Venepuncture and venous access

Taking a venous blood specimen (venepuncture)

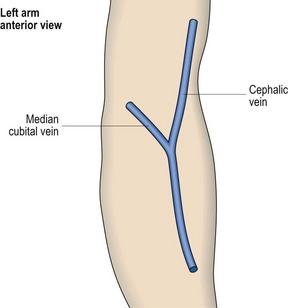

Under normal circumstances blood is most easily taken from a vein in the antecubital fossa; the median cubital vein is preferred (Figs 52.1 and 52.2). It is considerate to ask whether the patient is left- or right-handed and then to choose the non-dominant arm. A tourniquet is applied well proximal to the site. This should cause distension of the veins but not discomfort. Gentle palpation is the best method of identifying a vein and checking its patency. If a suitable vein proves elusive it may help to gently tap the area or to warm the arm in water. The skin over the chosen vein is thoroughly cleaned with antiseptic solution. Usually a 21- or 22-gauge needle is used but a smaller size (e.g. 23) can be used where the veins are fragile, or in children. The syringe should be adequate for the sample – where larger blood samples necessitate more than one syringe a ‘butterfly needle’ may be preferred to a conventional venepuncture needle. The needle is inserted bevel uppermost along the line of the vein at an angle of around 20°. There is a distinctive ‘give’ as the vein is entered. Blood is aspirated into the syringe slowly to avoid haemolysis. The tourniquet is released and the needle withdrawn after a dry swab has been held to the site. Pressure should be applied by the patient or an assistant with the arm held straight or slightly elevated. The needle is removed from the syringe – not resheathed – and placed directly into a sharps container. The specimen is expelled gently from the syringe into the relevant bottles. Mixing with anticoagulant is best achieved by gently inverting the bottle several times – violent shaking will damage the sample. An adhesive plaster can be applied to the venepuncture site (check for allergy) when bleeding has stopped.

Fig 52.1 Veins at the antecubital fossa.

The median cubital vein is preferred for routine venepuncture.

Venous access

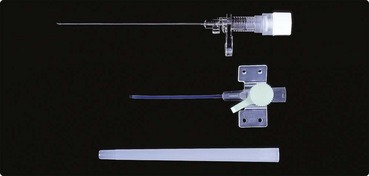

Almost all haematology patients admitted to hospital require a drip to infuse fluids, blood products or drugs. Before inserting a cannula into a vein, an appropriate giving set should be prepared in accordance with instructions and the bag or bottle containing the infusion fluid inverted and hung on the drip stand. The set should be properly primed and all bubbles excluded. The operator must wash hands and wear gloves. It is vital to ensure that the patient is comfortable and fully understands the procedure and that necessary consent is obtained. The choice of cannula depends both on the quality of the veins and the duration and type of infusion. For short-term infusions or small veins a winged metal cannula (butterfly needle) is often suitable. In other circumstances a larger gauge plastic cannula is used (Fig 52.3). In adults, 18–20-gauge catheters provide good flow rates without too much discomfort for the patient.

Central venous cannulation

patients with haematological malignancy receiving intensive chemotherapy

patients with haematological malignancy receiving intensive chemotherapy

patients with thalassaemia having regular blood transfusions

patients with thalassaemia having regular blood transfusions

children with haemophilia A on prophylactic factor VIII treatment.

children with haemophilia A on prophylactic factor VIII treatment.

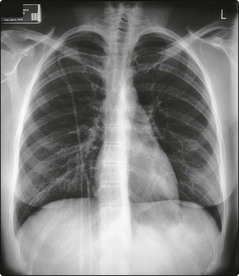

The catheter is normally inserted into the subclavian vein and the location of the distal tip checked on X-ray (Fig 52.4). The proximal end of the catheter can be tunnelled under the skin with an exit site on the anterior chest wall. A catheter cuff within the tunnel promotes the formation of fibrous tissue which helps secure the device. The procedure is usually performed in the operating theatre by a surgeon or anaesthetist. Once in place the catheter may be used for several months. Strict aseptic technique is necessary as infection with coagulase-negative staphylococci is the most common complication.