Ventricular Tachycardia in Noncompaction Cardiomyopathy

Pathology of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Incidence of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Clinical Features and Diagnosis of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Subtypes of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Imaging of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Electrocardiography in Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Arrhythmias in Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Clinical Genetics of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

LVNC, characterized by excessive and unusual trabeculation of the mature left ventricle (LV), has been considered to occur because of arrest of the final phase of cardiac development, the compaction phase, where the compact myocardium forms fully. Clinically and pathologically, LVNC is characterized by a spongy morphologic appearance of the myocardium occurring primarily in the LV, with abnormal trabeculations and intertrabecular recesses typically being most evident in the apical portion of the LV.1,2

In 2006, the American Heart Association Scientific Statement on the classification of cardiomyopathies formally classified LVNC as its own disease entity.3 Multiple forms of left ventricular noncompaction occur, including primary myocardial forms of noncompaction, a form associated with electrophysiological abnormalities and arrhythmias, and noncompaction associated with congenital heart disease (CHD) such as septal defects (ventricular or atrial septal defect), pulmonic stenosis, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, among others.4–8 In all forms, metabolic derangements may be notable.5,9 The clinical presentation in some forms of LVNC includes heart failure, thromboembolic events, supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias, and sudden death, and can occur at any age.

Pathology of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

In the early embryo, the heart is a loose interwoven mesh of muscle fibers.10,11 The developing myocardium gradually condenses, and the large spaces within the trabecular meshwork disappear, condensing and compacting the ventricular myocardium and solidifying the endocardial surfaces. Trabecular compaction is normally more complete in the LV than in the right ventricular (RV) myocardium. The situations in which this compacting pathway fails is thought to be due to an arrest in endomyocardial morphogenesis and results in postnatal LV noncompaction.4,10,11 The gross pathologic appearance of LVNC is characterized by numerous, excessively prominent trabeculations and deep intratrabecular recesses resembling RV endomyocardial morphology. Histologically, the recesses and their troughs are lined with endothelium, indicating that these recesses are not sinusoids. In some cases, zones of fibrous and elastic tissue are found scattered on the endocardial surfaces with extension into the recesses. The coronary arterial circulation is usually normal, and extramural myocardial blood supply is not believed to play a role in these abnormalities. Intramural perfusion, however, could be adversely affected by the prominent trabeculations and intratrabecular recesses, particularly the subendocardium. The increased fibrous and elastic tissue on the endocardial surfaces could be due to subendocardial ischemia, perhaps in response to isometric contraction among the trabeculae and recesses. In addition, the endomyocardial morphology of LVNC lends itself to development of mural thrombi within the recesses, which can embolize and cause a stroke.2,8,12,13 Arrhythmias can also occur.14–16

Incidence of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Although LVNC is considered rare by some authors, the incidence and prevalence of LVNC is uncertain.17–20 In the 1990s, the reported prevalence of isolated LVNC was 0.05% of all adult echocardiographic examinations in a large institution, whereas more recently the prevalence was reported as less than 0.14% of all adults referred for echocardiograms. In contrast, Sandhu et al.17 demonstrated a 3.7% prevalence of definite or probable LVNC by echocardiography in adults with LVEF less than or equal to 45% and 0.26% prevalence for all patients referred for echocardiography. Among heart failure patients, the prevalence of LVNC has been reported as 3% to 4%.20 No other reliable data have been reported to date.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

The clinical presentation of LVNC is highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic to end-stage heart failure, lethal arrhythmias, or thromboembolic events.2–7,12–17 LVNC commonly develops in infancy with signs and symptoms of heart failure.2,4,7 Childhood and adult forms are also frequently seen and can occur with heart failure, rhythm abnormalities, or sudden death.12,13,19,20 However, a high percentage of patients are asymptomatic and identified serendipitously on echocardiography, with deep trabeculations and intertrabecular recesses noted in the LV apex and lateral wall. Multiple forms of LVNC exist and the clinical features depend on the specific form of LVNC (discussed later).

