Vision

What aspects of vision do I need to assess?

Visual testing is usually completed by the medical team as part of the assessment of the cranial nerves (S2.10). Visual acuity should be assessed by an optometrist using a Snellen eye chart. However, there are aspects of vision that are simple and relevant for the therapist to assess:

Visual fields

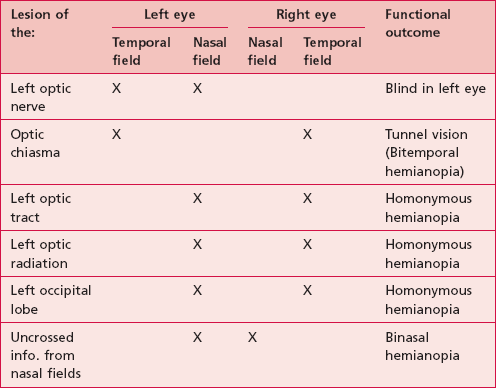

The input from central and peripheral visual fields (S2.10) is important in providing a complete picture of the external environment. Therefore any lesion involving the visual pathway could result in incomplete input, which may hinder functional ability. The presentation of lesions at different points along the visual pathway is shown in Table 27.1.

Fixing and scanning

Visual acuity requires coordination between head and body movements to allow the visual stimuli to be picked up by the appropriate part of the retina. This is achieved via fixing (S2.10) and scanning (S2.10). A deficit affecting these abilities may produce poor balance and inaccurate movement during function.

Why do I need to assess these aspects of vision?

Visual deficits are present in as many as 40% of patients with cerebrovascular accidents and 50% of traumatic brain injuries (Kerty 2005). Vision is important in the context of balance and movement and therefore any deficit may have a profound effect on the patient’s ability to function.

How do I assess these aspects of vision?

Visual fields

Therapist

1. Use a long object (such as a ruler) for testing to avoid arms being seen when reaching around in front of the patient’s face.

2. The therapist should stand behind the patient. In addition it is preferable to have an assistant sitting in front of the patient to provide a visual target on which the patient can focus and from where compliance to the protocol can be evaluated.

3. Ask the patient to keep looking straight ahead at all times.

4. Ask the patient to verbalize or raise a hand when they see any change in their visual environment.

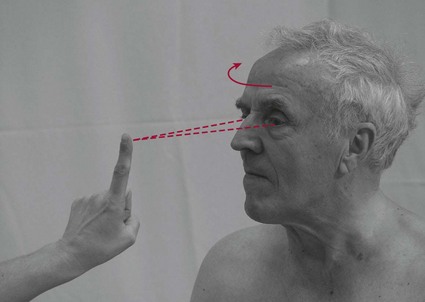

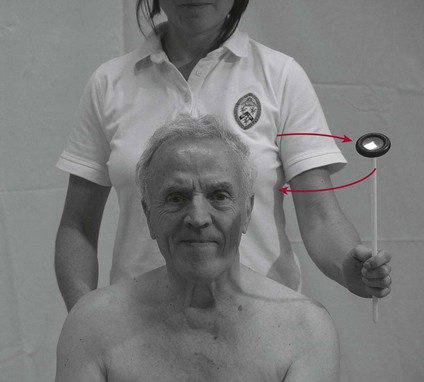

5. The therapist then starts to move the ruler from behind the patient’s head in an arc towards the front of the patient’s face, keeping it equidistant from the patient (Fig. 27.1).

Figure 27.1 Testing visual fields.

6. If the patient acknowledges the stimuli the therapist may decide to confirm the observation by randomly keeping the ruler still and then moving it a small distance backwards and forwards. Ask the patient to report whether the ruler is still or moving.

7. Return to the start position.

8. To give a complete picture, this arc-like movement needs to be repeated for left and right sides and for upper and lower quadrants.

9. The therapist should mix up the order of testing so that the patient is unable to predict the stimuli.

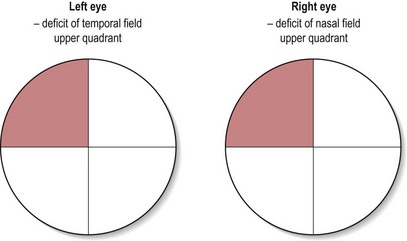

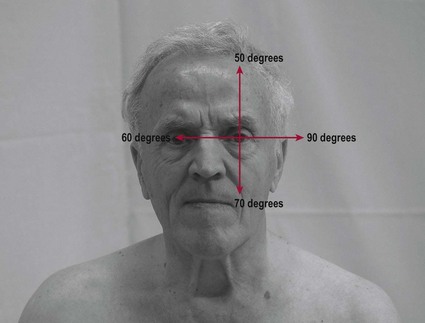

Are all visual fields intact? No, there may be a deficit of the visual pathway. The normal range of the visual fields for one eye is 60° medially, 90° laterally, 50° superiorly and 70° inferiorly (Fig. 27.2). The pattern of any deficit may help diagnose the location of the lesion (Table 27.1). If this deficit is not being managed referral back to the medical team is required.

Figure 27.2 Extremes of unilateral visual field.

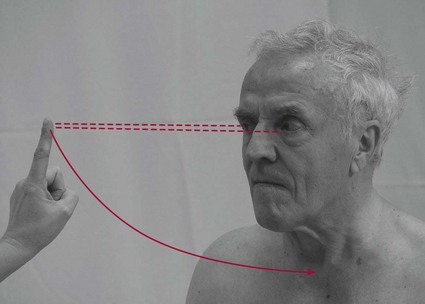

Fixing (Fig. 27.3)

Therapist

1. The therapist should sit 3–6 feet in front of the patient, facing them.

2. The therapist holds their finger up in front of the patient’s face, about 2 feet away from their nose.

3. Keep the finger still, the patient is requested to keep their eyes on the finger while turning their head towards the right.

4. Ask them to return to the centre and then repeat to the left.

Scanning (Fig. 27.4)

Therapist

1. The therapist should sit 3–6 feet in front of the patient, facing them.

2. The therapist holds their finger up in front of the patient’s face.

3. The patient should keep their head facing the therapist and completely still throughout the procedure.

4. The therapist then moves their finger laterally and asks the patient to follow the course of their finger with their eyes only. Ask them to follow your finger back to the centre.

5. The therapist then needs to repeat the assessment in all six cardinal directions or in an ‘H’ pattern.

Are they able to scan throughout the range? If not, there may be a deficit of the cranial nerves III, IV or VI.

Is there any oscillation of the eye during the upward and lateral gaze? This could be nystagmus. This represents an incoordination of the muscles controlling the eye movements. It is often associated with ataxia (S3.26) and indicative of a cerebellum lesion.