Viral Illnesses

Classification

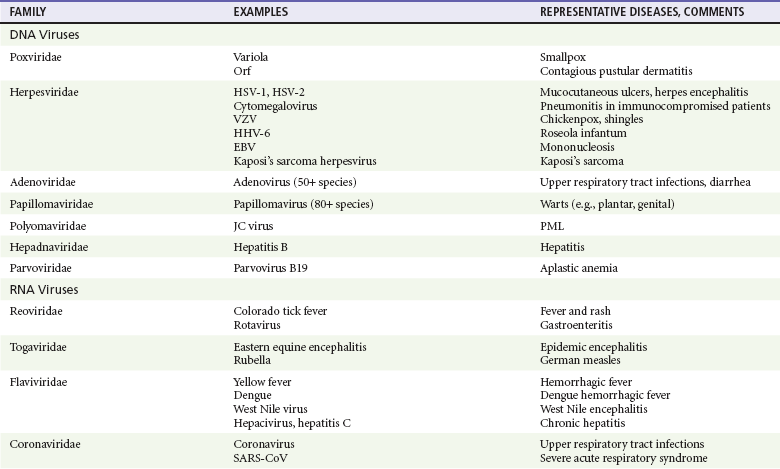

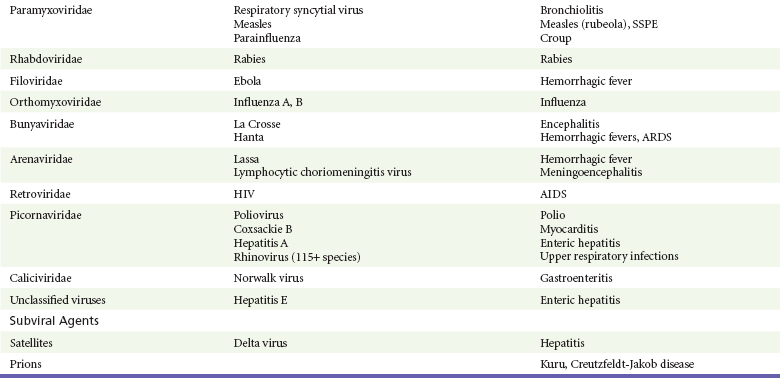

Viruses were first distinguished from other microorganisms by their ability to pass through filters of small pore size. Initial classifications of viruses were based on their pathologic properties (e.g., enteroviruses) or epidemiologic features (e.g., arthropod borne). More recently, classification has been based on the genetic relationships of the viruses. The components of the current classification are the type and structure of the viral nucleic acid, the type of symmetry of the virus capsid, and the presence or absence of an envelope (Table 130-1).

Table 130-1

Viral Immunizations

Whereas treatment strategies against most bacterial diseases have focused on eradication of bacteria from the host after disease has developed, the most successful strategies against viral diseases have concentrated on immunization, with the goal of preventing infection or illness. The history of immunization against viral diseases began in 1796, when Jenner injected pustular material from the lesions of cowpox into a child to prevent smallpox.1 The word vaccination is derived from vaccinia, referring to the skin reaction at the site of injection of such material for smallpox immunization, and originally meant “inoculation to render a person immune to smallpox.” Currently, the terms vaccination and immunization are used interchangeably to mean the administration of any vaccine. Immunization is a broader term that includes administration of immunobiologics such as immune globulins.

The modern era of immunization began in 1885, when Louis Pasteur and colleagues injected the first of 14 daily doses of rabbit spinal cord suspensions containing progressively inactivated rabies virus into 9-year-old Joseph Meister, who had been bitten by a rabid dog 2 days earlier.2 The introduction of the inactivated poliomyelitis vaccine (IPV) in 1955 and the attenuated live oral polio vaccine (OPV) in 1962 has virtually eliminated the threat of paralytic poliomyelitis in the United States and other developed countries.2,3 Currently, a massive World Health Organization (WHO) campaign to eradicate polio worldwide is under way. As of 2007, in four countries (Pakistan, India, Afghanistan, and Nigeria), polio transmission has never been interrupted, and in several more countries in Asia and Africa, polio has reemerged.4 Vaccines against measles, mumps, rubella, influenza, and hepatitis B have greatly reduced morbidity and mortality associated with these diseases. The worldwide eradication of smallpox in 1977 is a testament to the advances made against viral diseases.

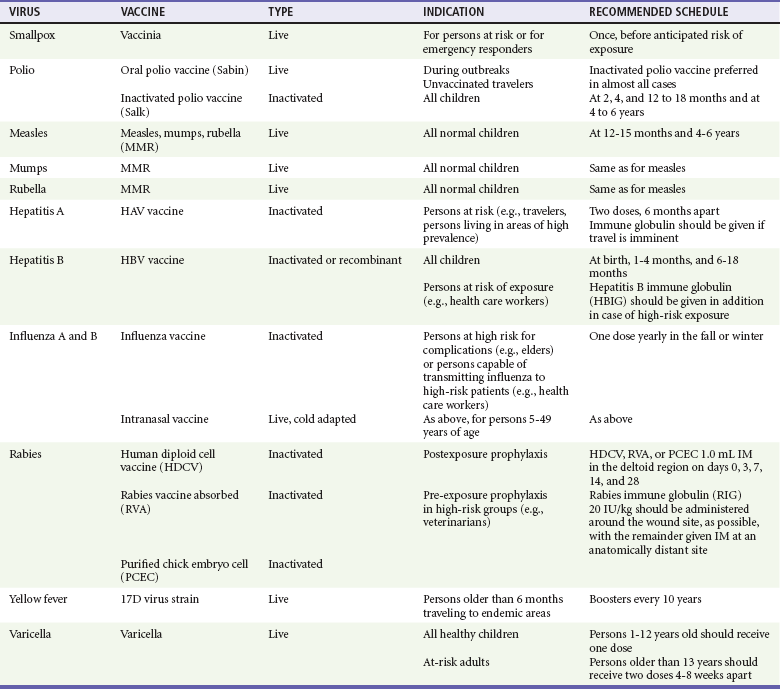

Administration of an immunobiologic agent does not automatically confer adequate immunity. Some preparations require more than one dose to produce an adequate antibody response, or periodic boosters may be needed to maintain protection. The simultaneous administration of immune globulin with a live virus vaccine may result in diminished antibody response to the vaccine. Deviation from the recommended volume or number of doses of any vaccine is strongly discouraged. Significant problems also remain in developing countries that cannot afford vaccines or have problems delivering vaccines to their at-risk populations. Table 130-2 summarizes currently available viral vaccines, their indications, and recommended uses.5–8 During the past several years, new vaccines have been developed against rotavirus,8 a major cause of diarrheal disease in young children worldwide; human papillomaviruses,9 which are associated with urogenital cancers; and herpes zoster (shingles),10 which is a major cause of morbidity in mostly elderly patients.

