13 Vascular and endovascular surgery

Atherosclerosis

The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis is complex and not fully understood. The development of atheromatous lesions is aggravated by risk factors including smoking, hypercholesterolaemia, hypertension and diabetes mellitus (see ‘Vascular risk factors and their modification’, below). Low-density lipoproteins and monocyte-derived macrophages accumulate in the tunica intima, forming a fatty streak. In certain susceptible arteries, smooth muscle and inflammatory cells are recruited into the intimal fatty streak, promoting the development of the fibrofatty plaque covered by a collagen fibrous cap.

Atherosclerosis causes symptoms via three mechanisms:

An atheromatous plaque may allow sufficient flow through a vessel to satisfy end-organ demands at rest but cause problems when the flow needs to increase, for example angina on exertion due to stable coronary artery disease. Another example is intermittent claudication (see p. 210). Such symptoms may be unpleasant but not necessarily imminently dangerous.

Aneurysms

Infrarenal abdominal aortic aneurysms

Open repair comprises replacement of the aneurysmal aorta with a Dacron graft sutured into place just below the renal arteries (p. 376). Mortality for elective surgery is around 5–10%, higher for less fit patients. Smoking, reduced FEV, impaired renal function and female gender are adverse risk factors.

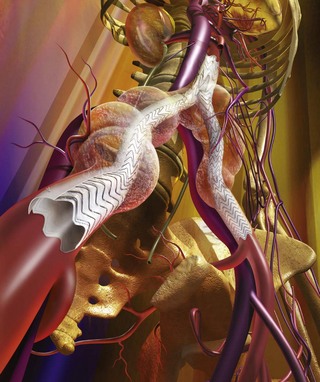

Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) allows a stent-graft to be delivered inside the aneurysm via the femoral artery, then expanded and fixed in position under fluoroscopic guidance (Fig. 13.1). The whole procedure is performed via small groin incisions, or even percutaneously in some cases. Recovery is quicker than for open repair and less fit patients can be treated. The mortality for EVAR is less than 2%, one third of that for open repair. Long term complications of EVAR include endoleaks, graft migration, iliac limb occlusion and aneurysm rupture. Long term surveillance with duplex scanning ± CT is required.

Ruptured AAA (p. 96)

Lower limb ischaemia

Classification of chronic lower limb ischaemia, as described by La Fontaine, is shown in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 The La Fontaine classification for lower limb ischaemia

| Asymptomatic | I |

| Intermittent claudication | II |

| Rest pain | III |

| Ulceration/gangrene | IV |

Causes of lower limb ischaemia

• accelerated atherosclerosis (hyperlipidaemia, hyperhomocysteinaemia, AIDS)

• Buerger’s disease (common in male smokers in the Middle/Far East)

• popliteal entrapment (artery passes medially to medial head of gastrocnemius causing compression; seen in athletes and may progress to permanent arterial damage if untreated)

• fibromuscular dysplasia (most commonly affects carotid and renal arteries but can narrow the iliac arteries in young adults)

• cystic adventitial disease (popliteal artery develops ganglion-like cysts that may connect to the knee joint)

• persistent sciatic artery (associated with atresia of the ileofemoral vessels).

Investigation of lower limb ischaemia

Intermittent claudication

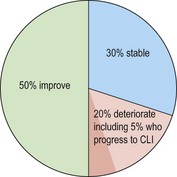

Although unpleasant, IC is a relatively benign condition as far as the leg is concerned. Most patients either stay the same or improve and only a small minority (5%) progress to critical limb ischaemia (Fig. 13.3). Diabetics and patients who continue to smoke have a worse prognosis.

Risk factor modification

In many respects the true significance of IC is not the symptom but the risk of death from other aspects of vascular disease. Claudicants have a mortality around three times that of age-matched controls, mainly due to coronary heart disease, strokes and aneurysms. Attention to vascular risk factors including smoking, hypertension, antiplatelet and statin therapy (see p. 204) is therefore of paramount importance.