In addition to systemic arterial embolism, patients with LVNC are also known to develop ventricular arrhythmias (ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation), atrial fibrillation, or conduction abnormalities (sinus bradycardia, complete heart block). Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is also common.2,7 Reports of survival in children and adults have been inconsistent, with some demonstrating poor outcomes and others having a low percentage of death or transplantation. For example, Ichida et al.7 found good survival and limited symptoms in their childhood patients, whereas Chin et al.4 reported three deaths in the eight children studied. Pignatelli et al.2 demonstrated poor outcomes in neonates but excellent outcomes in those outside the neonatal period. The neonates who died all had systemic disease (mitochondrial and other metabolic disorders); they demonstrated a 5-year survival rate of 86%. When patients receiving transplants were added, the 5-year survival free of death or transplantation was 75%.

Adult clinical studies consistently have described a high risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD) in LVNC,1,13,15 with as many as 47% of adults (and 75% of symptomatic patients) dying within 6 years of presentation. More recent reports, however, have shown a more benign natural history, with lower risk for (malignant) ventricular arrhythmias.21 Bhatia et al.22 reviewed published studies of 241 adults with isolated LVNC diagnosed by echocardiographic criteria followed for a mean duration of 39 months. The annualized event rate was 4% for cardiovascular deaths, 6.2% for cardiovascular death and its surrogates (heart transplantation and appropriate ICD shocks), and 8.6% for all cardiovascular events (death, stroke, ICD shocks, and transplantation). Familial LVNC occurrence was identified in first-degree relatives screened by echocardiography in 30% of index cases.22 The precise substrate for malignant ventricular arrhythmias in LVNC patients is not known,23 and the progression of the disease and evolution of the arrhythmic substrate remains speculative. Histologic examination shows myocardium around deep intratrabecular recesses that can serve as slow conducting zones with reentry. Furthermore, impaired flow reserve, causing intermittent ischemia, has been proposed as having a role24; however, inducibility of sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT) during electrophysiological studies has demonstrated little value as a tool for risk stratification in LVNC.14,23

Subtypes of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

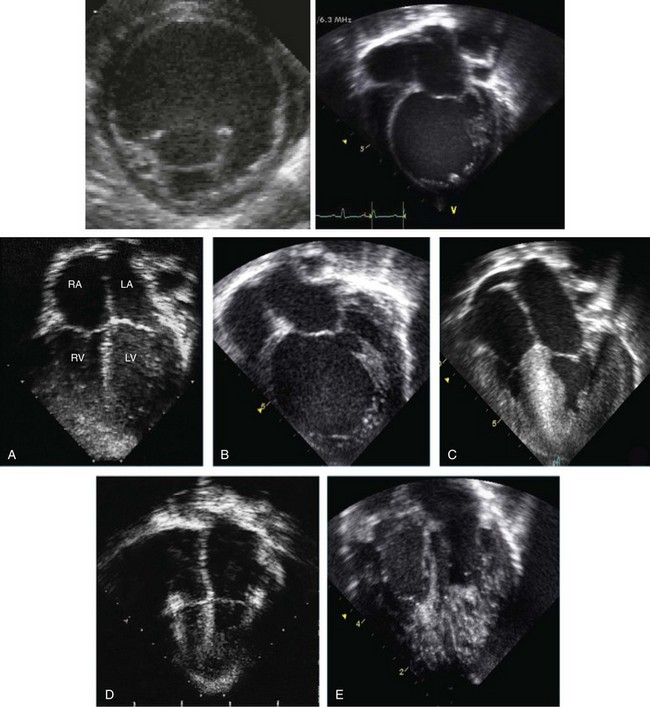

Although an increasing number of clinicians are beginning to recognize the clinical features of LVNC, several key points have failed to be described. One of the important issues in the diagnosis and outcomes of these patients, particularly in childhood, is the specific LVNC phenotype that exists in any one subject. There are at least seven different phenotypes of LVNC and these different phenotypes have different outcomes (Figure 90-1). The subtypes include the following types:

