CHAPTER 14 Venoactive Drugs

Introduction

Venoactive drugs (VAD) are a heterogeneous group of medicinal products, of plant or synthetic origin, which have effects on edema (C3) and on symptoms related to chronic venous disease (CVD, classes C0s–C6s according to the CEAP classification).1,2 A specific ‘pain-killer’ effect has been suggested, as VAD are active on venous pain, which does not respond to anti-inflammatory drugs.1–5

The main mechanisms of action of VAD are:

Effectiveness of VAD has been regularly discussed, mostly by pharmacologists. Some of them have a poor knowledge of phlebology and VAD; their assertions are debatable. Others are not aware of the difficulty of assessing the activity of VAD.13 Symptoms are subjective, although they can be correctly quantified. Clinical signs such as edema are not easy to measure, owing to significant daily variations in each individual. Efficacy of VAD on edema and venous symptoms may currently be considered as correctly established. However, there is a need for further randomized, controlled clinical trials with greater attention paid to methodological quality.13–15

Classification of VAD

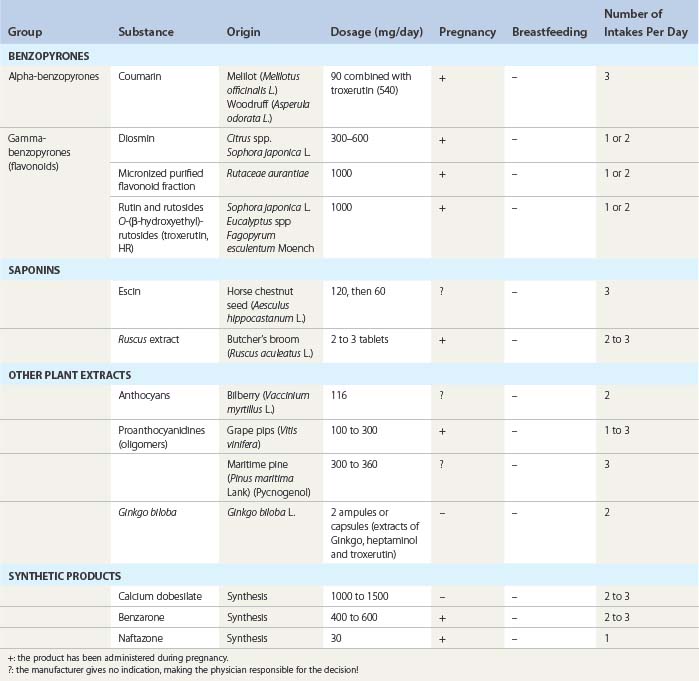

The various classes of VAD are shown in Table 14.1.1–3

In this chapter, we shall distinguish VDA as:

Benzopyrones

This large group of medicines contains many substances, which are often closely related and endowed with multiple pharmacologic properties. Benzopyrones (alpha-pyrones and gamma-pyrones) are obtained from many indigenous and exotic plants, often used in traditional medicine. They belong to the family of phytophenols, and are related to resveratrol, which is currently undergoing a wide range of studies to assess its possible preventative and therapeutic value in atherosclerosis.16

Alpha-benzopyrones

Coumarin induces proteolysis of high-molecular-weight proteins present in lymphedema. Small-size protein fragments can then be more easily drained via the lymphatics. The oncotic pressure drops and edema lessens. However, effectiveness is debatable.17 Although coumarin and its derivatives have an antiedematous effect, they do not modify the coagulation of blood, in contrast to dicoumarols. Alongside its therapeutic properties, the aromatic properties of coumarin are extensively used in spices for cooking, cosmetology (soap, perfumes) and the tobacco industry.

Several cases of drug-related hepatitis have been reported after taking high doses of coumarin or dicoumarols as an anticoagulant. Coumarin has been withdrawn from the market for this reason, except in brands associating low doses of coumarin and troxerutin.18

Gamma-benzopyrones (flavonoids)

Substances mostly used therapeutically in CVD are described below.

Diosmin and Micronized Purified Flavonoid Fraction

Diosmin (3′,5,7-trihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavone-7-rhamnoglucoside) is extracted from plants (rutaceae) or obtained by synthesis (as another bioflavonoid, hidrosmin).19 The half-life of diosmin is 8 to 12 hours, with its elimination being renal (65%) and biliary (35%).

