Vesicles, Pustules, Bullae, Erosions, and Ulcerations

Renee M. Howard, Ilona J. Frieden

Introduction

Vesiculopustular and bullous disorders are common in the neonatal period and the first years of life. Accurate and prompt diagnosis is essential because some conditions that present with blisters and pustules are truly life-threatening. In contrast, many others are innocuous and self-limited; misdiagnosis of a more serious condition can lead to iatrogenic complications, unnecessary expense, and parental anguish.

The causes of blisters and pustules in newborns and young infants are influenced by the clinical setting, including geography and whether patients are seen in a hospital or clinic. Infection is the most common etiology in developing countries. In a study of neonates in India with blisters and pustules, bacterial infection was the most common overall, whereas erythema toxicum was the most prevalent non-infectious etiology.1 In a prospective study of newborn inpatients in California examined by pediatric dermatologists, the most common eruption in newborns was erythema toxicum.2 In a retrospective European study done in a Level 3 nursery, vesicles and pustules were the sole reason for admission to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) in 29.8% of infants admitted because of skin lesions.3

Several articles have reviewed an approach to infants with these cutaneous findings,4–6 including infants with hemorrhagic vesiculopustules.7 There is also considerable overlap with the subject matter in other chapters of this book, most notably Chapter 7 (Transient Benign Cutaneous Lesions in the Newborn), and Chapters 12, 13 and 14 (Bacterial, Viral, and Fungal Infections, respectively), so the main discussion of specific disorders are discussed therein. Chapter 11 discusses the diagnosis and management of epidermolysis bullosa and other non-infectious causes of bullae, so those conditions are covered in far less detail in this chapter.

In addition to a discussion of vesicles, pustules and bullae, this chapter also includes conditions presenting with erosions and ulcerations. Although vesicles, pustules, and bullae are primary skin lesions, they can quickly progress to secondary skin lesions (i.e. erosions and ulcerations). This can occur rapidly or have transpired in utero, such that erosions and ulcerations are the main presenting finding. Examples include staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, where erythema and skin erosions predominate over blisters, and Pseudomonas skin infection, where pustules rapidly evolve into necrotic ulcers.

