CHAPTER 32 Vertebroplasty

SCREENING OF PATIENTS REFERRED FOR VERTEBROPLASTY

Before considering vertebroplasty, one must perform a through history, physical examination, and review appropriate investigations including radiographic analysis. This information should be able to differentiate between the source of pain being vertebral compression fracture or other back problems such as disc herniation, facet arthropathy, or spinal stenosis.1

History should include the site of pain, cause, inciting event, date of origin, exacerbating factors, alleviating factors, analgesic use, and activities of daily living. The patient should be screened for allergies, medications, medical problems, and conditions which may prevent the patient from lying prone during the procedure. The origin of pain may coincide with minor trauma and is typically exacerbated during activity, movement, or while weight bearing, and is relieved by lying down. Physical examination will reveal a tender site corresponding with the fracture level. If multiple vertebral compression fractures are present, the origin of pain will be elicited by careful clinical examination and analysis of radiographic studies.1,2 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful in patients with multiple fractures and usually reveals edema within the marrow space of the vertebral body that is best visualized on sagittal T2-weighted images. Bone scans can also differentiate the symptomatic level from incidentally discovered fractures.3 Bone scan imaging may be indicated when considering vertebroplasty therapy for patients suffering from multiple vertebral compression fractures of uncertain age or in patients with nonlocalizing pain patterns. We do not, however, routinely perform bone scans.4

Blood investigations should include complete blood and platelet counts, measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, International Normalized Ratio, activated clotting time, and complete metabolic panel.5,6

CONSULTATION

The time of reporting for the procedure, postprocedure care, and time of discharge from the hospital should be explained. Informed consent must include a through explanation of the procedure, methods, the physician’s prior history of complications, and the expected outcome based on the physician’s own outcome data. The patient should also be informed that the addition of material (barium, tungsten or tantalum) to make the bone cement material opaque technically makes the cement a non-FDA-approved material.1,7

Timing

Early studies performed vertebroplasty only after conventional treatment (medication and rest) had failed.8 Later series have advocated treatment as early as weeks or days if the patient requires narcotic medication or admission to hospital secondary to pain. Others have recommended vertebroplasty within 4 months.3 Although late treatment is unlikely to be successful, there are case reports of patients being successfully treated after a few years.9

Even though some believe it is a reasonable indication,1 there are insufficient data to categorically support the treatment of painful tumor infiltration without fracture. In addition, it is unclear whether to treat before or after radiation therapy. Injection of cement into the vertebral body will likely dislodge marrow elements that could potentially be absorbed into the blood stream. This concern for causing metastatic dissemination suggests that vertebroplasty should be performed only after radiation therapy.

Prophylactic vertebroplasty is neither widely accepted nor approved for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures and no studies have been done to substantiate the utility of this practice.1

TECHNIQUE

We do not give any prophylactic antibiotics and prescribe antibiotics postoperatively for a week.