Critical lower limb ischaemia

Investigation of limb ischaemia is considered on page 210. Endovascular therapy is usually first-line treatment. Many of these patients die of other problems before the benefits of angioplasty have worn off. The durability of angioplasty is not as good as surgery but the effects may be sufficient to heal the limb and convert rest pain to claudication. Moreover, occlusion of the angioplastied site frequently does NOT result in clinical deterioration and an attempt at angioplasty seems not to prejudice subsequent surgical intervention if required.

The diabetic foot

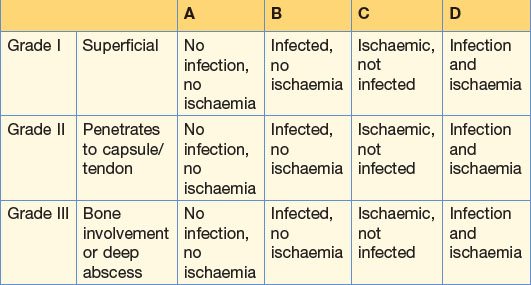

Diabetics are prone to ulceration and infection of the foot which may progress to tissue necrosis requiring amputation. This is due to a combination of vascular disease and neuropathy. Diabetic foot ulcers are classified using the Wagner (Table 13.2) or Texas systems (Table 13.3).

| Grade 0 | No ulcer on a high risk foot |

| Grade 1 | Superficial ulcer |

| Grade 2 | Deep ulcer penetrating to ligaments/muscle but not bone and no abscess formation |

| Grade 3 | Deep ulcer with cellulitis or abscess, often with bone infection |

| Grade 4 | Localised gangrene |

| Grade 5 | Extensive gangrene |

Carotid artery disease

Carotid embolisation

Embolism from the carotid artery may manifest in several ways.

• Asymptomatic. CT and MRI scanning often reveal evidence of multiple small brain infarctions with no history of preceding symptoms.

• Amaurosis fugax. Small emboli which pass through the retinal artery cause the characteristic symptom of a greying out of the vision in the eye on the same side as the source of the embolus. Patients often describe it as a curtain coming down. The vision returns to normal within a few minutes.

• A transient ischaemic attack (TIA). These resolve within 24 hours by definition.

• Strokes result from embolisation of branches of the middle cerebral artery and cause neurological deficit on the contralateral side to the embolising artery. Strokes lasting less than 3 weeks are said to be ‘transient strokes’. Persistent deficits after 3 weeks are ‘established strokes’ and subsequent recovery may be good, moderate or poor.

Venous disease

Varicose veins

Signs

• groin for cough impulse or saphenovarix

• using the tap test: gently feel the lower varicosities while tapping on the proximal saphenous vein. The impulse is transmitted readily down the incompetent trunk

• using the tourniquet (Trendelenburg) test. A popular ritual in clinical examinations but rarely performed by vascular surgeons who use hand-held Doppler and duplex scanning to determine the sites of reflux.

Lymphoedema

The causes of lymphoedema are shown in Table 13.4. There are three types of primary lymphoedema, determined by age of onset.

| Primary | Congenital (symptoms appear as an infant) | Familial (Milroy’s disease) Non-familial |

| Praecox (adolescence) | Familial and non-familial types | |

| Tarda (over 35 years) | Often associated with obesity | |

| Secondary | Infection (commonest cause worldwide but not in the West) | Filariasis (causes elephantiasis) |

| Cancer | Malignant obstruction of lymph nodes by metastases | |

| Surgery/Radiotherapy | Especially to axilla for treatment of breast cancer |

Leg ulceration

Causes

3 ‘Are you on tablets for blood pressure or cholesterol?’ This takes care of the commonest vascular risk factors. Most importantly, find out whether there is pain suggestive of arterial ischaemia, which typically causes pain in bed at night which is relieved by hanging the leg down.

4 ‘Is the ulcer painful, and does your leg feel more comfortable with it up or hanging down?’