Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is an allergic ocular surface disease that affects primarily the conjunctiva and cornea and is characterized by chronic ocular surface inflammation. The chronicity of VKC can lead to debilitating ocular surface disease, with myriad potential complications, that may permanently affect vision. The name ‘vernal’ itself implies spring and youth, reflecting two common characteristics of VKC. It primarily affects children, although it may rarely occur in adults. In addition, the disease course is often seasonal with exacerbations in the warmer months (typically the spring), but in some patients it can become a chronic condition and occur throughout the year.1 Males are affected more than females; however, one series reports a female preponderance in cases.2 The diagnosis of VKC is clinical and is based on typical signs and symptoms. The classic signs include conjunctival hyperemia, tarsal papillae, limbal papillae, and ropy mucous discharge. Symptoms of VKC are itching, photophobia, and tearing. There may also be pain if the cornea is involved. The disorder is found with varying frequency in all geographic areas, but has a higher incidence in warmer climates. VKC has been described in the ophthalmic literature for over 150 years. The condition has been referred to in the literature by many names, including spring catarrh, phlyctaena palladia, circumcorneal hypertrophy and conjunctivitis verrucosa, but the current nomenclature of vernal keratoconjunctivitis is now almost universally used.3

The precise etiology and pathogenesis of VKC are still unknown. There have been many clinical and laboratory studies performed in recent years in an attempt to answer these questions. While it is established that VKC is an IgE- and Th2-mediated allergic condition, it is clear that the simplified concept of a type I allergic hypersensitivity reaction does not fully describe the complex immune process involved in VKC.4–6

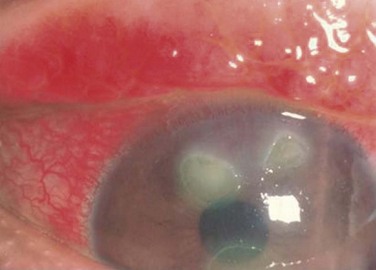

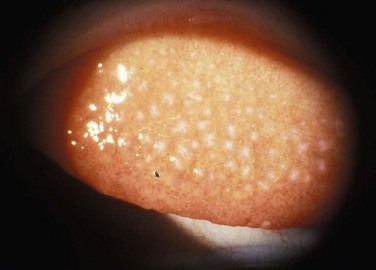

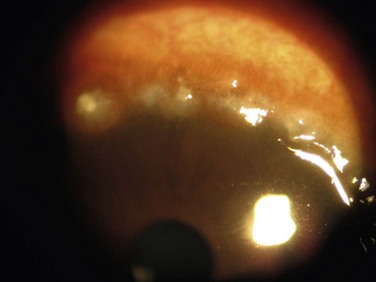

VKC may affect the superior palpebral conjunctiva, the bulbar conjunctiva, or both, with patients exhibiting two forms of disease: palpebral vernal and limbal vernal. The inferior palpebral conjunctiva is less often involved with VKC. In the palpebral form, the superior tarsal conjunctiva is the primary location of pathology, making ptosis a common associated finding of palpebral VKC. Papillae of various sizes develop on the superior tarsal conjunctiva (Fig. 14.1). As the disease progresses, the papillae may coalesce into larger lesions referred to as ‘cobblestone’ or ‘paving-stone’ papillae (Fig. 14.2). Deep furrows are seen in between the papillae. These large papillae may cause mechanical damage to the cornea. The discharge is thick and ropy and characteristically has a dirty white or cream color. Microscopic examination of the discharge shows large numbers of eosinophils, mononuclear, and polymorphonuclear inflammatory cells.1 Scarring of the conjunctiva is not seen in VKC.

Figure 14.1 Slit lamp photograph of the upper tarsal palpebral conjunctiva, demonstrating a diffuse papillary reaction.

Figure 14.2 Giant papillae of the upper tarsal palpebral conjunctiva. The classic cobblestone appearance of VKC.

