Viral Hepatitis

At the conclusion of this chapter, the reader should be able to:

• Identify and describe the characteristics of the various forms of primary infectious hepatitis, including laboratory assays.

• Compare the etiology, epidemiology, signs and symptoms, laboratory evaluation, and prevention of the various types of hepatitis.

• Analyze case studies related to the immune response various forms of hepatitis.

• Correctly answer case study related multiple choice questions.

• Be prepared to participate in a discussion of critical thinking questions.

• Describe the principle, results, and limitations of the rapid HCV test.

General Characteristics of Hepatitis

Incidence

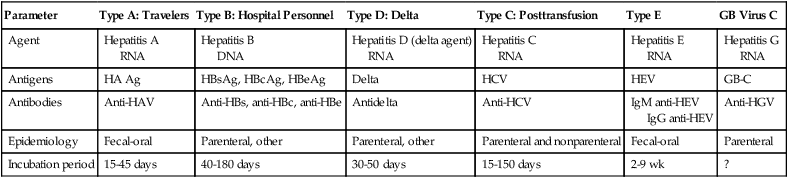

Primary hepatitis viruses account for approximately 95% of the cases of hepatitis. These viruses are classified as primary hepatitis viruses because they attack primarily the liver and have little direct effect on other organ systems. The secondary viruses involve the liver secondarily in the course of systemic infection of another body system. The viruses for hepatitis types A, B, C, D, E, and GB virus C, as well as secondary viruses (e.g., EBV, CMV), have been isolated and identified (Table 23-1).

Table 23-1

Characteristics of Viral Hepatitis

| Parameter | Type A: Travelers | Type B: Hospital Personnel | Type D: Delta | Type C: Posttransfusion | Type E | GB Virus C |

| Agent | Hepatitis A RNA |

Hepatitis B DNA |

Hepatitis D (delta agent) RNA |

Hepatitis C RNA |

Hepatitis E RNA |

Hepatitis G RNA |

| Antigens | HA Ag | HBsAg, HBcAg, HBeAg | Delta | HCV | HEV | GB-C |

| Antibodies | Anti-HAV | Anti-HBs, anti-HBc, anti-HBe | Antidelta | Anti-HCV | IgM anti-HEV IgG anti-HEV |

Anti-HGV |

| Epidemiology | Fecal-oral | Parenteral, other | Parenteral, other | Parenteral and nonparenteral | Fecal-oral | Parenteral |

| Incubation period | 15-45 days | 40-180 days | 30-50 days | 15-150 days | 2-9 wk | ? |

Signs and Symptoms

As a clinical disease, hepatitis can occur in acute or chronic forms. The signs and symptoms of hepatitis are extremely variable. It can be mild, transient, and completely asymptomatic or it can be severe, prolonged, and ultimately fatal. Many fatalities are attributed to hepatocellular carcinoma in which hepatitis viruses B and C are the primary causes. The course of viral hepatitis can take one of four forms—acute, fulminant acute, subclinical without jaundice, and chronic (Table 23-2).

Table 23-2

| Form | Characteristics |

| Acute hepatitis | Typical form with associated jaundice. Four phases—incubation, preicteric, icteric, and convalescence Incubation period, from time of exposure and first day of symptoms, ranges from few days to many months Average length of time is 75 days (range, 40-180) in hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection |

| Fulminant acute hepatitis | Rare form of hepatitis associated with hepatic failure |

| Subclinical hepatitis without jaundice | Probably accounts for persons with demonstrable antibodies in their serum but no reported history of hepatitis |

| Chronic hepatitis | Accompanied by hepatic inflammation and necrosis that lasts for at least 6 mo Occurs in about 10% of patients with HBV infection |

