideally, long term. Ulcer healing can then proceed along the lines outlined above. Some patients cannot manage without regular NSAIDs and, in that case, long-term prophylactic treatment with a proton pump inhibitor should be considered. Misoprostol can also be used to protect against recurrent gastric ulceration in a patient on NSAIDs. The COX-2 inhibitors can be used in these patients in place of traditional NSAIDs, but the risk of further bleeding is only reduced, not abolished, by this substitution and ideally these patients should also remain on a proton pump inhibitor.

Other causes of haematemesis

Ulcerative oesophagitis that bleeds sufficiently to cause an overt haematemesis is usually severe and requires aggressive acid suppression. Rarely, a chronic ulcer in a Barrett’s oesophagus may bleed (Ch 1). By far the most effective treatment for oesophageal ulceration is with the proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole, esomeprazole, rabeprazole or pantoprazole. Long-term therapy is likely to be needed. Laparoscopic fundoplication may also be considered as an alternative to long-term medical treatment.

Role of surgery in bleeding peptic ulcers

The choice of operation will vary according to the clinical circumstances. In most instances, an oversewing of the bleeding artery is all that is performed since it is assumed that medical therapy afterwards will deal with the ulcer effectively. In some instances, especially if there is a history of recurrent bleeding or ulceration despite medical therapy, a more definitive operation will be performed, such as a partial gastrectomy for a gastric ulcer (Ch 6).

Discharge from hospital

Patients with bleeding varices comprise the highest risk group and these patients should remain in hospital for up to a week, during which time the risk of massive re-bleeding is highest. Treatment also has to be directed to the underlying liver disease and its complications (Ch 24). Patients with high-risk peptic ulcers are at increased risk of re-bleeding for at least 72 hours after the initial bleed. Discharge from hospital is reasonable after 4–5 days if the patient’s course in hospital has been uncomplicated.

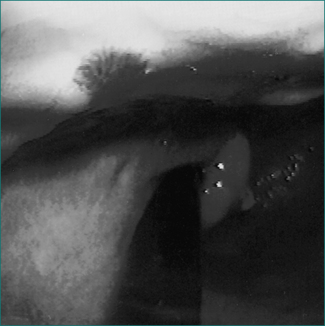

Passing Melaena Alone

Most cases of melaena are due to bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract, mainly from peptic ulceration. Oesophageal varices rarely present in this way, because they bleed so briskly that bright red haematemesis occurs long before melaena is seen. However, some patients with portal hypertension ooze blood more slowly from dilated blood vessels in the stomach (portal gastropathy, Fig 10.2) or intestine (portal enteropathy), and melaena may be the first sign.

Bright Red Blood Per Rectum

Causes of rectal bleeding in patients under the age of 40 years are listed in Box 10.4. In older patients, the differential diagnosis is wider, and more serious conditions such as colorectal cancer are much more prevalent (Box 10.4).

A careful history should be taken, focusing on the following points:

Examination should include a check for an abdominal mass arising from the colon and a careful inspection of the anal area to look for any signs of an anal fissure. A rectal examination should be done, feeling with the finger for any palpable lumps and any local tenderness. A proctoscopy and/or rigid or flexible sigmoidoscopy should follow. This is an extremely useful test in this situation, especially if done acutely. If a bleeding source is clearly identified, such as bleeding haemorrhoids or fissure, further immediate investigation may be avoided. If no lesion is found or if a possible source is seen but with no evidence of recent bleeding (e.g. non-bleeding haemorrhoids), further investigation will be necessary in most instances. Remember that haemorrhoids are common and it is dangerous to assume that they are the source of the bleeding, especially in a more elderly patient, if no evidence of recent bleeding is seen at the time of the examination.

Causes of rectal bleeding

Specific points related to the individual causes of rectal bleeding are given below.

Haemorrhoids

These are particularly associated with constipation and straining at stool. They are vascular cushions that form in the venous plexuses at the anorectal junction. Bleeding is typically intermittent. Blood is seen on the toilet paper, as a splash in the toilet bowl or on the outside of the stools. For minor bleeding, reassurance is all that is necessary after the clinical evaluation has been performed. Attention to diet and treatment of associated constipation is appropriate. If bleeding is more persistent or recurrent, local treatment of the haemorrhoids can be given. The most common interventions include injection of the haemorrhoids with sclerosant, and rubber band ligation. For more severe prolapsing haemorrhoids, haemorrhoidectomy is appropriate (Ch 12).

Anal fissure

Treatment again is directed towards the underlying constipation. Fibre supplements and stool softeners are used and the patient is encouraged to avoid straining at stool. Glyceryl trinitrate ointment will relax anal spasm and allow some fissures to heal. This conservative approach will work in many cases but for more chronic recurrent fissures, surgical intervention is necessary (Ch 12).

Rectal polyps

If these are seen at sigmoidoscopy, the patient should be fully prepared for a colonoscopy so that a search for more proximal polyps can be made. Most polyps can be removed at colonoscopy using a snare or biopsy forceps. Since approximately 90% of colorectal cancers arise from preexisting adenomatous polyps, the rationale for polyp excision is not only control of the rectal bleeding but also cancer prevention. If the polyps are found at histology to be adenomatous, colonoscopic surveillance is warranted, especially in patients with multiple polyps or large polyps, as there is an increased risk of new polyp formation and colorectal cancer. Repeat examinations should be done at 3- to 5-yearly intervals in most cases (Ch 22).

