CHAPTER 92 VIRAL MENINGITIS AND ENCEPHALITIS

Acute viral infections of the central nervous system (CNS) are normally classified into two clinical syndromes, meningitis and encephalitis, which reflects the anatomical localization of the infection. They are inflammatory conditions of the leptomeninges and brain, respectively. In general, both are caused by the same viral agents, although there is often a propensity for an agent to be more associated with one condition than with the other. Many of these infections are related to neuroinvasion during the course a systemic infection (e.g., arbovirus and enterovirus infections), and only a small subset of patients with the infection actually develops either meningitis or encephalitis. In contrast, rabies virus produces encephalomyelitis and does not cause systemic infection.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Viral Meningitis

The incidence of aseptic meningitis has been estimated at 10.9 per 100,000 people per year.1 Viral meningitis is more common in men and boys, with a male-to-female ratio of at least 1.5. For reasons that are unclear, the disease is relatively uncommon among people older than 40. There is a striking seasonal incidence, with peak incidence during the months of July, August, and September, which reflects the dissemination of both enteroviruses and arboviruses (see the following sections).

Specific Viral Etiologies

Enteroviruses are ubiquitous, infect individuals of all ages, and cause a wide spectrum of clinical illnesses. Humans are infected by multiple enteroviruses during their lifetime. There is a predominance of enterovirus infections during the summer and fall, although sporadic cases occur all year. Enteroviruses belong to the family Picornaviridae and include the polioviruses, coxsackieviruses, echoviruses, and the numbered human enteroviruses 68 to 71. The enteroviruses are the most common cause of viral meningitis and are responsible for more than 80% of cases in which a specific etiology can be identified.2 Less commonly, enteroviruses cause encephalitis. The enteroviruses replicate in the gastrointestinal tract and are transmitted via the fecal-oral route. Most enteroviral infections are asymptomatic, and gastrointestinal symptoms are usually absent. Recognized cases of viral meningitis represent only a small fraction of enteroviral infections.3 Patients with agammaglobulinemia may develop chronic enterovirus meningitis, and therapy with intravenous immunoglobulin has proved useful in these patients.4,5

Mumps virus was at one time responsible for more cases of viral meningitis than any other single virus. Mumps virus is transmitted via the respiratory route. Outbreaks of mumps peak in the late winter and early spring in northern temperate climates, and major outbreaks traditionally occur at intervals of 2 to 7 years. Mumps virus infection confers lifelong immunity. Mumps virus infection may be associated with parotiditis, orchitis, and deafness. In mumps meningitis, mumps virus may frequently be isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Mumps meningitis has become much less common in the United States since the introduction of live attenuated mumps vaccine in the late 1960s. The Jeryl-Lynn strain of mumps vaccine, which is in trivalent vaccines currently used in the United States, has not been associated with neurological complications. However, the Urabe strain of mumps vaccine, which has been used in other countries, is associated with occasional cases of meningitis.6

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus is an arenavirus that causes inapparent infection in rodents and is present in their excreta, and direct contact may result in human infection. In humans, a biphasic illness is common: a mild systemic illness with fever, malaise, and myalgias that improves before the onset of meningitis. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis infection may be associated with severe respiratory symptoms, with pulmonary infiltrates, parotitis, orchitis, or rash.7 Although most cases of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection manifest with meningitis, encephalitis may also occur.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2 is associated with viral meningitis, particularly at the time of an initial episode of genital herpes infection and especially in girls and women. Meningitis may be preceded by genital or pelvic pain. A minority of these patients go on to have recurrent episodes of meningitis, which may meet the criteria for Mollaret’s meningitis, in which the virus usually cannot be cultured from CSF, but HSV type 2 (occasionally type 1) DNA can often be detected in CSF with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification.8,9

With regard to other viruses, viral meningitis is associated with primary infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in 5% to 10% of patients, which usually occurs just before the time of seroconversion. Cranial nerve palsies, particularly involving cranial nerves V, VII, and VIII, are more common in HIV meningitis than in viral meningitis with other causes.10 Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) may produce meningitis associated with chickenpox or shingles and rash may not be associated.11,12 PCR amplification is useful in the diagnosis of varicella-zoster virus CNS infections.

Viral Encephalitis

Although many of the same viruses cause viral meningitis and encephalitis, the relative frequencies of the two conditions are different. The incidence of encephalitis has been estimated at 7.4 per 100,000 people per year.1 More than 100 viruses are known to cause acute viral encephalitis, and specific etiological viral agents vary in frequency from year to year13 (Table 92-1). After thorough investigation, one study demonstrated a confirmed or probable viral agent in only 9% of cases of encephalitis, which included those with nonviral causes.14

TABLE 92-1 Significant Causes of Viral Encephalitis in the United States

Adapted from Griffin DE, Inouye RT: Acute viral encephalitis. In Schlossberg D, ed: Current Therapy of Infectious Disease, 2nd ed. St. Louis: Mosby, 2001, pp 270-276.

Specific Viral Etiologies

HSV type 1 is the most common cause of sporadic encephalitis and herpes simplex encephalitis has been identified in about 5% to 10% of cases of acute viral encephalitis in the United States15 with an estimated incidence of about 1 per 250,000 to 500,000 people per year.16 There is no seasonal preponderance or gender predilection. There is a bimodal age distribution in which about one third of cases occur in patients younger than 20 and one half in patients older than 50; this may reflect the occurrence of primary infections in younger individuals and reactivation of latent infections in older patients.17,18 About 90% of cases of herpes simplex encephalitis are caused by HSV type 1, and 10%are caused by HSV type 2.19 Familial herpes simplex encephalitis has been reported infrequently.20

