8 Vertigo

Introduction

Vertigo is a very specific word derived from two words, namely ‘vertere’, to turn and ‘igo’, a condition.1 It implies an unreal sensation of motion, meaning that the patient perceives the sensation of movement when, in fact, the patient is stationary. Thus history taking when exploring what might prove to be true vertigo must explore the question of unreal motion, which can be objective, implying the external environment is perceived as moving, or subjective, in which the patient feels as if they are moving while the surroundings are stationary. Both equate to vertigo.

Perhaps the most common cause for vertigo to be referred to a neurologist is that of benign positional paroxysmal vertigo (BPPV), which can and should be successfully treated by the family doctor, although more often than not it does result in referral to either a neurologist or ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon.

Taking the History

Having confirmed that the basis for presentation is vertigo, the doctor needs to clarify its cause. The type and nature of the vertigo will help with diagnosis. Vertigo that occurs in bed, particularly after turning over in bed either right to left (or the converse), is more likely than not, going to be BPPV (see Table 8.1). Vertigo that follows an upper respiratory tract infection will probably be caused by labyrinthitis or vestibular neuronitis (see Table 8.1). Vestibular neuronitis (labyrinthitis) is usually of acute or subacute onset, causing rotatory vertigo together with nausea and postural loss of balance.

| Cause | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Labyrinthitis (also called vestibular or peripheral neuronitis) | Follows an upper respiratory tract infection with acute or subacute onset |

| Benign positional paroxysmal vertigo | Occurs when turning in bed or with positional changes |

| Ménière’s disease | May precede or follow hearing loss associated with increased vomiting, tinnitus, debilitating vertigo |

| Barotrauma | History of diving |

| Otosclerosis | Difficulty hearing with background noise |

| Herpes zoster oticus | Often associated with Bell’s palsy (Ramsay Hunt syndrome) Often very painful |

| Perilymphatic fistula | Painful |

| Cholestatoma erosion | Rare and often only diagnosed with imaging |

Vertigo associated with profound vomiting and deafness may be a case of Ménière’s disease (see Table 8.1). Ménière’s disease often has a greater problem with tinnitus, which may precede the complaint of loss of hearing. Other peripheral causes of vertigo are fairly rare (see Table 8.1).2

When considering vertigo, one should not overlook motion-induced vertigo that may relate to either peripheral vestibulitis or BPPV. Psychogenic causes of vertigo, as are reported in the patient who claims seasickness even when watching the ocean from dry land, may need desensitising and referral is warranted. Psychogenic vertigo may also occur in conjunction with panic disorders or hyperventilation.

There are also central causes of vertigo (Table 8.2),3 acknowledging that vertigo may be provoked by dysfunction anywhere along the vestibulo-cochlear pathway. This travels from the receptors in the ears, which record motion and position within the environment, and travel along the 8th cranial nerve to the pontine, brainstem connections. Hearing is also dependent upon competence of the 8th cranial nerve and, with mutual passage, both can be ‘interrupted’ by common aetiologies.

TABLE 8.2 Central causes of vertigo

| Cause | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Ingestion of substances such as alcohol or medications | History of ingestion More widespread incoordination ataxia |

| Transient ischaemic attacks and strokes | Sudden onset in patients with history of vasculopathy (possibly diabetes and hypertension) and often smokers |

| Trauma affecting the brainstem (pons) with possible haemorrhage | History of trauma, assault or accident prior to onset |

| Acoustic neuroma | Slow onset and associated with hearing loss |

| Multiple sclerosis | Symptoms divorced in time and place |

| Migraines | Headache may be a significant feature but need not be so |

| Psychogenic causes | Psychogenic true vertigo is exceedingly rare but possible |

Perhaps the most common central cause of vertigo, often associated with ataxia, incoordination and other definitive symptoms, is the ingestion of toxic amounts of substances such as alcohol or medications; for example, anti-epileptic medications. These causes will often have other associated histories that make their diagnosis quite straightforward (see Table 8.2).

Damage to the pontine or cerebellar connections, as may occur with trauma, ischaemia (be it transient ischaemic attack or stroke), tumours of the cerebello-pontine angle (such as acoustic neuromas or pontine tumours like gliomas) or vascular anomalies, can all provoke true vertigo.4 Lesions in the brainstem may also have other cranial nerve abnormalities.

Tumours located in the cerebellopontine angle, such as acoustic neuromas or schwannomas, may evoke vertigo. The onset of symptoms may be slower than is the case with other causes. Less common causes of central vertigo may include migraines or multiple sclerosis, but the history should be self-explanatory. Vascular malformations may cause centrally-induced vertigo.

From the above it is established that vertigo can result from lesions anywhere along the vestibulo-cochlear pathway. Knowing the symptoms that attach to each location may enhance diagnostic acumen (see Table 8.3).

TABLE 8.3 Vertigo-associated symptoms that may assist with localisation

| Location | Symptom |

|---|---|

| Inner ear |

Examination

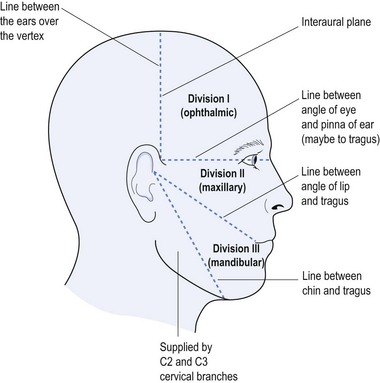

The history will direct attention in the appropriate direction. Cranial nerve examination is the usual formal starting point. The ophthalmoscope is particularly useful. It may allow the definition of nystagmus even in the primary position, as patients often have difficulty focusing on a distant object with the bright light of the ophthalmoscope. Evidence of raised intracranial pressure may suggest a brainstem or cerebellar pontine angle space-occupying lesion if vertigo is the initial complaint. Ophthalmoplegia may suggest multiple sclerosis; while 6th or 7th cranial nerve deficit may imply pontine lesion; and deafness suggests vestibulo–cochlear damage, either centrally or peripherally.