Antiviral Chemotherapy

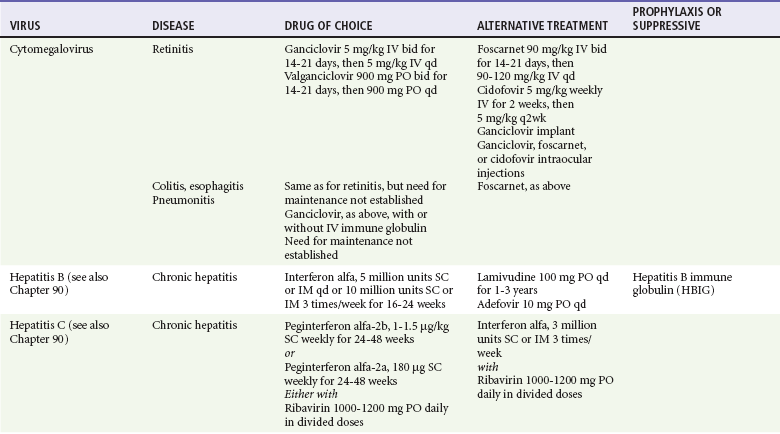

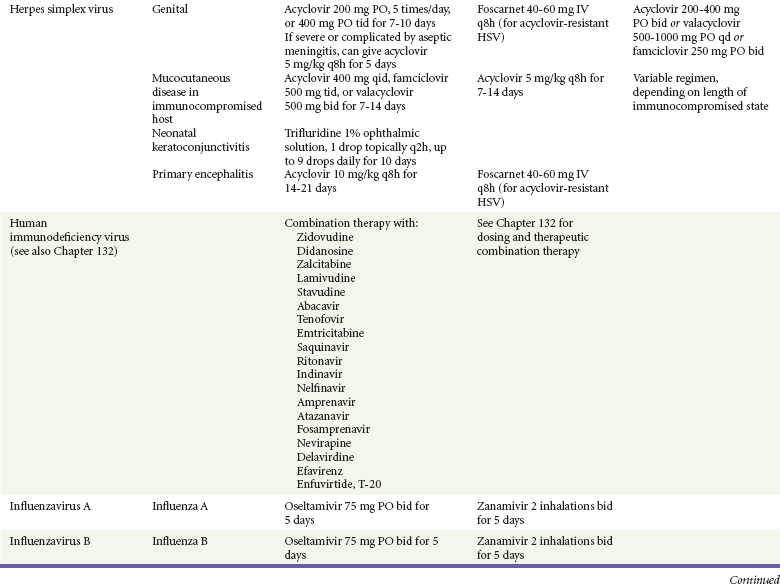

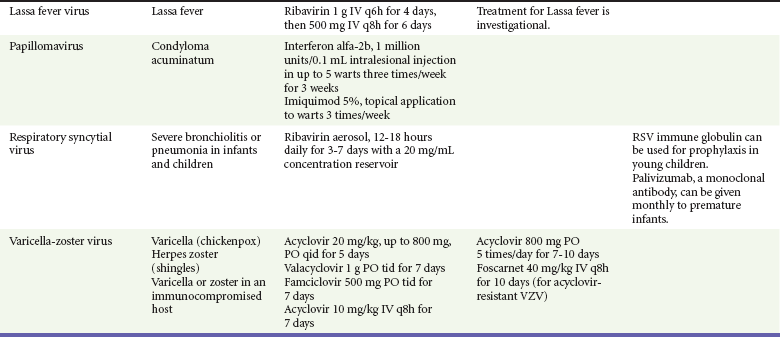

Because most viral illnesses are self-limited, treatment generally is targeted at amelioration of symptoms. The revolution in molecular biology has unlocked pathophysiologic mechanisms of viral diseases and opened up the field of viral chemotherapy. The initial therapeutic armamentarium for viral diseases has been aimed at illnesses associated with significant mortality (e.g., ribavirin for Lassa fever, acyclovir for HSV encephalitis) or those associated with significant end-organ damage (e.g., ganciclovir for cytomegalovirus [CMV] retinitis, acyclovir for ophthalmic zoster) (Table 130-3).

Amantadine and Rimantadine

Amantadine (Symmetrel) and rimantadine (Flumadine) are effective in the prevention and treatment of influenza A but have no activity against influenza B. They prevent or greatly reduce the uncoating of the viral RNA of influenza A after attachment and endocytosis by host cells. When it is initiated before exposure to influenza A, amantadine, 200 mg/day orally, is effective in preventing illness in 50 to 90% of subjects. When it is begun within 2 days after the onset of symptoms of influenza A, amantadine has reduced the duration of fever and systemic symptoms by 1 to 2 days. The drug generally is well tolerated; the most common therapy-limiting toxicities are central nervous system (CNS) effects, such as nervousness, lightheadedness, difficulty in concentrating, insomnia, and decreased psychomotor performance. These reactions occur particularly in elders who have impaired renal function; they should receive no more than 100 mg of amantadine daily. Rimantadine is mostly metabolized before renal excretion, and a lower incidence of CNS toxicity is associated with rimantadine than with amantadine. Other side effects include nausea and loss of appetite. Overdose is associated with an anticholinergic syndrome.11

During the 2005-2006 influenza season, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that amantadine and rimantadine no longer be used for treatment or prophylaxis of influenza A because of high levels of resistance among H3N2 viruses during that season.12 In 2008 the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices updated their recommendations that these antivirals not be used for the treatment or chemoprophylaxis of influenza A in the United States until evidence of their effectiveness had been reestablished among circulating influenza A viruses.13 It seems unlikely they will come back into use, given persistent findings of adamantane resistance among influenza A viruses, including pandemic H1N1.14

Zanamivir and Oseltamivir

Zanamivir (Relenza) and oseltamivir (Flumadine) were approved in 1999 for the treatment of influenza A and B. Both medications act by inhibiting the activity of neuraminidase, an enzyme involved in the release of viral progeny from infected cells. They have been shown to decrease the duration of moderate or severe symptoms of influenza by approximately 1 day. Either medication should be started within 2 days of onset of symptoms if efficacy is to be expected. Zanamivir is administered by inhalation through a novel device (Diskhaler) and is approved for use in patients older than 12 years. The dose is two inhalations twice a day for 5 days. Most of the inhaled dose is deposited in the respiratory tract and cleared unchanged in the urine or stool. The most common side effect is bronchospasm in predisposed patients. Such patients should be given a fast-acting inhaled bronchodilator before receiving zanamivir.12,15

Olestamivir is an oral medication approved for patients older than 2 weeks. The dose is 75 mg twice daily for 5 days for adults and children weighing more than 40 kg. For children younger than 1 year, the dose is 3 mg/kg twice daily. For children 1 year or older, the dose varies by weight: 30 mg twice daily for those weighing less than 15 kg, 45 mg twice daily for those weighing 15 to 23 kg, and 60 mg twice daily for those weighing 23 to 40 kg. Initial reports of influenza virus resistance to oseltamivir were followed by a rapid rise in such resistance in H1N1 strains in the United States during the 2008-2009 influenza season.16 This resistance was not seen in the H3N2 strain that was also circulating during the same season. This resulted in the CDC’s issuing interim treatment recommendations in December 2008. If treatment was based on the identification of the infecting virus, zanamivir was recommended as first-line treatment for H1N1 and oseltamivir for H3N2. If such data were not available to the treating physician, the CDC recommended that clinicians review local disease surveillance data to determine which subtype was more likely to be the offending agent and choose treatment accordingly.13 With the onset of pandemic H1N1, there were initial concerns about the need for treatment and prophylaxis of patients at risk for complications from influenza, which prompted the CDC to create interim guidelines recommending that all hospitalized persons confirmed or thought to be infected with novel H1N1 and all patients at risk for complications be treated with antiviral agents.16,17 Because of concerns about the development of resistance to oseltamivir and zanamivir in influenza A viruses, recommendations for their use were limited to the population at risk for complications. To date, 0.5% of novel H1N1 viruses submitted to a United States influenza surveillance system were found to be resistant to olsetamivir.18

Acyclovir

Acyclovir (Zovirax) is one of the drugs of choice for serious infections caused by HSV or varicella-zoster virus (VZV). Only 15 to 30% of the oral formulation is absorbed, so the intravenous form is required to treat HSV encephalitis, disseminated or ophthalmic zoster, or extensive HSV or VZV infection in the immunocompromised patient. Oral acyclovir has some use in treatment of primary HSV infections and in suppression of frequent recurrences of these infections. In general, the more immunocompromised the patient, the greater the likelihood that he or she will require intravenous acyclovir therapy. Acyclovir rarely is associated with gastrointestinal upset, reversible renal dysfunction, or encephalopathy.19

Famciclovir and Valacyclovir

Famciclovir (Famvir) and valacyclovir (Valtrex) are analogues of acyclovir that inhibit herpesvirus DNA synthesis.20,21 They are much more bioavailable than acyclovir and can be given less frequently. Both are available only as oral formulations and are effective in prevention of recurrent HSV infection.22,23

Ganciclovir

Ganciclovir (Cytovene) is used to treat life- or sight-threatening CMV infections in immunocompromised patients. Patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and CMV colitis or esophagitis may also improve with ganciclovir. Some CMV isolates in immunocompromised patients have been found to be or may become resistant to ganciclovir.24 Ganciclovir also is effective against HSV, but isolates resistant to acyclovir also are resistant to ganciclovir. The most common therapy-limiting toxic effects of ganciclovir are granulocytopenia and thrombocytopenia, which usually are reversible when therapy ceases.

Foscarnet

Foscarnet (Foscavir, trisodium phosphonoformate hexahydrate, phosphonoformic acid) is an antiviral agent with activity against the human herpesviruses and HIV-1. It has been shown to be effective against CMV retinitis in AIDS patients and in acyclovir-resistant HSV and VZV infections.25 The main limiting form of toxicity with foscarnet is renal insufficiency, which usually is reversible after the drug is discontinued. Other side effects include malaise, headache, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, anemia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia.

Interferon Alfa, Recombinant

Interferons are naturally occurring proteins with both antiviral and immunomodulating properties that are produced by host cells in response to an inducer. Injected intralesionally, recombinant preparations of interferon-alpha (interferon alfa-2a [Roferon-A], interferon alfa-2b [Intron A], peginterferon alfa-2b [PegIntron]) are effective in treatment of refractory condyloma acuminatum.26 Patients with chronic hepatitis B who have lost hepatitis B e antigen with interferon therapy have better long-term outcome with lower rates of end-stage liver disease and its complications.27 Newer agents for treatment of hepatitis B infection include lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, and telbivudine. Interferon alfa-2b combined with ribavirin has been shown to induce virologic and histologic response in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection. Therapy is discontinued because of side effects in approximately 20% of patients. The side effects of interferon therapy include fever, malaise, headache, fatigue, alopecia, and bone marrow suppression. Use of newer pegylated interferons is now standard therapy for hepatitis C.28,29

Therapy for HIV Infection

More than 30 antiretroviral drugs are currently available for the treatment of HIV infection (see Table 130-3). Treatment regimens usually include at least three of the recommended antiretroviral agents. Treatment of HIV infection is covered in Chapter 132.