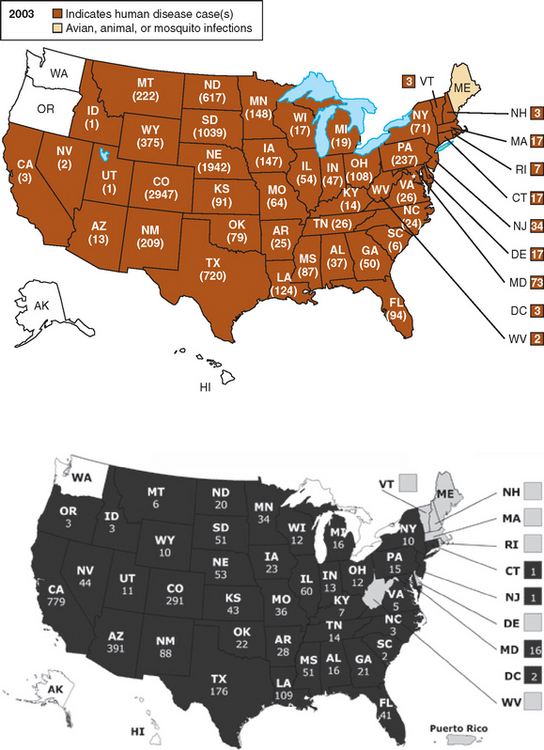

Arboviral infections have a seasonal (usually in the summer and early fall) and geographical distribution that depends on complex ecological cycles between arthropod vectors (mosquitoes and ticks) and their natural hosts. The arboviruses are a biological classification of viruses based on transmission by hematophagous arthropod vectors, and they include viruses in different families, including togaviruses, flaviviruses, bunyaviruses, and reoviruses. Most arboviral infections produce a subclinical or mild clinical illness and go undiagnosed. A minority of patients develop a febrile illness, and a much smaller minority develop encephalitis or, less commonly, meningitis. Epidemics of eastern equine encephalitis are relatively small, with fewer than 35 human cases, and they usually occur in the coastal regions of the eastern United States. Western equine encephalitis occurs in the western United States and in Canada. Venezuelan equine encephalitis has occurred in large outbreaks in Central and South America, and in 1971, a large epidemic in Mexico crossed the Texas border.21 In Venezuelan equine encephalitis, horses are important amplifying hosts, whereas in eastern and western equine encephalitis, horses, like humans, are dead-end hosts. St. Louis encephalitis occurs in both urban and rural outbreaks, and it is an important cause of epidemic encephalitis in North America. In 1975, an epidemic of St. Louis encephalitis included cases in 30 states and in Canada.22 About 25 sporadic cases of Powassan encephalitis have occurred in the northern United States and Canada (Ontario and Quebec).23,24 Powassan virus is transmitted by Ixodes ticks. Most cases of California serogroup encephalitis are caused by La Crosse virus and occur in the central United States. Japanese encephalitis is the most common cause of epidemic encephalitis in the world. Large summer epidemics and endemic disease in Asia are responsible for an estimated 50,000 cases and 15,000 deaths annually.25 Japanese encephalitis virus is transmitted by the mosquito Culex tritaeniorhychnus that breeds in rice fields. Water birds are natural hosts, and pigs may be important amplifying hosts in many countries. In 1999, West Nile virus was responsible for an outbreak of encephalitis in New York City and neighboring counties. The mechanism of introduction of the virus into North America is unknown. The virus has quickly moved across the North American continent. In the United States during 2003, there were 2866 cases of West Nile virus infection causing meningitis or encephalitis and 264 deaths26 (Fig. 92-1). Elderly and immunosuppressed patients are particularly at risk for disease and a fatal outcome. Transmission of West Nile virus may also occur by organ transplantation, infected blood products, and breast milk.

Figure 92-1 Distribution of human cases of West Nile virus infection by state in the United States during 2003 and 2004.

(From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnilel)

Nipah virus was associated with an epidemic of encephalitis in pig farmers and abattoir workers in Malaysia in 1998 and 1999, which affected 265 people and killed 105.27 Two species of large fruit bats (flying foxes) are the natural hosts of the virus.28 Infected pigs developed respiratory disease and transmitted the virus to humans via the respiratory route, but subsequent outbreaks of Nipah virus encephalitis in Bangladesh and India have not been traced to pig infections.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND INVESTIGATIONS

The diagnosis of viral meningitis or encephalitis can often be made on the basis of the clinical evaluation without specific laboratory or imaging investigations. Patients with viral meningitis have fever, headache, and neck stiffness and rigidity. There is an inflammatory response involving proinflammatory cytokines that play a role in producing fever. The leptomeninges are pain-sensitive structures that account for headache and neck pain and stiffness. Patients may have mild drowsiness, but the level of consciousness is not severely altered, and there are no seizures, focal neurological signs, or other clinical evidence of involvement of the brain parenchyma. In contrast, patients with viral encephalitis have one or more of these features. Some patients with encephalitis have prominent focal features, including hemiparesis or aphasia, whereas others have diffuse brain involvement with depression in the level of consciousness without lateralizing signs. Specific arboviruses are associated with regional involvement of the CNS, including the basal ganglia with Japanese encephalitis virus, the rhombencephalon with West Nile virus, and the spinal cord with tickborne encephalitis virus and West Nile virus.

Examination of the CSF is the mainstay of diagnosis in viral meningitis and encephalitis. In viral meningitis, there is typically mild mononuclear pleocytosis, a normal or mildly elevated protein concentration, and a normal or mildly decreased glucose concentration. In meningitis arising from mumps and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infections, the CSF cell counts may be in the thousands. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes may predominate in the CSF, particularly early in the illness. In this case, a repeat examination several hours later usually shows a shift to mononuclear cells.29 Viruses may be cultured from the CSF, or nucleic acids may be detected with PCR amplification techniques. Serological testing may also be helpful for making a specific etiological diagnosis in viral meningitis. Patients with encephalitis should also undergo brain imaging, preferably magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and CSF examination if there is no concern about brain herniation or other contraindications to lumbar puncture.