Hepatitis A

Etiology

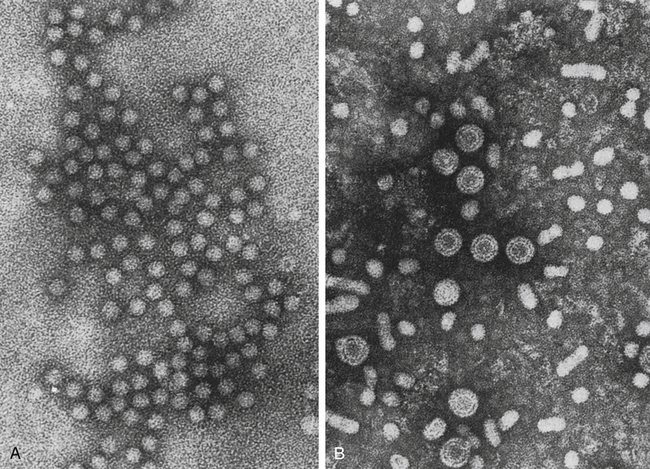

HAV is a small, RNA-containing picornavirus and the only hepatitis virus that has been successfully grown in culture (Fig. 23-1, A). The structure is a simple nonenveloped virus with a nucleocapsid designated as the hepatitis A (HA) antigen (HA Ag). Inside the capsid is a single molecule of single-stranded ribonucleic acid (RNA). The RNA has a positive polarity and proteins are translated directly from the RNA. Replication of HAV appears to be limited to the cytoplasm of the hepatocyte.

A, Hepatitis A virus (HAV). B, Hepatitis B virus (HBV). Note Dane particles. (From Katz SL, Gershon AA, Wilfert CM, Krugman S, editors: Infectious diseases of children, ed 9, St Louis, 1992, Mosby.)

Epidemiology

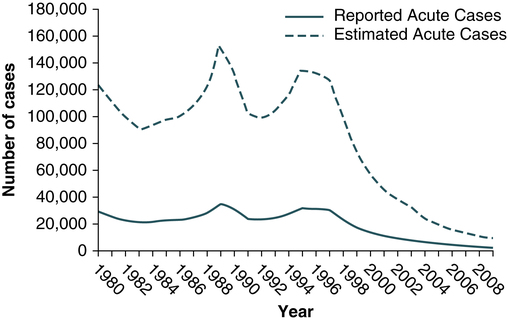

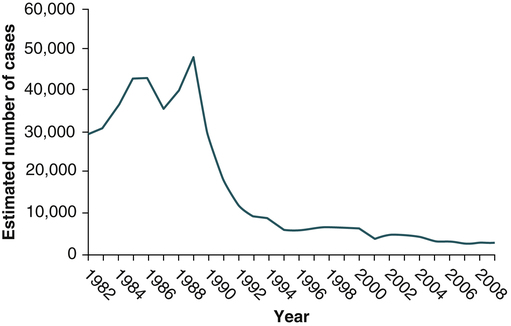

Hepatitis A virus was formerly called infectious hepatitis or short-incubation hepatitis. In developing countries, hepatitis A is primarily a disease of young children; the prevalence of infection, as measured by the presence of antibody (immunoglobulin G [IgG] anti-HAV), approaches 100% at or shortly after 5 years of age. The national rate of hepatitis A has declined steadily since the last peak in 1995 (Fig. 23-2). After asymptomatic infection and underreporting were taken into account, an estimated 21,000 new infections occurred in 2009 (the last year for which statistics were available at the time of publication).

Prevention and Treatment

A safe, highly immunogenic, formalin-inactivated, single-dose vaccine is available to prevent HAV infection (Box 23-1). HAV vaccine should be targeted at high-risk groups (e.g., staff in child care centers; food handlers; international travelers, including military personnel; homosexual men; institutionalized patients).

Hepatitis B

Etiology

HBV is the classic example of a virus acquired through blood transfusion. It serves as a model when transfusion-transmitted viral infections are considered (see Fig. 23-1, B).