Micronization enables a decrease in particle size of the flavone fraction from 20 to 2 µM (MPFF20–45), thereby increasing the intestinal absorption and bioavailability of the substance, as has been demonstrated in two clinical trials.22–27

MPFF is indicated in the treatment of edema and of symptoms related to venous insufficiency (edema, heavy legs, discomfort, pruritus, night cramps, pain, swelling), pelvic congestion syndrome,42 venous surgery (decrease in postoperative pain and more rapid recovery43,44) as well as lymphedema, including filarial.45 Its other indications are gynecological (tense painful breasts, IUD-related bleeding) and proctological.

All of these effects have been confirmed in double-blind clinical trials,20–44 which also showed a significant improvement in the quality of life of patients suffering from (chronic venous insufficiency) CVI. According to five clinical trials joined in a meta-analysis, MPFF may hasten the healing of leg ulcers.41

Rutosides and Oxerutin

A standard mixture of several flavonoid derivatives is obtained by hydroxyethylation of a natural substance, rutin. Troxerutin is a fraction of oxerutine. Absorbed by the digestive tract, oxerutine has a half-life of 24 hours and is principally excreted in bile. A large number of pharmacological and clinical studies46–58 have provided evidence of its influence on disturbances of capillary permeability, effects on erythrocyte deformation and aggregation, antiedematous actions, and inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis. Its diffusion and accumulation in the venous wall have been demonstrated.54

Saponins

Escin

Escin increases venous wall tone and has a well-demonstrated antiedematous effect.59–64 The HSCE extracts have been evaluated in one Cochrane study, curiously excluding other VADs.12

Ruscus

Extracts of ruscus (butcher’s broom) contain saponins and flavonoids. The precise composition of these extracts is poorly understood. Venotonic and antiedematous actions have been well demonstrated in open and randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies and are associated with a reduction of symptoms in patients suffering from CVD.65–74

Other plant extracts

Extracts of Ginkgo biloba75–78 contain terpens and flavonoids. Antagonists of platelet activating factor (PAF), they have an action on platelet aggregation, blood viscosity, and edema. Extracts of Centella asiatica79,80 are believed to enhance collagen synthesis in connective tissue.

Many other plants are used in the treatment of symptoms of CVD. All of them contain flavonoids among other active substances: procyanidolic oligomers (anthocyans in bilberry extracts; proanthocyanidols in white grape pit, Vitis vinifera,81,82 maritime pine (Pycnogenol)83–85).

Synthetic drugs

Calcium dobesilate

Calcium dobesilate decreases capillary permeability and blood viscosity, and improves lymphatic drainage.86–96 The antiedematous effect persists for about 2 months after treatment is stopped.

Benzarone

Several cases of severe hepatitis have been reported.97 Photosensitization may occur during treatment.

Naftazone

Beta-naphtoquinone monosemicarbazone or naftazone98,99 is rapidly absorbed from the digestive tract. Its half-life is short (1.5 hours) and its metabolites are eliminated in urine.

Principal Mode of Action of VAD

Administration, Dosage, Limits

Usual dosages are mentioned in Table 14.1. Low VAD doses should not be prescribed, as they are ineffective.1,2 Combinations of different preparations, whose value has not been validated by clinical trials, is to be avoided.2

Duration of treatment

A course of VAD treatment generally lasts 1 month. It is not appropriate to prescribe a VAD for more than 3 months except in the event of re-emergence of the symptoms after treatment discontinuation.2

Premenstrual syndrome

A particular dosage regimen (intake restricted to the last 2 weeks of the menstrual cycle) has been recommended for women presenting with premenstrual syndrome with pain and edema of the legs.100–102

Pregnancy and lactation

Some VAD have been used without any problems during the second and third trimester of pregnancy to relieve edema and symptoms of CVD and have been effective.103–105 They are indicated in Table 14.1. The pharmaceutical companies do not advise administration during pregnancy, however, and generally recommend that VAD should not be administered during breastfeeding.