Specific Clinical Syndromes

Enteroviral meningitis manifests with fever, headache, and nuchal rigidity, and nausea, vomiting, and photophobia are common. Young children or neonates may exhibit irritability and nonspecific findings. Exanthemata, hand-foot-and-mouth disease, herpangina, pleurodynia, myocarditis, pericarditis, and hemorrhagic conjunctivitis are associated with enterovirus infections. The duration of illness is usually about 1 week, but some symptoms may persist for several weeks, particularly in adults. Serological testing is of only very limited value in enteroviral meningitis because of the large number of enteroviral serotypes. Enteroviruses may be cultured from the oropharynx and stool and also in blood, CSF, urine, and tissues. However, viral growth in culture may take 4 to 8 days, and some enterovirus serotypes grow poorly.30 PCR amplification on CSF for enteroviruses has proved diagnostically superior to viral cultures and has an important effect in reducing the use of antibiotics and in shortening hospitalizations.31 Enteroviruses can also cause encephalitis. In 1998 there was an enterovirus 71 epidemic in Taiwan with many cases of rhombencephalitis.32

Epstein-Barr virus meningitis may occur with or without an infectious mononucleosis syndrome, and meningitis is the most common neurological manifestation of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Encephalitis is less common, and its prognosis is fairly good. Atypical lymphocytes may be present in peripheral blood specimens or in CSF. Epstein-Barr virus is rarely cultured from CSF. PCR amplification may reveal Epstein-Barr virus DNA in the CSF, but the sensitivity and specificity of the test have not yet been determined.33 Serological tests may show evidence of acute Epstein-Barr virus infection with immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody to viral capsid antigen or with antibody to the diffuse component of the early antigen in association with the absence of antibody to nuclear antigen.34

Herpes simplex encephalitis is characterized by headache, fever, and alteration of consciousness, which may develop over a period of hours or more slowly, over days. Headache is usually a prominent early symptom, and fever is almost always present. Focal neurological features are frequently present, including aphasia, hemiparesis, and visual field defects (superior quadrant). Focal or generalized seizures and olfactory or gustatory hallucinations may occur as well. Behavioral disturbances (sometimes bizarre), personality changes, or psychotic features may occur and be prominent, and psychiatric disease is sometimes suspected. Signs of autonomic dysfunction are also often present. Papilledema is present in a minority of patients. Mild or atypical forms of herpes simplex encephalitis have been recognized without focal features, and they have been associated with both HSV types 1 and 2 infections, immunosuppression with corticosteroids or coexisting HIV infection, or disease predominantly involving the nondominant temporal lobe.35,36 Herpes simplex encephalitis may occur with unusual clinical features, including the anterior opercular syndrome.37

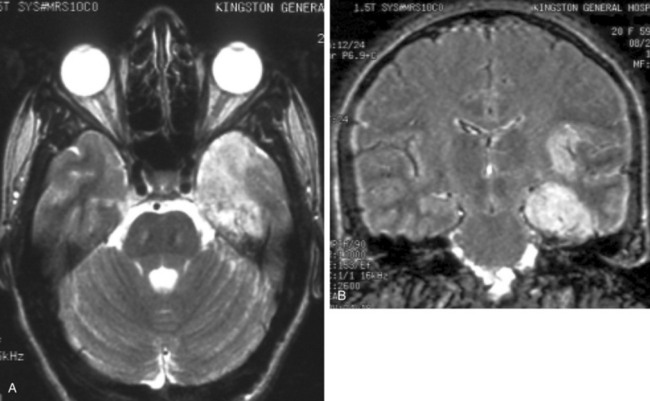

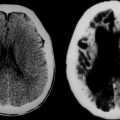

Focal electroencephalographic abnormalities are present in about 80% of cases of herpes simplex encephalitis.38 Sharp- and slow-wave activity is usually localized to the temporal region, and periodic complexes may be present.39 Brain imaging studies, particularly MRI, usually reveal abnormalities in involved areas, including the frontal and temporal lobes, although rare patients with normal MRI studies have been reported.40 Computed tomography reveals hypodense lesions in the temporal lobe and orbitofrontal region, which may demonstrate mass effect, regions of hemorrhage, and irregular contrast enhancement. On MRI, hyperintense signal intensities are typically seen on T2-weighted images in typical sites (Fig. 92-2A), including one or both inferomedial temporal lobes, insular cortex, inferior frontal lobes, cingulate gyrus, and thalamus, with foci of hemorrhage caused by the presence of degradation products of hemoglobin, whereas T1-weighted images show hypointense signal in the same areas, and meningeal enhancement may be demonstrated after administration of gadolinium.41 Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery imaging sequences demonstrate superior definition of temporal lobe abnormalities in comparison with standard T1- and T2-weighted images36 (see Fig. 92-2B). Diffusion MRI studies may also be useful for early detection of lesions.42,43

A lumbar puncture may reveal an elevated opening pressure. CSF examination usually demonstrates a mononuclear cell pleocytosis with mildly elevated protein and normal glucose levels. Pleocytosis is present is about 97% of cases,38 but it may be absent in either immunocompetent44 or immunosuppressed45,46 patients. Leukocyte counts exceeding 500 cells/μL are found in fewer than 10% of patients. Erythrocytes in the CSF in a nontraumatic lumbar puncture are present with similar frequency in patients with encephalitis of other causes.38 HSV can be cultured from CSF in only about 4% of cases.47 A number of reports have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity of PCR amplification assays for the detection of HSV DNA in the CSF of patients with suspected herpes simplex encephalitis. Primers from a HSV sequence that is common to both HSV types 1 and 2 (either the glycoprotein or HSV DNA polymerase) identify HSV DNA in the CSF.48 CSF specimens from patients with brain biopsy–proved herpes simplex encephalitis and from those with other proved diseases have a diagnostic sensitivity of 98% at the time of clinical presentation, as well as a specificity that approaches 100%.49 False-negative results may occur when there is contamination of CSF by medical or laboratory staff or by the presence of inhibitors. Inhibitory activity for the Taq polymerase used in PCR amplification can be assessed by assays after “spiking” CSF specimens with multiple copies of HSV DNA.49 Inhibitory activity may result from porphyrin compounds from degradation of hemoglobin, or it may be present without any evidence of hemolysis of erythrocytes in the CSF.50,51 The specificity of positive PCR assays can be confirmed with restriction enzyme analysis, hybridization, and sequencing; false-positive results may be a problem in some laboratories.52 If a PCR assay for HSV DNA yields negative results on the first or second day of illness, it should, if clinical suspicion is high, be repeated because results that are initially negative may be followed by positive results on testing of a subsequent CSF specimen.53 The CSF remains positive for HSV DNA by PCR in more than 80% of patients at the end of one week of antiviral therapy.49 Before the development of PCR technology and widespread use of MRI, brain biopsy was an important diagnostic test for herpes simplex encephalitis. The utility of diagnostic brain biopsy for the management of encephalitis is currently controversial, especially in view of empirical antiviral drugs and rivaling sensitivity and specificity of PCR-based assays. At present, diagnostic brain biopsy is normally reserved for only a minority of cases of undiagnosed encephalitis that fail to respond to initial therapy.

