CHAPTER 33 Volar Carpal Ganglion Cysts

Use of the arthroscope for diagnosis and management of wrist disorders has evolved significantly since Roth first described the technique of wrist arthroscopy in 1988.1 The development of sophisticated optical systems and instruments specific for small joint applications has enabled the experienced wrist arthroscopist to perform complex reconstructive procedures. Wrist arthroscopy facilitates visualization of intra-articular anatomy, whereas small, motorized shavers enable resection and elimination of intra-articular and capsular lesions.

In 1995, Osterman and Raphael presented a technique for the arthroscopic treatment of ganglion cysts arising from the dorsal portion of the scapholunate interosseous ligament and manifesting as dorsal space-occupying lesions.2 The initial skepticism regarding treatment of this lesion has been quelled, and arthroscopic treatment of dorsal cysts has become routine for experienced arthroscopists. Although the anatomic origin of volar carpal ganglions has not been as well defined as for their dorsal counterparts and the location is not as consistent as for the dorsal ganglion, many of these cysts do have an intra-articular capsular origin.3–5 Arthroscopic resection of volar ganglia is an effective technique with potential advantages when compared with traditional open techniques.

ANATOMY

Ganglion cysts are saclike structures that do not have a true cellular lining. They are benign soft tissue tumors that are most commonly found in the wrist but may occur adjacent to or originating from any joint. Approximately 10% of the time, they form from tendon sheaths. They are filled with a viscous fluid that contains glucosamine, albumin, globulin, and hyaluronic acid.6 The origin of most ganglion cysts is idiopathic. Occasionally, a traumatic event precedes the development of a cyst, lending support to a possible traumatic origin of these lesions. Mathoulin’s histologic analysis of ganglion cysts indicates that the base of the cyst arises in the histologic layer between the synovium and the joint capsule.7 His group postulates that this area is exposed to stress that initiates histologic degenerative lesions, particularly mucoid degeneration. These masses are not inflammatory, and they do not arise as simple herniations from the joint capsule.6,8 Other causative factors are capsular rents caused by preexisting joint pathology, synovial fluid leakage with secondary cyst formation, and mucoid degeneration or mucin secretion stimulated by joint stress or other degenerative processes. Occult volar ganglia may also contribute to volar wrist pain without a visible or palpable mass. Symptoms may be caused by capsular injury, inflammatory changes, or local pressure.