Topical application

Topical VAD preparations are also available (rutosides, diosmin, escin, calcium dobesilate, among others). Absorption of the active drug has been demonstrated to have a degree of efficacy in a few double-blind studies.106,107

Scientifically Recognized Indications

Main indications of VAD

Leg ulcer

Double-blind studies using MPFF29,40 and one meta-analysis41 have demonstrated an adjuvant effect on healing of leg ulcers when larger than 5 cm2 and existing for more than 6 months. Pain was relieved in all treated patients.

Long-term administration of rutosides did not prevent leg ulcer relapses in one study.46

Results

The evaluation of VAD is complex since:

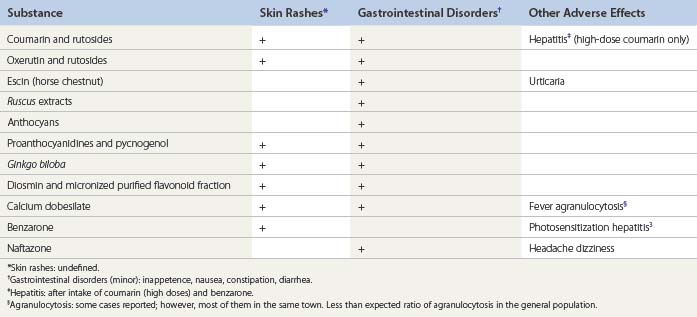

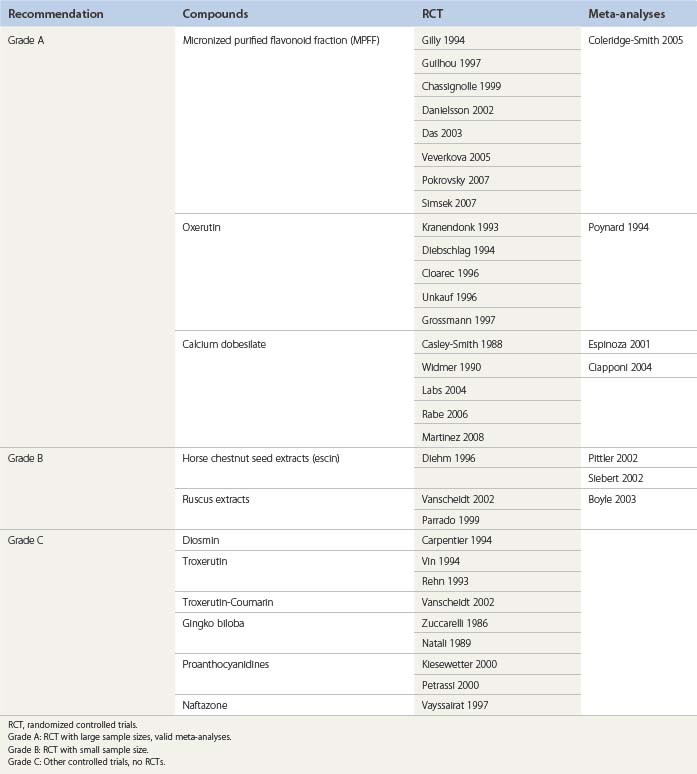

Demonstrated therapeutic effect

More than 130 RCTs or meta-analyses have been published to validate the clinical effectiveness of VAD.17–107 These publications have been evaluated in Cochrane reviews,13,64 in other reviews,15 and in consensus meetings, as in Paphos4 and Siena.3

Recommendations according to three levels of evidence – A, B, and C – may be suggested after a critical review of the different papers devoted to VAD (Table 14.3):

Guidelines

Scientific societies have published guidelines with the purpose of developing double-blind trials whose parameters are incontestable.14

The American Venous Forum in its Guidelines suggests the use of VAD (as MPFF and rutosides) in hot climates when the wearing of stockings is less acceptable. MPFF might be a useful adjunct to conventional therapy in large and long-standing ulcers which might otherwise be expected to heal slowly.108

In patients with persistent venous ulcers, the American College of Chest Physicians suggest that MPFF administered orally be added to local care and compression.109

Conclusions

Successful treatment of venous symptoms is cost-effective. Renouncement of the use of VAD may induce an augmentation of health budget in the mid term, as demonstrated by Allegra.110 If patients do not present early for symptoms of CVD, the complications from venous disorders will surmount, inducing higher expenses: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be prescribed for venous pain, with expensive side effects; days off work may increase, among other effects of insufficient and late treatment of CVD, including alteration to quality of life.