Arboviral encephalitis occurs in a minority of patients with arboviral infections, and the majority of patients have inapparent infections or mild nonspecific illnesses. Meningitis is less common than encephalitis. Focal signs are occasionally prominent in arboviral encephalitis. Patients may also have evidence of spinal cord involvement.54,55 Muscle weakness has been noted in patients with West Nile encephalitis, and ventilatory support may be required.56,57 Many cases with muscle weakness have ventral horn cell involvement as a result of the viral infection,55 and rare patients have features of an atypical Guillain-Barré syndrome.58 Movement disorders may occur in Japanese encephalitis59 and West Nile encephalitis.60 Seizures and raised intracranial pressure may be common causes of death.61 Clinical illness usually develops with arboviral infections a few days after transmission of the arbovirus from a mosquito or tick vector. There is a wide range in the severity of encephalitides caused by arboviruses, from mild to severe and fatal. The frequency and severity of neurological sequelae are also variable. Certain arboviruses typically cause more severe disease and higher fatality rates than do others. For example, eastern equine encephalitis virus causes a severe encephalitis with a mortality rate of about 70%. In contrast, La Crosse virus causes a relatively mild encephalitis (California serogroup encephalitis) with a low fatality rate. Arboviruses may cause disease in certain age groups. Encephalitis caused by La Crosse virus usually occurs in children, although infection can occur at any age. Adults in epidemic areas seldom develop Japanese encephalitis because they have developed immunity from childhood infection. Infants often have severe sequelae from western equine encephalitis,62 and elderly patients are more likely to have more severe disease in St. Louis encephalitis63 and West Nile encephalitis. In West Nile encephalitis, there is an associated broad spectrum of neurological involvement, including meningitis, cerebellar disorder, myelitis, and parkinsonism and other movement disorders.60

Computed tomography or MRI scans have demonstrated lesions in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem in eastern equine encephalitis.64 MRI scans in Japanese encephalitis show lesions in the thalami in most patients and also lesions in the basal ganglia, midbrain and pons, cerebral cortex, and cerebellum.65,66 MRI lesions may be present in the thalamus, basal ganglia, and brainstem in tickborne encephalitis.67 A minority of patients with West Nile encephalitis have MRI abnormalities, and these often involve the basal ganglia, thalamus, and brainstem.60 There is usually pleocytosis with a modest number of leukocytes that are predominantly mononuclear cells. CSF protein levels are often elevated, but the CSF glucose level is usually normal. Viral cultures on CSF for arboviruses usually yield negative results, although Japanese encephalitis virus may be isolated from CSF in up to one third of patients.68 Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, tickborne encephalitis viruses, and Colorado tick fever virus may be isolated from blood.69,70 Arboviruses may be cultured from the brain and spinal cord in fatal cases. In rare cases, a diagnosis may be made by using brain biopsy.71 Most arboviral infections are diagnosed serologically. A serological diagnosis is commonly made on the basis of a fourfold or greater rise (or fall) in the titer of viral antibodies (immunofluorescent, hemagglutination inhibition, complement fixation, or neutralizing) during the infection. Both acute and convalescent sera should be obtained, the latter 2 to 6 weeks after the first. Serological cross-reactions can occur in areas where closely related viruses (e.g., flaviviruses) circulate or when patients have been vaccinated against a closely related virus.28 This problem can be resolved by parallel serological testing against the closely related viruses or by further assessment at a specialized laboratory with plaque reduction neutralization assays. The presence of viral specific serum IgM indicates primary infection, although IgM may remain present for many weeks. A diagnosis may be made at the time of admission to the hospital or soon afterward by demonstration of virus-specific IgM in the CSF by capture enzyme immunoassay.72,73 About one half of patients with West Nile encephalitis have IgM in CSF on admission to the hospital, and the majority develop IgM by the seventh day of admission; patients who do not develop IgM are more likely to have West Nile virus isolated and are more likely to die of the illness.74 Assays with PCR amplification may be useful in detecting viral RNA from arboviruses in CSF or brain tissues.75–77 In West Nile encephalitis, real-time PCR, the most sensitive of PCR techniques, is positive in only about one half of cases.74

Nipah virus encephalitis in Malaysia was characterized by fever, altered mental status, segmental myoclonus, seizures, cerebellar ataxia, and brainstem and cervical spinal cord signs, and there was a high mortality rate.78 T2-weighted MRI revealed multiple small, hyperintense lesions in brain white matter.79 CSF demonstrated pleocytosis and elevated protein levels.78 Pathological studies revealed infection of endothelial cell and neurons and microinfarctions caused by small vessel vasculitis in both the gray and white matter.80,81

Rabies usually develops 1 to 3 months (or, rarely, a few days or more than a year) after exposure, which is most often from an animal bite. However, there may be no history of an animal bite, particularly in association with transmission from bats. Patients with rabies often have distinctive clinical features,82 but physicians must have a high index of suspicion. Prodromal symptoms, including fever, chills, malaise, fatigue, insomnia, anorexia, headache, anxiety, and irritability, may last for a few days. About one half of patients develop pain, paresthesias, or pruritus at or close to the bite site, which may reflect infection in dorsal root ganglia. About 80% of patients develop an encephalitic (also called furious) form of rabies, and 20% develop a paralytic form. In the encephalitic form, patients have episodes of generalized arousal or hyperexcitability, which are separated by lucid periods.83 They may have aggressive behavior, confusion, and hallucinations. Fever is common, and signs of autonomic dysfunction, including hypersalivation, sweating, and piloerection, may be present. Nuchal rigidity and seizures may occur. About one half of patients develop hydrophobia, a characteristic manifestation of rabies (Fig. 92-3). Patients may initially experience pain in the throat or have difficulty swallowing. On attempts to swallow, they experience contractions of the diaphragm and other inspiratory muscles, which last for about 5 to 15 seconds. Subsequently, the sight, sound, or even mention of water (or of any liquids) may trigger the spasms. A draft of air on the skin may have the same effect (aerophobia). The disease may progress through paralysis, coma, and multiple organ failure, and eventually it causes death. In paralytic rabies, flaccid muscle weakness develops early in the course of the disease, and patients may survive longer.