Therapy for Hepatitis B Infection

At present, four antiviral agents are licensed for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B: lamivudine, adefovir, entecavir, and telbivudine. In addition, emtricitabine, tenofovir, and their combined tablet, licensed for HIV infection, are off-label options. The treatment of hepatitis B infection is highly specialized. Treatment of hepatitis B infection is covered in Chapter 90.

Vaccine-Preventable Infections of Childhood

Principles of Disease.: Mumps, or infectious parotitis, is an acute viral illness characterized by fever, swelling, and tenderness of the salivary glands, with the parotid gland most commonly involved. Mumps occurs most commonly in the winter and spring and, since the advent of widespread pediatric immunization, mostly in older children. The virus is spread by way of the respiratory tract and through direct contact with the saliva of infected people. The incubation period is 2 to 4 weeks, and the disease is communicable from 1 week before to 9 days after the onset of parotitis, with a period of maximal infectiousness approximately 2 days before the onset of illness. One third of cases are asymptomatic.

Clinical Features.: Nonsuppurative parotid swelling is the hallmark of mumps; the swelling may be unilateral. Trismus sometimes is a feature. In the first 3 days, the patient’s temperature may range between normal and 40° C. The most important but less common manifestations are epididymo-orchitis and meningitis. Orchitis occurs in 15 to 25% of postpubertal male patients and usually is unilateral. Although some degree of testicular atrophy is usual, the incidence of sterility is low, especially when the orchitis is unilateral. More than 50% of patients with mumps have a lymphocytic pleocytosis in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and hypoglycorrhachia is common; symptomatic meningitis occurs in less than 10% of cases. Encephalitis is uncommon, occurring in 1 in 6000 cases, and is the major determinant of mortality. Congenital infection is rare but may result in fetal loss if it occurs in the first trimester. Rare complications of mumps include hydrocephalus, deafness, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, pancreatitis, mastitis, oophoritis, myocarditis, and arthritis.

Differential Considerations.: In children, the diagnosis of mumps is made by a history of infectious exposure and the presence of parotid swelling and tenderness in association with constitutional symptoms. Laboratory confirmation generally is not required. Considerations in the differential diagnosis include other viral infections and other causes of parotid swelling and tenderness, such as bacterial parotitis or sarcoidosis.

A multistate outbreak of mumps was reported in the United States in 2006, with almost 6000 reported cases.30 Because the likelihood of infection was five times higher in persons who had received only one dose of mumps vaccine as opposed to those who had received two doses of the vaccine, updated recommendations that all persons receive two doses of mumps vaccine were introduced by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices.31

Measles Virus (Rubeola)

Principles of Disease.: Measles is a highly communicable viral illness acquired as an infection of the respiratory tract. In general, all susceptible people exposed to an active case will acquire infection. After multiplication in the respiratory mucosa, the virus spreads to regional lymphoid cells and then travels in the bloodstream to leukocytes in the reticuloendothelial system. The clinical manifestations appear after a second viremic phase.

Before the availability of an effective vaccine in 1963, measles was a ubiquitous disease. In 2006, measles accounted for approximately 240,000 deaths globally; in view of higher death rates in previous years, it is clear that great strides have been made to decrease measles deaths in many areas of the world. Measles continues to be a leading cause of death in young children, especially those living in developing countries.32 Endemic measles in the United States has been eradicated, although the disease continues to occur among inadequately vaccinated persons who, in most instances, have been exposed to the disease by someone who has been infected abroad. A recent increase in the number of reported measles cases has been linked to travel abroad and unvaccinated status.33,34 Measles is a reportable disease, and the local health authority should be contacted. Children should be kept out of school for at least 4 days after the appearance of the rash.

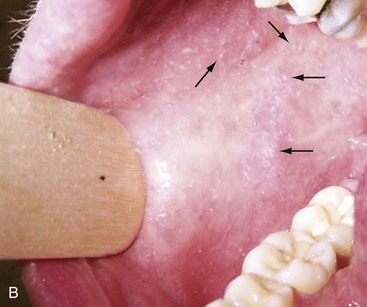

Clinical Features.: The incubation period of measles is 10 to 14 days. Cough, coryza, conjunctivitis, and fever precede development of the characteristic rash by 2 to 4 days (Fig. 130-1A). Pinpoint grayish spots surrounded by bright red inflammation (Koplik’s spots) typically are found on the lateral buccal mucosa before the appearance of the rash and are considered pathognomonic for measles (Fig. 130-1B). Discrete red macular and papular lesions begin on the head and progress downward during a period of 3 days to cover the entire body. Laryngitis, tracheobronchitis, bronchiolitis, and pneumonitis may accompany the disease. Bacterial superinfections occasionally delay recovery. A rare acute encephalomyelitis, associated with a mortality rate of 25%, can complicate recovery. Unlike rubella, measles acquired during pregnancy is not teratogenic but may result in stillbirth or premature delivery.

Differential Considerations.: The diagnosis is made primarily on the basis of clinical characteristics. Other viral exanthems may at times be manifested with a similar rash.

Management.: Treatment of the primary disease is supportive. Immunocompromised children and infants younger than 1 year who are susceptible and have been exposed to measles can be given passive immunization within 6 days of exposure. Healthy infants should receive 0.25 mL/kg of immune globulin intramuscularly, and immunocompromised children should be given 0.5 mL/kg intramuscularly, up to 15 mL.

Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis

Principles of Disease.: Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) is a degenerative disease of the brain caused by measles virus or a defective variant that persists in the CNS after primary measles. SSPE has virtually disappeared in the United States since the 1970s, approximately 10 years after measles vaccination began.

Clinical Features.: SSPE is a subacute encephalitis involving both the white and the gray matter of the cerebral hemispheres and brainstem and follows 1 in 100,000 cases of measles. It generally occurs in patients with a history of an uncomplicated case of primary measles that occurred at a younger than average age. Five to 10 years later, SSPE is manifested with myoclonus and variable focal neurologic deficits. Progressive neurologic degeneration ensues, and death usually occurs within months to years of diagnosis.

Rubella Virus (German Measles)

Clinical Features.: Rubella is a mild febrile illness associated with a diffuse maculopapular rash, fever, malaise, headache, and postauricular, occipital, and posterior cervical lymphadenopathy (Fig. 130-2).

Figure 130-2 Rubella.

Differential Considerations.: The rash associated with rubella (third disease) is one of the classic common exanthems of childhood. It may be similar to the rash of measles (rubeola, or first disease), scarlet fever (second disease), a variant of scarlet fever or toxin-producing staphylococcal disease (fourth disease), erythema infectiosum (fifth disease), and roseola (exanthema subitum, or sixth disease).

Management.: Rubella control is required to prevent birth defects in the offspring of women who have the disease during pregnancy. In the United States, vaccination to prevent rubella is recommended for all children at the age of 15 months. Vaccination results in a greater than 95% seroconversion rate. Because of the production of a transient viremia, pregnancy should be delayed for 3 months after a susceptible woman has been vaccinated. No cases of the congenital rubella syndrome attributable to rubella vaccine occurred in more than 300 women inadvertently vaccinated during pregnancy who carried their infants to term.35 There is no evidence of decreasing immunity with age. Persons with rubella should be cautioned to avoid contact with susceptible women. Because of an increasing failure to vaccinate susceptible persons, a moderate resurgence of rubella and a major increase in the congenital rubella syndrome in the United States occurred in 1990. Since then, a general decline in rubella incidence has been observed, but outbreaks continue to occur, especially among foreign-born adults.

Specific Viral Diseases by Presenting Clinical Syndrome

Viral Diseases with Significant Dermatologic Manifestations

Poxviridae

Perspective.: The elimination from the natural environment of variola virus, the virus that causes smallpox, at one time the most devastating worldwide pestilence, is one of the great medical and public health accomplishments of the past century.5 The elimination of smallpox from the natural environment was possible because of the lack of nonhuman reservoirs or human carriers of variola and the availability of rapid diagnostic techniques and an effective vaccine. Global eradication was certified by the WHO in 1980. Other human poxvirus diseases include monkeypox, vaccinia virus infection, molluscum contagiosum, orf, and paravaccinia virus infection. The poxviruses are the largest pathogenic viruses, consisting of complex, brick-shaped capsids and double-stranded DNA.

Variola (Smallpox), Monkeypox, Vaccinia, and Cowpox Viruses.: Within the Poxviridae family, the Orthopoxvirus genus contains at least nine homogeneous viruses, including variola, vaccinia, cowpox, and monkeypox viruses. The last naturally acquired case of smallpox occurred in Somalia in October 1977. Two cases occurred in 1978 in Birmingham, England, related to a research laboratory accident.

Principles of Disease.: Recently, the possibility that military and research stores of virus could become weaponized and used as tools of terrorism or war has mandated that health care professionals familiarize themselves with the manifestations of smallpox, the clinical manifestations of vaccine-related illness, and the risks and benefits of the vaccine. The CDC has established extensive web-based information and training materials in preparation for the possibility of an outbreak.