1 Ramelet AA, Perrin M, Kern P. Bounameaux H. Phlebology, 5th ed. Paris: Elsevier; 2008.

2 Ramelet AA, Kern P, Perrin M. Varicose veins and telangiectasias. Paris: Elsevier; 2004.

3 Ramelet AA, Boisseau MR, Allegra C, et al. Veno-active drugs in the management of chronic venous disease. An international consensus statement: current medical position, prospective views and final resolution. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2005;33:309.

4 Nicolaides AN, Allegra C, Bergan J, et al. Management of chronic venous disorders of the lower limbs – guidelines according to scientific evidence. International Angiology. 2008;27:1.

5 Gobin JP, Ramelet AA. Place actuelle des médicaments veino-actifs dans le traitement des affections veineuses chroniques. Phlébologie. 2008;61:395.

6 Ramelet AA. Management of chronic venous disease: the example of Daflon 500 mg. Phlebolymphology. 2009. in press

7 Diem C. The role of oedema protective drugs in the treatment of CVI: a review of evidence based and placebo-controlled clinical trials with regard to efficacy and tolerance. Phlebology. 1996;11:23.

8 Kurtz X. Chronic venous insufficiency of the leg: epidemiology, outcomes, diagnosis and management. Summary of an evidence-based report of the VEINES task force. Int Angiol. 1999;18:83.

9 Boada JN, Nazco GJ. Therapeutic effect of venotonics in chronic venous insufficiency: a meta-analysis. Clin Drug Invest. 1999;18:413.

10 Clement DL. Management of venous edema: insights for an international task force. Angiology. 2000;51:13.

11 Frick RW. Three treatments for chronic venous insufficiency: escin, hydroxyethylrutoside and Daflon. Angiology. 2000;51:197.

12 Pittler MH, Ernst E. Horse chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Jan 2006;25(1):CD003230.

13 Martinez MJ, Bonfill X, Moreno RM, et al. Phlebotonics for venous insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(3):CD003229.

14 Vanscheidt W, Heidrich H, Jünger M, Rabe E. Guidelines for testing drugs for chronic venous insufficiency. Vasa. 2000;29:274.

15 Gohel MS, Davies AH. Pharmacological agents in the treatment of venous disease: an update of the available evidence. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2009;7:303.

16 Sovak M. Grape Extract, resveratrol, and its analogs: a review. J Med Food. 2001;4:93.

17 Badger C, Preston N, Seers K, Mortimer P. Benzo-pyrones for reducing and controlling lymphoedema of limbs. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(2):CD003140.

18 Vanscheidt W, Rabe E, Nazer-Hijazi B, et al. The efficacy and safety of a coumarin-troxerutin combination (SB-LOT) in patients with chronic venous insufficiency: a double blind placebo controlled randomized study. Vasa. 2000;31:185.

19 Carpentier PH, Mathieu M. Evaluation de l’efficacité clinique d’un médicament veinotrope: les enseignements d’un essai thérapeutique avec la diosmine d’hémisynthèse (Diovénor) dans le syndrome de jambes lourdes. J Mal Vasc. 1998;28:106.

20 Biland L, Blatter P, Scheibler P, et al. On the therapy of so-called leg pains. Controlled double-blind study of the therapeutic efficacy of Daflon (in German). Vasa. 1982;11:53.

21 Behar A, Lagrue G, Cohen-Boulakia F, et al. Study of capillary filtration by double labelling I131-albumin and Tc99m red cells. Application to the pharmacodynamic of Daflon 500 mg. Int Angiol. 1988;7(Suppl 2):35.

22 Cospite M, Dominici A. Double blind study of the pharmacodynamic and clinical activities of 5682 SE in venous insufficiency: advantages of the new micronized form. Int Angiol. 1989;8(Suppl 4):61.

23 Barbe R, Amiel M. Pharmacodynamic properties and therapeutic efficacy of Daflon 500 mg. Phlebology. 1992;Suppl 2:41.

24 Galley P, Thiollet M. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of a new veno-active flavonoid fraction (S 5682) in the treatment of symptomatic capillary fragility. Int Angiol. 1992;12:69.

