35 Vertebroplasty

KEY POINTS

Introduction

It is estimated that 1.4 million vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) occur annually, causing pain and disability in patients worldwide.1 The lifetime risk of a vertebral compression fracture in White women is 16%; in men, it is 5%. Historically, treatment of these fractures has been limited to analgesics, bed rest, and bracing. However, recently the development of vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty has provided physicians with additional treatment options for select vertebral compression fractures.

History of Vertebroplasty

Vertebroplasty was initially developed as an open procedure designed to augment the purchase of pedicle screws and to fill large voids from tumor resection. In 1984, however, at the University Hospital of Amiens, France, Galibert and Deramond performed the first documented percutaneous vertebroplasty.2 The patient presented with severe cervical pain, and imaging demonstrated a large vertebral hemangioma encompassing the entire vertebral body of C2 with extension into the epidural space. After performing a C2 laminectomy to excise the epidural component of the lesion, a 15-gauge needle was inserted into the C2 vertebral body via an anterolateral approach, allowing injection of cement for structural reinforcement. The document of this case, as published in 1987, reports complete pain relief in this patient. Physicians at University Hospital Lyon continued to refine the percutaneous vertebroplasty technique as well as to expand its indications, using 18-gauge needles to inject polymethylmethacrylate(PMMA) into four patients with compression fractures. Since then, its popularity has spread dramatically.

Patient Selection/Indications

Bone scintigraphy may be employed to detect a relatively recent fracture in patients who cannot tolerate an MRI. Increased radiotracer uptake has been correlated with positive clinical response to vertebroplasty. However, this technique is limited by the fact that the bone scan may show increased tracer uptake for up to 12 months after fracture. Thus this method must be correlated with corresponding anatomic imaging.

After a careful history, physical examination, and assessment of radiographic imaging, the physician must then determine not only that the source of the patient’s pain is indeed a VCF, but also that this fracture is amenable to vertebroplasty. The primary indication for vertebroplasty is the alleviation of pain associated with a VCF due to osteoporosis or tumor. Repeated studies have demonstrated superior pain relief with treatment of acute or subacute fractures. Perhaps most notable is the non–industry-sponsored, double-cohort by Alvarez et al3, which compared vertebroplasty to nonoperative treatment for VCFs. He found statistically significant differences at 3 months follow-up. Wardlaw et al4 published a randomized controlled trial comparing balloon kyphoplasty with nonsurgical care for VCFs. He too demonstrated a significant improvement in the intervention group at 1 month. Some now advocate the treatment of VCF within days of injury if the pain is so severe as to require parenteral narcotics and hospitalization. Late treatment, 6 months to years after the initial injury, is less likely to completely relieve pain, but symptomatic improvement has been noted in some studies.

Technique

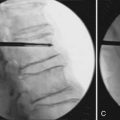

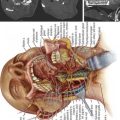

Procedure

Once the approach has been chosen, local anesthesia should be injected into the skin and subcutaneous tissue along the expected needle tract; The periosteum of the bone at its entry site should also be injected. Next, a small skin incision is made. The trocar and cannula are then introduced through the skin incision and worked through the subcutaneous tissues down to the level of the periosteum. The cannula and trocar should then be passed into the bone. In osteoporotic bone, this can usually be done manually. In neoplastic disease, the normal bone may be dense, necessitating the use of a mallet for appropriate placement. Ultimately the tip of the needle should be positioned beyond the midpoint of the vertebral body as viewed on the lateral projection.

Injection Materials

In the first vertebroplasty procedures, PMMA bone cement mixed with a contrast agent, typically barium sulfate, was injected into vertebral bodies under image guidance.5 Since Charnley first reported its use in 1960, PMMA bone cements have been used by orthopedic surgeons for the fixation of both plastic and metal components in joint replacement and, less often, in the stabilization of pathological fracture. Early studies showed maintenance of the bond between the prosthesis and the PMMA with no evidence of harmful systemic effects. Thus, PMMA is now widely used throughout orthopedics.