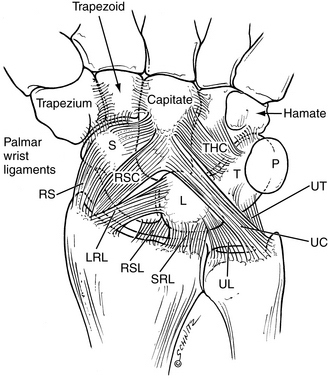

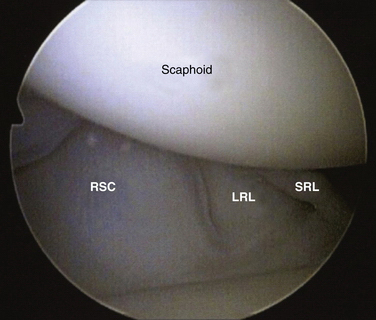

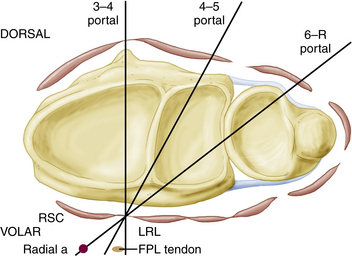

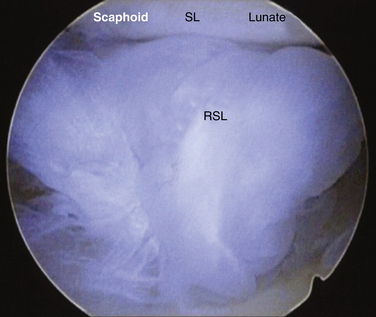

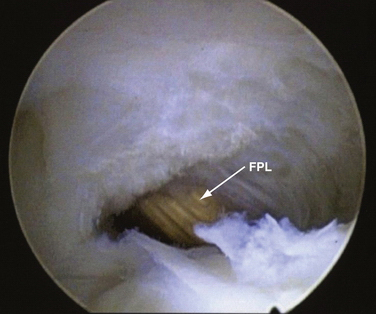

The anatomic origin of the volar ganglion cyst is not as well defined as that of its dorsal counterpart. The literature suggests a radioscaphoid, scaphotrapezial, or trapeziometacarpal (TM) joint origin.9 Volar cysts may also arise from the flexor carpi radialis (FCR) tendon sheath or other aberrant locations. Aydin and colleagues studied open excision of volar ganglions and reported that 45% arose from the radiocarpal joint, 40% from the scaphotrapeziotrapezoid (STT) joint, and 5% from the FCR sheath.10 Most arise from the radiocarpal joint, and when they do, they have a volar capsular origin from the relatively deficient area between the radioscaphocapitate (RSC) and long radiolunate (LRL) ligaments.4,11 The ligaments represent the volar extrinsic components that work in conjunction with the intrinsic and extrinsic dorsal ligaments and with the interosseous ligaments to provide wrist stability. Starting radially and proceeding in an ulnar direction, they are the RSC, the LRL, and the short radiolunate (SRL) ligaments (Fig. 33-1). When they are visualized arthroscopically, distinct clefts can be seen between these ligaments. The volar ganglion cyst can be identified in the clefts between the extrinsic radiocarpal ligaments. Ho and associates, in their study on arthroscopic resection of volar carpal ganglia, observed that 75% of the cysts arose from the interval between the RSC and LRL, and 25% originated between the LRL and SRL.3 The capsular origin can be visualized arthroscopically (Fig. 33-2).

PATIENT EVALUATION

History and Physical Examination

Most ganglion cysts occur in women in their second, third, or fourth decade of life. The onset is usually insidious, with a progressive increase in size occurring over many years. The ganglion usually manifests as a visible and palpable mass. Patients may relate a traumatic event, such as a wrist hyperextension injury, that occurred before the cyst appeared; however, most cannot recall an event or activity related to the development or appearance of the mass. The masses may be painful, and the symptoms usually are described as an aching discomfort in the region of the mass. Cosmetic dissatisfaction and concern that the mass represents a malignancy are associated complaints. A painless mass is the most frequent presenting complaint.12 Westbrook’s study of 50 patients indicated that a minority of patients presented with pain, 38% presented because of the cosmetic appearance of the mass, and 28% were concerned that the ganglion was malignant.13

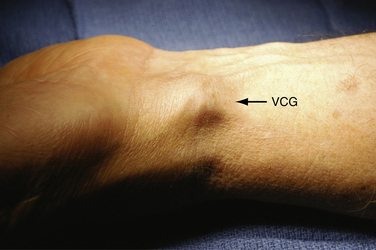

The diagnosis is easily made with visual inspection (Fig. 33-3). A 1- to 2-cm, round or ovoid mass usually manifests as a visible fullness in the interval between the FCR tendon and the radial artery. It may be unilobular or multilobular. Palpation reveals a mass that may be slightly tender. The consistency is usually soft and compressible, although chronic lesions may be quite firm. Transillumination with a penlight usually confirms the diagnosis. The differential diagnosis includes vascular lesions of the radial artery, and it is important to determine whether the mass is pulsatile or the pulsations of the radial artery can be distinguished from the mass itself. Despite the relatively easy diagnosis, it is important to exclude other causes of wrist discomfort, such as radiocarpal arthrosis, STT arthrosis, TM arthrosis, DeQuervain’s tendonitis, and FCR tendonitis. Isolated loading and stress testing of the individual joints should not produce any pain if the joint is not arthritic. The result of a Finkelstein maneuver should be negative, and there should be no tenderness of the first dorsal compartment tendons. Resisted wrist flexion should produce no pain over the FCR tendon. In patients with an occult volar ganglion cyst, the only positive physical finding may be fullness in the FCR–radial artery interval and pain with pressure in the region. Exclusion of other potential causes of volar radial wrist pain is essential.