25 Blume I, Langenbahn H, Chamvallins M. Quantification of oedema using the volumeter technique: therapeutic application of Daflon 500 mg in CVI. Phlebology. 1992;2:37.

26 Gilly R, Pillion G, Frileux C. Evaluation of a new venoactive micronized flavonoid fraction (S 5682) in symptomatic disturbances of the venolymphatic circulation or the lower limb. A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Phlebology. 1994;9:67.

27 Amato C. Advantage of a micronized flavonoidic fraction (Daflon 500) in comparison with a micronized diosmin. Angiology. 1994;45:531.

28 Cloarec M, Clement R, Griton P. A double-blind clinical trial of hydroxyethylrutosides in the treatment of the symptoms and signs of CVI. Phlebology. 1996;11:76.

29 Guilhou JJ, Dereure O, Marzin L, et al. Efficacy of Daflon 500 mg on venous ulcer healing: a double blind randomized placebo controlled trial. Angiology. 1997;48:77.

30 Ibegbuna V, Nicolaides AN, Sowade O, et al. Venous elasticity after treatment with Daflon 500 mg. Angiology. 1997;48:45.

31 Chassignolle JF, Amiel G, Lanfranchi G, Barbe R. Activité thérapeutique de Daflon 500 mg dans l’insuffisance veineuse fonctionnelle. JIM. 1999;99(Suppl):32.

32 Shoab SS, Porter JB, Scurr JH, Coleridge-Smith PD. Endothelial activation response to oral micronised flavonoid therapy in patients with chronic venous disease. A prospective study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1999;17:313.

33 Shoab SS, Porter JB, Scurr JH, Coleridge-Smith PD. Effect of oral micronised purified flavonoid fraction treatment on leucocyte adhesion molecule expression in patients with chronic venous disease: a pilot study. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:456.

34 Ramelet AA. Pharmacologic aspects of a phlebotropic drug in CVI-associated oedema. Angiology. 2000;5:19.

35 Olszewski W. Clinical efficacy of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) in edema. Angiology. 2000;51:25.

36 Ramelet AA. Clinical benefits of Daflon 500 mg in the most severe stages of chronic venous insufficiency. Angiology. 2001;52:549.

37 Danielsson G, Jungbeck C, Peterson K, Norgren L. A randomised controlled trial of micronised purified flavonoid fraction vs placebo in patients with CVI. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;23:73.

38 Lyseng-Williamson KA, Perry CM. Micronised purified flavonoid fraction: a review of its use in CVI, venous ulcers and haemorrhoids. Drugs. 2003;63:71.

39 Nicolaides AN. From symptoms to leg oedema: efficacy of Daflon 500 mg. Angiology. 2003;54(Suppl 1):S33.

40 Roztocyl K, Stvrtinová V, Strejcek J. Efficacy of a 6-month treatment with Daflon 500 mg in patients with venous leg ulcers associated with CVI. Int Angiol. 2003;22:1.

41 Coleridge-Smith P, Lok C, Ramelet AA. Venous leg ulcer: a meta-analysis of adjunctive therapy with micronized purified flavonoid fraction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30:198.

42 Simsek M, Burak F, Taskin O. Effects of micronized purified flavonoid fraction (Daflon) on pelvic pain in women with laparoscopically diagnosed pelvic congestion syndrome: a randomized crossover trial. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2007;34:96.

43 Pokrovsky AV, Saveljev VS, Kirienko AI, et al. Surgical correction of varicose vein disease under micronized diosmin protection (results of the Russian multicenter controlled trial DEFANS). Angiol Sosud Khir. 2007;13:47.

44 Veverkova L, Kalac J, Jedlicka V, Wechsler J. Analysis of surgical procedures on the vena saphena magna in the Czech Republic and an effect of Detralex during its stripping, [in Czech]. Rozhl Chir. 2005;84:410.

45 Das L, Subramanyam Reddy G, Pani S. Some observations on the effect of daflon (micronized purified flavonoid fraction of rutaceae aurantiae) in bancroftian filarial lymphoedema. Filaria J. 2003;2:5.

46 Wright DD, Franks PJ, Blair SD, et al. Oxerutins in the prevention of recurrence in chronic venous ulceration: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1269.