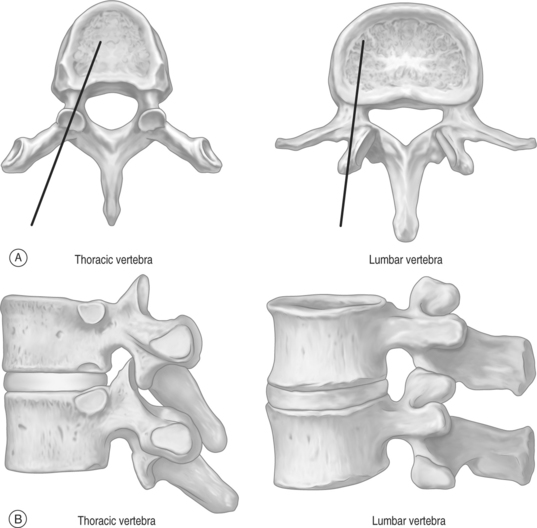

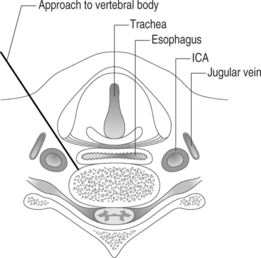

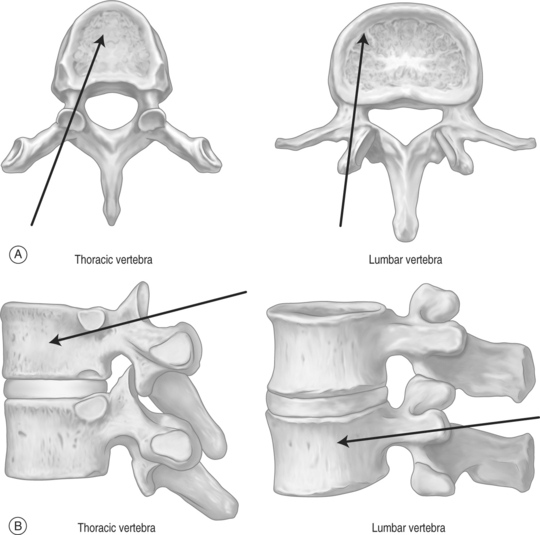

The thoracic and lumbar vertebral bodies are usually approached through one or, most commonly, both pedicles.2,8,21–27 Various approaches are used including a costovertebral,5 paravertebral, posterolateral, or anterolateral (cervical) approach. The parapedicular or transcostovertebral28 approach is used when a transpedicular approach cannot be used because of small pedicles, a fractured pedicle, or tumor invading the pedicle. Like most physicians, the authors prefer the transpedicular approach instead of the parapedicular approach, which may increase the chance of both a pneumothorax and that a paraspinous hematoma may not be controlled with application local pressure.6 The posterolateral approach increased the risk of injuring the exiting nerve root and segmental artery,6 and has largely been abandoned although some authors recommend it for lumbar vertebrae.20,23,28

There are many companies which supply cement and delivery equipment: Parallax Medical Inc./Arthrocare Corporation; Cook Group Inc.; Interpore Cross International Inc.; Interpore Cross International Inc./American OsteoMedix Corp.; Medtronic Inc./Medtronic Sofamor Danek; Orthofix International NV/Orthofix Inc.; Stryker Corp.; Tecres SPA.29 These sets contain stylets, needles, tubing, injectors, and injector barrels, but the end result is the same. The equipment allows one to inject cement into the anterior part of the vertebral body. Some authors have, however, modified the equipment and technique,30–33 and before these sets were available, operators recommended using 1 mL syringes for injection of cement.7,11,17,24

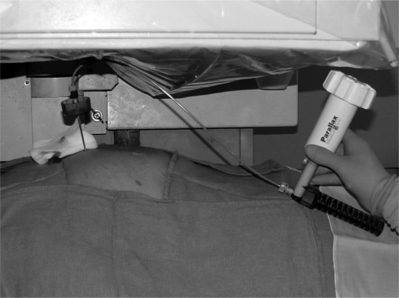

A small incision is made using a No. 11 knife blade and the introducer needle from the set is inserted (Fig. 32.4). A 15-gauge needle is used for cervical vertebrae and 10-gauge for thoracic and lumbar vertebrae.3 Currently, even thinner needles (13-gauge) are being used.6 The needle entry site is localized in the AP view. The authors use a diamond-tipped needle to start the entry.

The needle is held with forceps to minimize radiation exposure to the operator.6 After confirming the position, the vertebroplasty needle is advanced through the superior-lateral cortex of the pedicle (Fig. 32.5). The vertical and horizontal diameter of the pedicle increases from upper thoracic to lower lumbar vertebrae (Table. 32.1). Proximally, in the sagittal plane, the direction of the pedicle is more oblique. (Fig. 32.6)

| Pedicles | T3 | L4 |

|---|---|---|

| Vertical diameter | 0.7 cm | 1.5 cm |

| Horizontal diameter | 0.7 cm | 1.6 cm |

The authors start with a diamond-tipped needle and then change it to beveled needle to make directional adjustments.7 The bevel of the needle is directed so that the tip is pointed laterally to avoid the spinal canal.