Computed tomographic scans of the head are usually normal in rabies. There has been limited experience with MRI, although both normal features84 and increased signals on T2-weighted images in the medulla and pons85 have been observed. CSF analysis often yields abnormal findings. Anderson and colleagues found pleocytosis in 59% of cases during the first week of illness and in 87% after the first week.86 Mononuclear cells predominate in the CSF, the protein level may be mildly elevated, and the glucose level is usually normal. Serum neutralizing antibodies against rabies virus are not usually present in unimmunized patients until after the 10th day of illness,87 and death may occur without their development. Early in the illness, rabies virus is occasionally isolated from the saliva or CSF.86 A skin biopsy may confirm a diagnosis of rabies while the patient is alive.88 Rabies virus antigen may be detected in skin biopsies with the fluorescent antibody technique. Antigen may be demonstrated in small nerves of skin taken from the nape of the neck, which is rich in hair follicles. Detection of antigen in corneal impression smears is less sensitive than in skin biopsies.88 Diagnosis of rabies with brain biopsies has not been adequately evaluated. Postmortem CNS tissues can be assessed for rabies virus antigen and viral isolation. Rabies virus RNA has been demonstrated from brain tissues, saliva, and CSF with PCR amplification.89,90

Postinfectious encephalitis frequently affects children and young adults. The encephalitis usually follows a viral infection, including exanthematous agents (measles, rubella, vaccinia, varicella-zoster), nonspecific upper respiratory tract infections, and other nonviral infections.91 The illness is similar to that seen in neuroparalytic complications after a variety of immunizations, including rabies (e.g., Semple vaccine) and smallpox. Postinfectious encephalitis normally has a monophasic clinical course. The clinical features develop over a period of a few days and include mental status changes, seizures, and corticospinal tract, cerebellar, and brainstem signs, and fever may be present. MRI of the brain typically reveals multiple large, asymmetrical, T2-hyperintense lesions in the white matter, which may exhibit mass effect and contrast enhancement. CSF analysis often reveals mild mononuclear pleocytosis with elevated protein levels, but CSF may be normal; oligoclonal bands are usually absent.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

Viruses produce inflammation in the leptomeninges and in the brain parenchyma in viral meningitis and encephalitis, respectively. Viruses usually gain access to the CNS by either a hematogenous or neuronal route of spread. Hematogenous spread is more common. With replication in systemic tissues—for example, in lymphatic tissues or in muscle—a transient viremia develops, and virus spreads to the brain. Viruses may replicate in brain capillary endothelial cells, or there may be passive transfer of virus across the endothelium or via pinocytotic vesicles in epithelial cells of the choroid plexus with seeding of virus into CSF.13

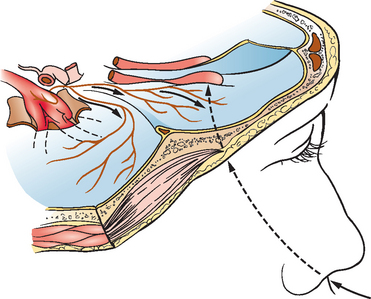

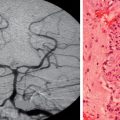

HSV and rabies virus spread within axons of peripheral nerves and gain access to the CNS.92,93 The frontotemporal localization of herpes simplex encephalitis in adults is believed to relate to the route of viral entry of HSV into the brain94 (Fig. 92-4). Davis and Johnson hypothesized that reactivated HSV, which is often latent in trigeminal ganglia, may spread alongthe trigeminal nerve fibers in tentorial nerves that innervate the basal meninges of the anterior and middle fossae.95 It has also been postulated that HSV may enter the brain along an olfactory pathway and spread along the base of the brain,94 particularly during primary HSV infection. Rabies virus also spreads to the CNS along peripheral nerves after inoculation of virus in a bite exposure, and the virus may also take an olfactory pathway in laboratory accidents with inhalation of aerosolized rabies virus96,97 or in caves containing millions of bats.98 Once rabies virus invades the CNS, the virus rapidly disseminates within axons along neuroanatomical connections by fast axonal transport.

Postinfectious encephalomyelitis, or acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, is discussed in Chapter 79. It frequently affects children and young adults. This form of encephalitis usually follows a viral infection, including exanthematous agents and nonspecific respiratory tract infections.

TREATMENT

By definition, viral meningitis is a benign, self-limited condition, and there is only very limited experience with antiviral therapy. Pleconaril is an antiviral drug that interferes with enterovirus attachment and coating by binding to the viral capsid.30 In a multicenter trial, efficacy was not demonstrated in infants with enteroviral meningitis,99 although a preliminary study showed that therapy resulted in shortening of the period of symptoms in meningitis in older individuals.100 Because it is a self-limited condition, specific antiviral therapy is not required for HSV type 2 meningitis. However, oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir have been used, although there have not yet been clinical trials.

Therapy with intravenous acyclovir is of proven efficacy in herpes simplex encephalitis. The mortality rate in untreated herpes simplex encephalitis was 70% in the placebo group of an early clinical trial.101 A multicenter clinical trial showed a mortality rate of 28% (at 18 months) after a 10-day course of intravenous acyclovir.102 Age and level of consciousness at the time of initiation of therapy were found to be important determinants of neurological outcome; patients older than 30 years of age or either semicomatose or comatose at the time therapy was begun had much less favorable outcomes. Therapy with intravenous acyclovir should be initiated in most patients with suspected viral encephalitis and continued until the diagnosis is excluded or believed highly unlikely. Acyclovir, 10 mg/kg every 8 hours (30 mg/kg/day), is given and usually continued for 14 to 21 days; higher dosages in the range of 30 to 60 mg/kg/day have also been used. There is anecdotal evidence that shorter courses of therapy (e.g., 10 days) have been associated with a higher incidence of recurrent disease or relapse. The viral enzyme thymidine kinase activates the drug to produce acyclovir-5′-monophosphate, and host cell enzymes further phosphorylate this compound to form a triphosphate derivative, which inhibits viral DNA polymerase and acts as a viral chain terminator. Adjustments in the acyclovir dosage are necessary in patients with renal insufficiency. Oral therapy has not yet been evaluated in herpes simplex encephalitis. A multicenter clinical trail is currently in progress by the Collaborative Antiviral Study Group (Principal Investigator, Dr. Richard J. Whitley, University of Alabama at Birmingham) to assess the efficacy and safety of additional therapy with oral valacyclovir at a dose of 2g three times a day for 90 days versus placebo after conventional therapy with 14 to 21 days of intravenous acyclovir.