Clinical Features.: Smallpox is transmitted by infected droplets or close contact with a patient in any stage of illness. The most common manifestation in the unvaccinated host is variola major, which has a fatality rate of approximately 30%. The illness is characterized by a short prodrome of headache, backache, and fever. An ensuing enanthem progresses from small macules to papules and then vesicles during a few days. Lesions begin on the face and limbs and spread in a centrifugal pattern. These develop into 4- to 6-mm firm, deep-seated vesicles or pustules that umbilicate, crust, and then desquamate in the next several weeks (Fig. 130-3). All lesions are at the same stage of development. Modified, milder forms of smallpox can appear in previously vaccinated patients and, more rarely, in nonimmune hosts. There are also two more rare but almost uniformly fatal forms of smallpox: a fulminant, “hemorrhagic” form and “flat type” smallpox, characterized by plaquelike lesions.36

Figure 130-3 Smallpox.

Diagnostic Strategies.: Major criteria for diagnosis include a prodrome of 1 to 4 days with fever (temperature higher than 38.3° C) and symptoms and signs such as headache and vomiting. Minor criteria include a centrifugal distribution of the rash, lesions on the palms and soles, a toxic appearance, and a rash that develops during several days. Routine laboratory tests are not helpful in the diagnosis. In the prodromal phase, there may be a relative granulocytopenia, but the white blood cell count usually is elevated in the eruptive phase. Laboratory diagnosis can be established by antibody testing, cell culture, or electron microscopy.

Differential Considerations.: Smallpox has been confused with other papulovesicular eruptions, including varicella (chickenpox), measles, erythema multiforme, molluscum contagiosum, generalized vaccinia virus infection, and monkeypox. The lesions of chickenpox generally are at different stages of development and healing and often spare the palms and soles.

Management.: The CDC guidelines classify suspected cases of smallpox into categories of high, moderate, and low risk. Cases with high or moderate risk should prompt appropriate isolation and consultation with an infectious disease specialist or local health care authority. Quarantine, contact tracing, and immunization efforts are a priority for public health officials, and prompt involvement of the appropriate agencies will be crucial to containment efforts in the event of an outbreak.

Perspective.: The origin of the vaccinia virus is not well established, but it is the poxvirus that is used to produce the smallpox vaccine. Although primary infection (through live virus vaccination) or secondary infection (from virus shed from an immunized patient) with vaccinia virus is usually well tolerated, severe local reactions from immunization as well as disseminated severe manifestations of primary or secondary infection have been well described. The normal reaction to vaccinia vaccine is a localized inflammatory reaction with scar formation. Viremia is possible, but manifestations are of a mild viral illness. In immunocompromised hosts, such as some young infants or persons with aberrant cell-mediated immunity, a syndrome of multiplying and aggressive necrotic skin lesions called progressive vaccinia can lead to death.

Perspective.: Edward Jenner, in his An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae in 1798, observed that on inoculation into humans, the pustular material from the lesions of cowpox protected them from infection with smallpox.1 Cowpox virus is similar to vaccinia virus and is found mostly in Europe, countries of the former Soviet Union, and Central Asia. It has natural reservoirs in wild animals but can also cause infection in domesticated animals, including cattle and cats.

Clinical Features.: In the immunocompetent human host, the disease is limited to a vesiculopustular, scabbing eruption that is often localized and can be accompanied by an influenza-like syndrome. In immunocompromised hosts and person with eczematous eruptions, the disease is more aggressive and sometimes fatal. There appears to be an increase of cowpox cases in Europe that is thought to be due to waning smallpox immunity and increased exposure to the disease from wild animal reservoirs.38

Clinical Features.: The disease of monkeypox is clinically similar to that of smallpox. Most cases have occurred in west and central Africa, with a case fatality rate of 1 to 10% and higher death rates among children. An outbreak of 72 cases in the Midwest United States in spring 2003 was traced to contact with prairie dogs housed with Gambian giant rats that were imported from Ghana.39 No deaths were associated with this outbreak. There seems to be an increase in monkeypox cases that could be attributable to decreased cross-immunity from the cessation of smallpox vaccination as well as to increased human exposure to rainforest wildlife from hunting “bush meat.” Monkeypox has also been seen as a potential biowarfare agent, but the greater threat for global spread of the disease comes from the illegal international trade of exotic animals.40

Parapoxviruses, Molluscum Contagiosum, and Tanapox Viruses:

Perspective.: Other viruses within the Poxviridae family that cause disease in humans include the parapoxviruses (paravaccinia virus and bovine pustular stomatitis virus) and the molluscum contagiosum and tanapox viruses.

Clinical Features.: The milker’s node virus, or paravaccinia virus, produces vesicular lesions on the udders or teats in cattle and is transmitted to humans by direct contact. Milker’s nodules, which develop on the fingers or hands, are small, watery, painless nodules occasionally associated with lymphadenopathy. The lesions generally resolve completely within 3 to 8 weeks.

Molluscum contagiosum is a generally benign human disease characterized by multiple small, painless, pearly, umbilicated nodules. They appear on epithelial surfaces, commonly in anogenital regions, and may be spread through close contact or autoinoculation. In immunocompetent persons, the lesions may clear rapidly or persist for up to 18 months. The infection often is seen in patients with HIV infection, in whom the lesions often are not restricted to the genital area and may increase in size and number.41 Curettage or other forms of local ablation may be helpful in such recalcitrant cases.

Herpesviridae

Principles of Disease.: At least eight human herpesviruses are known. Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2) are the agents of herpes genitalis, labialis, and encephalitis. Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is the etiologic agent of chickenpox and herpes zoster. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is the agent of infectious mononucleosis and also is associated with nasopharyngeal carcinoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma, and other lymphoproliferative syndromes. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is associated with heterophil-negative infectious mononucleosis and invasive disease in immunocompromised patients. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is associated with roseola infantum.42 The role of human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7) has not been completely elucidated. Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) is associated with Kaposi’s sarcoma,43 body cavity–based lymphomas, and multicentric Castleman’s disease. In addition, a closely related monkey virus, herpesvirus simiae or herpes B virus, has been shown to cause fatal encephalitis in humans.

Principles of Disease.: A localized primary lesion, latency, and a tendency for local recurrence characterize infections with HSV-1 and HSV-2 (herpesvirus hominis). The primary lesion with HSV-1 may be mild and inapparent; the first outbreak may occur during childhood. Reactivation of latent HSV-1 infection usually results in herpes labialis (cold sores, fever blisters). Neurologic involvement is not uncommon with HSV-1. Although such involvement usually occurs in association with a primary infection, neurologic signs may appear after a recrudescence and may be manifested as encephalitis. Although it is uncommon, HSV-1 encephalitis is one of the most common causes of encephalitis in the United States, with estimates of several hundred to several thousand cases occurring yearly. HSV-2 most commonly is associated with genital herpes, although either HSV-1 or HSV-2 may infect any mucous membrane, depending on the route of inoculation. HSV-2 is commonly associated with aseptic meningitis rather than with meningoencephalitis. The incubation period for primary herpes infection is 2 to 12 days.44

Clinical Features.: Primary HSV-1 often is asymptomatic but may appear as pharyngitis and gingivostomatitis in children younger than 5 years. Associated with fever, pharyngeal edema, erythema, cervical adenopathy, and multiple small vesicles that ulcerate and multiply, the disease generally lasts 10 to 14 days. Recurrences develop in 60 to 90% of people after primary infection but generally are milder than the primary infection. Vesicles generally recur on the vermilion border, usually are small, and crust within 48 hours.

Neonatal herpes infection occurs in 8 to 60 in 100,000 births, depending on the population of patients studied, and is caused by the transmission of the virus at the time of delivery. Most babies with neonatal herpes infection are born to asymptomatic mothers, but there appears to be a much higher risk of transmission by a mother who experiences the first genital herpes infection during pregnancy. It is estimated that 50 to 80% of infants with neonatal herpes are born to mothers who acquire genital herpes infection near term. This might indicate that women with long-standing infection transmit antibody to the fetus that decreases disease manifestation after exposure to virus during birth.45 The use of invasive monitoring and premature delivery also are associated with an increased risk of infection.46 Infection may be manifested after several days to weeks with vesicles or conjunctivitis; neurologic involvement, with seizures, cranial nerve palsies, lethargy, and coma, is common. Untreated disseminated or CNS disease is fatal in more than 70% of patients.

Diagnostic Strategies.: CSF findings are nonspecific, with a moderate mononuclear pleocytosis. Results of culture of the CSF generally are negative for HSV. Localization of the encephalitis within the temporal lobes by electroencephalography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computed tomography (CT) scan increases the likelihood of a diagnosis of HSV encephalitis. The diagnosis of HSV encephalitis can be made reliably only with a biopsy of the lesion and subsequent isolation or detection of the virus by culture, direct fluorescent antibody tests, or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay.

Differential Considerations.: The superficial lesions of HSV infection are indistinguishable from those of VZV infection. Pharyngitis and gingivostomatitis in children can mimic streptococcal or diphtheritic pharyngitis, herpangina, aphthous stomatitis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, Vincent’s angina, or infectious mononucleosis. Primary genital herpes can mimic the appearance of chancroid, syphilis, candidiasis, or Behçet’s syndrome. In the neonate, in the absence of vesicles, congenital HSV infection can mimic disease caused by rubella, CMV, or Toxoplasma organisms. Encephalitis caused by HSV may be clinically indistinguishable from other viral encephalitides, tuberculous and fungal meningitis, brain abscesses, brain tumors, and cerebrovascular accidents.