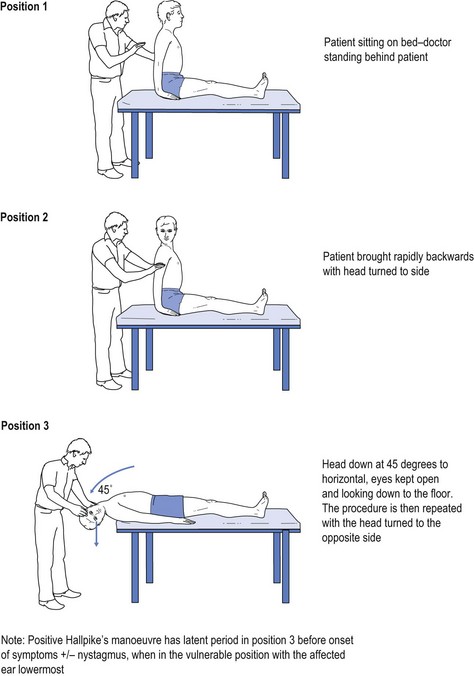

One of the best-known tests, used specifically for BPPV, is Hallpike’s manoeuvre. In this the patient sits upright on the examination couch, is drawn back quickly and advised to keep the eyes open. The head is turned such that the ear is lowermost and the head is held at an angle of 45° to the horizontal. The patient is asked to keep the eyes open and to look down to the floor. This evokes a torsional affect on the calcium carbonate laden hairs in the inner ear, causing a sensation of rotation towards the lowermost ear, which occurs after a brief latent period. This is repeated so that both sides are tested (see Fig 8.1).5 Absence of the latent period is more indicative of a central cause for the vertigo.

Other useful tests include the ‘head impulse test’ and the Fukuda-Unterberger test.6 The ‘head impulse test’ assesses acute vestibulopathy with head turn to the affected ear evoking a delayed response with the need for a corrective saccade, eye movement, to maintain focus on an object. The Fukuda-Unterberger test causes the patient to deviate to the affected side when ‘marking time’, namely stepping or marching on the spot.

Investigations

The majority of patients with vertigo do not need sophisticated testing and the symptoms will be self-limiting. If this is not the case then specialist referral is appropriate.

Treatment

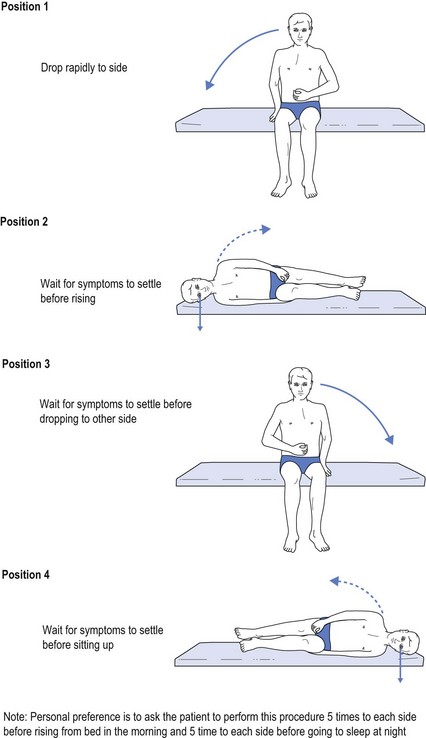

Treatment of BPPV does not usually require pharmacologic intervention unless the vertigo is so intrusive as to preclude quality of life. The most effective intervention is to use fatiguing exercises (see Fig 8.2) and the BPPV is also usually self-limiting, although it may recur. The best-known manoeuvre is the Epley manoeuvre, but it is not the one personally favoured. The one favoured is self-administered by the patient and is a variant of the Semont manoeuvre. The patient sits on the edge of the bed and drops to one side, waits for the vertigo and associated symptoms to improve, and then sits up again before performing the identical drop to the opposite side (see Fig 8.2). The patient does this, dropping to each side five to ten times in the morning upon waking and before getting up from bed, and at night before going to sleep.

Serc® (betahistamine) acts as a vasodilator thought to increase vascular supply to the inner ear, although it may also have other benefits for Ménière’s disease, at a dosage of 8–16 mg b.i.d.

1 Kuo CH, Pang L, Chang R. Vertigo: Part 1—Assessment in general practice. Australian Family Physician. 2008;37:341-347.

2 Baloh RW. Differentiating between peripheral and central causes of vertigo. J Neuro Sciences. 2004;221(1–2):117-119.

3 Furman JM, Whitney SL. Central causes of dizziness. Physical Therapy. 2000;80:179-187.

4 Labuguen RH. Initial evaluation of vertigo. American Family Physician. 2006;59(11–12):585-590.

5 Sato S, Ohashi T, Koizuka I. Physical therapy for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo patients with movement disability. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30:53-56.

6 Kuo CH, Pang L, Chang R. Vertigo: Part 2—Management in general practice. Australian Family Physician. 2008;37:409-413.