Diagnostic Imaging

If the diagnosis is certain and the physical examination presents no confounding findings, imaging is not necessary. Wong and colleagues showed that radiographic abnormalities were diagnosed in only 13% of patients with ganglion cysts, and treatment was affected in only 1% of the cases in their study. They concluded that routine radiographs are not cost-effective.14 When desired, plain radiographs are usually sufficient as an imaging study to exclude arthrosis of the STT or TM joint. Arthroscopic management of volar ganglions is indicated only for capsular radiocarpal origins; preoperative radiographs that demonstrate arthrosis raise suspicion that the cyst may arise from a location other than the radiocarpal joint. If the nature of the mass is unclear, ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging is useful. Ultrasound is a cost-effective study that demonstrates the mass as a hypoechoic lesion. Wang and associates were able to localize the stalk-like origin of the ganglion emanating from the volar radiocarpal joint in 7 of 15 cysts. They also found that small cysts can be hypoechoic or anechoic, and not all fulfill the ultrasound criteria for simple cysts.5

TREATMENT

Indications and Contraindications

Arthroscopic management of volar ganglions is contraindicated for masses that may be coming from locations other than the radiocarpal joint capsule, such as the STT joint or the FCR sheath. Wrists that have sustained prior trauma or are excessively stiff and may present difficulty in visualization of the volar extrinsic ligaments should have their ganglia excised in an open fashion. Unusual or atypical masses that are likely not ganglions should also be treated by open excision. Recurrent ganglion cysts should be treated in an open fashion, although some surgeons have reported success in treating recurrent lesions arthroscopically.3

Conservative Management

Conservative treatment of symptomatic volar ganglion cysts is somewhat limited. Historically, conservative treatment of ganglions has included external pressure with a variety of topical agents and mechanical devices, external rubbing or massage, and closed rupture with the use of digital pressure or more violent means, such as striking the mass with a heavy book, which accounts for the designation Bible cyst. These techniques are associated with recurrence rates as high as 64%.6,15 Spontaneous resolution of ganglia occurs in approximately 50% of patients but can take many years.16 Cysts that have developed acutely or after an identifiable traumatic event should be treated with a period of splint immobilization, because the initial symptoms and the mass may resolve. More frequently, patients present with a cyst of insidious origin with a duration of many months or even years, and splinting is not an effective treatment.

Aspiration of wrist ganglia has a success rate of only 30% to 50%. The poorest results for aspiration are associated with volar ganglion cysts, and most surgeons caution against aspiration because of the risk of injury to adjacent neurovascular structures such as the radial artery and the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve.12,17,18 A 47% recurrence rate after aspiration was reported in Dias and Buchs’ study, but recurrence did not correlate with patients’ satisfaction with treatment.16 Aspiration is offered to patients who desire cyst resolution but want to avoid a more involved surgical procedure. Physicians should be certain that adjacent neurovascular structures are separate from the mass and that there is no possibility that the volar mass represents a lesion of vascular origin. Patients should be warned that the failure rate with aspiration is high and that recurrence is likely.

Arthroscopic Technique

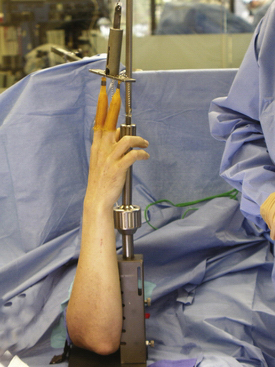

Arthroscopic excision of volar ganglion cysts starts with a standard arthroscopic setup. The arm is exsanguinated, and a proximal tourniquet is used. Traction is applied by means of sterile finger traps (Fig. 33-4). The method used to provide traction should not interfere with the ability to convert to an open procedure. A sterile traction tower offers full access to the dorsal and volar wrist, and if the need to convert to open ganglionectomy arises, the tower can be removed and an open procedure performed without compromising sterility.

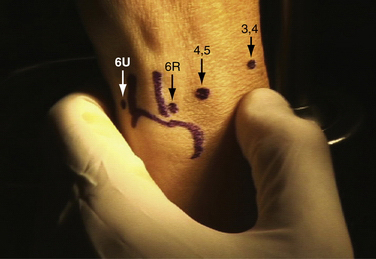

After traction is applied, standard arthroscopic portals are marked (Fig. 33-5). The outer margins of the volar ganglion should be palpated and marked (Fig. 33-6). The skin landmarks are outlined to confirm that the mass has been eliminated and decompressed.

