Chapter 10 Vesiculobullous disorders

| INTRAEPIDERMAL BLISTERS | SUBEPIDERMAL BLISTERS |

|---|---|

Table 10-2. Acute versus Chronic Onset of Vesiculobullous Eruption

| ACUTE | CHRONIC |

|---|---|

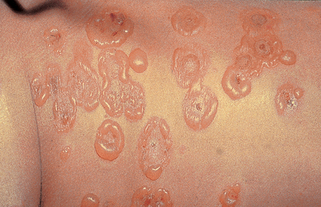

The character of the blisters also may provide useful information. Flaccid blisters may indicate a more superficial blistering process than is seen with tense blisters. However, factors other than the depth of the blister are important, including site (blisters on acral skin, which has a thick stratum corneum, are often tense even when superficial) and the specific disease process (in toxic epidermal necrolysis, the blistering is subepidermal, but vesicles and bullae are usually flaccid with large sheets of skin sloughing).

Table 10-3. Characteristic Distribution of Vesiculobullous Diseases

| DISEASE | CHARACTERISTIC DISTRIBUTION |

|---|---|

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica | Acral, periorificial |

| Allergic contact dermatitis | Reflects pattern of contact; often linear |

| Bullous dermatophyte infection | Feet, hands |

| Bullous diabeticorum | Distal extremities |

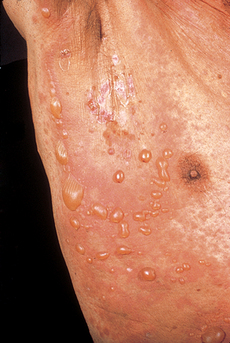

| Bullous pemphigoid | Flexural areas, lower extremities |

| Cicatricial pemphigoid | Eyes, mucous membranes |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Elbows, knees, buttocks |

| Erythema multiforme | Acral areas, palms, soles, mucosa |

| Hailey-Hailey disease | Intertriginous areas, neck |

| Hand, foot, and mouth disease | Mouth, palms, fingers, soles |

| Herpes zoster | Dermatomal distribution |

| Linear IgA bullous dermatosis (childhood type) | Groin, buttocks, perineum |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Oral mucosa, other sites |

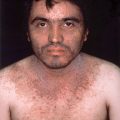

| Pemphigus foliaceus | Head, neck, trunk |

Table 10-4. Direct Immunofluorescence Findings of Vesiculobullous Diseases

| DISEASE | TARGET ANTIGEN | DIRECT IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE FINDINGS |

|---|---|---|

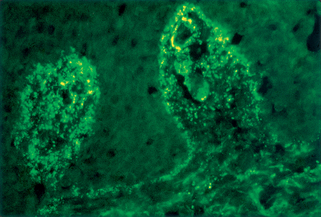

| Bullous pemphigoid | BP180, BP230 | Linear C3, IgG at DEJ |

| Bullous SLE | COL7A1 | Linear/granular IgG, other Igs at DEJ |

| Cicatricial pemphigoid | BP180, LAM5, and others | Linear C3, IgG, IgA at DEJ |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | eTG | Granular IgA, C3 in upper dermis (see Fig. 10-1) |

| Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita | COL7A1 | Linear IgG, IgA, other Igs at DEJ |

| Herpes gestationis | BP180 | Linear C3, IgG at DEJ |

| Linear IgA bullous dermatosis | BP180, COL7A1, LAD | Linear IgA, C3 at DEJ |

| Pemphigus foliaceus | DSG1 | IgG, C3 in intercellular spaces |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | DSG3 (mucous membrane only) DSG3 and DSG1 (mucous membrane and skin) |

IgG, C3 in intercellular spaces |

| IgA pemphigus | DSC1, DSG1, DSG3 | IgA in intercellular spaces |

| Paraneoplastic pemphigus | DSG1, DSG3, DP1, DP2, BP180, BP230, EP, PP, γ-catenin, plectin, 170 kD, DSC2, DSC3 | IgG, C3 in intercellular spaces, DEJ |

| Porphyria cutanea tarda | None (not antibody mediated) | Homogenous IgG at DEJ and around vessels |

| Anti–p200 pemphigoid | 200-kD antigen | IgG, C3 at DEJ |

| Anti–p105 pemphigoid | 105-kD antigen | IgG, C3 at DEJ |

DEJ, Dermal–epidermal junction; Ig, immunoglobulin; C3, third complement component.

Zillikens D: Diagnosis of autoimmune bullous skin diseases, Clin Lab 54:491–503, 2008.

| ERUPTION | OFFENDING DRUG(s) |

|---|---|

| Bullous pemphigoid | Tetracycline, furosemide, ibuprofen and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), captopril, penicillamine, and other antibiotics |

| Erythema multiforme | Anticonvulsants, barbiturates, sulfonamides, NSAIDs, antibiotics |

| Linear IgA bullous dermatosis | Vancomycin, lithium, captopril, antibiotics |

| Phototoxic drug eruption | Psoralens, thiazides, furosemide, fluoroquinolones, doxycycline (and other TCNs), sulfonamides |

| Porphyria-like drug eruption | Furosemide, tetracycline, naproxen |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens-Johnson syndrome | Anticonvulsants, sulfonamides, NSAIDs, allopurinol, antiretrovirals |

TCNs, tetracyclines.

Table 10-6. Subtypes of Epidermolysis Bullosa

| DISEASE | DEFECT | LEVEL OF SPLIT |

|---|---|---|

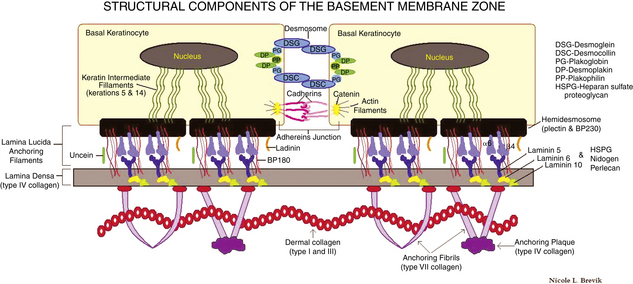

| EB simplex | Keratins 5 and 14 | Basal keratinocytes |

| EB simplex with muscular dystrophy EB simplex with pyloric atresia EB simplex, Ogna type EB simplex, Dowling-Meara type |

Plectin | Intracytoplasmic plaque of hemidesmosome |

| Junctional EB, Herlitz Junctional EB, non-Herlitz (GABEB) Junctional EB with pyloric atresia |

Laminin components α3, β3, α2 BP180 (COLXVIIa1) Laminin components α3, β3, γ2 Integrins α6, β4 |

Lamina densa/lucida interface Lamina lucida Lamina densa/lucida interface Lamina lucida/hemidesmosome |

| Dystrophic EB | Type VII Collagen (COL VIIa1) | Sublamina densa |

For all types of epidermolysis bullosa, skin biopsies for routine histology (sometimes with immunoperoxidase stains to type IV collagen to detect the level of the split), as well as electron microscopy, are often required for diagnosis. Referral to a center specializing in epidermolysis bullosa is optimal, and also the National Epidermolysis Bullosa Registry (telephone: 919-966-2007) may be contacted. The mechanobullous diseases are covered in detail in Chapter 6.

Key Points: Vesiculobullous Disorders

Lehman JS, Camilleri MJ, Gibson LE: Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita: concise review and practical considerations, Int J Dermatol 48:227–235, 2009.