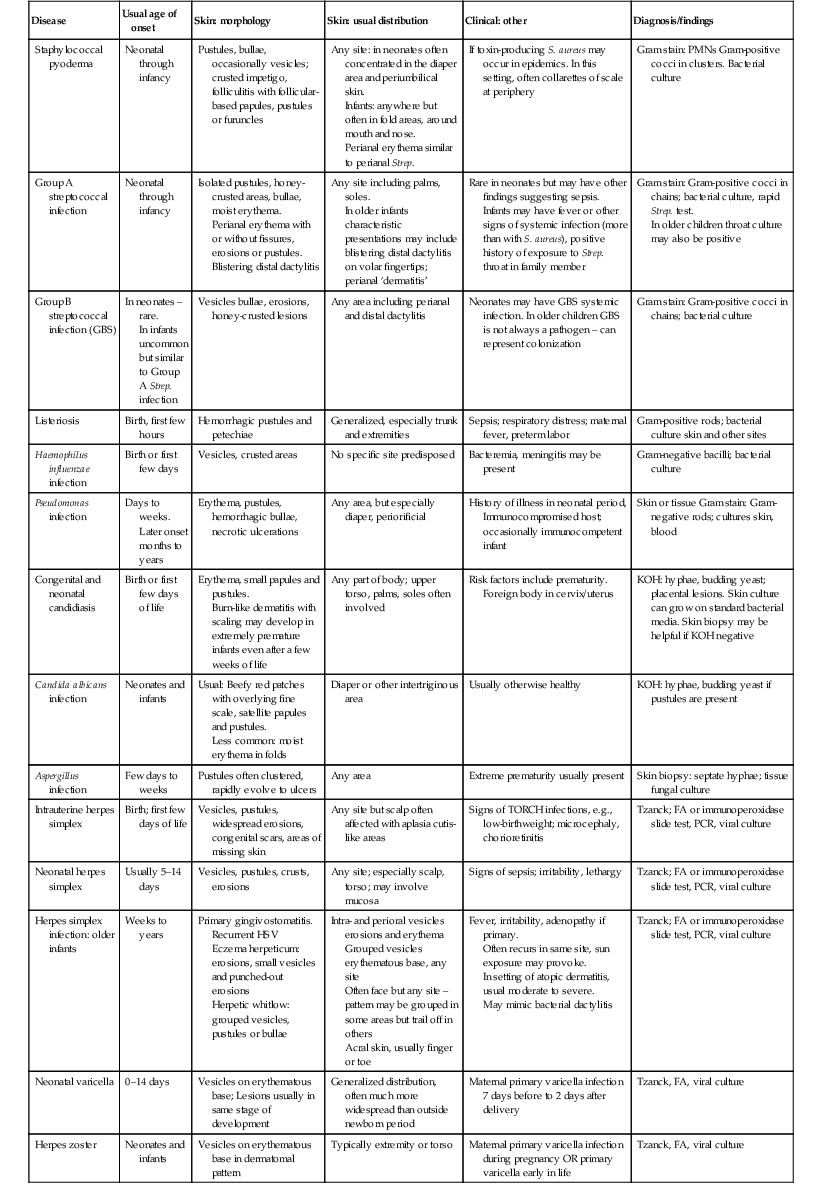

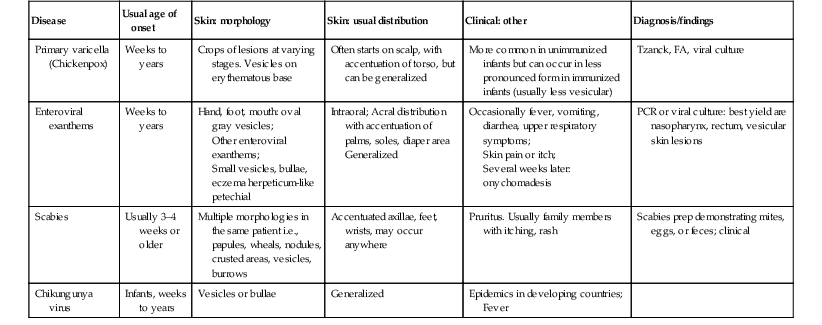

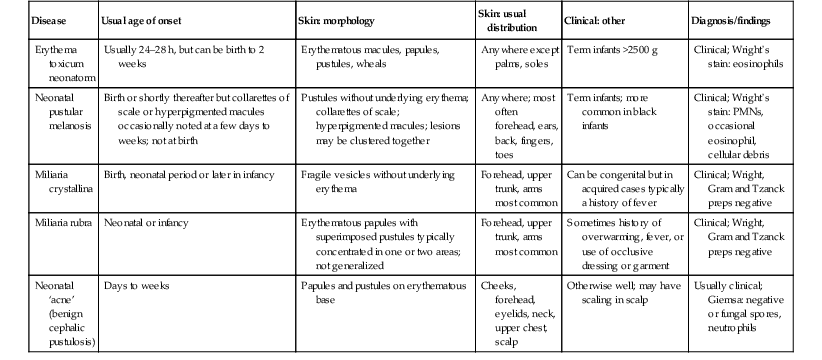

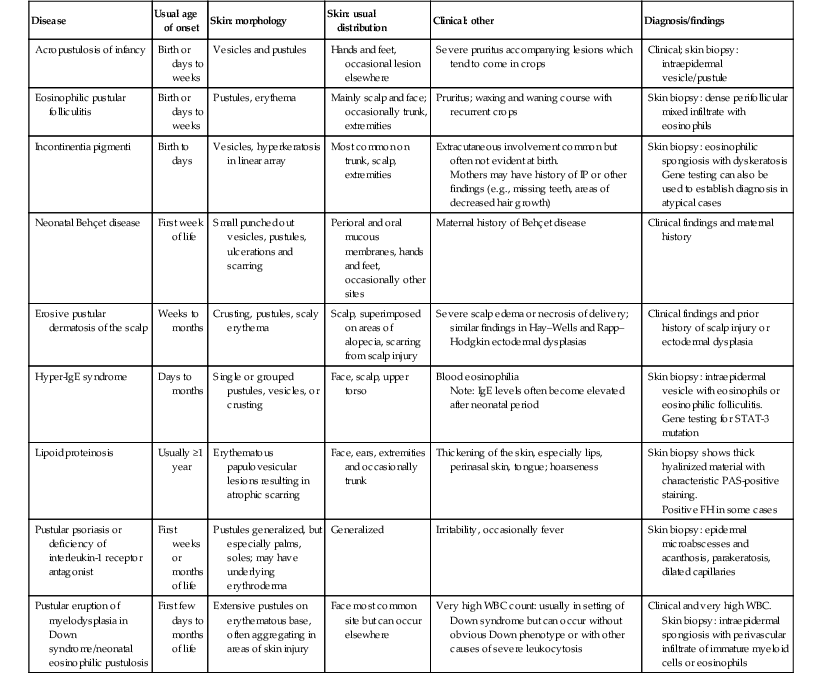

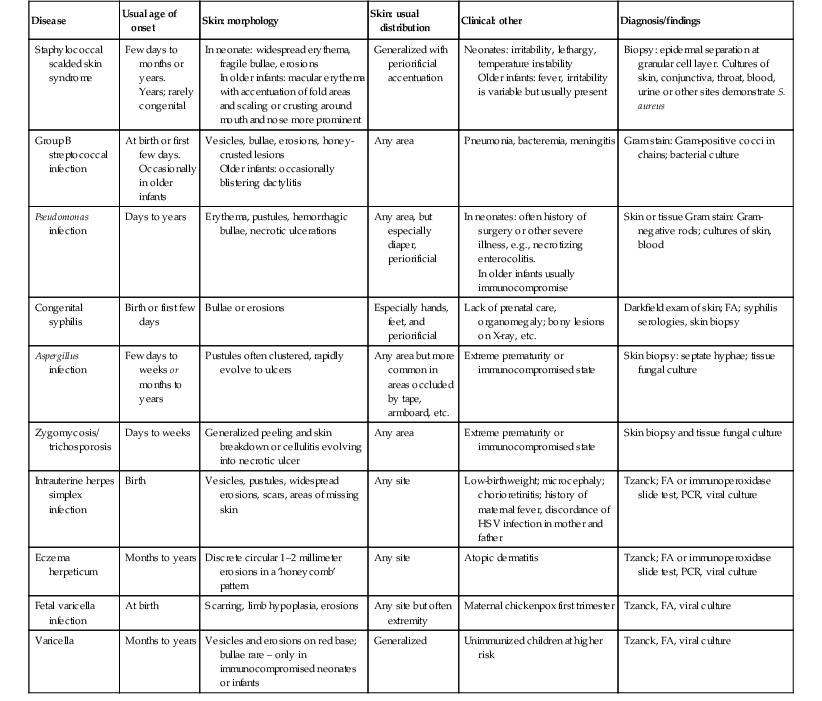

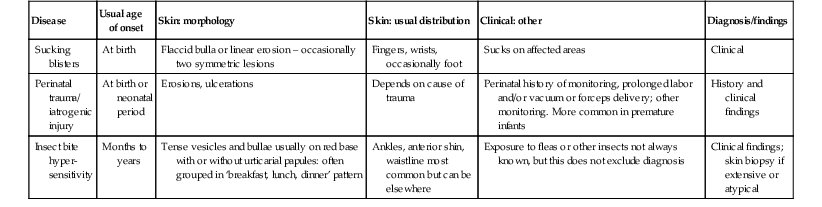

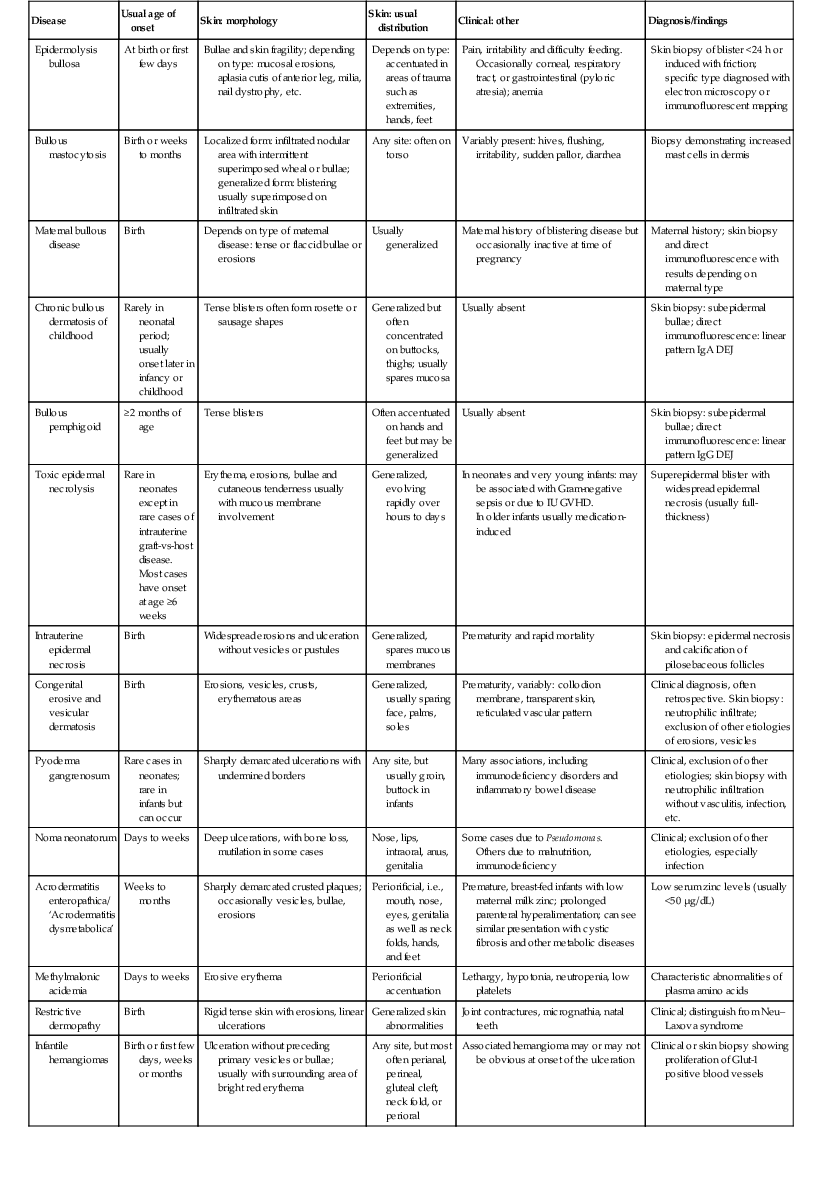

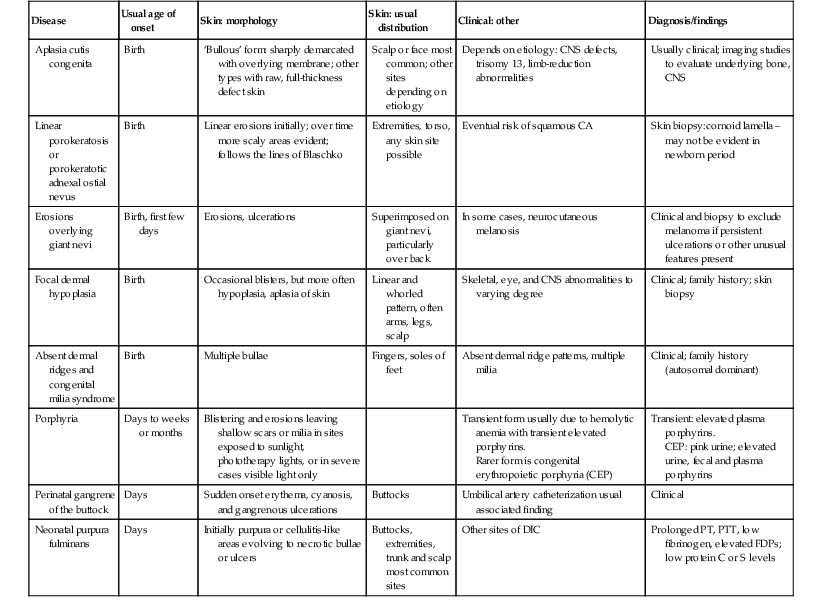

Because of the wide range of diagnoses discussed in this chapter, there are boxes and tables to help with a systematic approach to evaluation and differential diagnosis. Tables 10.1–10.3 summarize key findings and differential diagnosis of vesiculopustular diseases in newborns and infants, including infectious causes, relatively common transient skin lesions, and uncommon and rare causes of this clinical presentation. Tables 10.4–10.6 summarize these same categories for the differential diagnosis of bullae, erosions, and ulcerations. Box 10.1 lists conditions in neonates where pustules and vesicles predominate, Box 10.2 lists the conditions in neonates where bullae predominate, and Box 10.3 lists conditions in neonates where erosions or ulcerations may predominate.