Figure 90-1 Echocardiographic pictorial of heterogeneous forms of left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC). The top panel shows a parasternal short axis view of a dilated form of LVNC. The apical trabeculations are noted at the apex. An apical four-chamber view at the right side of the figure demonstrates the same findings. The lower panel shows heterogeneous phenotypes associated with LVNC. A, LVNC with normal LV size, thickness, and function. B, Dilated form of LVNC. C, Hypertrophic form of LVNC. D, Restrictive form of LVNC. E, Biventricular LVNC.

1. Isolated LVNC, in which abnormal trabeculations are associated with normal LV size, thickness, and systolic and diastolic function in the absence of other structural heart disease with no evidence of arrhythmias. Clinically, this subgroup appears to be benign during childhood and approximates 25% of all subjects. These individuals do well unless they exhibit ventricular arrhythmias. This subgroup is usually followed up yearly in the outpatient clinic, and patients are not treated with medication and or restricted from activities.4,6,7,25

2. In isolated LVNC with arrhythmias, there is normal LV size, thickness, and function on imaging, but there are predominant arrhythmias, usually runs of tachyarrhythmias. These patients appear to have an elevated risk of sudden events and require closer follow-up and therapeutic intervention with either medication or implantable defibrillator, depending on the specific arrhythmia and associated symptoms. The arrhythmias noted include VT, ventricular fibrillation (VF), atrioventricular block, supraventricular tachycardia, and atrial fibrillation.26,27 Preexcitation and extreme voltages are also common electrocardiogram (ECG) findings, particularly in children.2

3. The dilated form of LVNC clinically mimics dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM), with a dilated trabeculated LV with depressed systolic function, and likely has similar outcomes. The follow-up for these patients is similar to those with pure DCM. An important differentiating feature is the potential for this to become an “undulating phenotype” in which the heart changes its appearance to a hypertrophic form or one with normal LV size, thickness, and function on echocardiography, but later reverts to the DCM-like phenotype.2 The ECGs of these patients, particularly the young children, can include preexcitation with or without severe increase in voltage, particularly in the mid-precordium, and arrhythmias.2

4. The hypertrophic form of LVNC mimics hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) with LV hypertrophy (commonly with asymmetrical septal hypertrophy) and a small, trabeculated LV cavity. Hypercontractile systolic function and diastolic dysfunction and appear to have similar outcomes. The follow-up for these patients is similar to those with pure HCM. An important differentiating feature is the potential for this to become an undulating phenotype in which the heart changes its appearance to a dilated form or a dilated and hypertrophic form with depressed systolic function, but later reverts to the HCM-like phenotype.2 The ECGs of these patients have the same abnormalities as the other forms.2

5. The hypertrophic and dilated form of LVNC appears to be the worst form of LVNC clinically and, in many cases, is associated with neuromuscular disease and hypotonia. These young children, particularly infants, can succumb to heart failure or arrhythmias, especially if they have metabolic derangement.2,9 The ECGs of these patients have the same abnormalities as the other forms. An important differentiating feature is the potential for this to become an undulating phenotype in which the heart changes its appearance to a dilated or hypertrophic form on echocardiography, but later reverts to the HCM-dilated phenotype.2

6. The restrictive form of LVNC is a rare form of LVNC and is clinically challenging because it mimics the clinical behavior of restrictive cardiomyopathy, with dilated atria and diastolic dysfunction associated with a trabeculated LV with normal dimension, thickness, and systolic function.28 Like the children with restrictive cardiomyopathy, this subgroup typically is considered a transplant candidate early after diagnosis.