This procedure is commonly performed with the 3-4 portal as a viewing portal and a 4-5 portal as an operative portal. In cadaver experiments, this combination was identified as being most effective for access to the volar capsular origin of the cyst (Fig. 33-7), and it was safest in regard to injury to neurovascular and tendon elements volar to the wrist capsule (Vella and Greenberg, unpublished data).

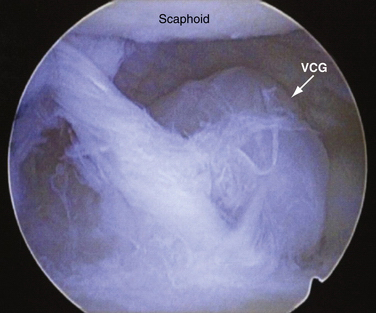

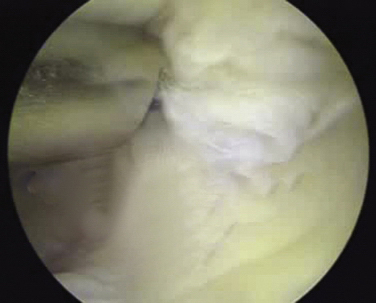

After the diagnostic portion of the procedure is completed, a full-radius resector is introduced into the 4-5 portal. The shaver is used to remove any proliferative synovium that is present. Frequently, the ligamentous interval between the RSC and LRL ligaments is obscured by the vascular leash known as the radioscapholunate ligament or ligament of Testut. The shaver is used to resect this vascular leash so that the volar capsule can be easily seen (Fig. 33-8).

At this point, a lobular structure representing the origin of the ganglion is visualized (Fig. 33-9). This is usually in the ligamentous interval on the volar capsule. Xanthomatous changes consistent with degeneration or mucinous changes may be present. If the cyst is not obvious, external pressure on the volar mass usually produces an outpouching that can be dynamically seen entering the joint in the RSC and LRL interval. This is especially true in cases of occult volar ganglion cysts.

After the origin is identified, the full-radius resector is used to carefully resect the capsular origin of the mass (Fig. 33-10). As the cyst base is removed, a distinct fluid blush is seen as the ganglion fluid decompresses into the radiocarpal joint (Fig. 33-11). This fluid movement can be enhanced by external pressure on the cyst. Resection continues until a window measuring approximately 1 × 1 cm is created (Fig. 33-12). The flexor pollicis longus tendon is visualized. A blunt probe can be passed through the created capsular defect into the cyst body and can be palpated. Passage of an instrument along this course safely avoids neurovascular structures.

FIGURE 33-10 A full-radius resector introduced through the 4-5 portal has excellent access to the origin of the ganglion cyst.

After the cyst is decompressed, the procedure is complete. Arthroscopic equipment is removed. Portal incisions are closed with nonabsorbable suture. A dressing is applied to place compression on the volar radial wrist. The postoperative dressing and splint are removed at 2 weeks postoperatively. Range-of-motion exercises and modalities to control edema are initiated, with resumption of activities as tolerated. Most patients are back to full, unrestricted use at 6 weeks postoperatively.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Patients remove their postoperative dressing and start gentle range-of-motion exercises as tolerated. Suture removal is performed at 10 days postoperatively. Patients who demonstrate excessive stiffness or swelling during this time should start a supervised therapy program that emphasizes range-of-motion exercises and edema control. Most patients require minimal supervised therapy. The level of patient satisfaction with the outcome of the procedure is typically high.3,7,20,21

COMPLICATIONS

Recurrence of the ganglion cyst is the most common complication. In 2003, Ho’s group published their initial results on arthroscopic resection of volar ganglia; there were no recurrences in the first five patients.11 Their subsequent publication, which summarized the treatment of 21 patients, documented two recurrences.3 This compares favorably with the reported recurrence rate for open excision, which ranges from 2% to 40% in the literature, and it is similar to recurrence rates reported for arthroscopic dorsal ganglia excisions. The 2003 study of open volar ganglionectomy by Aydin and colleagues identified a 22% recurrence rate,10 whereas Jacobs and Govaers reported a recurrence rate of 28% after open excision.19 Greenberg reported only one recurrence among his first 12 patients.20