TABLE 10.1

Differential diagnosis of vesiculopustular diseases in newborns and infants – Infectious causes

| Disease | Usual age of onset | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Diagnosis/findings |

| Staphylococcal pyoderma | Neonatal through infancy | Pustules, bullae, occasionally vesicles; crusted impetigo, folliculitis with follicular-based papules, pustules or furuncles | Any site: in neonates often concentrated in the diaper area and periumbilical skin. Infants: anywhere but often in fold areas, around mouth and nose. Perianal erythema similar to perianal Strep. |

If toxin-producing S. aureus may occur in epidemics. In this setting, often collarettes of scale at periphery | Gram stain: PMNs Gram-positive cocci in clusters. Bacterial culture |

| Group A streptococcal infection | Neonatal through infancy | Isolated pustules, honey-crusted areas, bullae, moist erythema. Perianal erythema with or without fissures, erosions or pustules. Blistering distal dactylitis |

Any site including palms, soles. In older infants characteristic presentations may include blistering distal dactylitis on volar fingertips; perianal ‘dermatitis’ |

Rare in neonates but may have other findings suggesting sepsis. Infants may have fever or other signs of systemic infection (more than with S. aureus), positive history of exposure to Strep. throat in family member |

Gram stain: Gram-positive cocci in chains; bacterial culture, rapid Strep. test. In older children throat culture may also be positive |

| Group B streptococcal infection (GBS) | In neonates – rare. In infants uncommon but similar to Group A Strep. infection |

Vesicles bullae, erosions, honey-crusted lesions | Any area including perianal and distal dactylitis | Neonates may have GBS systemic infection. In older children GBS is not always a pathogen – can represent colonization | Gram stain: Gram-positive cocci in chains; bacterial culture |

| Listeriosis | Birth, first few hours | Hemorrhagic pustules and petechiae | Generalized, especially trunk and extremities | Sepsis; respiratory distress; maternal fever, preterm labor | Gram-positive rods; bacterial culture skin and other sites |

| Haemophilus influenzae infection | Birth or first few days | Vesicles, crusted areas | No specific site predisposed | Bacteremia, meningitis may be present | Gram-negative bacilli; bacterial culture |

| Pseudomonas infection | Days to weeks. Later onset months to years |

Erythema, pustules, hemorrhagic bullae, necrotic ulcerations | Any area, but especially diaper, periorificial | History of illness in neonatal period, Immunocompromised host; occasionally immunocompetent infant | Skin or tissue Gram stain: Gram-negative rods; cultures skin, blood |

| Congenital and neonatal candidiasis | Birth or first few days of life | Erythema, small papules and pustules. Burn-like dermatitis with scaling may develop in extremely premature infants even after a few weeks of life |

Any part of body; upper torso, palms, soles often involved | Risk factors include prematurity. Foreign body in cervix/uterus |

KOH: hyphae, budding yeast; placental lesions. Skin culture can grow on standard bacterial media. Skin biopsy may be helpful if KOH negative |

| Candida albicans infection | Neonates and infants | Usual: Beefy red patches with overlying fine scale, satellite papules and pustules. Less common: moist erythema in folds |

Diaper or other intertriginous area | Usually otherwise healthy | KOH: hyphae, budding yeast if pustules are present |

| Aspergillus infection | Few days to weeks | Pustules often clustered, rapidly evolve to ulcers | Any area | Extreme prematurity usually present | Skin biopsy: septate hyphae; tissue fungal culture |

| Intrauterine herpes simplex | Birth; first few days of life | Vesicles, pustules, widespread erosions, congenital scars, areas of missing skin | Any site but scalp often affected with aplasia cutis-like areas | Signs of TORCH infections, e.g., low-birthweight; microcephaly, chorioretinitis | Tzanck; FA or immunoperoxidase slide test, PCR, viral culture |

| Neonatal herpes simplex | Usually 5–14 days | Vesicles, pustules, crusts, erosions | Any site; especially scalp, torso; may involve mucosa | Signs of sepsis; irritability, lethargy | Tzanck; FA or immunoperoxidase slide test, PCR, viral culture |

| Herpes simplex infection: older infants | Weeks to years | Primary gingivostomatitis. Recurrent HSV Eczema herpeticum: erosions, small vesicles and punched-out erosions Herpetic whitlow: grouped vesicles, pustules or bullae |

Intra- and perioral vesicles erosions and erythema Grouped vesicles erythematous base, any site Often face but any site – pattern may be grouped in some areas but trail off in others Acral skin, usually finger or toe |

Fever, irritability, adenopathy if primary. Often recurs in same site, sun exposure may provoke. In setting of atopic dermatitis, usual moderate to severe. May mimic bacterial dactylitis |

Tzanck; FA or immunoperoxidase slide test, PCR, viral culture |

| Neonatal varicella | 0–14 days | Vesicles on erythematous base; Lesions usually in same stage of development | Generalized distribution, often much more widespread than outside newborn period | Maternal primary varicella infection 7 days before to 2 days after delivery | Tzanck, FA, viral culture |

| Herpes zoster | Neonates and infants | Vesicles on erythematous base in dermatomal pattern | Typically extremity or torso | Maternal primary varicella infection during pregnancy OR primary varicella early in life | Tzanck, FA, viral culture |

| Primary varicella (Chickenpox) | Weeks to years | Crops of lesions at varying stages. Vesicles on erythematous base | Often starts on scalp, with accentuation of torso, but can be generalized | More common in unimmunized infants but can occur in less pronounced form in immunized infants (usually less vesicular) | Tzanck, FA, viral culture |

| Enteroviral exanthems | Weeks to years | Hand, foot, mouth: oval gray vesicles; Other enteroviral exanthems; Small vesicles, bullae, eczema herpeticum-like petechial |

Intraoral; Acral distribution with accentuation of palms, soles, diaper area Generalized |