7. In LVNC with congenital heart disease, any form of CHD can occur in conjunction with LVNC, but right heart obstructive forms are most typical. 18 The most common simple forms of CHD include septal defects and pulmonic stenosis. However, LVNC has been identified in subjects with severe forms of CHD, including Ebstein anomaly, pulmonary atresia, tricuspid atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and heterotaxy syndrome. Outcomes depend on the specific CHD but can be worse than the postoperative outcomes of the same CHD without LVNC. In this case, the surgeon, cardiac anesthesiologist, and cardiac intensivist must play close attention to the myocardial function and treat it expectantly.

Imaging of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Echocardiography has been the most commonly used modality to diagnose and describe LVNC. Recently, Punn and Silverman29 investigated LVNC using the 16-segment model described by the American Heart Association and the American Society of Echocardiography. Using the ratio of noncompaction to compaction, the authors analyzed the 16 segments to determine whether severity was correlated with poor outcomes in these affected children. Forty-four patients with LVNC were studied, consistent with an incidence of 0.3% of admissions. Twenty-eight patients (64%) remained alive (group 1), and 16 patients (36%) either died or were received a transplant (group 2). This latter group had a substantial number of patients with significant associated CHD compared with the group that survived (50% vs. 18%; P < .05). Similar regions of involvement in the 16-segment model were notable, with sparing of basal segments and involvement of the midpapillary and apical regions (P < .001); however, patients in group 2 (high percentage of death and transplant) had more segments involved (six vs. four; P < .05), lower shortening fractions (16% vs. 29%; P < .001), and lower ejection fractions (24% vs. 47%; P < .001), with the ejection fraction inversely related to the number of segments (r = −0.63; P < .01), suggesting that more noncompaction portends a worse outcome. In the younger patients with noncompaction, poor outcomes were related to the number of LV segments involved.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) is another imaging modality that has been used increasingly to evaluate and diagnose LVNC. Thuny et al.30 compared two-dimensional echocardiography images obtained at end-diastole and end-systole against CMR images obtained at end-diastole to validate the diagnosis of LVNC. Sixteen adults (48 ± 17 years) with LVNC underwent echocardiography and CMR within the same week and were compared to assess noncompaction in 17 anatomic segments. All segments were analyzed using CMR, but only 87% could be analyzed with echocardiography. A two-layered structure was observed in 54% of patients by CMR, 43% by echocardiography. Echocardiography underestimated the noncompact-to-compact maximal ratio compared with CMR. Therefore, CMR was thought to be superior to standard echocardiography in assessing the extent of noncompaction and provide supplemental morphologic information beyond that obtained with conventional echocardiography; however, this has not been validated in children.

Electrocardiography in Left Ventricular Noncompaction

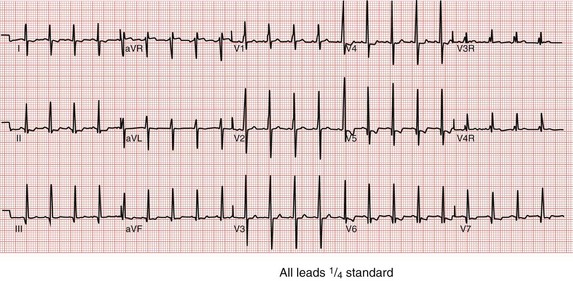

The ECG for patients with LVNC is typically abnormal and, in infants and young children, commonly shows excessive voltage (Figure 90-2).2,7 In fact, approximately 30% of these young subjects with LVNC have extreme midprecordial voltages that mimic the ECG seen in Pompe disease. These subjects, particularly those with the childhood forms of LVNC, may be associated with preexcitation as well. Arrhythmias, including supraventricular tachycardia, VT, and atrial fibrillation, are common and dangerous accompaniments to all subtypes of LVNC.