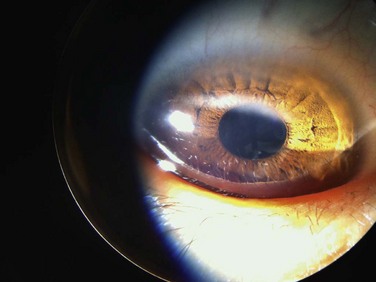

In the limbal form, there is a broadening and opacification of the limbus. This can produce a semitransparent, thickened appearance of the limbus. These signs are often seen first in the superior limbus, but can spread 360 degrees. Discrete yellow or gray nodules may appear in the thickened limbus. In severe cases, these nodules can become confluent. White, punctate lesions known as Horner–Trantas dots may develop in the hypertrophied limbus (Fig. 14.3).

Figure 14.3 Slit lamp photograph of Horner–Trantas, dots characteristic of limbal vernal keratoconjunctivitis.

Either form of VKC can affect the cornea, with the earliest corneal manifestation typically found as a superficial punctate keratitis, referred to as keratitis of Tobgy.1 It can progress to multiple, discrete, dull gray points of epithelial irregularity and degeneration, which stain with fluorescein or rose bengal. These spots may become confluent and coalesce into a corneal erosion or ulcer, referred to as a vernal shield ulcer (Fig. 14.4). The ulcer is typically indolent, characteristically oval in shape, and most commonly found in the upper half of the cornea. The ulcer is often shallow with white edges. A grayish opacification of Bowman’s membrane may develop which will eventually harden into a gray plaque in the base of the ulcer. Often, plaque removal is needed to promote healing of the ulcer. After an ulcer is healed, corneal neovascularization and scarring are often seen.1,7 Another potential complication of the shield ulcer is secondary bacterial or fungal infection by colonized pathogens.8

Another corneal manifestation of VKC is pseudogerontoxon, which resembles a segment of arcus senilis or gerontoxon, and is seen in many individuals with limbal VKC. The lesion is typically found a few millimeters anterior to the limbus in the midperipheral cornea and is often arcuate in pattern. It may be unifocal or multifocal (Fig. 14.5). It is an important clinical finding because pseudogerontoxon is often the only clinical evidence of previous allergic eye disease.9

Demographics

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis is predominantly a disease of children and adolescents. Two large case series from central Italy, where there is a relatively high incidence of VKC, have reported the mean age at diagnosis as between 6.8 ± 5years and 11 ± 5years.10,11 Only 4% of newly diagnosed patients were older than 20 at the time of initial diagnosis.10 There are more males with VKC than females. Multiple case series have reported a male to female ratio of approximately 3 : 1.10,11 Interestingly, the higher number of males affected seems to only be present in children and adolescents. When looking at adults with VKC over the age of 20 years, the male to female ratio is 1 : 1.11 Estrogen and progesterone receptors are present in the epithelium and subepithelium of patients with VKC, while not normally present in healthy epithelium. The role these hormonal receptors play in VKC is not known.12

Prevalence

The prevalence of vernal keratoconjunctivitis varies by geographic region. The disease is most prevalent in warm climates. In geographic regions with temperate seasonal change, a relapsing pattern of VKC is often seen, with flare-ups occurring in the spring and summer months, and remission of symptoms in the cooler winter months. In climates that remain hot all year round, a perennial form of VKC is commonly seen. This is not an absolute finding, and individual patients with either relapsing or perennial VKC are seen in any climate. The estimated overall prevalence of VKC is 3.2/10 000 across all of western Europe. A higher prevalence is seen in Italy (27.8/10 000) where the climate is warmer, while a lower prevalence of VKC is seen in Norway (1.9/10 000) where the climate is cooler.13