2. A structural nucleocapsid core protein—hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg)

3. A soluble nucleocapsid protein—hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)

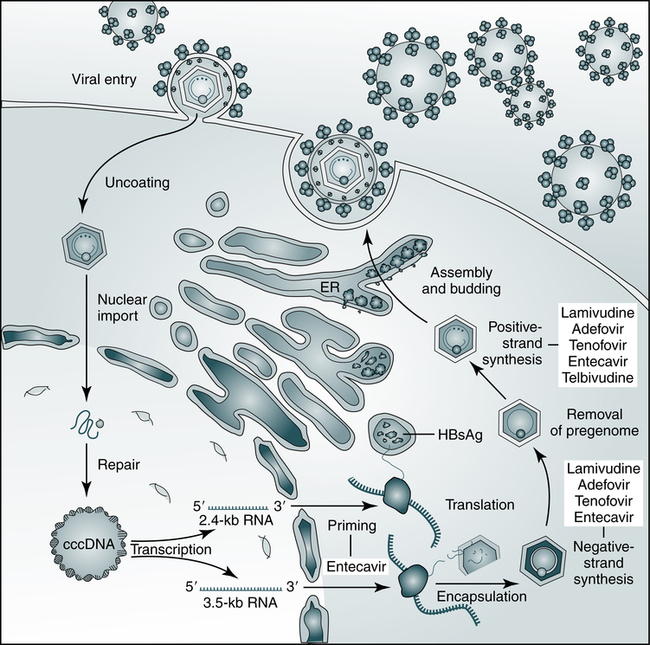

HBV relies on a retroviral replication strategy (reverse transcription from RNA to DNA). Eradication of HBV infection is rendered difficult because stable, long-enduring, covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) becomes established in hepatocyte nuclei and HBV DNA become integrated into the host genome (Fig. 23-3).

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) establishes covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) as a durable miniature chromosome in the host nucleus and relies on a retroviral strategy of reverse transcription from RNA to negative-strand DNA. The steps of HBV replication targeted by nucleoside and nucleotide analogues that are used to treat chronic HBV infection are shown. ER, Endoplasmic reticulum; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen. (From Dienstag JL: Hepatitis B virus infection, N Engl J Med 359:1486–1500, 2008.)

Epidemiology

Hepatitis B infection has been referred to as long-incubation hepatitis. In 2009 (the last year for which statistics were available at the time of publication), a total of 3371 acute symptomatic cases and 38,000 estimated total new infections of hepatitis B were reported in the United States. The overall incidence was the lowest ever recorded and represents a decline of 81% since 1990 (Fig. 23-4).

The incidence of HBV infection caused by blood transfusion is increasingly rare in developed countries. Transfusion-acquired HBV has been severely reduced because high-risk donor groups (e.g., paid donors, prison inmates, military recruits) have been eliminated as major sources of donated blood and because specific serologic screening procedures have been instituted. This shift to an all-volunteer donor supply probably accounts for a 50% to 60% reduction of transfusion-related hepatitis. The overall incidence of HBV is high among patients who have received multiple transfusions or blood components prepared from multiple-donor plasma pools, hemodialysis patients, drug addicts, and medical personnel (see Table 23-1).

• Homosexual men with multiple partners

• Household contacts and sexual partners of HBV carriers

• Infants born to HBV-infected mothers

• Patients and staff in custodial institutions for developmentally disabled persons

• Recipients of certain plasma-derived products, including patients with congenital coagulation defects

• Health care and public safety workers who may be in contact with infected blood