In osteoporotic bones it may be easy to advance the needle by hand, but in cases where the bone is dense, as in pathologic fractures, a mallet is necessary to advance the needle.6 While advancing the needle by hand the direction of needle may change, and using the mallet may keep the needle advancing in the direction wanted. We invariably use a mallet to advance the needle as this provides much greater control of the needle direction. As the needle is slowly advanced through the pedicle, we are hypervigilant about the location of the needle tip and the orientation of the needle. At no point do we want to breach the medial wall and subject the patient to the risk of cement extravasation into the spinal canal. When we reach the anterior part of the pedicle on lateral view, the trocar should be just lateral to the medial border of the pedicle on anteroposterior view. This ensures we are not going to break the medial wall of the pedicle. In addition, we do not want to fracture the roof or the base of the pedicle and inadvertently pierce an exiting nerve root. Advancing the needle through the lateral border of the pedicle will deposit cement intramuscularly. We have experienced this latter scenario on a few occasions and it is not associated with any adverse effects. Theoretically, it is conceivable that the needle could be placed too close to the aorta if the needle breaks through the lateral margin of the left pedicle, but this is a highly unlikely event. It is also important to be sure that the angle of inclination will allow the needle to ultimately rest in the anterior one-third of the vertebral body. To obtain ideal terminal position, it is critical that one repeatedly re-checks the cephalocaudal tilt while traversing through the pedicle. It is very difficult to re-orient the angle of inclination once the needle has passed through the pedicle and enters the vertebral body. If the angle of inclination is too steep then gentle downward pressure on the hub will minimize this angle, especially if the needle is still within the pedicle. We emphasize the term ‘gentle’ since osteoporotic bone can easily fracture if aggressive motions are used. If such gentle pressure does not achieve the intended result, a beveled needle can be substituted for the diamond-tipped needle. The bevel can be rotated so that the needle courses in the direction of choice. After the needle is observed to enter the vertebral body using a lateral view, the AP perspective does not need to be checked until the cement is injected. An AP view is needed at three points during the procedure: when planning where to insert he needle, checking the progress of the needle as it courses through the pedicle, and then later when cement is injected. Once the needle is in the vertebral body it should be rotated so that the tip is opening medially.

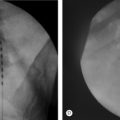

The typical concentration is 0.40 mL of PMMA powder (SimplexP; Stryker-Howmedica-Osteonics) combined with 6 g of sterile barium sulfate powder, tantalum,3,11 or tungsten (Figs 32.7, 32.8).10 The barium sulfate powder is included to better visualize the PMMA under fluoroscopy. The safety of the procedure depends on cement leakage rather than the type of cement used.41 In addition, before adding the 10 mL liquid monomer, one can add 1 g of tobramycin antibiotic to reduce the chance of disc space infection.5,25,42,43 Some authors, including ourselves, recommend not adding antibiotics to PMMA unless the patient is immunocompromised.6,17

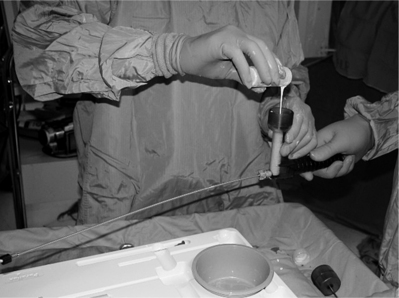

While one is mixing the cement, an assistant connects the long, flexible tube for delivery to the injector barrel. The bone cement preparation is mixed until a doughy, cohesive consistency (similar to toothpaste) is obtained. We delay the polymerization process by cooling the polymer in the refrigerator for an hour before the procedure and this gives additional working time.6,44