Co-Morbid Conditions

Since VKC is an allergic condition, other allergic co-morbid conditions may be associated. A family history of atopic disease is seen in 48% of patients with VKC.11 Among patients with VKC, 15–64% also have asthma, 30–49% also have allergic rhinitis, and 16–24% also have eczema.10,11 Not all patients with VKC have co-morbid conditions. VKC is the only clinical issue in 59% of patients.11 Allergen skin prick testing for common allergens is positive in 44–58% of VKC patients. Specific serum IgE levels are positive in 57% of VKC patients,10 and are increased in VKC patients compared to serum IgE levels in normal controls.11 Other than allergic conditions, keratoconus is the disease most commonly associated with VKC. Prevalence of clinical keratoconus in VKC patients is 2–9%. In a large cohort of patients with VKC, 27% were identified as having keratoconus based on videokeratography maps.14 Eye rubbing, which is common among patients with VKC, due to chronic eye itching, has been proposed as an explanation for the high rate of keratoconus in this cohort.15 Iatrogenic cataracts from steroid use, as well as steroid-induced glaucoma complications, have been reported. Bacterial keratitis and shield ulcers are seen in 10% of patients with VKC and these are typically the most severe cases. Fungal keratitis is rare, but has been reported in VKC.16

Genetics

To date, no specific genotype has been demonstrated to have a relationship with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Current research is investigating this question. The presence of eosinophilia, increased expression of cytokines, and other cellular mediators, including increased CD4 lymphocyte cells in the epithelium and subepithelium of affected patients suggests VKC may be associated with up-regulation of the cytokine gene cluster on chromosome 5q. This gene regulates production of IL-3, -4, -5, granulocyte/macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), type 2 T-helper cells, growth of mast cells and eosinophils and production of IgE, all of which are seen in the pathology of VKC.17

Clinical Features

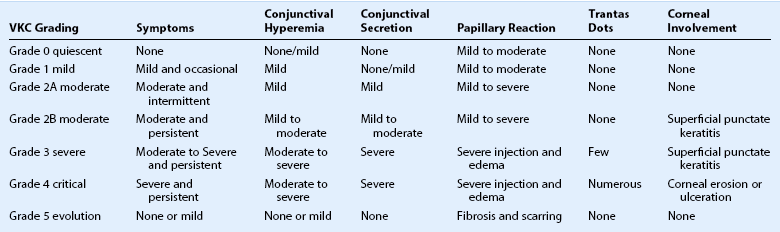

The classic and most constant clinical symptoms of vernal keratoconjunctivitis are itching, redness, photophobia, and tearing; these are all seen in > 90% of patients with VKC.11 The tarsal form of the disease is the most common, with superior tarsal papillae seen in 44–83% of patients. Limbal papillae are seen in 8–11%, and a mixed clinical picture is found in 9–46% of patients with VKC. Giant cobblestone papillae occur in 16% of patients.10,11,14 Ninety-eight percent of cases are bilateral.11 Other common signs include Horner–Trantas dots in 15% of reported cases and mucous discharge in 53% of reported cases.11 Treatment of VKC is guided by the severity of symptoms. The response to treatment is variable. In one case series, with long-term follow up of greater than 3 years, 27% of patients had a complete resolution, 35.4% showed improvement but mild to moderate persistence of symptoms, and 32% had no change in signs or symptoms as a response to therapy. Severe worsening involving visual loss is rare and is seen in cases with ulcerative keratitis. 6% of patients had a loss of two or more lines of best corrected vision due to corneal scarring and neovascularization.11 A clinical grading system has been developed to help standardize communication regarding clinical features and severity (Table 14.1).

Table 14.1

Clinical Grading of Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis

Adapted from Bonini S, Sacchetti M, Mantelli F, et al. Clinical grading of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;7:436–41.