Cytomegalovirus encephalitis is normally a disease of immunocompromised individuals, especially patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Highly active antiretroviral therapy is effective in patients with HIV/AIDS to control cytomegalovirus infection and reduce the mortality rate associated with cytomegalovirus disease.103 Intravenous ganciclovir, intravenous foscarnet, or a combination of the two drugs is recommended for treatment of cytomegalovirus ventriculoencephalitis.104 Although this therapy may stabilize the neurological condition of the patient, it probably does not improve survival rates.103 Cytomegalovirus encephalitis is rare in immunocompetent patients, and treatment protocols have not been established.

There is no therapy of proven benefit for arboviral encephalitis, including West Nile encephalitis.105 A multicenter clinical trial by the Collaborative Antiviral Study Group evaluating an intravenous immunoglobulin preparation from Israel containing high-titer antibody against West Nile virus is now in progress, and there is also a randomized, unblinded clinical study in progress using interferon α-2b.106 With regard to therapy for Japanese encephalitis, a double-blind, placebocontrolled clinical trial in Vietnam failed to demonstrate a difference in mortality rates or functional outcome with intramuscular administration of interferon α-2a (10 million units/m2 body surface area daily for 7 days).106

For postinfectious encephalitis, there have been no clinical trials documenting benefit from any treatment, and spontaneous improvement occurs. Most studies have showed a temporal benefit of corticosteroids, although others have shown no difference in the clinical course or have revealed higher morbidity and mortality rates.107 Plasma exchange108 and intravenous immunoglobulin109 have also been reported to be associated with improvement in postinfectious encephalitis.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Booss J, Esiri MM. Viral Encephalitis in Humans. Washington, DC: ASM Press, 2003.

Johnson RT. Viral Infections of the Nervous System, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

Nathanson N, Ahmed R, Gonzalez-Scarano F, et al. Viral Pathogenesis. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1997.

Roos KL. Principles of Neurologic Infectious Diseases. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2005.

Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM. Infections of the Central Nervous System, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

1 Beghi E, Nicolosi A, Kurland LT, et al. Encephalitis and aseptic meningitis, Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1950–1981: I. Epidemiology. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:283-294.

2 Rotbart HA. Enteroviral infections of the central nervous system. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:971-981.

3 Torphy DE, Ray CG, Thompson RS, et al. An epidemic of aseptic meningitis due to echovirus type 30: epidemiologic features and clinical and laboratory findings. Am J Public Health. 1970;60:1447-1455.

4 McKinney RE, Katz SL, Wilfert CM. Chronic enteroviral meningoencephalitis in agammaglobulinemic patients. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:334-356.

5 Misbah SA, Spickett GP, Ryba PC, et al. Chronic enteroviral meningoencephalitis in agammaglobulinemia: case report and literature review. J Clin Immunol. 1992;12:266-270.

6 Miller E, Goldacre M, Pugh S, et al. Risk of aseptic meningitis after measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine in UK children. Lancet. 1993;341:979-982.

7 Lewis JM, Utz JP. Orchitis, parotitis and meningoencephalitis due to lymphocytic-choriomeningitis virus. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:776-780.

8 Tedder DG, Ashley R, Tyler KL, et al. Herpes simplex virus infection as a cause of benign recurrent lymphocytic meningitis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:334-338.

9 Kupila L, Vainionpaa R, Vuorinen T, et al. Recurrent lymphocytic meningitis: the role of herpesviruses. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:1553-1557.

10 Levy RM, Bredesen DE. Central nervous system dysfunction in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1988;1:41-64.

11 Johnson R, Milbourn PE. Central nervous system manifestations of chickenpox. CMAJ. 1970;102:831-834.

12 Jhaveri R, Sankar R, Yazdani S, et al. Varicella-zoster virus: an overlooked cause of aseptic meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:96-97.

13 Johnson RT. Viral Infections of the Nervous System. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1998.

14 Glaser CA, Gilliam S, Schnurr D, et al. In search of encephalitis etiologies: diagnostic challenges in the California Encephalitis Project, 1998–2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:731-742.

15 Centers for Disease Control. Encephalitis Surveillance Annual Summary 1978, Issued May 1981. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1981.

16 Whitley RJ, Lakeman F. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: therapeutic and diagnostic considerations. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:414-420.

17 Koskiniemi M, Piiparinen H, Mannonen L, et al. Herpes encephalitis is a disease of middle aged and elderly people: polymerase chain reaction for detection of herpes simplex virus in the CSF of 516 patients with encephalitis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;60:174-178.

18 Tyler KL. Herpes simplex virus infections of the central nervous system: encephalitis and meningitis, including Mollaret’s. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl 2):57A-64A.

19 Aurelius E, Johansson B, Skoldenberg B, et al. Encephalitis in immunocompetent patients due to herpes simplex virus type 1 or 2 as determined by type-specific polymerase chain reaction and antibody assays of cerebrospinal fluid. J Med Virol. 1993;3:179-186.

20 Jackson AC, Melanson M, Rossiter JP. Familial herpes simplex encephalitis [Letter]. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:406-407.

21 Ehrenkranz NJ, Ventura AK. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus infection in man. Annu Rev Med. 1974;25:9-14.

22 Luby JP. St. Louis encephalitis. Epidemiol Rev. 1979;1:55-73.

23 Artsob H. Powassan encephalitis. Monath TP, editor. The Arboviruses: Epidemiology and Ecology. vol 4. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1989:29-49.

24 Gholam BIA, Puksa S, Provias JP. Powassan encephalitis: a case report with neuropathology and literature review. CMAJ. 1999;161:1419-1422.

25 Solomon T. Recent advances in Japanese encephalitis. J Neurovirol. 2003;9:274-283.

26 Solomon T. Flavivirus encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:370-378.

27 Parashar UD, Sunn LM, Ong F, et al. Case-control study of risk factors for human infection with a new zoonotic paramyxovirus, Nipah virus, during a 1998–1999 outbreak of severe encephalitis in Malaysia. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1755-1759.

28 Chua KB, Koh CL, Hooi PS, et al. Isolation of Nipah virus from Malaysian Island flying-foxes. Microbes Infect. 2002;4:145-151.