Arrhythmias in Left Ventricular Noncompaction

As noted, both supraventricular and ventricular rhythm disorders are frequently observed in patients with LVNC. Most importantly, these patients are prone to developing life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias, which are among the most frequent causes of death in subjects with LVNC. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) have been demonstrated to be highly effective for the prevention of sudden arrhythmic death in patients with LVNC and should be considered in patients who are judged clinically to be at high risk for ventricular tachyarrhythmias. These patients include those with a severely reduced ejection fraction and those with a history of sustained VT or VF, recurrent syncope of unknown etiology, or a family history of ventricular tachyarrhythmias or sudden cardiac death. Ventricular tachyarrhythmias, including cardiac arrest owing to VF, are reported in 38% to 47% and sudden death in 13% to 18% of adult patients with LVNC.15,16,23,27 Caliskan et al.31 recently investigated ICD therapy indications and outcomes in 77 patients with LVNC (mean age, 40 ± 14 years), 44 (57%) of whom had an ICD implanted using standard ICD guidelines for nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Implantation for secondary prevention occurred in 12 patients (7 with VF, 5 with sustained VT) and for primary prevention (heart failure or severe LV dysfunction) in 32 patients.31 During a mean follow-up of 33 ± 24 months, eight patients presented with appropriate ICD shocks owing to sustained VT after a median 6.1 (range, 1 to 16) months, including 4 of 32 (13%) patients in the primary prevention group and 4 of 12 (33%) in the secondary prevention group (P = .04). An additional nine patients had received inappropriate ICD therapy: six (19%) in the primary group and three (25%) in the secondary prevention group, at a median follow-up of 4 months (range, 2 to 23 months). The relatively high percentage of appropriate shocks for sustained VT in this population suggests that patients with LVNC are at high risk for SCD and that implanting an ICD in these adult patients is appropriate, although no patients with LVNC were included in previous trials that are the basis of the current guidelines.32 All the appropriate ICD interventions in this patient cohort were due to fast VTs, although it is not certain that the initial rhythm in those SCD and VF patients was also started with a VT trigger.33 In these patients with LVNC and sustained VT or VF, there was a 33% risk of recurrent, sustained VT followed by appropriate ICD shocks after a median follow-up period of 26 months. Similarly, Kobza et al.34 reported 37% appropriate shocks during a mean follow-up of 40 months among 30 patients with LVNC and an ICD. These observations support the current guidelines to implant an ICD for primary prevention, based on the presence of heart failure or severe LV dysfunction in combination with other (presumed) high-risk factors in patients with LVNC.

In the cohort reported by Caliskan et al.,31 severe LV dysfunction or dilation were not prominent in the secondary prevention group with a history of sustained VT or VF, making it difficult to rely on the severity of the LV dysfunction for SCD risk stratification.31 There were more PVCs in the patients treated with an ICD than in those without one, with a trend toward higher numbers of PVCs in the secondary prevention group with VT or VF, versus those receiving an ICD for primary prevention. Nonsustained VT was also more frequent on 24-hour Holter recording in the VT/VF group versus both the primary prevention patients and to those without ICD. Other potential risk factors for SCD in LVNC patients, like a positive family history, syncope, or inducible VT/VF, must also be considered, similar to that seen in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.35 In this context, it is worth mentioning that sarcomeric gene mutations were reported in the LVNC population, implying that LVNC is part of a broader spectrum of cardiomyopathies including hypertrophic, restrictive, and dilated cardiomyopathy.36