Pathophysiology

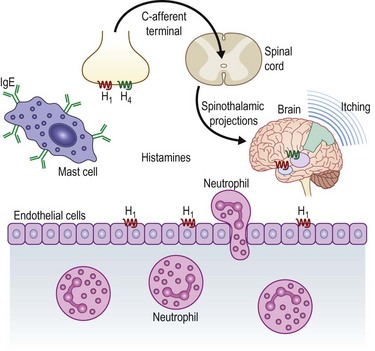

Many immunohistochemical and molecular biological studies have demonstrated that there are a multitude of cellular signaling pathways involved in the allergic response in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. The mechanisms governing the coordination and recruitment of inflammatory cells in the conjunctiva of patients with VKC is complex and not fully understood. As with other allergic conditions, patients with VKC display signs of a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction. In this acute allergic reaction, allergens bind to IgE on mast cells and basophils, stimulating degranulation and release of cytokines and histamine. Levels of IgE may be elevated in the serum and tears of patients with VKC when compared to normal controls.18,19 Concentration of histamine in tears has been shown to be higher in patients with VKC compared to controls. This may be due to reduced inactivation of histamine by histaminase and increased local production by basal and mast cells.20 The theory of a type 1 hypersensitivity reaction alone cannot explain the pathology of VKC. Fifty percent of patients with VKC had negative skin tests to common allergens.11 In addition, tear samples of VKC patients, as well as conjunctival biopsies, demonstrate many cytokines and immune cells.4 Figure 14.6 demonstrates a schematic diagram of the allergic cascade responsible for VKC.

Activated helper T cells, mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, macrophages, plasma cells, and fibroblasts are found in the conjunctiva of patients with VKC. The immune cells are often organized as small lymphoid follicles without a germinal center. Th2 lymphocytes and their cytokines IL-3, IL-4, and IL-5 are found at elevated levels in tears of VKC patients.21 Research has shown that Th2 cells are important in the pathophysiology of VKC, while Th1 lymphocytes and the cytokines produced by these cells, IL-2, interferon gamma, and tumor necrosis factor beta (TNF-β), are not found at elevated levels in VKC patients.22 Thus, it is believed that Th2 cells are important in mediating the inflammatory response in VKC.

Chemokines are involved in leukocyte recruitment and chemotaxis in the inflammatory response. Chemokines bind to G-protein coupled receptors and signal via secondary messengers to alter cell behavior. Monocyte chemotactic protein (MCP), regulated upon activation, normal T cells expressed and secreted (RANTES), exotaxin, and macrophage inhibitory protein (MIP), may have an important role in regulating the allergic response in VKC.23

Mast cell-released proteases, tryptase, and chymase are elevated in tears of patients with VKC.24 Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are extracellular enzymes that are active in promotion of inflammation and degradation of the extracellular matrix. MMP-1, -3, -9, and -13 have been found in high concentration of conjunctival biopsies of VKC patients.25 Transforming growth factor (TGF) β1, β2 and their intracellular downstream effector proteins, Sma- and Mad- related protein (Smad) -2, -3 are increased in the stroma of VKC patients, compared to normal controls.26 Both nerve growth factor (NGF) and substance P, which is modulated by NGF, are found at increased plasma levels in VKC patients, compared to controls.27 Immunohistochemical study of the collagen in the conjunctival epithelium and stroma of patients with VKC shows increased amounts of type I and III collagen, as well as a thickened basement membrane, consisting of type IV collagen.28,29

Corneal confocal microscopy has been used to examine morphologic changes of the cornea in vivo in patients with VKC. Increased numbers of activated keratocytes and inflammatory cells are seen in the anterior stroma of VKC patients, compared to normal controls. Also, increased epithelial cell diameter and reflectivity is seen in the superficial epithelium of the cornea.30 The combined effect of these cellular mediators is promotion of inflammation, stimulation of fibroblast growth and proliferation, and increased collagen production in the conjunctival and corneal stroma.31 When chronic, these changes lead to tissue remodeling and scarring.

Treatment

There are many options for pharmacologic therapy for VKC. Topical vasoconstrictors, such as naphazoline and tetrahydrozoline are available over the counter and commonly used. Through vasoconstriction, they decrease conjunctival redness temporarily: however, rebound hyperemia with prolonged use limits their utility. Antiallergy eye drops, such as antihistamines and mast cell stabilizers, are the primary agents used to treat the chronic symptoms of itching, redness and irritation associated with mild to moderate VKC. Histamine released by mast cells found in submucosal tissue, is an important mediator in a type I allergic hypersensitivity reaction. Levocabastine 0.05%, a selective histamine (H1) receptor antagonist, has been proven effective for treating ocular allergic symptoms of VKC.32,33 Extensive research has documented the efficacy of mast cell stabilizers in treatment of VKC.34–37 Mast cell stabilizers, including cromolyn sodium 4%, nedocromil sodium 2%, and lodoxamide 0.1%, work by inhibiting mast cell degranulation, suppressing the inflammatory cascade resulting from release of inflammatory mediators, including histamine from mast cells.