Angiodysplasia or vascular ectasia of the bowel

These vascular lesions are increasingly common with advancing age. About 25% of patients over the age of 60 years have angiodysplasia but only a small proportion bleed. Vascular lesions are most commonly found in the right colon, but are occasionally found in the small intestine or left colon. They may present with occult bleeding leading to iron deficiency anaemia or with more brisk bleeding leading to moderate or even massive rectal bleeding. The cause of these lesions is unclear. They are dilated, thin-walled vascular lesions in the submucosa of the colon and may develop in response to chronic pressure changes, especially in the right colon. Bleeding is typically intermittent and ceases spontaneously, only to recur at a later date in most patients. Sometimes the bleeding is torrential and emergency intervention is required. If detected at colonoscopy, argon plasma coagulation, injection therapy or laser may be used to stop the bleeding. At angiography, injection of vasopressin or embolisation techniques may be used successfully. In some patients, surgical intervention, often a right hemicolectomy, may prove necessary. Delineation of the extent of angiodysplasia by investigation, such as capsule endoscopy for small bowel involvement, is appropriate before surgical intervention is planned.

Inflammatory bowel disease

Ulcerative proctitis may present as rectal bleeding without any associated change in bowel habit, though most patients also have diarrhoea. The condition may be due to ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease and is easily diagnosed by sigmoidoscopy (Ch 15). If there are other symptoms suggesting the presence of more proximal disease, the patient may need a colonoscopy. Local treatment of proctitis with steroid enemas, 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas or oral sulfasalazine treatment works well in most patients. Resistant cases need more aggressive immunosuppression with high-dose oral steroids.

Ischaemic colitis

This usually occurs in the setting of widespread peripheral vascular disease or cardiac disease. The rectal bleeding is often associated with mild lower abdominal cramps. Characteristic changes are seen on colonoscopy or barium enema usually at the level of the splenic flexure and descending colon because this is a watershed area in the blood supply to the colon (Fig 10.6). Treatment is conservative and the condition settles spontaneously in most cases. Some patients develop a stricture at the site of the ischaemia, which rarely requires subsequent excision (Ch 4).

Massive rectal bleeding

A rectal examination and sigmoidoscopy should start the diagnostic work-up because occasionally a local perianal cause will be found. If the findings are negative, it is appropriate to proceed to an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy so that a gastroduodenal cause is fully excluded. This can be accomplished quickly and prepares the way for more complex and invasive investigation of the small and large intestine.

Iron Deficiency Anaemia

Sometimes a high platelet count occurs in patients with chronic active blood loss.

A wide range of gastrointestinal lesions (see Box 10.5) may be responsible for the anaemia, from ulcerative oesophagitis to colonic angiodysplasia. A great concern in elderly patients is the possibility of a caecal carcinoma. Usually, distal colonic lesions or oesophageal lesions present with overt blood loss from respective ends of the gastrointestinal tract leading to haematemesis or rectal bleeding and are uncommon causes of isolated iron-deficiency anaemia. Non-bleeding lesions should also be considered. Malabsorption of iron in patients with coeliac disease, previous gastrectomy or atrophic gastritis may occur.

Positive Faecal Occult Blood Test

More invasive screening with colonoscopy may be appropriate if there is a strong family history of bowel cancer. One first-degree relative in the family with bowel cancer under the age of 55 years or two first-degree relatives with bowel cancer at any age increases the chance of the patient getting bowel cancer by three- or fourfold, compared with the general population. A colonoscopy in those with a strong family history is recommended every 5 years from the age of 40 years, or from the age of onset of the cancer in the family member less 10 years (Ch 22).

Key Points

Bleau B.L., Gostout C.J., Sherman K.E., et al. Recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer associated with adherent clot: a randomised study comparing endoscopic treatment with medical therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:1-6.

Burling D., East J.E., Taylor S.A. Investigating rectal bleeding. BMJ. 2007;15(335(7632)):1260-1262.

D’Amico G., Garcia-Pagan J.C., Luca A., et al. Hepatic vein pressure gradient reduction and prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(5):1611-1624.

Frossard J.L., Spahr L., Queneau P.E., et al. Erythromycin intravenous bolus infusion in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a randomised controlled double blind trial. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:17-23.

Hadithi M., Heine G.D., Jacobs M.A., et al. A prospective study comparing video capsule endoscopy with double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:52-57.

Kravetz D. Prevention of recurrent esophageal variceal hemorrhage: review and current recommendations. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41(suppl 3):S318-S322.

Lau J.Y., Sung J.J., Lee K.K., et al. Effect of intravenous omeprazole on recurrent bleeding after endoscopic treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:310-316.

Leontiadis G.I., Sharma V.K., Howden C.W. Proton pump inhibitors for acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (1):2006. CD002094

Manning-Dimmitt L.L., Dimmitt S.G., et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71(7):1339-1346.

McCormick P.A., Burroughs A.K., McIntyre N. How to insert a Sengstaken Blakemore tube. Br J Hosp Med. 1990;43:274-277.

Peter S., Wilcox C.M. Modern endoscopic therapy of peptic ulcer bleeding. Dig Dis. 2008;26(4):291-299.

Young G.P., St John D.J., Winawer S.J., et al. Choice of fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer screening; recommendations based on performance characteristics in population studies: a WHO (World Health Organization) and OMED (World Organisation for Digestive Endoscopy) report. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2499-2507.

Zhu A., Kaneshiro M., Kaunitz J.D. Evaluation and treatment of iron deficiency anemia: a gastroenterological perspective. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(3):548-559.