Clinical Genetics of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Left ventricular noncompaction most commonly has X-linked recessive or autosomal dominant inheritance.25,37 In X-linked LVNC, female carriers have not been found to develop frank clinical disease and are echocardiographically normal. Consistent with X-linked inheritance, no male-to-male transmission of the disease occurs. Autosomal dominant inheritance occurs in some familial cases of LVNC without CHD and in most, if not all, cases associated with CHD.7,21,25,36 Autosomal recessive and mitochondrial inheritance is seen in cases dominated by mitochondrial and metabolic derangement.9,25 When LVNC is associated with CHD, the congenital cardiac defect can be heterogeneous in families, but is transmitted as an autosomal dominant trait along with the myocardial abnormality. In some families with autosomal dominant LVNC associated with CHD, affected members can be identified in whom no CHD can be identified at the time of evaluation, because the cardiac defects include minor forms of CHD, such as small atrial or ventral septal defects or patent ductus arteriosus, which have spontaneously closed, along with other individuals with severe CHD, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Penetrance is reduced in some families. Ichida et al.7 reported that 44% of LVNC patients had inherited LVNC, with 70% having autosomal dominant and 30% having X-linked inheritance.

Molecular Genetics of Left Ventricular Noncompaction

Mutations in the G4.5 or tafazzin (TAZ) gene were among the first to be identified in male patients and carrier females with isolated LVNC and with Barth syndrome. This gene encodes a novel protein family (tafazzins) that participate in the metabolism of cardiolipin, the signature phospholipid of mitochondria, and is also responsible for Barth syndrome and other forms of infantile cardiomyopathies.25,37 Barth syndrome is a clinical association of myocardial dysfunction, neutropenia, skeletal myopathy, abnormal mitochondria, organic aciduria (primarily 3-methylglutaconic aciduria), growth retardation, and cholesterol abnormalities.37 It is an X-linked disorder and has been thought to be allelic to several phenotypically different disorders on Xq28,25,37such as LVNC and dilated cardiomyopathy. Congenital heart defects have not been associated with Barth syndrome or other G4.5/TAZ-associated disease. The genetic basis of autosomal dominant LVNC has also been studied, and multiple genes have been identified. Ichida et al.8 identified mutations in α-dystrobrevin as causative in children and young adults with LVNC with or without congenital heart disease. Subsequently, mutations in sarcomere protein- and Z-line protein-encoding genes were identified, with mutations in β-myosin heavy chain (MYH7), α-cardiac actin (ACTC), cardiac troponin T (TNNT2), and ZASP.25,36,38,39 In addition to sarcomere-encoding genes and the cytoskeleton, mutations in the sodium channel gene SCN5A have been shown to cause LVNC and rhythm disturbance.40 Another cytoskeletal protein that has been associated with LVNC is dystrophin in boys with Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophy.41 Skeletal muscle biopsy has, in some patients, identified mitochondrial abnormalities, suggesting a nuclear import protein as the primary abnormality. Mutation analysis of the mitochondrial genome has identified mutations as well.42 Consideration of other potential genetic causes needs to account for the known molecular defects resulting in congenital heart anomalies, as well as those molecular abnormalities resulting in diseases of the myocardium itself.

Therapy and Outcome

In patients having associated congenital heart disease, appropriate therapeutic approaches can include simple pharmacologic therapy with diuretics for volume overload associated with left to right shunts, more complex pharmacologic therapy for patients with restrictive physiology and pulmonary hypertension, or invasive therapy with catheter intervention or surgical repairs, depending on the lesions. Intimate understanding of the cardiac function abnormalities, evidence of thrombi (which should be treated with anticoagulation), and the metabolic status of the patient must be addressed by the interventional cardiologist, cardiac anesthesiologist, and surgeon in approaching these patients invasively. In addition, cardiac rhythm disturbances need to be identified and therapies such as pacemakers, ICDs, and intracardiac ablations should be considered. Finally, in patients with heart failure associated with any form of LVNC, mechanical circulatory support and transplantation may be necessary.43

References

1. Engberding, R, Yelbuz, TM, Breithardt, G. Isolated noncompaction of the left ventricular myocardium: a review of the literature two decades after the initial case description. Clin Res Cardiol. 2007; 96:481–488.

2. Pignatelli, RH, McMahon, CJ, Dreyer, WJ, et al. Clinical characterization of left ventricular noncompaction in children. A relatively common form of cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2003; 108:2672–2678.