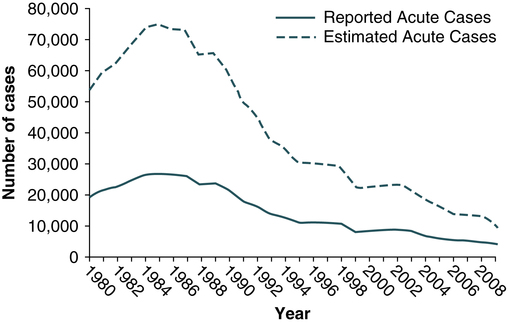

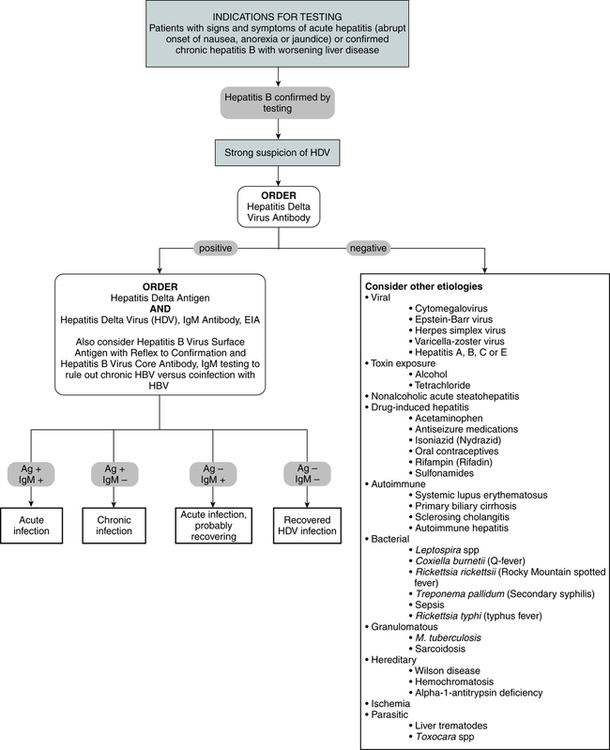

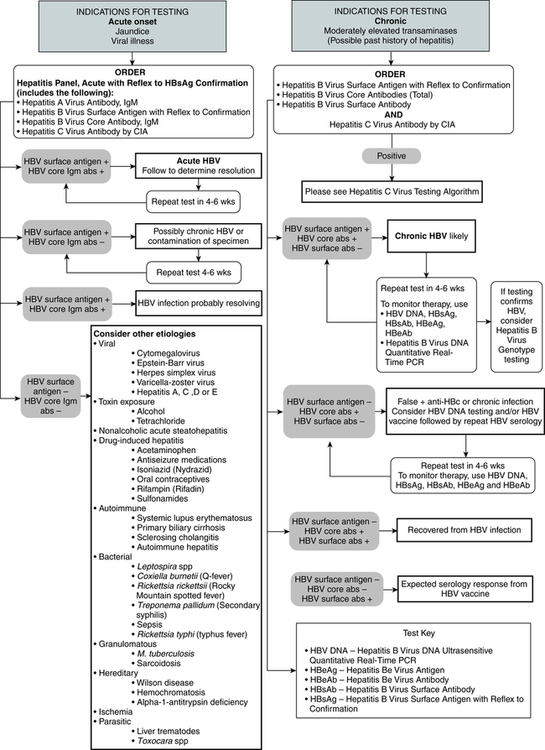

Laboratory Assays

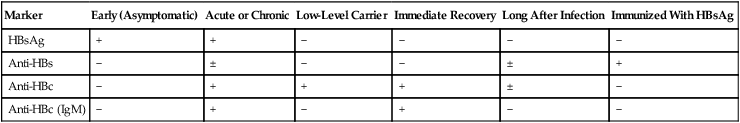

Laboratory diagnosis (Fig. 23-5) and monitoring of acute and chronic HBV infections involve the use of several of the following tests (Tables 23-3 and 23-4):

Table 23-3

Serologic Markers for Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection

| Marker | Early (Asymptomatic) | Acute or Chronic | Low-Level Carrier | Immediate Recovery | Long After Infection | Immunized With HBsAg |

| HBsAg | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Anti-HBs | − | ± | − | − | ± | + |

| Anti-HBc | − | + | + | + | ± | − |

| Anti-HBc (IgM) | − | + | − | + | − | − |

−, Negative; +, positive; ±, questionable.

Adapted from Hoofnagle JH: Type A and type B hepatitis, Lab Med 14(11):713 1983.

Table 23-4

Interpretation of Hepatitis B Panel

| Tests | Results | Interpretation |

| HBsAg Anti-HBc Anti-HBs |

Negative Negative Negative |

Susceptible |

| HBsAg Anti-HBc Anti-HBs |

Negative Positive Positive |

Immune because of natural infection |

| HBsAg Anti-HBc Anti-HBs |

Negative Negative Positive |

Immune because of hepatitis B vaccination Acutely infected |

| HBsAg Anti-HBc IgM anti-HBc Anti-HBs |

Positive Positive Negative Negative |

Chronically infected |

| HBsAg Anti-HBc Anti-HBs |

Negative Positive Negative |

Four interpretations possible∗ |

1.Might be recovering from acute HBV infection.

2.Might be distantly immune and test not sensitive enough to detect very low level of anti-HBs in serum.

3.Might be susceptible with a false-positive anti-HBc.

4.Might be undetectable level of HBsAg present in the serum and the person is actually chronically infected.

1. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

2. Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)

3. Hepatitis B core antibody, total or IgM (anti-HBc)

4. Hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe)

5. Hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs)

6. Hepatitis B viral DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR, qualitative and quantitative)

Hepatitis B Surface Antigen

The titer of HBsAg rises and generally peaks at or shortly after the onset of elevated liver serum enzyme levels (e.g., ALT, SGPT). Clinical improvement of the patient’s condition and a decrease in serum enzyme concentrations are paralleled by a fall in the titer of HBsAg, which subsequently disappears. There is variability in the duration of HBsAg positivity and in the relationship between clinical recovery and the disappearance of HBsAg (Fig. 23-6). About 5% of positive HBsAg values are false-positive results.

Differentiating Acute and Chronic Hepatitis and the Chronic Carrier State

Acute Infection

Carrier State

• The more frequently identified carriers have anti-HBe in their serum and are at a later stage of infection.

• Anti-HBe carriers are less infectious but may transmit infection through blood transfusion.

• HBsAg-positive carriers will become anti-HBe–positive carriers at a rate of about 5% to 10%/year.

• All HBsAg-positive individuals must be excluded from giving blood for transfusion.

• About one in four carriers has HBeAg in their serum. It is likely that these individuals have recently become carriers and that their blood is highly infectious.

• Patients with HBeAg-negative chronic HBV infection, in which precore or core promoter gene mutations preclude or reduce the synthesis of HBeAg, accounts for an increasing proportion of cases. These patients tend to have progressive liver injury, fluctuating liver enzyme activity, and lower levels of HBV DNA than patients with HBeAg-reactive HBV infection.

Prevention and Treatment

The use of recombinant vaccine against hepatitis B, licensed in 1982, is warranted for high-risk persons, including medical personnel (Box 23-1). HBV vaccine is administered in three doses over 7 months and is about 80% to 95% effective. The vaccine is now included in the childhood vaccination schedule. Hepatitis B vaccine is also a vaccine against cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma). Vaccination offers a new approach to preventing transfusion-acquired HBV and the dependent hepatitis D virus (HDV) in patients who are likely to need ongoing transfusion therapy, such as nonimmune patients with hemophilia, sickle cell anemia, or aplastic anemia.

Hepatitis D

Etiology

The hepatitis D virus (HDV), initially called the delta agent and then the hepatitis delta virus, was first described in 1977 as a pathogen that superinfects some patients already infected with HBV (see Table 23-1). Persons with acute or chronic HBV infection, as demonstrated by serum HBsAg, can be infected with HDV. HBV is required as a so-called helper to initiate infection.

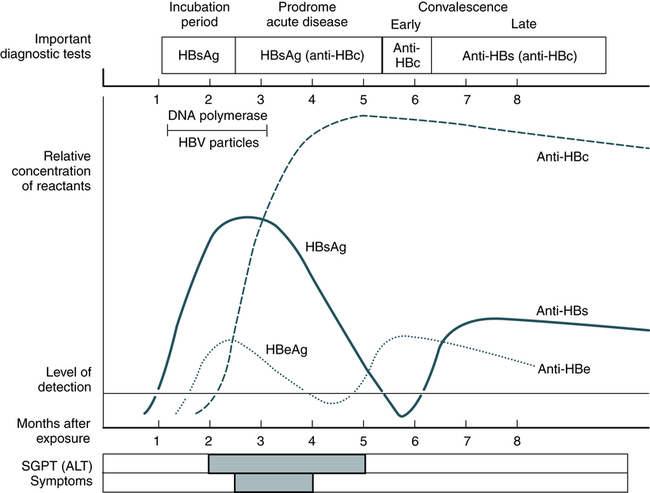

Diagnostic Evaluation

The HDV appears in the circulating blood as a particle with a core of delta antigen and a surface component of HBsAg. A person with hepatitis D will have detectable antigen in the liver and antibody in the serum. Test methodologies for HDV use the qualitative EIA (Fig. 23-7)

Hepatitis C

Etiology

Epidemiology

In the past, hepatitis C was considered a disease limited to transfusion recipients. HCV is now recognized in many other epidemiologic settings (see Table 23-1) and as a major cause of chronic hepatitis worldwide. The number of cases reported to the National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System are considered unreliable because of the following: (1) the lack of a serologic marker for acute infection; and (2) the inability of most health departments to determine whether a positive laboratory result for HCV represents acute infection, chronic infection, repeated testing of a person previously reported, or a false-positive result.

