187 Venous ulcer

Salient features

History

• Varicose veins; ask about duration

• Past history of venous thromboembolism

• Duration of ulceration and whether this is the first episode or recurrent

• Pain (lack of pain suggests neuropathic aetiology)

• Rheumatoid arthritis (remember up to half the patients with rheumatoid arthritis have venous leg ulcers rather than the result of rheumatoid arthritis).

Examination

• Ulcer located on the medial aspect of leg (around the ankles) with pigmentation

• Surrounding dermatitis and excoriation from pruritus (stasis dermatitis)

• White atrophy with scars in the overlying skin

• The ulcer may be secondarily infected (cellulitis or thrombophlebitis)

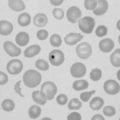

• Look for varicose veins (Fig. 187.1)

• The range of hip, knee and ankle movement should be determined

• Sensation should be tested with a monofilament to exclude peripheral neuropathy (neuropathic arthritis or Charcot’s joints, see p. 496).

Advanced-level questions

What causes the surrounding pigmentation?

It results from extravasation of red blood cells and haemosiderin deposition.

What causes the white atrophy (atrophie blanche)?

It results from hyalization of skin vessels, leading to scars in the overlying skin.

How would you manage such an ulcer?

• Reduction of venous hypertension and oedema. Elevation of the limbs, wearing support bandages, weight reduction in the obese. The mainstay of community management of venous ulcers is graduated compression bandaging (in these patients the ankle brachial pressure index must be at least 0.8). The healing rate depends on the initial size of the ulcer, but 65–70% of venous ulcers heal within 6 months

• Control surrounding inflammation. Wet compresses, topical steroids

• Infection: antibiotics for cellulitis

• Dermatitis: zinc and salicylic acid paste

• Skin on the lower leg must be kept moist: emollient such as simple aqueous cream or 50:50 liquid paraffin

• Ulcers: cleaning with potassium permanganate, debridement, skin grafting

• Treatment of varicose veins. Long saphenous or short saphenous incompetence in the presence of normal deep veins may benefit from surgery to correct venous abnormality in the leg and allow ulcer healing. Patients with refluxing deep veins would benefit from compression bandaging.

What are the factors that influence venous pressure in the legs?

Pressure in the veins of the leg is determined by three components.

• Hydrostatic component related to the weight of the column of blood from the right atrium to the foot (during standing without skeletal muscle activity, venous pressures in the legs are determined by the hydrostatic component and capillary flow, and they may reach 80–90 mmHg)

• Hydrodynamic component related to pressures generated by contractions of the skeletal muscles of the leg and the pressure in the capillary network (skeletal muscle contractions, as during ambulation, transiently increase pressure within the deep leg veins)

• Venous valve component, if effective, ensures that venous blood flows toward the heart, thereby emptying the deep and superficial venous systems and reducing venous pressure, usually to <30 mmHg. Both hydrostatic and hydrodynamic effects are profoundly influenced by the action of the venous valves. Even very small leg movements can provide important pumping action. In the absence of competent valves, the decrease in venous pressure with leg movements is attenuated. If valves in the perforator veins are incompetent, the high pressures generated in the deep veins by calf muscle contraction can be transmitted to the superficial system and to the microcirculation in skin.