3. Maron, BJ, Towbin, JA, Thiene, G, et al. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: an American Heart Association Scientific Statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Heart Failure and Transplantation Committee; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Groups; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2006; 113:1807–1816.

4. Chin, TK, Perloff, JK, Williams, RG, et al. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation. 1990; 82:507–513.

5. Finsterer, J, Stöllberger, C, Fazio, G. Neuromuscular disorders in left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. Curr Pharm Des. 2010; 16(26):2895–2904.

6. Oechslin, E, Jenni, R. Left ventricular non-compaction revisited: a distinct phenotype with genetic heterogeneity? Eur Heart J. 2011; 32(12):1446–1456.

7. Ichida, F, Hamamichi, Y, Miyawaki, T, et al. Clinical features of isolated noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium: Long-term clinical course, hemodynamic properties and genetic background. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999; 34:233–240.

8. Ichida, F, Tsubata, S, Bowles, KR, et al. Novel gene mutations in patients with left ventricular noncompaction or Barth syndrome. Circulation. 2001; 103:1256–1263.

9. Scaglia, F, Towbin, JA, Craigen, WJ, et al. Clinical spectrum, morbidity, and mortality in 113 pediatric patients with mitochondrial disease. Pediatrics. 2004; 114:925–931.

10. Sedmera, D, McQuinn, T. Embryogenesis of the heart muscle. Heart Fail Clin. 2008; 4:235–238.

11. Risebro, CA, Riley, PR. Formation of the ventricles. Scientif World J. 2006; 6:1862–1880.

12. Stöllberger, C, Blazek, G, Dobias, C, et al. Frequency of stroke and embolism in left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. Am J Cardiol. 2011; 108(7):1021–1023.

13. Greutmann, M, Mah, ML, Silversides, CK, et al. Predictors of adverse outcome in adolescents and adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 109(2):276–281.

14. Steffel, J, Kobza, R, Oechslin, E, et al. Electrocardiographic characteristics at initial diagnosis in patients with isolated left ventricular noncompaction. Am J Cardiol. 2009; 104:984–989.

15. Caliskan, K, Ujvari, B, Bauernfeind, T, et al. The prevalence of early repolarization in patients with noncompaction cardiomyopathy presenting with malignant ventricular arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012; 23(9):938–944.

16. Celiker, A, Ozkutlu, S, Dilber, E, et al. Rhythm abnormalities in children with isolated ventricular noncompaction. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005; 28(11):1198–1202.

17. Sandhu, R, Finkelhor, RS, Gunawardena, DR, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of left ventricular noncompaction in a community hospital cohort of patients with systolic dysfunction. Echocardiography. 2008; 25(1):8–12.

18. Hughes, ML, Carstensen, B, Wilkinson, JL, et al. Angiographic diagnosis, prevalence and outcomes for left ventricular noncompaction in children with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young. 2007; 17(1):56–63.

19. Aras, D, Tufekcioglu, O, Ergun, K, et al. Clinical features of isolated ventricular noncompaction in adults long-term clinical course, echocardiographic properties, and predictors of left ventricular failure. J Card Fail. 2006; 12:726–733.

20. Kovacevic-Preradovic, T, Jenni, R, Oechslin, EN, et al. Isolated left ventricular noncompaction as a cause for heart failure and heart transplantation: a single center experience. Cardiology. 2009; 112:158–164.

21. Murphy, RT, Thaman, R, Blanes, JG, et al. Natural history and familial characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction. Eur Heart J. 2005; 26:187–192.

22. Bhatia, NL, Tajik, AJ, Wilansky, S, et al. Isolated noncompaction of the left ventricular myocardium in adults: a systematic overview. J Card Fail. 2011; 17(9):771–778.

23. Caliskan, K, Kardos, A, Szili-Torok, T. Empty handed: A call for an international registry of risk stratification to reduce the “sudden-ness” of death in patients with non-compaction cardiomyopathy. Europace. 2009; 11:1138–1139.