47 Kranendonk SE, Koster AM. A double-blind clinical trial of the efficacy and tolerability of O-(β-hydroxyethyl)-rutosides and compression stockings in the treatment of leg oedema and symptoms following surgery for varicose veins. Phlebology. 1993;8:77.

48 Rehn D, Golden G, Nocker W, et al. Comparison between the efficacy and tolerability of oxerutins and troxerutin in the treatment of patients with CVI. Arzneimittelforschung. 1993;10:1060.

49 Vin F, Chabanel A, Taccoen A, et al. Double blind trial of the efficacy of troxerutin on chronic venous insufficiency. Phlebology. 1994;9:71.

50 Diebschlag W, Nocker W, Lehmacher D, Rehn D. A clinical comparison of two doses of O-(β-hydroxyethyl)-rutosides (oxerutins) in patients with CVI. J Pharm Med. 1994;4:7.

51 Poynard T, Valterio C. Meta analysis of hydroxyethyl rutosides in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. Vasa. 1994;23:244.

52 Unkauf M, Rehn D, Klinger J, et al. Investigation of the efficacy of oxerutins compared to placebo in patients with CVI treated with compression stockings. Arzneimittelforschung. 1996;46:478.

53 Incandela L, De Sanctis MT, Cesarone MR, et al. Efficacy of troxerutin in patients with chronic venous insufficiency: a double blind, controlled study. Adv Ther. 1996;13:161.

54 Carlsson K, Patwardhan A, Poullain JC, Gerentes I. Transport and localization of troxerutin in the venous wall. J Mal Vasc. 1996;21(Suppl C):270.

55 Grossmann K. Vergleich der Wirksamkeit einer kombinierten Therapie mit Kompressionstrümpfen und Oxerutin (Venoruton) versus Kompressionsstrümpfe und Placebo bei Patienten mit CVI. Phlebologie. 1997;26:105.

56 Incandela L, Belcaro G, Renton S, et al. HR (Paroven; O-(β-hydroxyethyl)-rutosides) in venous hypertensive microangiopathy: a prospective, placebo controlled, randomized trial. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2002;7(Suppl 1):S7.

57 Petruzellis V, Troccoli T, Candiani C, et al. Oxerutins (Venoruton): efficacy in CVI: a double blind, randomized, controlled study. Angiology. 2002;53:257.

58 Marshall M, Loew D, Schwahn-Schreiber C. Hydroxyethylrutoside zur Behandlung der chronischen Veneninsuffizienz Grad I und II. Phlebologie. 2005;34:157.

59 Diehm C, Vollbrecht D, Amendt K, Comberg HU. Medical edema protection – clinical benefit in patients with chronic deep vein incompetence. A placebo controlled double blind study. Vasa. 1992;21:188.

60 Diehm C, Trampisch HJ, Lange S, Schmidt C. Comparison of leg compression stocking and oral horse-chestnut seed extract therapy in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Lancet. 1996;347:292.

61 Pittler MH, Ernst E. Horse chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency: a criteria-based systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1356.

62 Koch R. Comparative study of Venostasin and Pycnogenol in CVI. Phytotherapy Res. 2002;16:S1.

63 Siebert U, Brach M, Scrozynski G, Berla K. Efficacy, routine effectiveness and safety of horse chestnut seed extract in the treatment of CVI: a meta analysis of randomized controlled trials and large observational studies. Int Angiol. 2002;21:305.

64 Pittler MH, Ernst E. Horse chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004;(2):CD003230.

65 Cappelli R, Nicora M, Di Perri T. Use of extract of Ruscus aculaeatus in venous diseases of the lower limbs. Drugs Exp Clin Res. 1988;4:277.

66 Le Devehat C, Khodabandehlou T, Vimeux M, Dougny M. The effect of Cyclo 3 Fort® treatment on hemorheological disturbances during a provoked venous stasis in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Clin Hemorheol Micorocirc. 1994;14:S53.

67 Parrado F, Buzzi A. A study of the efficacy and tolerability of a preparation containing Ruscus aculeatus in the treatment of CVI of the lower limbs. Clin Drug Invest. 1999;18:255.

68 Jäger KA, Eichlisberger R, Jeanneret CH, Labs KH. Pharmacodynamic effects of Ruscus extract (Cyclo 3 Fort) on superficial and deep veins in patients with primary varicose veins: assessment by duplex sonography. Clin Drug Invest. 1999;17:265.