Management.: Oral acyclovir (400 mg three times daily), oral valacyclovir (1 g twice daily), or intravenous acyclovir (5 mg/kg three times daily) is recommended for treatment of primary genital herpes or mucocutaneous herpes in the immunocompromised host, although some authorities use higher dosages in these patients despite no clear evidence.47 Because of the safety and efficacy of oral acyclovir, there is little indication for use of acyclovir ointment. In people with severe or frequent recurrences, acyclovir, ranging in doses from 200 mg five times daily to 800 mg once daily, can be used as an effective suppressive regimen. Both famciclovir and valacyclovir also are approved for suppressive therapy and daily dosing of the affected partner in an HSV-discordant couple; a 500-mg dose of valacyclovir yielded about a 50% reduction in transmission to the unaffected partner in a recent study.45

Several vaccines against HSV have reached differing phases of development and testing, but none has shown enough promise to become clinically available.48 Research in this area is ongoing.

Disposition.: Patients with cutaneous HSV infections generally can be managed easily. The diagnosis often carries with it a great deal of stigma that should be addressed. Assurance of the generally benign nature of the infection is helpful. Counseling should include cautions about the transmissibility of the virus, even during asymptomatic periods. Women of childbearing age should discuss management of HSV infection during pregnancy and delivery with their obstetricians. It is clear that shedding of HSV occurs when there is no clinical outbreak in persons with a history of recurrent lesions and that persons who have never had recognizable lesions but who have antibody to HSV can also shed virus. With the advent of dependable commercialized serologic tests for HSV-1 and HSV-2, it is hoped that clinicians will be better able to identify persons with asymptomatic infection and to provide counseling on ways to decrease transmission. There are no clear current guidelines for how to decrease such transmission, but the routine use of condoms and suppressive therapy with antiviral medications are reasonable until more research in the field is conducted.

Principles of Disease.: VZV, or human (alpha) herpesvirus 3, is the agent of both chickenpox and herpes zoster, or shingles.

Clinical Features.: Chickenpox is an acute, generalized viral disease characterized by sudden onset of fever, malaise, and a skin eruption that initially is maculopapular and then becomes vesiculated for several days before a granular scab is left (Fig. 130-4). Lesions occur in crops, with several stages present at the same time. Lesions can appear anywhere on the skin and mucous membranes. There may be few lesions and mild, inapparent infections. Most cases occur in children younger than 9 years; adults with the disease may have high fevers and severe constitutional symptoms. Children with acute leukemia are at increased risk for disseminated disease, which carries a case fatality rate of greater than 5%. Neonates in whom varicella develops before 10 days of age and mothers who contract the disease in the perinatal period are at increased risk for generalized infection. Fatal disease in adults, although uncommon, usually is associated with pneumonic involvement. In children, fatal disease usually is associated with septic complications and encephalitis.

Figure 130-4 Chickenpox.

Herpes zoster is due to reactivation of VZV that has been latent in a dorsal root ganglion after an episode of chickenpox; it occurs predominantly in older adults and those with an immunocompromised state, such as HIV infection.49 There are about 1 million cases in the United States annually.50 The rash is often preceded by tingling or hypesthesia; multiple vesicles on an erythematous base appear in crops along nerve pathways supplied by sensory nerves of a single dorsal root ganglion or an associated group of dorsal root ganglia. The distribution usually is unilateral and dermatomal (Fig. 130-5). The lesions often are extremely painful. Postherpetic neuralgia, which is defined as continued pain for 6 months after lesions have healed, is more likely to occur in elders with larger and more painful rashes. It can last for months or years and is refractory to treatment. Ophthalmic infection, which can occur without other cutaneous lesions, can lead to corneal ulceration. Two relatively rare but often cited facial zoster infections are Hutchinson’s sign, which is the appearance of a blister on the tip of the nose with herpes ophthalmicus, and Ramsey Hunt syndrome, which is characterized by localized pain, facial weakness, and a rash of the face or ear canal that can be subtle.51

Figure 130-5 Herpes zoster.

Diagnostic Strategies.: Both chickenpox and herpes zoster are often easily diagnosed on physical examination, and laboratory tests generally are not required. Multinucleated giant cells may be seen on Tzanck preparations of material from the base of a lesion but will not allow differentiation of HSV from VZV lesions. Submission of scrapings for a direct fluorescent antigen test is cost-effective and allows differentiation of VZV from HSV infection.

Management.: Use of acyclovir for uncomplicated chickenpox in children is safe but only modestly effective. Parents of children with chickenpox should be cautioned not to give their children aspirin or aspirin-containing compounds because of the strong association between this practice and the development of Reye’s syndrome.52 Acetaminophen can be used as an antipyretic. Adults experience increased morbidity and mortality from chickenpox, so treatment of otherwise healthy adults with acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir frequently is indicated. Patients with pneumonitis or other severe illness should be treated with intravenous acyclovir. In immunocompromised patients, varicella-zoster immune globulin and intravenous acyclovir have been shown to decrease morbidity.

A live, attenuated vaccine that shows a high degree of protection for both normal children and children with leukemia was licensed in the United States in 1995. It is recommended for immunocompetent people older than 12 months. In those older than 12 years, two doses of vaccine are to be administered 4 to 8 weeks apart. It also is recommended for use as postexposure prophylaxis in the nonimmune host. The vaccine is most effective in preventing or attenuating illness in these circumstances if it is administered within the first 3 to 5 days after exposure.53 The vaccine is a live attenuated virus and not recommended for use in immunocompromised patients.

Uncomplicated herpes zoster generally is treated with supportive measures, especially pain control, and antivirals (acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir). The currently recommended dosages are 800 mg five times a day for acyclovir, 500 mg three times a day for famciclovir, and 1 g three times a day for valacyclovir. Both famciclovir and valacyclovir are preferred to acyclovir because of increased compliance. In addition, there are data that valacyclovir 1.5 g twice a day yields equivalent therapeutic effect, and one might guess that compliance may be improved with dosing twice a day compared with three times a day, but this regimen is not currently approved for the treatment of herpes zoster.54 There is good evidence that treatment with antivirals reduces the incidence and severity of postherpetic neuralgia, and treatment should be considered for those most at risk for this complication, such as those with large painful rashes and those 50 years of age or older.54 Treatment with intravenous acyclovir should be considered for patients with disseminated disease and complicated zoster (involving more than one dermatome). Susceptible immunocompromised patients exposed to infected persons should receive varicella-zoster immune globulin within 72 hours to prevent or to modify clinical illness. Foscarnet is useful for treatment of infections due to acyclovir-resistant VZV in immunocompromised patients.

The use of corticosteroids to decrease the incidence of postherpetic neuralgia is controversial. A recent Cochrane review could not support the practice.55 Nevertheless, the use of corticosteroids in conjunction with antivirals in persons who are at highest risk for postherpetic neuralgia and do not have contraindications to systemic steroid therapy is condoned by reliable sources. Herpes zoster is estimated to eventually occur in approximately 30% of the population; the introduction of an effective vaccine led to the recommendation that immunocompetent persons older than 60 years be vaccinated with one dose of varicella-zoster vaccine.

Disposition.: Chickenpox and herpes zoster are highly contagious. Although these diseases generally are benign, patients should avoid situations that put them in contact with steroid-treated or immunocompromised persons. The incubation period most commonly is 13 to 17 days, and the period of communicability may range from 5 days before to 5 days after the appearance of the vesicles. Susceptible persons should be considered potentially infectious from 10 to 21 days after exposure. Susceptible health care workers should not care for people with varicella or zoster. Health care workers without a well-documented history of chickenpox or herpes zoster should have antibody levels checked before they begin their employment to determine susceptibility to VZV, and they should strongly consider vaccination if they prove to be nonimmune.

Principles of Disease.: HHV-6 has been implicated as an agent of roseola infantum (exanthema subitum).

Clinical Features.: Roseola infantum is the most common exanthem of children younger than 2 years and occurs most often at approximately 1 year of age. The illness begins abruptly with the acute onset of fever, with temperature often as high as 41° C, lasting 3 to 5 days. A fine, evanescent, rose-colored maculopapular rash appears on the trunk after lysis of the fever and lasts 1 to 2 days. The rash may spread to the face and extremities. Most cases are self-limited, and despite the fever, the child usually remains active and alert. There is conflicting evidence on the frequency of HHV-6–associated febrile seizures.56,57 Although secondary cases occur after an incubation period of approximately 10 days, most cases of roseola occur without known exposure.

Human Herpesvirus 7.: HHV-7 has been associated with a clinical presentation similar to that for HHV-6, but its role in disease has not yet been fully elucidated.58

Human Herpesvirus 8.: HHV-8 has been implicated as the cause of Kaposi’s sarcoma regardless of the HIV serostatus of the affected patient. HHV-8 is also implicated in Castleman’s disease, which is also known as angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia.59 Mechanisms of disease pathogenesis as well as epidemiology of transmission for this virus remain unclear and continue to be actively investigated.