In limited circumstances, slow-set cement Cranioplastic type 1 Slow Set (Codman/Johnson & Johnson, Berkshire, UK), at room temperature can be used.6,35 Rapid-set material has the advantage as it rapidly sets in case of leaks, as seen with these procedures. If a cement leak is observed on fluoroscopy, one can stop for a few minutes till the fast cement hardens and blocks that area. As the leaking area is blocked by the hardening cement, more cement may be re-injected. One should look for cement flowing into the opposite direction to the area where the previous cement had already hardened. The cement will rapidly polymerize and will plug the leak in 1–2 minutes and further cement can be injected, which is not possible with slow-setting cement. In addition, slow-setting cement stays liquid longer in the body and thus could potentially leak for a longer time and may leak along the needle tract when the needle is pulled out.6

Once mixing is completed, the bone cement is slowly poured into the injector tube (Fig. 32.9). The injector device is attached and rotated till the cement starts pouring from the tip of the flexible tube (Figs 32.10, 32.11). One can see the consistency of the cement at the end (Fig. 32.12). The flexible tube is connected to the needle inserted earlier into the vertebral body (Fig. 32.13).

Vital signs should be monitored looking for hypotension, as cement injection has been known to cause hypotension in patients undergoing joint replacement surgery.45,46

The injection of cement is stopped whenever epidural or paravertebral opacification is observed or when the cement reaches the dorsal quarter of the vertebral body.3 If extravasation of cement is seen, further injection of cement is stopped. The extravasation is evaluated in both AP and lateral views. If it is considered safe to proceed with the procedure, the needle position should be adjusted. Another needle can also be placed from the contralateral pedicle.

Postprocedure

The cement polymerizes in 1 hour and the patient remain recumbent in supine position for that duration. The patient may be discharged after an hour of monitoring.5 At our center, we discharge patients after keeping them for 1 hour postprocedure, or if medically required we admit them overnight.

Multiple compressions

Multiple-level vertebral compression fractures may be treated by percutaneous vertebroplasty. It is less cumbersome to stagger needles by alternating between right and left pedicles.2 However, there may be additional stress on the adjacent vertebrae.49 If there are multiple compression fractures, one should treat the most painful fracture first.1 No more than two should be treated on a particular day. It is the authors’ preference to treat a single vertebral fracture per day to ensure monomer toxicity risk is minimized. Incidence of venous extravasation of cement or fat50 increases with multiple-level treatment.

AVOIDANCE OF COMPLICATIONS

The complications are minimal if precautions are taken.52

Leakage of cement

Leakage of cement can cause neurologic injury or pulmonary emboli.53–56 One can, however, prevent cement leaks by using high-resolution fluoroscopy (or rarely CT), adequate cement opacification, and by interrupting or terminating the procedure on first recognition of a leak. Biplanar fluoroscopy is not required but does make visualization in two projections simpler and faster. One must visualize the vertebra in two planes numerous times. The authors use a uniplanar machine which is rotated at every step to obtain anteroposterior and lateral views. Sterile barium sulfate is added to bring the barium quantity to 30% by weight, making the cement opaque for visualization under fluoroscopy. Presently, FDA approved premixed cement for vertebroplasty is available commercially. Terminating injection when early leakage of cement is visualized limits the size of the leak and usually prevents it from becoming significant. Venography has been used to observe leakage but it does not accurately predict the leak of cement.14 If there is leakage into the spinal canal with neurological deficit, a neurosurgeon or spinal surgeon should be consulted.57,58

Pain exacerbation

At times the pain may exacerbate due to local ischemia or increased pressure. A CT scan be immediately obtained to ensure no leakage. Otherwise, the pain usually resolves in a few hours or a few days.14 We discharge all patients with narcotic medication (oxycodone) to be used on an as-needed basis. If radicular pain occurs secondary to leakage into the neural foramen, within 10–20 minutes we inject 10 cc of 0.2% lidocaine followed by 100–200 cc of pressurized saline perfusion.59,60 During the injection, the patient may feel some pressure, but the surgeon should be aware of this and slow or stop injection if significant radicular pain occurs.