Other potential complications related to arthroscopic volar ganglion excision are injury to neurovascular structures, notably the median nerve and the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve, and the radial artery. Tendon injuries may occur because of the proximity of the FPL during the procedure. Capsular injury may produce stiffness. Paying close attention to technique, especially keeping the shaver visualized at all times and not plunging deep to the capsule, should eliminate complications. Minor neurovascular injuries have been reported for volar ganglia excisions. In the series reported by Rocci and coworkers, arthroscopic resection of radiocarpal ganglia compared favorably with open excision, with significantly more rapid recovery times and earlier return to work.21 There were no neurovascular or tendon complications in this series.

1. Roth JH, Poehling GG, Whipple TL. Arthroscopic surgery of the wrist. Instr Course Lect. 1988;37:183-194.

2. Osterman AL, Raphael J. Arthroscopic resection of dorsal ganglion of the wrist. Hand Clin. 1995;11:7-12.

3. Ho PC, Law BK, Hung LK. Arthroscopic volar wrist ganglionectomy. Chir Main. 2006;25(suppl 1):S221-S230.

4. Kuhlmann JN, Luboinski J, Baux S, Mimoun M. Ganglions of the wrist: proposals for topographical systematization and natural history. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2003;89:310-319.

5. Wang G, Jacobson JA, Feng FY, et al. Sonography of wrist ganglion cysts: variable and noncystic appearances. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1323-1328. quiz 1330-1331

6. Gude W, Morelli V. Ganglion cysts of the wrist: pathophysiology, clinical picture, and management. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1:205-211.

7. Mathoulin C, Hoyos A, Pelaez J. Arthroscopic resection of wrist ganglia. Hand Surg. 2004;9:159-164.

8. Psaila JV, Mansel RE. The surface ultrastructure of ganglia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60:228-233.

9. Greendyke SD, Wilson M, Shepler TR. Anterior wrist ganglia from the scaphotrapezial joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17:487-490.

10. Aydin A, Kabakas F, Erer M, et al. Surgical treatment of volar wrist ganglia. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2003;37:309-312.

11. Ho PC, Lo WN, Hung LK. Arthroscopic resection of volar ganglion of the wrist: a new technique. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:218-221.

12. Thornburg LE. Ganglions of the hand and wrist. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:231-238.

13. Westbrook AP, Stephen AB, Oni J, Davis TR. Ganglia: the patient’s perception. J Hand Surg Br. 2000;25:566-567.

14. Wong AS, Jebson PJ, Murray PM, Trigg SD. The use of routine wrist radiography is not useful in the evaluation of patients with a ganglion cyst of the wrist. Hand (N Y). 2007;2:117-119.

15. Nelson CL, Sawmiller S, Phalen GS. Ganglions of the wrist and hand. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54:1459-1464.

16. Dias J, Buch K. Palmar wrist ganglion: does intervention improve outcome? A prospective study of the natural history and patient-reported treatment outcomes. J Hand Surg Br. 2003;28:172-176.

17. Nahra ME, Bucchieri JS. Ganglion cysts and other tumor related conditions of the hand and wrist, v. Hand Clin. 2004;20:249-260.

18. Wright TW, Cooney WP, Ilstrup DM. Anterior wrist ganglion. J Hand Surg Am. 1994;19:954-958.

19. Jacobs LG, Govaers KJ. The volar wrist ganglion: just a simple cyst?. J Hand Surg Br. 1990;15:342-346.

20. Greenberg JA. Arthroscopic treatment of volar carpal ganglion cysts. In: Slutsky DJ, Nagle DJ, editors. Techniques in Hand and Wrist Arthroscopy. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2007:188-190.

21. Rocchi L, Canal A, Fanfani F, Cantalano F. Articular ganglia of the volar aspect of the wrist: arthroscopic resection compared with open excision. A prospective randomised study. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2008;42:253-259.