Principles of Disease.: Herpes B virus, or herpesvirus simiae, a close relative of human HSV, is enzootic in macaques and most commonly is associated with rhesus, cynomolgus, or African green monkeys. Like human HSV, herpes B virus produces mild disease in monkeys that is characterized by intermittent reactivation and shedding, particularly during times of stress, such as during handling. Among monkey handlers and those exposed to the animals’ saliva or tissues, monkey B virus is a serious occupational hazard and is associated with a high proportion of progressive mucocutaneous disease and fatal encephalitis in infected patients.60 The first known case of fatal herpes B virus infection, from a mucosal splash exposure, occurred in 1998.

Clinical Features.: After a penetrating bite or scratch from an infected monkey, herpetiform vesicles may form at the site of the injury. Giant cells can be seen on a Tzanck preparation. An acute febrile illness with headache and lymphocytosis may follow as late as 3 weeks after the injury. An ascending myelitis ensues, leading to death from respiratory paralysis or encephalomyelitis within 3 weeks of onset of symptoms. The incidence of asymptomatic infection is unknown.

Differential Considerations.: The initial skin lesions appear similar to those of herpes simplex. In the context of any exposure to monkey tissues and the appearance of a herpetiform lesion, the diagnosis of herpes B virus infection must be considered because of its associated high mortality rate.

Management.: The most important step that can be taken to prevent B virus disease is thorough cleansing of exposed tissues. Current recommendations are that mucous membranes be flushed with sterile saline or water for 15 minutes and that areas of exposed skin be washed for 15 minutes with a detergent or a solution containing disinfectants (such as chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine). Affected tissue (except ocular or mucous membranes) can be initially washed with 0.25% hypochlorite (Dakin’s) solution before being washed with a detergent solution.

The decision to initiate postexposure prophylaxis is based on the severity of the exposure and the appropriateness of first aid measures. Postexposure prophylaxis does not need to be initiated if the exposed skin is intact or the exposure is to a nonmacque species of monkey. Valacyclovir, 1 g orally every 8 hours for 14 days, is recommended for postexposure prophylaxis.60

Papillomaviridae

Principles of Disease.: Human papillomavirus (HPV) infections are common in all human populations and are the cause of a variety of cutaneous and mucous membrane lesions, including common warts, anogenital or venereal warts (condyloma acuminatum), and respiratory or laryngeal papillomas.

More than 70 types of HPVs have been identified. Laryngeal papillomas (most commonly caused by HPV types 6 and 11) and genital warts (most commonly caused by HPV types 16 and 18) can undergo malignant transformation.61 In addition, HPV has been implicated as a causative agent for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas that have been traditionally attributed mainly to other causative agents, such as cigarettes. This observation has led to the prospect that vaccination against HPV might reverse the increasing incidence of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas attributable to HPV infection.62 The association between HIV infection and more aggressive forms of HPV infection, including a greater likelihood for malignant transformation of lesions, has been shown.63

Clinical Features.: Common warts generally are well-circumscribed, hyperkeratotic, painless papules occurring most commonly on the extremities and transmitted by close personal contact. Plantar warts, found on the soles of the feet, may be very painful. Venereal warts, found on the internal or external genitalia or perianal region, are hyperkeratotic, exophytic papules, either sessile or pedunculated, and are sexually transmitted. Laryngeal papillomas in children presumably are acquired during passage through the birth canal. Malignant transformation can occur, particularly in patients receiving radiation therapy.

Differential Considerations.: The diagnosis of warts usually is made clinically. Condyloma acuminatum must be distinguished from the condyloma latum of syphilis.

Diagnostic Strategies.: Diagnosis of cervical HPV infections can be made during colposcopy with previous application of a 3 to 5% acetic acid solution to the internal genital tract. Flat condylomata appear as shiny white patches with ill-defined borders and irregular surfaces. Acetowhitening also can reveal subclinical vulvar or penile warts.

Management.: Genital warts generally regress spontaneously within months or years, and it is unclear whether their removal decreases infectivity or decreases the chance of malignant transformation. Therapy is at the discretion of the patient and the caregiver. Patient-applied therapies use podofilox 0.5% gel or imiquimod 5% cream. Freezing with liquid nitrogen, surgical removal, and intralesional interferons also are effective for most accessible lesions. Combination therapies also can be used. Salicylic acid plasters and curettage are useful for plantar warts. Laryngeal warts require surgery or laser therapy.

Parvoviruses (Erythema Infectiosum):

Principles of Disease.: Parvovirus B19 has been implicated as the causal agent in several epidemics of erythema infectiosum or fifth disease. It also is associated with transient aplastic crisis in patients with chronic hemolytic disease, particularly those with sickle cell disease. Infections during pregnancy have been associated with hydrops fetalis and spontaneous abortion.64 Humans constitute the only reservoir for parvovirus B19. Transmission usually occurs through contact with aerosol or respiratory secretions. Transmission by contaminated blood products has been documented.

Clinical Features.: Erythema infectiosum is a mild, usually nonfebrile disease of children between 4 and 10 years of age, characterized by a striking erythema of the cheeks—a “slapped-cheek” appearance (Fig. 130-6). The rash usually appears after an incubation period of 4 to 14 days without a prodrome. One to 4 days later, an erythematous rash on the extremities may be seen spreading to the trunk in a lacelike pattern. The rash generally fades within a week but can persist for several weeks, and recrudescence can be precipitated by skin trauma or sunlight exposure. Constitutional symptoms generally are mild in children, but adults with the disease commonly have associated arthralgias and arthritis. Rare cases of encephalitis and pneumonia have been reported.

Figure 130-6 Erythema infectiosum.

Differential Considerations.: In children, erythema infectiosum resembles other viral exanthems. The slapped-cheek appearance of the rash is characteristic.

Management.: Erythema infectiosum generally is a mild disease, and no treatment is required. Patients with parvovirus B19–associated aplastic crisis may require blood transfusions. Therapy with immune globulin can lessen the need for transfusions in immunosuppressed patients with chronic anemia. Women in whom parvovirus infection develops during pregnancy should be observed closely for the development of nonimmune fetal hydrops. The role of intrauterine blood transfusions in the treatment of this disorder remains controversial.65

Mononucleosis and Viral Diseases That Present with Mononucleosis-like Syndrome

Epstein-Barr Virus (Infectious Mononucleosis):

Principles of Disease.: EBV, or human herpesvirus 4, most commonly is associated with infectious mononucleosis, an acute viral syndrome characterized by fever, exudative pharyngotonsillitis, lymphadenopathy, and peripheral lymphocytosis with atypical lymphocytes.

EBV infects and transforms B lymphocytes. Infection is common and widespread in early childhood in developing countries, where it usually is mild or asymptomatic. In developed countries, infectious mononucleosis usually is manifested in older children and young adults, commonly among high school and college students. It is transmitted by way of the oropharyngeal route, often by kissing. The incubation period may be as long as 4 to 6 weeks, and pharyngeal excretion can persist for 1 year or more. A chronic form of the disease has been suggested as the cause of chronic fatigue syndrome, but recent data do not support this association.66

EBV also has been strongly implicated in the pathogenesis of African Burkitt’s lymphoma and nasopharyngeal carcinoma. EBV is also expressed by Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells and is more frequently seen in certain groups of patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, such as children.67 Other lymphomas in immunocompromised patients, such as renal transplant recipients or persons with AIDS, also have been associated with EBV infection.

Clinical Features.: Acute mononucleosis is a mild disease in most children. Those who acquire the disease as adults tend to have more symptomatic disease classically described as a syndrome of severe exudative pharyngitis, fevers, lymphadenopathy, and fatigue. About 95% of young adults have abnormal transaminases and 4% have jaundice. Hepatosplenomegaly is common. The disease generally resolves in 1 to 3 weeks, but malaise and fatigue rarely can persist for several months. On occasion, tonsillar swelling causes respiratory compromise. Splenic rupture is rare but should be considered in patients with left upper quadrant pain and a falling hematocrit. Neurologic complications, including encephalitis, aseptic meningitis, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, optic neuritis, and peripheral neuropathies, occur in less than 1% of patients.

Diagnostic Strategies and Differential Considerations.: Laboratory diagnosis is based on the finding of lymphocytosis (more than 50% of the total white blood cell count) or an elevation in heterophil antibodies (Monospot test). Heterophil antibodies are sensitive and specific antibodies that usually appear early in the illness. Other assays for virus-specific antibodies are available but rarely are needed to diagnose mononucleosis because the patient is heterophil seropositive in 90% of cases.

Management.: Treatment is supportive only, except when rare complications of organ compromise are present. The use of corticosteroids in uncomplicated illness is controversial. These agents generally are used for impending airway obstruction, hemolytic anemia, or severe thrombocytopenia. Infection confers a high degree of resistance to reinfection. Patients should be cautioned about potential communicability to previously uninfected people.