Occasionally fever, vomiting, diarrhea, upper respiratory symptoms; Skin pain or itch; Several weeks later: onychomadesis |

PCR or viral culture: best yield are nasopharynx, rectum, vesicular skin lesions |

| Scabies | Usually 3–4 weeks or older | Multiple morphologies in the same patient i.e., papules, wheals, nodules, crusted areas, vesicles, burrows | Accentuated axillae, feet, wrists, may occur anywhere | Pruritus. Usually family members with itching, rash | Scabies prep demonstrating mites, eggs, or feces; clinical |

| Chikungunya virus | Infants, weeks to years | Vesicles or bullae | Generalized | Epidemics in developing countries; Fever |

TABLE 10.2

Differential diagnosis of vesiculopustular diseases – Transient skin lesions

| Disease | Usual age of onset | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Diagnosis/findings |

| Erythema toxicum neonatorm | Usually 24–28 h, but can be birth to 2 weeks | Erythematous macules, papules, pustules, wheals | Anywhere except palms, soles | Term infants >2500 g | Clinical; Wright’s stain: eosinophils |

| Neonatal pustular melanosis | Birth or shortly thereafter but collarettes of scale or hyperpigmented macules occasionally noted at a few days to weeks; not at birth | Pustules without underlying erythema; collarettes of scale; hyperpigmented macules; lesions may be clustered together | Anywhere; most often forehead, ears, back, fingers, toes | Term infants; more common in black infants | Clinical; Wright’s stain: PMNs, occasional eosinophil, cellular debris |

| Miliaria crystallina | Birth, neonatal period or later in infancy | Fragile vesicles without underlying erythema | Forehead, upper trunk, arms most common | Can be congenital but in acquired cases typically a history of fever | Clinical; Wright, Gram and Tzanck preps negative |

| Miliaria rubra | Neonatal or infancy | Erythematous papules with superimposed pustules typically concentrated in one or two areas; not generalized | Forehead, upper trunk, arms most common | Sometimes history of overwarming, fever, or use of occlusive dressing or garment | Clinical; Wright, Gram and Tzanck preps negative |

| Neonatal ‘acne’ (benign cephalic pustulosis) | Days to weeks | Papules and pustules on erythematous base | Cheeks, forehead, eyelids, neck, upper chest, scalp | Otherwise well; may have scaling in scalp | Usually clinical; Giemsa: negative or fungal spores, neutrophils |

TABLE 10.3

Differential diagnosis of vesiculopustular diseases – Uncommon and rare causes

| Disease | Usual age of onset | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Diagnosis/findings |

| Acropustulosis of infancy | Birth or days to weeks | Vesicles and pustules | Hands and feet, occasional lesion elsewhere | Severe pruritus accompanying lesions which tend to come in crops | Clinical; skin biopsy: intraepidermal vesicle/pustule |

| Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis | Birth or days to weeks | Pustules, erythema | Mainly scalp and face; occasionally trunk, extremities | Pruritus; waxing and waning course with recurrent crops | Skin biopsy: dense perifollicular mixed infiltrate with eosinophils |

| Incontinentia pigmenti | Birth to days | Vesicles, hyperkeratosis in linear array | Most common on trunk, scalp, extremities | Extracutaneous involvement common but often not evident at birth. Mothers may have history of IP or other findings (e.g., missing teeth, areas of decreased hair growth) |

Skin biopsy: eosinophilic spongiosis with dyskeratosis Gene testing can also be used to establish diagnosis in atypical cases |

| Neonatal Behçet disease | First week of life | Small punched out vesicles, pustules, ulcerations and scarring | Perioral and oral mucous membranes, hands and feet, occasionally other sites | Maternal history of Behçet disease | Clinical findings and maternal history |

| Erosive pustular dermatosis of the scalp | Weeks to months | Crusting, pustules, scaly erythema | Scalp, superimposed on areas of alopecia, scarring from scalp injury | Severe scalp edema or necrosis of delivery; similar findings in Hay–Wells and Rapp–Hodgkin ectodermal dysplasias | Clinical findings and prior history of scalp injury or ectodermal dysplasia |

| Hyper-IgE syndrome | Days to months | Single or grouped pustules, vesicles, or crusting | Face, scalp, upper torso | Blood eosinophilia Note: IgE levels often become elevated after neonatal period |

Skin biopsy: intraepidermal vesicle with eosinophils or eosinophilic folliculitis. Gene testing for STAT-3 mutation |

| Lipoid proteinosis | Usually ≥1 year | Erythematous papulovesicular lesions resulting in atrophic scarring | Face, ears, extremities and occasionally trunk | Thickening of the skin, especially lips, perinasal skin, tongue; hoarseness | Skin biopsy shows thick hyalinized material with characteristic PAS-positive staining. Positive FH in some cases |

| Pustular psoriasis or deficiency of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist | First weeks or months of life | Pustules generalized, but especially palms, soles; may have underlying erythroderma | Generalized | Irritability, occasionally fever | Skin biopsy: epidermal microabscesses and acanthosis, parakeratosis, dilated capillaries |

| Pustular eruption of myelodysplasia in Down syndrome/neonatal eosinophilic pustulosis | First few days to months of life | Extensive pustules on erythematous base, often aggregating in areas of skin injury | Face most common site but can occur elsewhere | Very high WBC count: usually in setting of Down syndrome but can occur without obvious Down phenotype or with other causes of severe leukocytosis | Clinical and very high WBC. Skin biopsy: intraepidermal spongiosis with perivascular infiltrate of immature myeloid cells or eosinophils |

TABLE 10.4

Differential diagnosis of bullae, erosions, and ulcerations – Infectious causes

| Disease | Usual age of onset | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Diagnosis/findings |

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome | Few days to months or years. Years; rarely congenital |