In 2009, the total number of reported cases of acute hepatitis was 2600. The estimated total number of new cases of hepatitis C in the United States was 16,000 in 2009 (the last year for which statistics were available at the time of publication). Since the mid-1990s, hepatitis C rates have declined in all age groups, almost reaching a plateau since 2003 (Fig. 23-8). The greatest decline has occurred among persons 25 to 39 years old, the age group traditionally with the highest rates of disease, in whom incidence has declined by 58% since 2000.

Viral Transmission

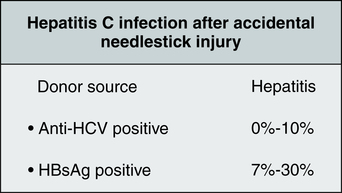

Parenteral and Occupational Exposure

In 2006, illegal IV drug use continued to be the most frequently identified risk factor for HCV infection. Accidental needlestick injuries also are a clearly documented route of hepatitis transmission (Fig. 23-9). The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has estimated that the general risk to health care workers of occupational transmission of HCV is 20 to 40 times higher than the risk of contracting HIV. The CDC has more conservatively estimated that the average risk of HCV transmission after a needlestick injury is six times greater than the risk of HIV transmission. Because of these grim statistics, occupationally acquired HCV infection is a growing concern for health care providers.

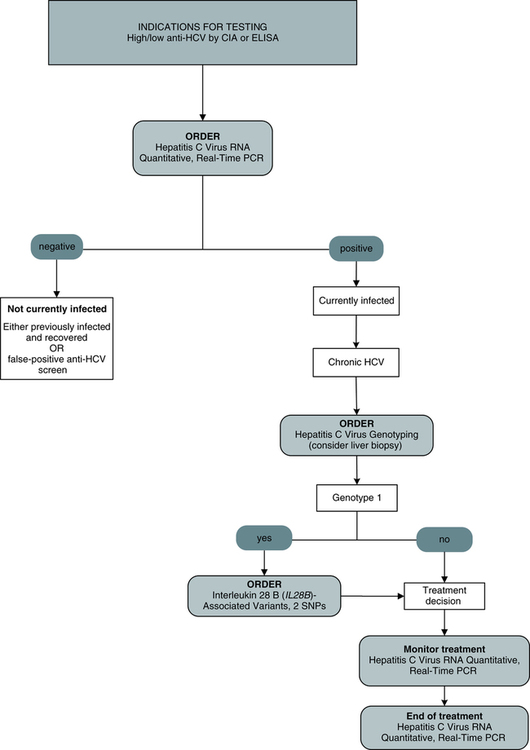

Traditional Hepatitis C Virus Testing

Traditional testing methods (Fig. 23-10) include a qualitative chemiluminescent immunoassay and qualitative EIA, qualitative recombinant immunoblot assay, quantitative real-time PCR assay, qualitative PCR assay, quantitative branched chain DNA test, polymerase chain reaction–nucleic acid sequencing. interleukin 28 B (IL-28B)–associated variants test, and two single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) method—qualitative PCR–qualitative fluorescence monitoring.

Polymerase Chain Reaction

Testing for HCV RNA by a PCR assay is particularly useful in the following situations:

Hepatitis G

Etiology

Epidemiology

Hepatitis G virus is a bloodborne agent (Table 23-5). Transfusion recipients and IV drug abusers are at risk of infection. HGV infection frequently occurs as a coinfection with HCV. Prevalence patterns of GBV-C/HGV suggest that the virus is transmitted sexually.