Newer topical agents combine the anti-inflammatory effect of a H1 receptor antagonist and a mast cell stabilizer. These medications, including olopatadine 0.2%, epinastine, 0.05%, ketotifen 0.025%, and alcaftadine 0.25%, have been studied extensively for use in treatment of allergic conjunctivitis and vernal keratoconjunctivitis.38 They are suitable for treatment of mild chronic symptoms of VKC, due to the low side effect profile and ease of use, with daily or twice-daily dosing. Oral H1 receptor antagonists may also be used to control these symptoms.

Preservative-free topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drops, ketorolac 0.5% and diclofenac 0.1% have been used effectively to treat VKC. Forty percent of patients treated with diclofenac for 120 days showed clinical improvement of symptoms.39 Ketorolac 0.5% was shown to reduce the signs and symptoms of VKC more rapidly than topical cyclosporine 0.5%.40

Stronger anti-inflammatory medication is often required to treat a flare of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Topical corticosteroid eye drops, including fluorometholone 0.1%, loteprednol 0.5%, prednisolone acetate 1%, and dexamethasone phosphate 0.1% are the primary treatment modality for flares of VKC. Fluorometholone 0.1% was shown to be more effective than nedocromil sodium for treating symptoms of severe VKC.41 Due to complications associated with prolonged use, topical corticosteroids should be administered in pulsed dosing with symptom flares and tapered off when symptoms are controlled. Complications of prolonged topical steroid use includes cataract and steroid-induced glaucoma, which have been reported in 2% of patients with VKC.11 In addition, a solution (e.g. prednisolone sodium phosphate) may be preferred to a suspension (e.g. prednisolone acetate) in VKC, due to the adverse mechanical effects of the suspension particles in combination with large papillae. When topical corticosteroid drops are not effective or when a longer duration of the theraputic effect is desired, supratarsal injection of dexamethasone sodium phosphate (2 mg) or triamcinolone acetonide (20 mg) has been shown to improve symptoms.42,43 Similar to corticosteroid drop use, supratarsal corticosteroid injection can cause an increase of intraocular pressure; therefore, it is imperative to monitor the intraocular pressure of patients following treatment.

Cyclosporine A has been studied as another therapeutic option for moderate to severe cases of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cyclosporine produces an anti-inflammatory effect by selectively suppressing the production of interleukin 2 by T lymphocytes. Multiple randomized, placebo controlled trials have demonstrated the effectiveness of cyclosporine A 1–2% at decreasing signs and symptoms of VKC, including itching, tearing, photophobia, conjunctival hyperemia, Trantas dots, and punctate keratitis.44–47 Treatment benefit was noted as early as 2 weeks after treatment onset. Cyclosporine has been used for up to 4 months continuously without significant side effects, other than burning upon administration of the drops. Cyclosporine was not detected in the serum of patients using the drops.47,48 Compared to dexamethasone 0.1%, cyclosporine A 2% was equally effective in reducing signs and symptoms of VKC when used for 1 month.46 Symptoms often recur after cessation of the medication. For patients with moderate to severe VKC experiencing side effects of topical steroids, such as elevated IOP, cyclosporine may be an effective alternative treatment. Cyclosporine A 2% is not commercially available and must be made by a compounding pharmacy. Tacrolimus ointment (0.03%) is another antiinflammatory agent that has been shown effective against VKC by inhibiting the inflammatory actions of T cells.

Mitomycin-C (MMC) 0.01% has been used successfully to treat exacerbations of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis.49,50 It is an antibiotic drug which also acts as a nonselective inhibitor of cell proliferation. To limit toxic effects of the medication to the ocular surface, MMC is used for short intervals, up to 2 weeks and then stopped. The most common side effect is corneal punctate keratitis. Due to its inhibitory effect on wound healing, MMC should not be used in patients with corneal epithelial defects or shield ulcers. The authors have no experience with this technique and advocate caution with use of topical MMC.