24. Fazio, G, Novo, G, Casalicchio, C, et al. Left ventricular non-compaction cardiomyopathy in children: Is segmental fibrosis the cause of tissue Doppler alterations and of EF reduction? Int J Cardiol. 2009; 132(2):278–280.

25. Towbin, JA. Left ventricular noncompaction: a new form of heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2010; 6(4):453–469.

26. Stöllberger, C, Blazek, G, Wegner, C, et al. Heart failure, atrial fibrillation and neuromuscular disorders influence mortality in left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. Cardiology. 2011; 119(3):176–182.

27. Steffel, J, Duru, F. Rhythm disorders in isolated left ventricular noncompaction. Ann Med. 2012; 44(2):101–108.

28. Martinez, HR, Niu, MC, Sutton, VR, et al. Coffin-Lowry syndrome and left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy with a restrictive pattern. Am J Med Genet A. 2011; 155A(12):3030–3034.

29. Punn, R, Silverman, NH. Cardiac segmental analysis in left ventricular noncompaction: experience in a pediatric population. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010; 23(1):46–53.

30. Thuny, F, Jacquier, A, Jop, B, et al. Assessment of left ventricular non-compaction in adults: side-by-side comparison of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with echocardiography. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2010; 103(3):150–159.

31. Caliskan, K, Szili-Torok, T, Theuns, DA, et al. Indications and outcome of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary and secondary prophylaxis in patients with noncompaction cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011; 22(8):898–904.

32. Narang, R, Cleland, JG, Erhardt, L, et al. Mode of death in chronic heart failure. A request and proposition for more accurate classification. Eur Heart J. 1996; 17:1390–1403.

33. Zipes, DP, Camm, AJ, Borggrefe, M, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop Guidelines for Management of Patients with Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death): Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2006; 114:e385–e484.

34. Kobza, R, Steffel, J, Erne, P, et al. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator and cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with left ventricular noncompaction. Heart Rhythm. 2010; 7(11):1545–1549.

35. Autore, C, Quarta, G, Spirito, P. Risk stratification and prevention of sudden death in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2007; 9(6):431–435.

36. Hoedemaekers, YM, Caliskan, K, Majoor-Krakauer, D, et al. Cardiac beta-myosin heavy chain defects in two families with non-compaction cardiomyopathy: Linking non-compaction to hypertrophic, restrictive, and dilated cardiomyopathies. Eur Heart J. 2007; 28:2732–2737.

37. Aprikyan, AA, Khuchua, Z. Advances in the understanding of Barth syndrome. Br J Haematol. 2013; 161(3):330–338.

38. Teekakirikul, P, Kelly, MA, Rehm, HL, et al. Inherited cardiomyopathies: molecular genetics and clinical genetic testing in the postgenomic era. J Mol Diagn. 2013; 15(2):158–170.

39. Klaassen, S, Probst, S, Oechslin, E, et al. Mutations in sarcomere protein genes in left ventricular noncompaction. Circulation. 2008; 117(22):2893–2901.

40. Shan, L, Makita, N, Xing, Y, et al. SCN5A variants in Japanese patients with left ventricular noncompaction and arrhythmia. Mol Genet Metab. 2008; 93(4):468–474.

41. Finsterer, J, Stöllberger, C. Primary myopathies and the heart. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2008; 42(1):9–24.

42. Tang, S, Batra, A, Zhang, Y, et al. Left ventricular noncompaction is associated with mutations in the mitochondrial genome. Mitochondrion. 2010; 10(4):350–357.

43. Hanke, SP, Gardner, AB, Lombardi, JP, et al. Left ventricular noncompaction cardiomyopathy in barth syndrome: an example of an undulating cardiac phenotype necessitating mechanical circulatory support as a bridge to transplantation. Pediatr Cardiol. 2012; 33(8):1430–1434.