29 Feigin RD, Shackelford PG. Value of repeat lumbar puncture in the differential diagnosis of meningitis. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:571-574.

30 Sawyer MH. Enterovirus infections: diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2001;13:65-69.

31 Ramers C, Billman G, Hartin M, et al. Impact of a diagnostic cerebrospinal fluid enterovirus polymerase chain reaction test on patient management. JAMA. 2000;283:2680-2685.

32 Huang CC, Liu CC, Chang YC, et al. Neurologic complications in children with enterovirus 71 infection. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:936-942.

33 Portegies P, Corssmit N. Epstein-Barr virus and the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13:301-304.

34 Gotlieb-Stematsky T, Arlazoroff A. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Klawans HL, et al, editors. Viral Disease. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1989:249-261.

35 Domingues RB, Tsanaclis AM, Pannuti CS, et al. Evaluation of the range of clinical presentations of herpes simplex encephalitis by using polymerase chain reaction assay of cerebrospinal fluid samples. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:86-91.

36 Fodor PA, Levin MJ, Weinberg A, et al. Atypical herpes simplex virus encephalitis diagnosed by PCR amplification of viral DNA from CSF. Neurology. 1998;51:554-559.

37 McGrath NM, Anderson NE, Hope JK, et al. Anterior opercular syndrome, caused by herpes simplex encephalitis. Neurology. 1997;49:494-497.

38 Whitley RJ, Soong SJ, Linneman C, et al. Herpes simplex encephalitis: clinical assessment. JAMA. 1982;247:317-320.

39 Ch’ien LT, Boehm RM, Robinson H, et al. Characteristic early electroencephalographic changes in herpes simplex encephalitis. Arch Neurol. 1977;34:361-364.

40 Domingues RB, Fink MC, Tsanaclis AM, et al. Diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by magnetic resonance imaging and polymerase chain reaction assay of cerebrospinal fluid. J Neurol Sci. 1998;157:148-153.

41 Demaerel P, Wilms G, Robberecht W, et al. MRI of herpes simplex encephalitis. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:490-493.

42 McCabe K, Tyler K, Tanabe J. Diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities as a clue to the diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis. Neurology. 2003;61:1015-1016.

43 Kuker W, Nagele T, Schmidt F, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI in herpes simplex encephalitis: a report of three cases. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:122-125.

44 Schlageter N, Jubelt B, Vick NA. Herpes simplex encephalitis without CSF leukocytosis. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:1007-1008.

45 Price R, Chernik NL, Horta-Barbosa L, et al. Herpes simplex encephalitis in an anergic patient. Am J Med. 1973;54:222-228.

46 Tan SV, Guiloff RJ, Scaravilli F, et al. Herpes simplex type 1 encephalitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1993;34:619-622.

47 Nahmias AJ, Whitley RJ, Visintine AN, et al. Herpes simplex virus encephalitis: laboratory evaluations and their diagnostic significance. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:829-836.

48 Whitley RJ, Kimberlin DW, Roizman B. Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:541-553.

49 Lakeman FD, Whitley RJ, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study Group. Diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis: application of polymerase chain reaction to cerebrospinal fluid from brain-biopsied patients and correlation with disease. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:857-863.

50 Aurelius E, Johansson B, Skoldenberg B, et al. Rapid diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by nested polymerase chain reaction assay of cerebrospinal fluid. Lancet. 1991;337:189-192.

51 Dennett C, Klapper PE, Cleator GM, et al. CSF pretreatment and the diagnosis of herpes encephalitis using the polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Meth. 1991;34:101-104.

52 Tyler KL. Positive CSF HSV PCR in patients with GBM: a note of caution [Letter]. Neurology. 2000;55:604.

53 Weil AA, Glaser CA, Amad Z, et al. Patients with suspected herpes simplex encephalitis: rethinking an initial negative polymerase chain reaction result. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1154-1157.

54 Misra UK, Kalita J. Anterior horn cells are also involved in Japanese encephalitis. Acta Neurol Scand. 1997;96:114-117.

55 Li J, Loeb JA, Shy ME, et al. Asymmetric flaccid paralysis: a neuromuscular presentation of West Nile virus infection. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:703-710.

56 Asnis DS, Conetta R, Teixeira AA, et al. The West Nile virus outbreak of 1999 in New York: the Flushing Hospital experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:413-418.

57 Nash D, Mostashari F, Fine A, et al. The outbreak of West Nile virus infection in the New York City area in 1999. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1807-1814.

58 Ahmed S, Libman R, Wesson K, et al. Guillain-Barré syndrome: an unusual presentation of West Nile virus infection. Neurology. 2000;55:144-146.

59 Murgod UA, Muthane UB, Ravi V, et al. Persistent movement disorders following Japanese encephalitis. Neurology. 2001;57:2313-2315.

60 Sejvar JJ, Haddad MB, Tierney BC, et al. Neurologic manifestations and outcome of West Nile virus infection. JAMA. 2003;290:511-515.

61 Solomon T, Dung NM, Kneen R, et al. Seizures and raised intracranial pressure in Vietnamese patients with Japanese encephalitis. Brain. 2002;125:1084-1093.

62 Earnest MP, Goolishian HA, Calverley JR, et al. Neurologic, intellectual, and psychologic sequelae following western encephalitis: a follow-up study of 35 cases. Neurology. 1971;21:969-974.

63 Finley KH, Riggs N. Convalescence and sequelae. In: Monath TP, editor. St. Louis Encephalitis. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 1980:535-550.

64 Deresiewicz RL, Thaler SJ, Hsu L, et al. Clinical and neuroradiographic manifestations of eastern equine encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1867-1874.

65 Kumar S, Misra UK, Kalita J, et al. MRI in Japanese encephalitis. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:180-184.

66 Kalita J, Misra UK. Comparison of CT scan and MRI findings in the diagnosis of Japanese encephalitis. J Neurol Sci. 2000;174:3-8.

67 Marjelund S, Tikkakoski T, Tuisku S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings and outcome in severe tickborne encephalitis. Report of four cases and review of the literature. Acta Radiol. 2004;45:88-94.

68 Lowry PW. Arbovirus encephalitis in the United States and Asia. J Lab Clin Med. 1997;129:405-411.

69 Goodpasture HC, Poland JD, Francy DB, et al. Colorado tick fever: clinical, epidemiologic, and laboratory aspects of 228 cases in Colorado in 1973–1974. Ann Intern Med. 1978;88:303-310.