Since no medical treatment has been universally effective at treating vernal keratoconjunctivitis, development of novel therapies continue. Intravenous immunoglobulin infusion, topical probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus drops and oral montelukast sodium, have all been shown effective in treating VKC in small case series.51–53 Further study is needed of these and other new treatment options.

References

1. Duke-Elder, S. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. In: Duke-Elder S, ed. System of ophthalmology, Vol. III, Diseases of the outer eye. London: Henry Kimpton; 1965:476–493.

2. Tuft, SJ, Dart, JK, Kemeny, M. Limbal vernal keratoconjunctivitis: Clinical characteristics and immunoglobulin E expression compared with palpebral vernal. Eye. 1989;3:420–427.

3. Barney, NP. Vernal and atopic keratoconjunctivitis. In: Krachmer JH, Mannis MJ, Holland EJ, eds. Cornea. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:667–670.

4. Kumar, S. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a major review. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:133–147.

5. Leonardi, A, Secchi, AG. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2003;43:41–58.

6. Bonini, S, Coassin, M, Aronni, S, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye. 2004;18:345–351.

7. Cameron, JA. Shield ulcers and plaques of the cornea in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:985–993.

8. Gedik, S, Akova, YA, Gür, S. Secondary bacterial keratitis associated with shield ulcer caused by vernal conjunctivitis. Cornea. 2006;25:974–976.

9. Jeng, BH, Whitcher, JP, Margolis, TP. Pseudogerontoxon. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;32:433–434.

10. Leonardi, A, Busca, F, Motterle, L, et al. Case series of 406 vernal keratoconjunctivitis patients: a demographic and epidemiological study. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:406–410.

11. Bonini, S, Bonini, S, Lambiase, A, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis revisited: a case series of 195 patients with long-term follow-up. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1157–1163.

12. Bonini, S, Lambiase, A, Schiavone, M, et al. Estrogen and progesterone receptors in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1374–1379.

13. Bremond-Gignac, D, Donadieu, J, Leonardi, A, et al. Prevalence of vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a rare disease? Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1097–1102.

14. Totan, Y, Hep en, IF, Cekiç, O, et al. Incidence of keratoconus in subjects with vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a videokeratographic study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:824–827.

en, IF, Cekiç, O, et al. Incidence of keratoconus in subjects with vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a videokeratographic study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:824–827.

15. Cameron, JA, Al-Rajhi, AA, Badr, IA. Corneal ectasia in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1615–1623.

16. Sridhar, MS, Gopinathan, U, Rao, GN. Fungal keratitis associated with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Cornea. 2003;22:80–81.

17. Bonini, S, Bonini, S, Lambiase, A, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a model of 5q cytokine gene cluster disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;107:95–98.

18. Samra, Z, Zavaro, A, Barishak, Y, et al. Vernal keratoconjunctivitis: the significance of immunoglobulin E levels in tears and serum. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1984;74:158–164.

19. Fujishima, H, Saito, I, Takeuchi, T, et al. Immunological characteristics of patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2002;46:244–248.

20. Ableson, MB, Leonardi, AA, Smait, LM, et al. Histaminease activity in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1958–1963.

21. Metz, DP, Hingorani, M, Calder, VL, et al. T-cell cytokines in chronic allergic eye disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:817–824.

22. Leonardi, A, Borghesan, F, Faggian, D, et al. Tear and serum soluable leukocyte activation markers in conjunctival allergic disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:151–158.

23. Abu El-Asarar, AM, Struyf, S, Van Damme, J, et al. Role of chemokines in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2003;43:33–39.

24. Ebihara, N, Funaki, T, Takai, S, et al. Tear chymase in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Curr Eye Res. 2004;28:417–420.

25. Leonardi, A, Brun, P, Di Stefano, A, et al. Matrix metalloproteases in vernal keratoconjunctivitis, nasal polyps and allergic asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:872–879.

26. Leonardi, A, Di Stephano, A, Motterle, L, et al. Transforming growth factor-B/Smad signalling pathway and conjunctival remodeling in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41:52–60.

27. Lambiase, A, Bonini, S, Micera, A, et al. Increased plasma levels of substance P in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:2161–2164.