Bleeding

The cannula is removed after adequate filling of the vertebra. Venous bleeding may be observed at the needle entry sites and local pressure for 3–5 minutes will minimize the bleeding.6

Occupational dose mitigation

Secondary radiation, particularly scatter radiation from the patient and leakage radiation from the radiograph tube, is the primary source of operator and medical staff exposure. Techniques to reduce exposure to the operator include shielding devices, which are placed directly on the patient to provide maximum shielding to the operator’s hands and upper body. Additionally, a lead apron can be placed between the surgeon and the patient. Exposure on injecting cement with 1 mL syringe and vertebroplasty kit is the same.61

Polymethyl methacrylate vapor levels to which medical personnel are exposed during percutaneous vertebroplasty are well below the level typically considered hazardous. However, it is important to note that some individuals may experience adverse effects, such as asthma, coughing, nausea, and decreased appetite, when exposed to levels6 typically considered to be acceptable.62–64

1 Stallmeyer MJ, Zoarski GH, Obuchowski AM. Optimizing patient selection in percutaneous vertebroplasty. J Vascul Intervent Radiol. 2003;14(6):683-696.

2 Amar AP, Larsen DW, Esnaashari N, et al. Percutaneous transpedicular polymethylmethacrylate vertebroplasty for the treatment of spinal compression fractures. Neurosurgery. 2001;49(5):1105-1114. discussion 1114–1115

3 Gangi A, Guth S, Imbert JP, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: indications, technique, and results. Radiographics. 2003;23(2):e10.

4 Maynard AS, Jensen ME, Schweickert PA, et al. Value of bone scan imaging in predicting pain relief from percutaneous vertebroplasty in osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(10):1807-1812.

5 Hodler J, Peck D, Gilula LA. Midterm outcome after vertebroplasty: predictive value of technical and patient-related factors. Radiology. 2003;227(3):662-668.

6 Mathis JM, Wong W. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: technical considerations. J Vascul Intervent Radiol. 2003;14(8):953-960.

7 Kallmes DF, Jensen ME. Percutaneous vertebroplasty [Review]. Radiology. 2003;229(1):27-36.

8 Jensen ME, Evans AJ, Mathis JM, et al. Percutaneous polymethylmethacrylate vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral body compression fractures: technical aspects. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(10):1897-1904.

9 Kaufmann TJ, Jensen ME, Schweickert PA, et al. Age of fracture and clinical outcomes of percutaneous vertebroplasty. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(10):1860-1863.

10 Barr JD, Barr MS, Lemley TJ, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty for pain relief and spinal stabilization [see comment]. Spine. 2000;25(8):923-928.

11 Fourney DR, Schomer DF, Nader R, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty for painful vertebral body fractures in cancer patients. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(1 Suppl):21-30.

12 White SM. Anaesthesia for percutaneous vertebroplasty. Anaesthesia. 2002;57(12):1229-1230.

13 Brown DB, Gilula LA, Sehgal M, et al. Treatment of chronic symptomatic vertebral compression fractures with percutaneous vertebroplasty. Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182(2):319-322.

14 Mathis JM. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: complication avoidance and technique optimization. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(8):1697-1706.

15 Sesay M, Dousset V, Liguoro D, et al. Intraosseous lidocaine provides effective analgesia for percutaneous vertebroplasty of osteoporotic fractures. Can J Anaesthes. 2002;49(2):137-143.

16 Gangi A, Kastler BA, Dietemann JL. Percutaneous vertebroplasty guided by a combination of CT and fluoroscopy. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(1):83-86.

17 Peters KR, Guiot BH, Martin PA, et al. Vertebroplasty for osteoporotic compression fractures: current practice and evolving techniques. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(5 Suppl):96-103.

18 Gailloud P, Martin JB, Olivi A, et al. Transoral vertebroplasty for a fractured C2 aneurysmal bone cyst [Case Reports. Letter]. J Vascul Intervent Radiol. 2002;13(3):340-341.

19 Martin JB, Gailloud P, Dietrich PY, et al. Direct transoral approach to C2 for percutaneous vertebroplasty. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2002;25(6):517-519.