Principles of Disease.: CMV, or human herpesvirus 5, commonly is associated with heterophil-negative infectious mononucleosis syndrome and is clinically and hematologically similar to EBV-associated mononucleosis. More severe infections with CMV occur in the perinatal period and among immunocompromised patients. Severe CMV infections also are found in transplant recipients when organs from CMV-seropositive donors are transplanted into CMV-seronegative recipients.

Clinical Features.: CMV infection in immunocompetent older children and adults generally is subclinical. It is characterized by fever, lymphadenopathy, exudative pharyngitis, and peripheral lymphocytosis, with atypical lymphocytes present on peripheral blood smears. The acute infection resolves in 2 to 4 weeks, but malaise and viral excretion can persist for months. In the perinatal period, severe, generalized infection can occur and may be associated with lethargy, convulsions, jaundice, petechiae, hepatosplenomegaly, chorioretinitis, and pulmonary infiltrates. Survivors may exhibit various degrees of neurologic impairment. Fetal infection can occur after primary or reactivated maternal infections, with primary infections carrying a much higher risk. Severe, generalized disease can occur in immunocompromised patients and often is associated with severe end-organ disease, such as colitis, esophagitis, pneumonitis, retinitis, and adrenalitis. Retinitis caused by CMV was the most common cause of blindness among people with AIDS in the era before highly active antiretroviral therapy, but its incidence has fallen precipitously. CMV can cause a polyradiculopathy and other, less common neurologic manifestations in patients with AIDS or other conditions of immunocompromise. Therapy with ganciclovir and foscarnet is indicated, but treatment results may be disappointing.

Diagnostic Strategies and Differential Considerations.: Mononucleosis caused by CMV may be clinically indistinguishable from syndromes caused by EBV or Toxoplasma. In the perinatal period, infants with generalized infections require evaluation for other common perinatal infections, such as toxoplasmosis, rubella, syphilis, and HSV infection. Recipients of organ transplants and other immunocompromised patients with fever and other signs and symptoms of generalized infection require intensive evaluation for bacterial and viral causes of infection. Diagnosis of CMV infection depends on viral isolation, detection of CMV pp65 antigen, or the demonstration of a fourfold rise in antibody to viral antigens.

Management.: Only supportive care is indicated for infected immunocompetent adults and children, and they generally can be managed at home. CMV infection in the perinatal period or complicated by impairment of immune function can be life-threatening, and patients in whom such infections are suspected generally require hospitalization for aggressive evaluation, monitoring, and specialized care. Valganciclovir, ganciclovir, foscarnet, and cidofovir are useful in treatment of CMV infections in immunocompromised patients.

Viral Infections Presenting as Nonspecific Febrile Disease

Coxsackieviruses, Echoviruses, and Other Enteroviruses:

Principles of Disease.: The enteroviruses are spread from person to person by the fecal-oral route. As with poliovirus, inapparent infections greatly outnumber symptomatic cases.

Clinical Features.: Most enteroviral infections are inapparent. The most common clinical presentation is that of a nonspecific febrile illness. Young children may be hospitalized with enteroviral fevers that simulate bacterial sepsis. Coxsackievirus B and some of the echoviruses may cause severe perinatal infection associated with fever, meningitis, myocarditis, and hepatitis.

Differential Considerations.: Other proven or suggested associations of the enteroviruses and disease include enterovirus 70 with acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis, Coxsackieviruses and echoviruses with diarrhea and gastroenteritis, Coxsackieviruses and echoviruses with hemolytic-uremic syndrome, and enteroviruses with acute myositis. Other possible associations include chronic cardiomyopathy, aortitis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, orchitis, diabetes mellitus, lymphadenopathy, a mononucleosis-like syndrome, and infectious lymphocytosis. A progressive, dementing, chronic meningitis associated with enteroviruses has been reported in persons with common variable immunodeficiency syndromes.

Principles of Disease.: Colorado tick fever, or mountain fever, is caused by a coltivirus similar to the orbiviruses that are transmitted to humans through the bite of the hard-shelled wood tick Dermacentor andersoni. It occurs primarily in the western United States, but a serotype has been isolated from the Ixodes ricinus tick in Germany and from the dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis, in Long Island, New York. Illness generally occurs in late spring through summer (see Chapter 134).

Clinical Features.: The incubation period for Colorado tick fever is 3 to 6 days, and a history of tick exposure is elicited in 90% of patients. The disease generally occurs in people engaged in activities that bring them into contact with ticks. The fever is biphasic, as indicated by a “saddle-back” curve plotting temperatures over time, with the patient initially acutely experiencing chills, lethargy, prostration, headache, ocular pain, photophobia, abdominal pain, and severe myalgias. The initial fever lasts 2 to 3 days, recedes for a similar period, and then is followed by a second fever lasting approximately 3 days. Rash, occasionally petechial, is uncommon, occurring in 5 to 10% of patients. Meningoencephalitis is a rare but serious complication in children. Convalescence lasts 1 to 3 weeks; half of infected persons are viremic 4 weeks after the onset of illness.68

Differential Considerations.: Colorado tick fever commonly is misdiagnosed as Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Patients with fever and rash after tick bites in endemic areas should be treated for Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Confirmation of the diagnosis of Colorado tick fever is by mouse inoculation or fluorescent staining of erythrocytes.

Orbivirus.: Six orbiviruses have been implicated in human disease. Changuinola virus is transmitted from Phlebotomus flies; Lebombo and Orungo viruses from mosquitoes; and Kemerovo, Lipovnik, and Tribec viruses from ticks. All six have been associated with febrile illnesses and, rarely, encephalitis.

Viruses Associated with Respiratory Infections

Principles of Disease.: Rhinoviruses are the most common cause of the common cold. More than 100 strains exist. Rhinovirus transmission generally occurs primarily by hand contact and through inoculation of the eye or nasal mucosa and less commonly by aerosolization of respiratory secretions. Viral replication probably occurs on the epithelial surface of the nasal mucosa.

Clinical Features.: After a 1- to 4-day incubation period, the usual signs and symptoms of rhinoviral infection occur, including nasal obstruction, sneezing, sore throat, cough, and malaise. Severe tracheobronchitis and pneumonia occur rarely. Fever and lower respiratory tract infections are more common in children than in adults with rhinovirus infections.

Differential Considerations.: Other respiratory pathogens, such as coronaviruses, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), parainfluenza viruses, influenza viruses, adenoviruses, and enteroviruses, can produce clinical syndromes similar to those produced by the rhinoviruses. The rhinoviruses in general cause less morbidity than that typical for the parainfluenza viruses and RSV.

Diagnostic Strategies.: Definitive diagnosis is made by the demonstration of a rise in antibody titer. New commercially available molecular assays include detection of rhinovirus in their viral panel.69

Management.: Treatment is aimed at relief of symptoms. Routine vaccination appears to be an unlikely prospect because of the number of serotypes. Because hand-to-face inoculation appears to be the predominant means of transmission, frequent handwashing during epidemic periods may decrease the spread of rhinovirus infections.

Principles of Disease.: Adenoviruses are the most clinically important viruses because of their capacity to cause upper respiratory tract infections, conjunctivitis, and gastroenteritis. Nevertheless, no drugs or therapeutic measures specifically effective for adenoviral infections are available. Adenovirus is used as a vector in many vaccines that are being studied against viral pathogens (including rotavirus, hepatitis B, RSV, HIV, and Ebola), a growing area of vaccine research.

Clinical Features.: Adenoviruses cause respiratory diseases ranging from pharyngitis and tracheitis to fulminant bronchiolitis and pneumonia. Cough, fever, sore throat, and rhinorrhea are the most common symptoms and generally last only a few days. Pneumonitis with interstitial infiltrates is occasionally seen with some strains. Upper respiratory findings may be associated with conjunctivitis (pharyngoconjunctival fever). Adenoviruses may cause an epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, which in severe cases may be associated with conjunctival scarring. Other syndromes associated with adenoviruses include hemorrhagic cystitis, infantile diarrhea, intussusception, encephalitis, and meningoencephalitis.

Differential Considerations.: Other pathogens causing similar atypical pneumonia syndromes include influenza and parainfluenza viruses and Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Diarrheal syndromes may be similar to those caused by rotaviruses.

Coronaviridae

Principles of Disease.: The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was first documented in China’s Guangdong province in November 2002. By the time the epidemic was contained in July 2003, it had affected approximately 8000 persons in 29 countries, with a case fatality rate of approximately 10%.70 The causative agent was identified as a novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV).71,72 Early in the epidemic, astute researchers noted that the illness was more prevalent among restaurant workers and focused attention on live animals that were being sold for human consumption. Their efforts revealed that the virus was transmitted to humans by handling and consumption of wild mammals, such as the civet.73

By 2003, 161 cases of SARS had been reported in the United States, but no deaths were reported that were attributable to SARS.70 Most patients had traveled to an area of documented or suspected SARS transmission.