28. Abu El-Asar, AM, Geboes, K, al-Kharashi, SA, et al. An immunohistochemical study of collagens in trachoma and vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye. 1998;12:1001–1006.

29. Leonardi, A, Abatangelo, G, Cortivo, R, et al. Collagen types I and III in giant papillae of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:482–485.

30. Leonardi, A, Lazzarini, D, Bortolotti, M, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:509–515.

31. Bonini, S, Lambiase, A, Sgrulletta, R, et al. Allergic chronic inflammation of the ocular surface in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;3:381–387.

32. Bonini, S, Pierdomenico, R. Levocabastine eye drops in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1995;5:283–284.

33. Verin, P, Allewaert, R, Joyaux, JC, et al. Comparison of lodoxamide 0.1% ophthalmic solution and levocabastine 0.05% ophthalmic suspension in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2001;11:120–125.

34. Foster, SC. Evaluation of topical cromolyn sodium in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1988;95:194–201.

35. Kazdan, JJ, Crawford, JS, Langer, H, et al. Sodium cromoglycate (intal) in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis and allergic conjunctivitis. Can J Ophthalmol. 1976;11:300–303.

36. Foster, CS, Duncan, J. Randomized clinical trial of topically administered cromolyn sodium for vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1980;90:175–181.

37. Hennawi, M. A double blind placebo controlled group comparative study of ophthalmic sodium cromoglycate and nedocromil sodium in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:365–369.

38. Corum, I, Yeniad, B, Bilgin, LK, et al. Efficiency of olopatadine hydrochloride 0.1% in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis and goblet cell density. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:400–405.

39. D’Angelo, G, Lambiase, A, Cortes, M, et al. Preservative free diclofenac sodium 0.1% for vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2003;241:192–195.

40. Kosrirukvongs, P, Luengchaichawange, C. Topical cyclosporine 0.5 per cent and preservative-free ketorolac tromethamine 0.5 per cent in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. J Med Assoc Thai. 2004;87:190–197.

41. Tabbara, KF, Al-Kharashi, SA. Efficacy of nedocromil 2% versus fluorometholone 0.1%: a randomised, double masked trial comparing the effects on severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:180–184.

42. Sani, JS, Gupta, A, Pandey, SK, et al. Efficacy of supratarsal dexamethasone versus triamcinolone injection in recalcitrant vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:515–518.

43. Holsclaw, DS, Whitcher, JP, Wong, IG, et al. Supratarsal injection of corticosteroid in the treatment of refractory vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am J of Ophthalmol. 1996;121:243–249.

44. Bleik, JH, Tabbara, KF. Topical cyclosporine in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1679–1684.

45. Gupta, V, Sahu, PK. Topical cyclosporine A in the management of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye. 2001;15:39–41.

46. De Smedt, S, Nkurikiye, J, Fonteyne, Y, et al. Topical cyclosporine in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis in Rwanda, Central Africa: a prospective, randomised, double-masked, controlled clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2012;96:323–328.

47. Spadavecchia, L, Fanelli, P, Tesse, R, et al. Efficacy of 1.25% and 1% topical cyclosporine in the treatment of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis in childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2006;17:527–532.

48. Mendicute, J, Aranzasti, C, Eder, F, et al. Topical cyclosporine A 2% in the treatment of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Eye. 1997;11:75–78.

49. Akpek, EK, Hasiripi, H, Christen, WG, et al. A randomized trial of low-dose, topical mitomycin-C in the treatment of severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:263–269.

50. Jain, AK, Sukhija, J. Low dose mitomycin-C in severe vernal keratoconjunctivitis: a randomized prospective double blind study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2006;54:111–116.

51. Derriman, L, Nguyen, DQ, Ramanan, AV, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) in the management of severe refractory vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:667–669.

52. Iovieno, A, Lambiase, A, Sacchetti, M, et al. Preliminary evidence of the efficacy of probiotic eye-drop treatment in patients with vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:435–441.

53. Lambiase, A, Bonini, S, Rasi, G, et al. Montelukast, a leukotriene receptor antagonist, in vernal keratoconjunctivitis associated with asthma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:615–620.