20 Cotten A, Boutry N, Cortet B, Assaker R, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: state of the art. Radiographics. 1998;18(2):311-320. discussion 320–323

21 Galibert P, Deramond H, Rosat P, et al. [Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral angioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty]. [French]. Neuro-Chirurgie. 1987;33(2):166-168.

22 Appel NB, Gilula LA. ‘Bull’s-eye’ modification for transpedicular biopsy and vertebroplasty. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(6):1387-1389.

23 Cortet B, Cotten A, Boutry N, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty in the treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures: an open prospective study. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(10):2222-2228.

24 Deramond H, Depriester C, Galibert P, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty with polymethylmethacrylate. Technique, indications, and results. Radiol Clin N Am. 1998;36(3):533-546.

25 Kallmes DF, Schweickert PA, Marx WF, et al. Vertebroplasty in the mid- and upper thoracic spine. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(7):1117-1120.

26 Kim AK, Jensen ME, Dion JE, et al. Unilateral transpedicular percutaneous vertebroplasty: initial experience. Radiology. 2002;222(3):737-741.

27 Martin JB, Wetzel SG, Seium Y, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty in metastatic disease: transpedicular access and treatment of lysed pedicles – initial experience. Radiology. 2003;229(2):593-597.

28 Garfin SR, Yuan HA, Reiley MA. New technologies in spine: kyphoplasty and vertebroplasty for the treatment of painful osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine. 2001;26(14):1511-1515.

29 http://sis.windhover.com/windbuy/lpext.dll/windbuy/iv/2001/2001800190.htm

30 Al-Assir I, Perez-Higueras A, Florensa J, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: a special syringe for cement injection. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:159-161.

31 Heini PF, Allred C. The use of a side-opening injection cannula in vertebroplasty: a technical note. Spine. 2002;27(1):105-109.

32 Murphy KJ, Lin DD, Khan AA, et al. Multilevel vertebroplasty via a single pedicular approach using a curved 13-gauge needle: technical note. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2002;53(5):293-295.

33 Schallen EH, Gilula LA. Vertebroplasty: reusable flange converter with hub lock for injection of polymethylmethacrylate with screw-plunger syringe. Radiology. 2002;222(3):851-855.

34 Minart D, Vallee JN, Cormier E, et al. Percutaneous coaxial transpedicular biopsy of vertebral body lesions during vertebroplasty. Neuroradiology. 2001;43(5):409-412.

35 McGraw JK, Heatwole EV, Strnad BT, et al. Predictive value of intraosseous venography before percutaneous vertebroplasty [see comment]. J Vascul Intervent Radiol. 2002;13(2 Pt 1):149-153.

36 Peh WC, Gilula LA. Additional value of a modified method of intraosseous venography during percutaneous vertebroplasty. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(1):87-91.

37 Gaughen JRJr, Jensen ME, Schweickert PA, et al. The therapeutic benefit of repeat percutaneous vertebroplasty at previously treated vertebral levels [see comment]. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(10):1657-1661.

38 Phillips FM. Minimally invasive treatments of osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Spine. 2003;28(15):S45-S53.

39 Vasconcelos C, Gailloud P, Beauchamp NJ, et al. Is percutaneous vertebroplasty without pretreatment venography safe? Evaluation of 205 consecutives procedures. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(6):913-917.

40 Wong W, Mathis J. Is intraosseous venography a significant safety measure in performance of vertebroplasty? J Vascul Intervent Radiol. 2002;13(2 Pt 1):137-138.

41 Mathis JM, Barr JD, Belkoff SM, et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: a developing standard of care for vertebral compression fractures. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22(2):373-381.

42 Hiwatashi A, Moritani T, Numaguchi Y, et al. Increase in vertebral body height after vertebroplasty. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(2):185-189.

43 Peh WC, Gilula LA. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: indications, contraindications, and technique. Br J Radiol. 2003;76(901):69-75.