69 Beltranimo R, Penenory A, Buceta AM. An open label, randomized multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of Cyclo 3 fort versus hydroxyethyl rutoside in chronic venous lymphatic insufficiency. Angiology. 2000;51:535.

70 Bouaziz N, Michiels C, Janssens D, et al. Effect of Ruscus extract and hesperidin methylchalcone on hypoxia-induced activation of endothelial cells. Int Angiol. 1999;18:306.

71 Vanscheidt W, Jost V, Wolna P, et al. Efficacy and safety of a Butcher’s broom preparation compared to placebo in patients suffering from chronic venous insufficiency. Arzneimittelforschung. 2002;52:243.

72 Boyle P. Meta-analysis of clinical trials of Cyclo 3 Fort in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency. Int Angiol. 2003;22:250.

73 Lascasas Porto CL, Milhomens AL, Pires CE, et al. Changes on venous diameter and leg perimeter with different clinical treatments for moderate chronic venous disease: evaluation using Duplex scanning and perimeter measurements. Int Angiol. 2009;28:222.

74 Guex JJ, Enriquez Vega DM, Avril L, et al. Assessment of quality of life in Mexican patients suffering from chronic venous disorder – impact of oral Ruscus aculeatus-hesperidin-methyl-chalcone-ascorbic acid treatment – ‘QUALITY Study’. Phlebology. 2009;24:157.

75 Natali J. Gingkor Fort et maladie veineuse. Angiologie. 1989;102:3.

76 Arnould T, Michiels M, Janssens D, et al. Effect of Ginkor Fort on hypoxia induced neutrophil adherence to human saphenous vein endothelium. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1994;14:95.

77 Zucarelli F. Evaluation de l’efficacité de Ginkor Fort sur la symptomatologie fonctionnelle de l’insuffisance veineuse chronique. Angiologie. 1996;49:1.

78 Janssens D, Michiels C, Guillaume G, et al. Increase of circulating endothelial cells in patients with primary chronic venous insufficiency: protective effect of Ginkor Fort in a randomized double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;33:7.

79 Allegra C, Pollari G, Criscuolo A, et al. L’estratto di centella asiatica nelle flebopatie degli arti inferiori. Ricorca clinco-stratamentale conparativa con un placebo. Clin Ter. 1988;199:507.

80 Cataldi A, Gasbarro V, Viaggi R, et al. Effectiveness of the combination of alpha tocopherol, rutin, melitolotus and centella asiatica in the treatment of chronic venous insufficiency [in Italian]. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2001;49:159.

81 Kiesewetter A, Koscielny J, Kalus U, et al. Efficacy of orally administered extract of red wine leaf AS 195 in chronic venous insufficiency (stages I-II). A randomized double blind, placebo controlled trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 2000;50:109.

82 Constantini A, Bernardi T, Gotti A. Clinical and capillaroscopic evaluation of chronic uncomplicated venous insufficiency with procyanidins extracted from vitis vinifera [in Italian]. Minerva Cardioangiol. 1999;47:39.

83 Petrassi C, Mastromarino A, Spartera C. Pycnogenol in CVI. Phytomedicine. 2000;7:383.

84 Rohdewald P. A review of the French maritime pine bark extract (Pycnogenol), a herbal medication with a diverse clinical pharmacology. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2002;40:158.

85 Arcangeli P. Pycnogenol in chronic venous insufficiency. Fitoterapia. 2000;71:236.

86 Casley-Smith JR. A double-blind trial of calcium dobesilate in chronic venous insufficiency. Angiology. 1988;10:853.

87 Widmer L, Biland L, Barras JP. Doxium 500 in chronic venous insufficiency: a double blind placebo controlled multicenter study. Int Angiol. 1990;9:105.

88 Angehrn F. Efficacy and safety of calcium dobesilate in patients with chronic venous insufficiency: an open label multicenter study. on behalf of the Swiss study group]. Curr Ther Res. 1995;56:346.

89 Arceo A, Berber A, Trevino C. Clinical evaluation of the efficacy and safety of calcium dobesilate in patients with chronic venous insufficiency of the lower limbs. Angiology. 2002;53:539.

