Chapter 25 Viral Pneumonia

Burden of Disease

Viral Community-Acquired Pneumonia

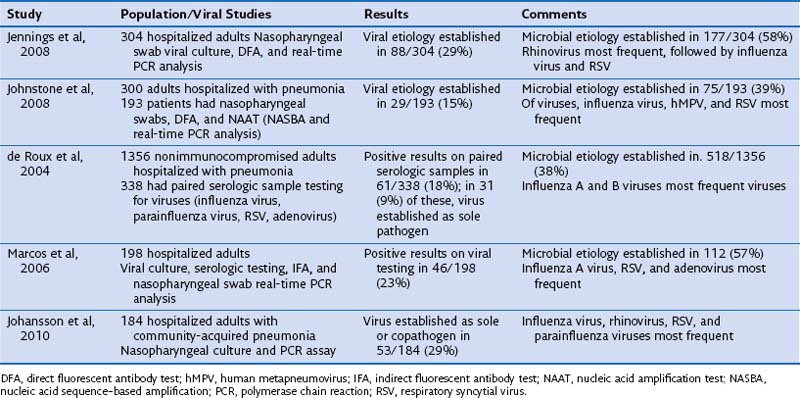

The proportion of pneumonias in adults that are caused by viruses is difficult to quantify with any precision. This lack of certainty is not surprising, because in approximately 50% of pneumonias, an identifiable pathogen cannot be established by conventional laboratory testing. Molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis improve this number but are rarely performed in routine clinical care. Difficulties in obtaining adequate specimens for viral cultures or molecular testing add to the problem. However, several recent studies have made efforts to quantify the burden of viral community-acquired pneumonias in adults and are summarized in Table 25-1. Although the proportion of viral pneumonias varies in these studies owing to differences in study populations and rigor of testing for viruses, it is clear that viruses cause a significant proportion of pneumonias. Overall, in immunocompetent adults hospitalized with pneumonia, viruses are the responsible pathogens in 15% to 30% of the cases, either by themselves or as copathogens with bacteria. Lower respiratory secretions such as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid, tracheal aspirates, or good-quality induced sputum are preferable as specimens for diagnosis of viral pneumonia. Such specimens are more difficult to obtain, however, and most studies have used nasopharyngeal wash samples or swabs for culture and molecular testing. Presence of established pathogens such as influenza virus in such upper respiratory tract samples in a patient with pneumonia most probably implies that the virus is a sole or copathogen in causation of pneumonia; however, this general rule may not be applicable to other viruses. Presence of such viruses as rhinovirus might imply only upper respiratory infection in a patient with pneumonia due to another pathogen. Findings on studies of viral pneumonias must therefore be interpreted with some caution.

Viral Pneumonia in Immunocompromised Patients

Patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or solid organ transplantation or who are undergoing intensive chemotherapy for leukemias exhibit a higher incidence of viral upper respiratory infections than that in normal control subjects, as well as more frequent involvement of the lower respiratory tract, more severe pneumonias, and higher rates of death from viral pneumonia. All of the pathogens mentioned in Table 25-1 are represented in these patients. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), adenovirus, and parainfluenza virus, which usually cause only mild illness in immunocompetent persons, can cause severe pneumonias with high mortality rates in this high-risk patient population. Extrapulmonary manifestations of influenza infection, such as myocarditis, are not unusual in this population. RSV is the most common viral pathogen of the lower respiratory tract in patients who have undergone hematopoietic stem cell or solid organ transplantation, as reported in many series. Fulminant, disseminated adenoviral infections have been reported in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is a major problem in stem cell and solid organ transplant recipients and probably is the most common viral pneumonia among patients who are not on prophylaxis or preemptive treatment regimens.

Pathogens

Influenza Viruses

Diagnosis

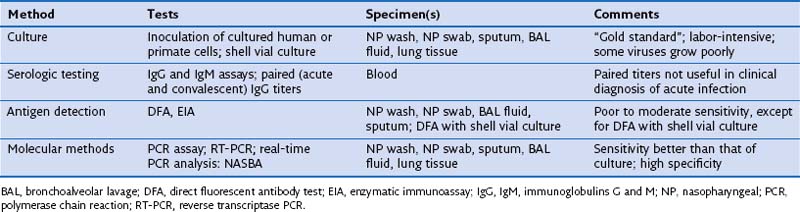

A variety of clinical specimens are suitable for diagnosis of viral pneumonia. These include, in order of preference, lung tissue and BAL fluid, nasopharyngeal wash sample, nasopharyngeal swabs, and sputum. BAL often is avoided because of its invasive nature but nevertheless is desirable in immunocompromised and critically ill patients, in whom a specific diagnosis is necessary and co-infections are common. Diagnosis of viral infection in a patient with pneumonia can be attempted by one or more of four methods, as summarized in Table 25-2.

Treatment

Zanamivir is an alternative to oseltamivir. It is available only as an inhalant. Zanamivir can provoke wheezing and clog nebulizers (the CDC advises against using this agent in a nebulizer) and probably should be avoided in patients with respiratory compromise. Increasing resistance to oseltamivir is being reported in influenza A virus. These strains remain sensitive to zanamivir and peramivir. Oseltamivir is less active against influenza B virus than against influenza A virus; zanamivir is preferred if influenza B virus is known to be the etiologic agent, in the absence of contraindications to its use. The incidence of resistance to oseltamivir in the United States remains low, as reported by the CDC (less than 1% for H1N1 and H3N2) in April 2011 (http://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Bacterial coinfections in lung tissue specimens from fatal cases of 2009 pandemic influenza A (H1N1)—United States, May-August 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1071–1074.

Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, et al. Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1708–1719.

Falsey AR, Walsh EE. Viral pneumonia in older adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:518–524.

Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1749–1759.

Hall CB. Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1917–1928.

Johansson N, Kalin M, Tiveljung-Lindell A, et al. Etiology of community-acquired pneumonia: increased microbiological yield with new diagnostic methods. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:202–209.

Louria DB, Blumenfeld HL, Ellis JT, et al. Studies on influenza in the pandemic of 1957–1958. II. Pulmonary complications of influenza. J Clin Invest. 1959;38:213–265.

Mahony JB. Detection of respiratory viruses by molecular methods. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21:716–747.

McGeer A, Green KA, Plevneshi A, et al. Antiviral therapy and outcomes of influenza requiring hospitalization in Ontario, Canada. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1568–1575.

Perez-Padilla R, de la Rosa-Zamboni D, Ponce de Leon S, et al. Pneumonia and respiratory failure from swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:680–689.

Rello J, Pop-Vicas A. Clinical review: primary influenza viral pneumonia. Crit Care. 2009;13:235.

Shah JN, Chemaly RF. Management of RSV infections in adult recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:2755–2763.