In neonate: widespread erythema, fragile bullae, erosions In older infants: macular erythema with accentuation of fold areas and scaling or crusting around mouth and nose more prominent |

Generalized with periorificial accentuation | Neonates: irritability, lethargy, temperature instability Older infants: fever, irritability is variable but usually present |

Biopsy: epidermal separation at granular cell layer. Cultures of skin, conjunctiva, throat, blood, urine or other sites demonstrate S. aureus |

| Group B streptococcal infection | At birth or first few days. Occasionally in older infants |

Vesicles, bullae, erosions, honey-crusted lesions Older infants: occasionally blistering dactylitis |

Any area | Pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis | Gram stain: Gram-positive cocci in chains; bacterial culture |

| Pseudomonas infection | Days to years | Erythema, pustules, hemorrhagic bullae, necrotic ulcerations | Any area, but especially diaper, periorificial | In neonates: often history of surgery or other severe illness, e.g., necrotizing enterocolitis. In older infants usually immunocompromise |

Skin or tissue Gram stain: Gram-negative rods; cultures of skin, blood |

| Congenital syphilis | Birth or first few days | Bullae or erosions | Especially hands, feet, and periorificial | Lack of prenatal care, organomegaly; bony lesions on X-ray, etc. | Darkfield exam of skin; FA; syphilis serologies, skin biopsy |

| Aspergillus infection | Few days to weeks or months to years | Pustules often clustered, rapidly evolve to ulcers | Any area but more common in areas occluded by tape, armboard, etc. | Extreme prematurity or immunocompromised state | Skin biopsy: septate hyphae; tissue fungal culture |

| Zygomycosis/ trichosporosis | Days to weeks | Generalized peeling and skin breakdown or cellulitis evolving into necrotic ulcer | Any area | Extreme prematurity or immunocompromised state | Skin biopsy and tissue fungal culture |

| Intrauterine herpes simplex infection | Birth | Vesicles, pustules, widespread erosions, scars, areas of missing skin | Any site | Low-birthweight; microcephaly; chorioretinitis; history of maternal fever, discordance of HSV infection in mother and father | Tzanck; FA or immunoperoxidase slide test, PCR, viral culture |

| Eczema herpeticum | Months to years | Discrete circular 1–2 millimeter erosions in a ‘honeycomb’ pattern | Any site | Atopic dermatitis | Tzanck; FA or immunoperoxidase slide test, PCR, viral culture |

| Fetal varicella infection | At birth | Scarring, limb hypoplasia, erosions | Any site but often extremity | Maternal chickenpox first trimester | Tzanck, FA, viral culture |

| Varicella | Months to years | Vesicles and erosions on red base; bullae rare – only in immunocompromised neonates or infants | Generalized | Unimmunized children at higher risk | Tzanck, FA, viral culture |

TABLE 10.5

Differential diagnosis of bullae, erosions, and ulcerations – Transient skin lesions

| Disease | Usual age of onset | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Diagnosis/findings |

| Sucking blisters | At birth | Flaccid bulla or linear erosion – occasionally two symmetric lesions | Fingers, wrists, occasionally foot | Sucks on affected areas | Clinical |

| Perinatal trauma/ iatrogenic injury | At birth or neonatal period | Erosions, ulcerations | Depends on cause of trauma | Perinatal history of monitoring, prolonged labor and/or vacuum or forceps delivery; other monitoring. More common in premature infants | History and clinical findings |

| Insect bite hyper-sensitivity | Months to years | Tense vesicles and bullae usually on red base with or without urticarial papules: often grouped in ‘breakfast, lunch, dinner’ pattern | Ankles, anterior shin, waistline most common but can be elsewhere | Exposure to fleas or other insects not always known, but this does not exclude diagnosis | Clinical findings; skin biopsy if extensive or atypical |

TABLE 10.6

Differential diagnosis of bullae, erosions, and ulcerations – Uncommon and rare causes

| Disease | Usual age of onset | Skin: morphology | Skin: usual distribution | Clinical: other | Diagnosis/findings |

| Epidermolysis bullosa | At birth or first few days | Bullae and skin fragility; depending on type: mucosal erosions, aplasia cutis of anterior leg, milia, nail dystrophy, etc. | Depends on type: accentuated in areas of trauma such as extremities, hands, feet | Pain, irritability and difficulty feeding. Occasionally corneal, respiratory tract, or gastrointestinal (pyloric atresia); anemia | Skin biopsy of blister <24 h or induced with friction; specific type diagnosed with electron microscopy or immunofluorescent mapping |

| Bullous mastocytosis | Birth or weeks to months | Localized form: infiltrated nodular area with intermittent superimposed wheal or bullae; generalized form: blistering usually superimposed on infiltrated skin | Any site: often on torso | Variably present: hives, flushing, irritability, sudden pallor, diarrhea | Biopsy demonstrating increased mast cells in dermis |

| Maternal bullous disease | Birth | Depends on type of maternal disease: tense or flaccid bullae or erosions | Usually generalized | Maternal history of blistering disease but occasionally inactive at time of pregnancy | Maternal history; skin biopsy and direct immunofluorescence with results depending on maternal type |

| Chronic bullous dermatosis of childhood | Rarely in neonatal period; usually onset later in infancy or childhood | Tense blisters often form rosette or sausage shapes | Generalized but often concentrated on buttocks, thighs; usually spares mucosa | Usually absent | Skin biopsy: subepidermal bullae; direct immunofluorescence: linear pattern IgA DEJ |

| Bullous pemphigoid | ≥2 months of age | Tense blisters | Often accentuated on hands and feet but may be generalized | Usually absent | Skin biopsy: subepidermal bullae; direct immunofluorescence: linear pattern IgG DEJ |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | Rare in neonates except in rare cases of intrauterine graft-vs-host disease. Most cases have onset at age ≥6 weeks |