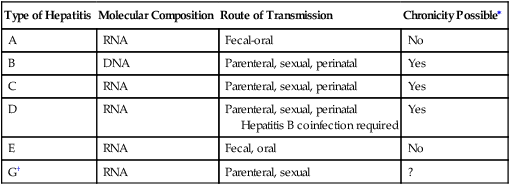

Table 23-5

Summary of Hepatitis Characteristics

| Type of Hepatitis | Molecular Composition | Route of Transmission | Chronicity Possible∗ |

| A | RNA | Fecal-oral | No |

| B | DNA | Parenteral, sexual, perinatal | Yes |

| C | RNA | Parenteral, sexual, perinatal | Yes |

| D | RNA | Parenteral, sexual, perinatal Hepatitis B coinfection required |

Yes |

| E | RNA | Fecal, oral | No |

| G† | RNA | Parenteral, sexual | ? |

Diagnostic Evaluation

A cDNA expression library was constructed from the plasma of a patient with chronic hepatitis C. Immunoscreening of the expression library with the patient’s serum identified several unique HCV and other sequences, from which an anchored PCR method (Table 23-6) was used to amplify overlapping clones for the entire viral genome. The virus was termed the GB virus C virus.

Table 23-6

Summary of Hepatitis Markers and Clinical Relationships

| Type of Hepatitis | Serum Expression or Molecular Marker | Clinical Relationship |

| Hepatitis A (HAV) | HAV RNA IgM anti-HAV IgG anti-HAV |

Direct detection of HAV in food or water samples Acute HAV Evidence of previous HAV infection |

| Hepatitis B | HBsAg HBeAg Anti-HBc (Total) Anti-HBe Anti-HBs HBV DNA |

Active hepatitis B infection Active hepatitis B infection Current or past HBV infection Recovery phase of hepatitis B Past infection—evidence of immunity Various manifestations of HBV |

| Hepatitis C | Anti-HCV HCV RNA |

Current or past HCV infections Current HCV infection |

| Hepatitis D | IgM anti-HDV IgG anti-HDV HDV RNA |

Active or chronic hepatitis D infection Chronic hepatitis D, Convalescent hepatitis D status Active HDV infection |

| Hepatitis E | IgM anti-HEV IgG anti-HEV HEV RNA |

Current/new hepatitis E infection Current/former hepatitis E infection Current hepatitis E infection |

| GB virus C | GB virus C RNA | Chronic GB virus C |

Chapter Highlights

• Viral agents of acute hepatitis can be divided into primary hepatitis viruses—A, B, C, D, E, and G—as well as secondary hepatitis viruses, including Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus, and others. Primary hepatitis viruses account for approximately 95% of the cases of hepatitis.

• As a clinical disease, hepatitis can occur in an acute or chronic form.

• Hepatitis A virus (HAV; formerly infectious or short-incubation hepatitis) is common in underdeveloped or developing countries.

• HAV is transmitted almost exclusively by a fecal-oral route during the early phase of acute illness because the virus is shed in feces for up to 4 weeks after infection occurs.

• The incidence of HAV is not increased in health care workers or dialysis patients.

• Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the classic example of a virus acquired through blood transfusion. Reported cases of acute hepatitis B have decreased dramatically in the United States in the last 15 years.

• HBV is largely spread parenterally through blood transfusion, needlestick accidents, and contaminated needles, although the virus can be transmitted in the absence of obvious parenteral exposure.

• Serologic markers for HBV infection include HBsAg, HBeAg, anti-HBc, anti-HBe, anti-HBs, and DNA analysis.

• Hepatitis D virus (HDV; initially, the delta agent) superinfects some patients already infected with HBV.

• Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is prevalent in the United States and Western Europe and resembles HBV in terms of transmission characteristics. Health care workers should avoid needlestick injuries.

• Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is transmitted by the fecal-oral route and usually is caused by poor sanitation. No form of chronic liver disease has been attributable to HEV infection. Although most acute infections are self-limited and mild, about 10% to 20% of HEV infections in pregnant women result in fulminant hepatitis, especially in the third trimester of pregnancy.

• GB virus C virus (HGV) is a bloodborne agent. Transfusion recipients and IV drug abusers are at risk of infection. HGV frequently occurs as a coinfection with HCV. HGV is estimated to produce 900 to 2000 infections/year; most are asymptomatic. Chronic disease is rare or may not occur at all.

• Transfusion-transmitted virus (TTV), a recent addition to the infectious hepatitis family. The most remarkable feature of TTV is the extraordinarily high prevalence of chronic viremia in apparently healthy people, almost 100% in some countries. As with HGV, the pathogenicity of TTV has not been proven.