70 Ho M. Acute viral encephalitis. Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. vol 34. New York: North-Holland; 1978:63-81.

71 McJunkin JE, Khan R, de los Reyes EC, et al. Treatment of severe La Crosse encephalitis with intravenous ribavirin following diagnosis by brain biopsy. Pediatrics. 1997;99:261-267.

72 Burke DS, Nisalak A, Ussery MA, et al. Kinetics of IgM and IgG responses to Japanese encephalitis virus in human serum and cerebrospinal fluid. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:1093-1099.

73 Petersen LR, Roehrig JT, Hughes JM. West Nile virus encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1225-1226.

74 Solomon T, Whitley RJ. Arthropod-borne viral encephalitides. In: Scheld WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, editors. Infections of the Central Nervous System. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004:205-230.

75 Tomazic J, Poljak M, Popovic P, et al. Tickborne encephalitis: possibly a fatal disease in its acute stage. PCR amplification of TBE RNA from postmortem brain tissue. Infection. 1997;25:41-43.

76 Chandler LJ, Borucki MK, Dobie DK, et al. Characterization of La Crosse virus RNA in autopsied central nervous system tissues. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:3332-3336.

77 Lanciotti RS, Kerst AJ, Nasci RS, et al. Rapid detection of West Nile virus from human clinical specimens, field-collected mosquitoes, and avian samples by a TaqMan reverse transcriptase–PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4066-4071.

78 Goh KJ, Tan CT, Chew NK, et al. Clinical features of Nipah virus encephalitis among pig farmers in Malaysia. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1229-1235.

79 Lim CC, Lee KE, Lee WL, et al. Nipah virus encephalitis: serial MR study of an emerging disease. Radiology. 2002;222:219-226.

80 Chua KB, Goh KJ, Wong KT, et al. Fatal encephalitis due to Nipah virus among pig-farmers in Malaysia. Lancet. 1999;354:1257-1259.

81 Wong KT, Shieh WJ, Kumar S, et al. Nipah virus infection: pathology and pathogenesis of an emerging paramyxoviral zoonosis. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:2153-2167.

82 Jackson AC. Human disease. In: Jackson AC, Wunner WH, editors. Rabies. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002:219-244.

83 Warrell DA. The clinical picture of rabies in man. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1976;70:188-195.

84 Sing TM, Soo MY. Imaging findings in rabies. Australas Radiol. 1996;40:338-341.

85 Pleasure SJ, Fischbein NJ. Correlation of clinical and neuroimaging findings in a case of rabies encephalitis. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:1765-1769.

86 Anderson LJ, Nicholson KG, Tauxe RV, et al. Human rabies in the United States, 1960 to 1979: epidemiology, diagnosis, and prevention. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:728-735.

87 Hattwick MAW. Human rabies. Public Health Rev. 1974;3:229-274.

88 Warrell MJ, Looareesuwan S, Manatsathit S, et al. Rapid diagnosis of rabies and post-vaccinal encephalitides. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988;71:229-234.

89 Noah DL, Drenzek CL, Smith JS, et al. Epidemiology of human rabies in the United States, 1980 to 1996. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128:922-930.

90 Trimarchi CV, Smith JS. Diagnostic evaluation. In: Jackson AC, Wunner WH, editors. Rabies. San Diego: Academic Press; 2002:307-349.

91 Johnson RT, Griffin DE, Gendelman HE. Postinfectious encephalomyelitis. Semin Neurol. 1985;5:180-190.

92 Ploubidou A, Way M. Viral transport and the cytoskeleton. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:97-105.

93 Von Bartheld CS. Axonal transport and neuronal transcytosis of trophic factors, tracers, and pathogens. J Neurobiol. 2004;58:295-314.

94 Johnson RT, Mims CA. Pathogenesis of viral infections of the nervous system. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:23-30.

95 Davis LE, Johnson RT. An explanation for the localization of herpes simplex encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 1979;5:2-5.

96 Winkler WG, Fashinell TR, Leffingwell L, et al. Airborne rabies transmission in a laboratory worker. JAMA. 1973;226:1219-1221.

97 Tillotson JR, Axelrod D, Lyman DO. Rabies in a laboratory worker—New York. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 1977;26:183-184.

98 Constantine DG. Rabies transmission by nonbite route. Public Health Rep. 1962;77:287-289.

99 Abzug MJ, Cloud G, Bradley J, et al. Double blind placebocontrolled trial of pleconaril in infants with enterovirus meningitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:335-341.

100 Shafran SD, Halota W, Gilbert D, et al: Pleconaril is effective for enteroviral meningitis in adolescents and adults: a randomized placebocontrolled multicenter trial [Abstract]. Presented at the 39th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC), San Francisco, September 28, 1999.

101 Whitley RJ, Soong SJ, Dolin R, et al. Adenine arabinoside therapy of biopsy-proved herpes simplex encephalitis: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Collaborative Antiviral Study. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:289-294.

102 Whitley RJ, Alford CA, Hirsch MS, et al. Vidarabine versus acyclovir therapy in herpes simplex encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:144-149.

103 Griffiths P. Cytomegalovirus infection of the central nervous system. Herpes. 2004;11(Suppl 2):95A-104A.

104 Whitley RJ, Jacobson MA, Friedberg DN, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of cytomegalovirus diseases in patients with AIDS in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy: recommendations of an international panel. International AIDS Society–USA. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:957-969.

105 Jackson AC. Therapy of West Nile virus infection [Editorial]. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004;31:131-134.

106 Solomon T, Dung NM, Wills B, et al. Interferon alfa-2a in Japanese encephalitis: a randomised double-blind placebocontrolled trial. Lancet. 2003;361:821-826.

107 Boe J, Solberg CO, Saeter T. Corticosteroid treatment for acute meningoencephalitis: a retrospective study of 346 cases. BMJ. 1965;1:1094-1095.

108 Keegan M, Pineda AA, McClelland RL, et al. Plasma exchange for severe attacks of CNS demyelination: predictors of response. Neurology. 2002;58:143-146.

109 Kanter DS, Horensky D, Sperling RA, et al. Plasmapheresis in fulminant acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurology. 1995;45:824-827.