Erythema, erosions, bullae and cutaneous tenderness usually with mucous membrane involvement | Generalized, evolving rapidly over hours to days | In neonates and very young infants: may be associated with Gram-negative sepsis or due to IU GVHD. In older infants usually medication-induced |

Superepidermal blister with widespread epidermal necrosis (usually full-thickness) |

| Intrauterine epidermal necrosis | Birth | Widespread erosions and ulceration without vesicles or pustules | Generalized, spares mucous membranes | Prematurity and rapid mortality | Skin biopsy: epidermal necrosis and calcification of pilosebaceous follicles |

| Congenital erosive and vesicular dermatosis | Birth | Erosions, vesicles, crusts, erythematous areas | Generalized, usually sparing face, palms, soles | Prematurity, variably: collodion membrane, transparent skin, reticulated vascular pattern | Clinical diagnosis, often retrospective. Skin biopsy: neutrophilic infiltrate; exclusion of other etiologies of erosions, vesicles |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Rare cases in neonates; rare in infants but can occur | Sharply demarcated ulcerations with undermined borders | Any site, but usually groin, buttock in infants | Many associations, including immunodeficiency disorders and inflammatory bowel disease | Clinical, exclusion of other etiologies; skin biopsy with neutrophilic infiltration without vasculitis, infection, etc. |

| Noma neonatorum | Days to weeks | Deep ulcerations, with bone loss, mutilation in some cases | Nose, lips, intraoral, anus, genitalia | Some cases due to Pseudomonas. Others due to malnutrition, immunodeficiency |

Clinical; exclusion of other etiologies, especially infection |

| Acrodermatitis enteropathica/ ‘Acrodermatitis dysmetabolica’ |

Weeks to months | Sharply demarcated crusted plaques; occasionally vesicles, bullae, erosions | Periorificial, i.e., mouth, nose, eyes, genitalia as well as neck folds, hands, and feet | Premature, breast-fed infants with low maternal milk zinc; prolonged parenteral hyperalimentation; can see similar presentation with cystic fibrosis and other metabolic diseases | Low serum zinc levels (usually <50 µg/dL) |

| Methylmalonic acidemia | Days to weeks | Erosive erythema | Periorificial accentuation | Lethargy, hypotonia, neutropenia, low platelets | Characteristic abnormalities of plasma amino acids |

| Restrictive dermopathy | Birth | Rigid tense skin with erosions, linear ulcerations | Generalized skin abnormalities | Joint contractures, micrognathia, natal teeth | Clinical; distinguish from Neu–Laxova syndrome |

| Infantile hemangiomas | Birth or first few days, weeks or months | Ulceration without preceding primary vesicles or bullae; usually with surrounding area of bright red erythema | Any site, but most often perianal, perineal, gluteal cleft, neck fold, or perioral | Associated hemangioma may or may not be obvious at onset of the ulceration | Clinical or skin biopsy showing proliferation of Glut-1 positive blood vessels |

| Aplasia cutis congenita | Birth | ‘Bullous’ form: sharply demarcated with overlying membrane; other types with raw, full-thickness defect skin | Scalp or face most common; other sites depending on etiology | Depends on etiology: CNS defects, trisomy 13, limb-reduction abnormalities | Usually clinical; imaging studies to evaluate underlying bone, CNS |

| Linear porokeratosis or porokeratotic adnexal ostial nevus | Birth | Linear erosions initially; over time more scaly areas evident; follows the lines of Blaschko | Extremities, torso, any skin site possible | Eventual risk of squamous CA | Skin biopsy:cornoid lamella – may not be evident in newborn period |

| Erosions overlying giant nevi | Birth, first few days | Erosions, ulcerations | Superimposed on giant nevi, particularly over back | In some cases, neurocutaneous melanosis | Clinical and biopsy to exclude melanoma if persistent ulcerations or other unusual features present |

| Focal dermal hypoplasia | Birth | Occasional blisters, but more often hypoplasia, aplasia of skin | Linear and whorled pattern, often arms, legs, scalp | Skeletal, eye, and CNS abnormalities to varying degree | Clinical; family history; skin biopsy |

| Absent dermal ridges and congenital milia syndrome | Birth | Multiple bullae | Fingers, soles of feet | Absent dermal ridge patterns, multiple milia | Clinical; family history (autosomal dominant) |

| Porphyria | Days to weeks or months | Blistering and erosions leaving shallow scars or milia in sites exposed to sunlight, phototherapy lights, or in severe cases visible light only | Transient form usually due to hemolytic anemia with transient elevated porphyrins. Rarer form is congenital erythropoietic porphyria (CEP) |

Transient: elevated plasma porphyrins. CEP: pink urine; elevated urine, fecal and plasma porphyrins |

|

| Perinatal gangrene of the buttock | Days | Sudden onset erythema, cyanosis, and gangrenous ulcerations | Buttocks | Umbilical artery catheterization usual associated finding | Clinical |

| Neonatal purpura fulminans | Days | Initially purpura or cellulitis-like areas evolving to necrotic bullae or ulcers | Buttocks, extremities, trunk and scalp most common sites | Other sites of DIC | Prolonged PT, PTT, low fibrinogen, elevated FDPs; low protein C or S levels |

Bacterial infections (see Chapter 12)

Staphylococcus aureus infections

Skin infections caused by S. aureus are relatively common in newborns and infants. Epidemic outbreaks are occasionally seen in newborn and intensive care nurseries.8–10 In recent years, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections have been increasingly reported in hospital nursery and maternity units, paralleling a trend toward such infections in other settings. Interestingly, most have had the molecular fingerprint of community-acquired (CA-MRSA), rather than nosocomial MRSA.5,8,9 Two forms of S. aureus infection involving the skin can occur: direct skin infection and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, caused by staphylococcal toxins.