The limitations of PMMA cement have led researchers to seek alternative filler materials. The primary characteristic of these novel products is their osteoconductivity. The best studied of these synthetic bone substitutes is the class of calcium phosphate cements. As osteoconductive agents, these possess the potential for resorption of cement and replacement with new bone, effectively restoring vertebral body bone mass. Studies have shown evidence of osteoclastic resorption of the cement and fragmentation with vascular invasions and bony ingrowth.6 Histologic results show direct bone apposition suggestive of remodeling. Like PMMA, calcium phosphate fillers initially function as bulk-filling agents. However, due to their osteoconductive capabilities, their strength is gradually reinforced by new bone formation. Biomechanical testing of calcium phosphate cements has verified their ability to restore the mechanical integrity of the vertebral body.

Complications

In a patient with an osteoporotic VCF treated by percutaneous vertebroplasty, the incidence of complication necessitating surgical intervention is estimated to be less than 1%.7 In patients with neoplastic VCF, 2.7% to 5.4% will require surgery to manage a complication of vertebroplasty. In this population, less significant complications are estimated to occur in up to 10% of patients. This increased risk is likely due to an increased risk of cement extravasation due to cortical breaks in the vertebral body.

Extravasation of cement into the epidural veins can cause a cement embolism to the lung. As in hip and knee arthroplasty, the pressurized injection of cement into the vertebral body can also cause a fat embolism. While the majority of these emboli are asymptomatic, they can be particularly problematic in patients with pre existing pulmonary conditions, such as COPD. Further respiratory complications can be induced by inaccurate placement of the needle, which can cause a pneumothorax. As in all invasive procedures, there is a risk of bleeding, which is more common in the parapedicular approach due to the large paraspinous vessels. Infection is exceedingly rare. Finally, there have been reports of deaths attributed to vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. These seem to be due to severe cement allergy or pulmonary failure in patients with preoperative pulmonary compromise.

Nejm Randomized Controlled Trials

The August 6, 2009 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine presented two randomized studies seeking to assess the efficacy of vertebroplasty for pain relief in osteoporotic vertebral fractures. In Buchbinder et al,8 enrolled patients with one or two painful osteoporotic VCFs less than 12 months old and unhealed, as confirmed by MRI, were randomized to either vertbroplasty or a sham procedure. Outcomes were assessed up to 6 months. They concluded that there was “no beneficial effect of vertebroplasty over a sham procedure at 1 week or at 1, 3, or 6 months among patients with painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures.” Kallmes et al9 randomly assigned 131 patients with one, two, or three painful osteoporotic VCFs thought to be less than 1 year old to either vertebroplasty or a similar sham procedure. Outcomes were assessed up to 3 months. Of note, MRI was only employed if the age of the fracture was “unknown.” This study concludes that “improvements in pain and pain-related disability associated with osteoporotic compression fractures in patients treated with vertebroplasty were similar to improvements in a control group.”

Upon further examination of these studies, several important criticisms have been raised.10 These are discussed below.

1. Johnell O., Kanis J.A. An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos. Int. 2006;17:1726-1733.

2. Galibert P., Deramond H., et al. Preliminary note on the treatment of vertebral hemangioma by percutaneous acrylic vertebroplasty. Neurochirurgie. 1987;33(2):166-168.

3. Alvarez L., Alcaraz M., et al. Percutaneous vertebroplasty: functional improvement in patients with osteoporotic compression fractures. Spine. 2006;31(10):1113-1118.

4. Wardlaw D., Cummings S.R., et al. Efficacy and safety of balloon kyphoplasty compared with non-surgical care for vertebral compression fracture: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9668):1016-1024.

5. Lieberman I.H., Togawa D., Kayanja M.M. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty: filler materials. Spine J. 2005;5(6 Suppl):305S-316S.

6. Turner T.M., et al. Vertebroplasty comparing injectable calcium phosphate cement compared with polymethylmethacrylate in a unique canine vertebral body large defect model. Spine J. 2008;8(3):482-487.

7. Mathis J.M., Deramond H., Belkoff S.M. Percutaneous vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty, ed 2. New York: Springer; 2006.

8. Buchbinder R., Osborne R.H., et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for painful osteoporotic vertebral fractures. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2009;361(6):557-568.

9. Kallmes D.F., Comstock B.A., et al. A randomized trial of vertebroplasty for osteoporotic spinal fractures. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2009;361(6):569-579.

10. North American Spine Society: Newly released vertebroplasty RCTs: a tale of two trials: www.spine.org/Documents/NASSComment_on_Vertebroplasty.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2010.