44 Chavali R, Resijek R, Knight SK, et al. Extending polymerization time of polymethylmethacrylate cement in percutaneous vertebroplasty with ice bath cooling. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(3):545-546.

45 Kaufmann TJ, et al. Cardiovascular effects of polymethylmethacrylate use in percutaneous vertebroplasty [see comment]. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(4):601-604.

46 Vasconcelos C, Gailloud P, Martin JB, et al. Transient arterial hypotension induced by polymethylmethacrylate injection during percutaneous vertebroplasty. J Vascul Intervent Radiol. 2001;12(8):1001-1002.

47 Belkoff SM, Mathis JM, Jasper LE, et al. An ex vivo biomechanical evaluation of a hydroxyapatite cement for use with vertebroplasty. Spine. 2001;26(14):1542-1546.

48 Liebschner MA, Rosenberg WS, Keaveny TM. Effects of bone cement volume and distribution on vertebral stiffness after vertebroplasty. Spine. 2001;26(14):1547-1554.

49 Berlemann U, Ferguson SJ, Nolte LP, et al. Adjacent vertebral failure after vertebroplasty. A biomechanical investigation. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2002;84:748-752.

50 Aebli N, Krebs J, Davis G, et al. Fat embolism and acute hypotension during vertebroplasty: an experimental study in sheep. Spine. 2002;27:460-466.

51 Gilula L. Is insufficient use of polymethylmethacrylate a cause for vertebroplasty failure necessitating repeat vertebroplasty? [comment]. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(10):2120-2121. author reply 2121–2122

52 McGraw JK, Cardella J, Barr JD, et al. SIR Standards of Practice Committee. Society of Interventional Radiology quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous vertebroplasty. J Vascul Intervent Radiol. 2003;14(7):827-831.

53 Harrington KD. Major neurological complications following percutaneous vertebroplasty with polymethylmethacrylate: a case report [see comment]. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2001;83-A(7):1070-1073.

54 Kang JD, An H, Boden S, et al. Cement augmentation of osteoporotic compression fractures and intraoperative navigation: summary statement. Spine. 2003;28(15):S62-S63.

55 Mousavi P, Roth S, Finkelstein J, et al. Volumetric quantification of cement leakage following percutaneous vertebroplasty in metastatic and osteoporotic vertebrae. J Neurosurg. 2003;99(1 Suppl):56-59.

56 Yeom JS, Kim WJ, Choy WS, et al. Leakage of cement in percutaneous transpedicular vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic compression fractures. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 2003;85(1):83-89.

57 Lee B-J, Lee S-R, Yoo T-Y. Paraplegia as a complication of percutaneous vertebroplasty with polymethylmethacrylate: a case report. Spine. 2002;27(19):E419-E422.

58 Shapiro S, Abel T, Purvines S. Surgical removal of epidural and intradural polymethylmethacrylate extravasation complicating percutaneous vertebroplasty for an osteoporotic lumbar compression fracture. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(1 Suppl):90-92.

59 Jarvik JG, Kallmes DF, Mirza SK. Vertebroplasty: learning more, but not enough. Spine. 2003;28(14):1487-1489.

60 Kelekis AD, Martin J-B, Somon T, et al. Radicular pain after vertebroplasty: compression or irritation of the nerve root? Initial experience with the ‘cooling system.’. Spine. 2003;28(14):E265-E269.

61 Kallmes DF, Roy SS, Piccolo RG, et al. Radiation dose to the operator during vertebroplasty: prospective comparison of the use of 1-cc syringes versus an injection device. Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24(6):1257-1260.

62 Cloft HJ, Easton DN, Jensen ME, et al. Exposure of medical personnel to methylmethacrylate vapor during percutaneous vertebroplasty. Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20(2):352-353.

63 Kirby BS, Doyle A, Gilula LA. Acute bronchospasm due to exposure to polymethylmethacrylate vapors during percutaneous vertebroplasty. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(2):543-544.

64 Nimmagadda U, Salem MR. Acute bronchospasm associated with methylmethacrylate cement. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:1290-1291.