Staphylococcus aureus pyoderma

Superficial skin infections with S. aureus (staphylococcal pyoderma) can result in crusted impetigo, bullous impetigo, and pustular folliculitis (Figs 10.1, 10.2). Deeper skin infections can result in furunculosis, cellulitis, and abscesses. Infection is virtually never present at birth, but develops in the first days to weeks of life. It typically presents with discrete vesicles and pustules. Toxin-producing S. aureus can present with tense, fragile vesicles and bullae. As these rupture, they may often leave either moist superficial erosions or crusted areas with a collarette of scale (Fig. 10.3). Superficial staphylococcal infection can also present with crusted impetigo without clinically obvious vesicles, pustules, or bullae.11

Common sites of involvement include the neck folds, diaper area, and axillae. More extensive cases of generalized bullous impetigo are occasionally seen.12 The patients are usually otherwise well, without signs of more generalized infection. In two reports of CA-MRSA outbreaks in a well-baby nursery, neonates presented in the first 2.5 weeks of life with discrete pustules often in the diaper area but also on the trunk or posterior auricular surface; two babies had cellulitis. The skin lesions cleared rapidly with topical and/or oral antimicrobials.8,9

In older infants, superficial infection can progress to invasive disease, especially in the malnourished or otherwise compromised host. In one study in India, 26% of pediatric patients with invasive staphylococcal disease had a preceding history of pustules.13 Staphylococcal infection can also cause a persistent perianal rash that involves the buttocks, in contrast to more localized perianal streptococcal disease.14 Blistering distal dactylitis (bullae on the volar tip of the digits usually due to Group A streptococcal infection) can rarely be caused by Staph in infants.15 Methicillin-sensitive and -resistant Staphylococcus, as well as herpes simplex infections can cause similar bullae; co-infection with Staph and HSV has been documented in a child.16,17 Infants with atopic dermatitis and staphylococcal superinfection usually present with crusting rather than intact pustules because of the tendency to scratch the primary lesion. Diagnosis and management are discussed in Chapter 12.

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is an acute, potentially life-threatening disease caused by exotoxin-producing S. aureus, usually phage types 1, 2, or 3. Although epidemics as well as sporadic outbreaks of SSSS have been reported, including in newborn nurseries,18 it is still an uncommon to rare condition. A population-based study in Germany found an incidence of approximately 0.1 cases per million inhabitants per year (including all ages) with a bimodal distribution of ages: young children and older adults.19 In a group of neonates and infants with erythroderma, SSSS was the etiology of their skin findings in only 7%.20 Only a few cases of congenital SSSS have been reported; the vast majority of infants present between 3 and 7 days of age or older, with an abrupt onset of cutaneous erythema, tenderness, and widespread areas of skin fragility, superficial blistering, and/or erosions.21–24 Erythema often begins on the face, especially around the mouth. In newborns, flaccid blisters usually appear within 24–48 h and quickly erode, producing areas of superficially denuded skin. These erosions are particularly prominent in areas of mechanical stress, such as the shoulders, buttocks, body folds, feet, and hands. When firmly rubbed, the skin is easily separated from the underlying epidermis (Nikolsky’s sign). A milder, but more common form of SSSS, characterized by erythema, tiny erosions or pustules, with or without a scarlatiniform rash is often seen in older infants and children. Periorificial accentuation with scale or crusting is a common feature of both forms (Fig. 10.4).

Systemic signs such as temperature instability, irritability, and/or lethargy are common in neonates whereas infants are nearly always febrile. Perioral or periocular edema and mucopurulent conjunctivitis are sometimes present. Although the primary site of S. aureus infection is usually not the skin, occasionally a primary skin infection, such as an abscess, purulent umbilicus, or localized area of impetigo, may be the source of disease.11

Diagnosis is made by skin biopsy, which demonstrates a cleavage plane in the upper epidermis with acantholytic cells and minimal dermal inflammation. To speed diagnosis, a snip biopsy of exfoliating portions of the skin can be sent for frozen section. The differential diagnosis includes toxic epidermal necrolysis, epidermolysis bullosa, boric acid poisoning, and certain metabolic disorders such as methylmalonic acidemia.25,26 The management of SSSS is discussed in Chapter 12.

Streptococcal infection

Several epidemics of group A streptococcus (GAS) have been reported in the newborn period. Although most infants present with omphalitis or a moist umbilical cord stump, in rare cases isolated pustules may be the presenting sign of GAS infection. GAS can also cause a form of intertrigo in infancy.27–29 Generalized sepsis, cellulitis, meningitis, and pneumonia are occasionally seen.30,31 Because neonatal group A streptococcal infection can result in an invasive infection, parenteral antibiotics should be considered, and infants observed closely for signs of systemic illness. Although bacterial cultures are the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosis, rapid antigen testing for GAS can be used while awaiting culture.

In older infants, clinical presentations of localized cutaneous GAS infection include impetigo, streptococcal intertrigo, perianal streptococcal dermatitis, blistering dactylitis and atopic dermatitis with secondary streptococcal infection. GAS impetigo can be difficult to distinguish from that caused by S. aureus: both have crusting and erosions and occasional pustules. In addition, infants with GAS skin infections may be more irritable and may be febrile, a finding less common in S. aureus impetigo. Infants with streptococcal intertrigo, have moist eroded areas in the folds of the neck, axilla, groin, or perianal area that can be mistaken for candidal infection.27–29 In young children with blistering distal dactylitis, a large vesicle or bulla develops on the volar aspect of tips of fingers or toes.32 In infants with atopic dermatitis, GAS causes crusting and pustules that may be deep-seated and may involve the palms and soles – a feature less likely to be due to S. aureus alone; coinfection with staphylococcus can occur (Fig. 10.5![]() ).33,34

).33,34