Clinical Features.: The current CDC case definition for SARS-CoV disease includes the presence of laboratory-confirmed infection or severe respiratory illness in the setting of epidemiologic criteria for likely exposure to SARS-CoV.70 Early disease is defined by the presence of two or more of the following features: fever (which may be subjective), chills, rigors, myalgia, headache, diarrhea, sore throat, and rhinorrhea. Mild to moderate disease requires presence of fever with temperature higher than 38° C and evidence of lower respiratory tract illness. Severe respiratory illness is defined as noted previously but also includes radiographic evidence of pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome.74 Laboratory diagnosis of the disease relies on SARS-CoV antibody testing, cell culture, or reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) techniques. Epidemiologic criteria for possible exposure include travel within the past 10 days to an area with documented or suspected recent transmission of SARS-CoV or close contact with a symptomatic person who recently engaged in such travel. Epidemiologic criteria for likely exposure require that transmission be somehow linked to a person with confirmed disease.75

Retrospective analyses of the SARS-CoV infection outbreak suggest an incubation period of 3 to 10 days with an ensuing viral prodrome characterized by headache, malaise, and myalgias. Fever, clinical evidence of upper and lower respiratory infection, dyspnea, and gastrointestinal disturbances also may be features. Chest radiographs are normal in appearance in up to 25% of patients with early infection, despite the presence of fever and respiratory complaints. CT scans may be more useful in identifying early pulmonary involvement. Hypoxemia, with clinical and radiographic evidence of pneumonitis, develops as the disease progresses. In a minority of patients, progressive respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome may follow. Patients older than 60 years and those with comorbid illness, such as diabetes mellitus, have worse outcomes.74–76 A Hong Kong study reported reliable results when diagnostic criteria were combined with variables including exposure, history, and laboratory findings.77

Diagnostic Strategies.: Laboratory findings are nonspecific but include lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, and prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time. Hemolytic anemia and electrolyte disturbances, such as severe hypomagnesemia with associated tetany, have been reported.78 Serologic testing for antibody to SARS-CoV is most reliable if it is performed more than 21 days after infection, and PCR analysis may be negative early in the course of illness.

Differential Considerations.: The clinical features of SARS-CoV mimic those of many community and nosocomial respiratory infections, so the differential diagnosis is broad in scope. The initial workup should include routine laboratory and radiographic evaluations similar to those for other, more common respiratory infections. A greater level of suspicion for SARS-CoV infection should be entertained on the basis of travel or exposure history. Specific testing for coronavirus can be conducted through the health department.

Several outbreaks of SARS-CoV infection have occurred after exposure of patients or medical staff to a sentinel case or to a clinical specimen.79 Therefore, effective evaluation and management of suspected or proven cases of SARS-CoV disease should begin with a travel and occupational history, astute clinical observation, appropriate triaging, and patient isolation measures. Quarantine of persons who may be in the incubation period has proved useful in containing outbreaks.80 Contact and airborne precautions should be instituted, and protective eyewear should be considered. Detailed guidelines for the diagnosis, isolation, treatment, and disposition of patients with suspected or proven SARS-CoV infection are continually being updated by the WHO and the CDC. These guidelines are available at www.cdc.gov and www.who.int; local health officials also can be contacted for guidance.

Management.: No therapeutic measures beyond supportive care have been shown to be clearly effective for the treatment of SARS-CoV infection. Patients with signs and symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection should be treated with conventional antibiotic and supportive therapy, even if they are suspected of having SARS-CoV infection.

Disposition.: It is not necessary to hospitalize all patients who are thought to have been exposed to or to have a respiratory syndrome that could be attributed to SARS-CoV infection. Persons well enough to be cared for at home should be placed in home quarantine with contact and airborne precautions. Termination of quarantine precautions for suspected SARS-CoV infection should be done in consultation with public health officials. Infection control is of the utmost importance, given the increased risk to health care workers and of nosocomial transmission; particular care must be paid to procedures at high risk for aerosolization of the virus, including intubation and nebulization.80,81 Expert consultation from an infectious disease specialist and public health authorities is recommended.

Principles of Disease.: Coronaviruses are agents of the common cold in adults and of lower respiratory tract disease in children. More commonly causing epidemic diarrheal disease in pigs and cows, they have recently been implicated in diarrheal disease in children.

Clinical Features.: Coronaviruses primarily cause upper respiratory tract disease in adults. Lower respiratory tract infections caused by coronaviruses occur uncommonly in adults and more commonly in children. They appear to cause diarrheal disease in children younger than 1 year.

Differential Considerations.: Coronaviruses probably account for 15% of adult colds. Rhinoviruses account for most of the rest, with parainfluenza viruses, influenza viruses, RSVs, adenoviruses, and enteroviruses also causing upper respiratory infections and colds. Rotaviruses, Norwalk viruses, and enteroviruses cause most viral cases of gastroenteritis in children.

Paramyxoviridae

Clinical Features.: The parainfluenza viruses are the most common causes of croup in children and, along with RSV, are the most common causes of lower respiratory tract infections that require hospitalization in infants.

Differential Considerations.: Viruses causing upper respiratory tract infection similar to that caused by the parainfluenza viruses include adenoviruses, rhinoviruses, influenza virus, RSV, echoviruses, Coxsackieviruses, and coronaviruses. Identification of parainfluenza viral infection can be made by demonstrating a fourfold rise in antibody titer between acute and convalescent serum.

Management.: Croup may be worse at night; mist inhalation often is helpful. Nebulized racemic epinephrine can be used to treat severe croup, but the relief it affords can be short-lived, and return to pretreatment state can be seen within 2 hours of therapy. Intramuscular steroids have been shown to be helpful, and their use has been associated with a decreased requirement for hospitalization of children with croup.82 A single dose of oral dexamethasone at 0.6 mg/kg has been shown to reduce return visits to a health care practitioner.83 The parainfluenza viruses can cause reinfection within months of the primary infection, so prevention of infection is unlikely to be feasible. More aggressive tracheal diseases, such as laryngotracheobronchitis and laryngotracheobronchopneumonitis, may be caused by viruses, but most are often a result of superinfection with bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus and group A streptococci.84

Orthomyxoviridae

Principles of Disease.: Influenza generally is a self-limited infection of the upper respiratory tract associated with fever, cough, coryza, sore throat, and malaise. Three types of influenza are recognized. Type A has been associated with most widespread epidemics and pandemics and is associated with most of the deaths caused by influenza. Influenza B causes regional or widespread epidemics every 2 to 3 years. Influenza C is associated with sporadic cases.85

Clinical Features.: The usual clinical disease caused by influenza begins 1 to 4 days after exposure to aerosol respiratory secretions. Clinical manifestations include fever accompanied by myalgias, coryza, conjunctivitis, headache, and nonproductive cough. Patchy infiltrates can be seen on the chest radiograph. Signs and symptoms generally last only a few days, but fatigue and malaise may persist for weeks. The most common serious complications of influenza, particularly among elders and persons with chronic diseases, are pneumonia caused by influenza itself and pneumonia attributable to secondary bacterial infections. More than 90% of deaths during seasonal epidemics are due to exacerbation of cardiopulmonary disease in elders.85 Rare complications of influenza infection include aseptic meningitis, pericarditis, and a postinfectious neuritis that resembles the Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Diagnostic Strategies.: Viral culture remains the “gold standard” modality for the laboratory diagnosis of influenza, but results often are not timely enough to aid in clinical decisions for therapy. Several rapid assays using nasal specimens for the diagnosis of influenza A or B are commercially available. Rapid influenza diagnostic tests are direct antigen tests that provide results in less than 30 minutes. Some can distinguish between type A and B viruses; however, their sensitivity varies from 10 to 70% and may be greater in children and during the first 48 hours of illness when viral shedding is highest.86 Positive bedside test results are associated with increased use of antivirals and decreased use of antibiotics in both pediatric and adult patients87,88; however, because of their low sensitivity, they are best used for screening and for “ruling in” disease, but they cannot reliably exclude influenza in a patient presenting with influenza-like illness.89 Therefore, clinical decisions should be based on clinical suspicion of influenza-like illness. Real-time PCR assays are now available for confirmation of influenza, with enhanced sensitivity and specificity and the capability of specific influenza type detection, including novel H1N1.90

Differential Considerations.: The syndromes produced by the influenza viruses overlap with those produced by other viruses, such as the parainfluenza viruses, RSV, adenoviruses, coronaviruses, and echoviruses.

Management.: General supportive measures will ameliorate the symptoms of influenza. The neuraminidase inhibitors zanamivir and oseltamivir have been approved for treatment of both influenza A and B. The dose of oseltamivir should be decreased to 75 mg once daily in patients with creatinine clearance less than 30 mL/min. Zanamivir or oseltamivir should be administered within 2 days of onset of symptoms if efficacy is to be expected.16 Vaccination is recommended yearly for all children 6 months to 5 years of age, adults older than 50 years, and persons at high risk for significant morbidity or death from influenza; these include immunosuppressed patients, those with chronic illnesses, and pregnant women. Vaccination is also recommended for health care workers and persons who are household contacts of infected persons younger than 5 years or older than 50 years. In addition, the CDC recommends annual vaccination for all persons “who want to reduce the risk of becoming ill with influenza or of transmitting influenza to others.” Aspirin and aspirin-containing products should be avoided, especially among children and adolescents, particularly during influenza epidemics, because of the association between the use of aspirin during a bout of influenza and the subsequent development of Reye’s syndrome.52