90 Allain H, Ramelet AA, Polard E, Bentue-Ferrer D. Safety of calcium dobesilate in chronic venous disease, diabetic retinopathy and haemorrhoids. Drug Saf. 2004;27:649.

91 Iriz E, Vural C, Ereren E, et al. Effects of calcium dobesilate and diosmin-hesperidin on apoptosis of venous wall in primary varicose veins. Vasa. 2008;37:233.

92 Flota-Cervera F, Flota-Ruiz C, Treviño C, Berber A. Randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate the lymphagogue effect and clinical efficacy of calcium dobesilate in chronic venous disease. Angiology. 2008;59:352.

93 Ciapponi A, Laffaire E, Roque M. Calcium dobesilate for chronic venous insufficiency: a systemic review. Angiology. 2004;55:147.

94 Labs KH, Degisher S, Gamba G, Jaeger KA. Effectiveness and safety of calcium dobesilate in treating chronic venous insufficiency: randomized double blind placebo controlled trial. on behalf of the CVI study group]. Phlebology. 2004;19:123.

95 Rabe E, Jaeger K. Multicentre, double blind, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical study to assess the efficacy and safety of Doxium 500 three times daily in patients suffering from CVI CEAP class C3,4 or 5. Phlebologie. 2006;35:A37.

96 Martínez-Zapata MJ, Moreno RM, Gich I, et al. Chronic Venous Insufficiency Study Group. A randomized, double-blind multicentre clinical trial comparing the efficacy of calcium dobesilate with placebo in the treatment of chronic venous disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:358.

97 Hautekeete ML. Severe hepatotoxicity related to benzarone: a report of three cases with two fatalities. Liver. 1995;15:25.

98 Vayssairat M. Placebo-controlled trial of naftazone in women with primary uncomplicated symptomatic varicose veins. and the French Venous Naftazone Trial Group]. Phlebology. 1997;12:17.

99 Zicot M. Etude multicentrique de l’efficacité et de la tolérance de la Naftazone (Mediaven 10 mg). Comparaison de deux schémas posologiques. Rev Med Liège. 1993;158:224.

100 Forconi S, Guerrini M, Pecchi S, et al. Effect of HR(O-(beta-hydroxyl)-rutosides) on the impaired venous function of young females taking oral contraceptives: a strain gauge plethysmographic and clinical open controlled study. Vasa. 1980;9:324.

101 Allaert FA, Vin F, Levardon M. Comparative study of the effectiveness of continuous or intermittent courses of a phlebotonic drug on venous disorders disclosed or aggravated by oral oestrogen-progesterone contraceptives. Phlebologie. 1992;45:167.

102 Serfaty D, Magneron AC. Premenstrual syndrome in France: epidemiology and therapeutic effectiveness of 1000mg of micronized purified flavonoid fraction in 1473 gynecological patients [in French]. Contracept Fertil Sex. 1997;25:85. 1997

103 Lefebvre G, Lacombe C. Venous insufficiency in the pregnant woman. Rheological correction by troxerutin. Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1991;86:206.

104 Marhic C. Clinical and rheological efficacy of troxerutin in obstetric gynaecology. Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1991;86:209.

105 Young GL, Jewell D. Interventions for varicosities and leg oedema in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1998;(1):CD001066.

106 Gouny AM, Horovitz D, Gouny P, et al. Etude d’efficacité et de tolérance des Hydroxyéthyl-rutosides dans le traitement local des symptômes d’insuffisance veineuse survenant au cours des transports aériens. J Mal Vasc. 1999;24:214.

107 Wetzel D, Menke W, Dieter R, et al. Escin/diethylammonium salicylate/heparin combination gels for the topical treatment of acute impact injuries: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, multicentre study. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36:183.

108 Gloviczki PDM, Eklöf B, Moneta GL, Wakefield TW. Handbook of venous disorders: guidelines of the American Venous Forum, 3rd ed. London: Hodder Arnold; 2009. p. 359

109 Kearon C, Kahn SR, Agnelli G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for venous thromboembolic disease: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines, 8th edn. Chest. 2008;133(Suppl 6):454S-545S.

110 Allegra C. Chronic venous insufficiency: the effects of health-care reforms on the cost of treatment and hospitalisation – an Italian perspective. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19:761.