Chapter 19 Variations in the duration of pregnancy

PREMATURE OR PRETERM BIRTH

Bacterial vaginosis (see p. 262) has been implicated, which has been associated with an increase in preterm birth two to three times that of women who do not have bacterial vaginosis (15–20% compared with 6%). A Cochrane review of antibiotic therapy to eradicate bacterial vaginosis showed that it was effective in reducing the incidence of preterm birth, but only in women with a previous history of spontaneous premature delivery (RR 0.37). Progesterone as a depot intramuscular injection or as pessaries reduces the recurrence of preterm birth by 35%. Treatment with metronidazole actually increases the rate of preterm birth. It should also be noted that a large number of preterm births follow a spontaneous rupture of the membranes from unknown causes (Table 19.1).

Table 19.1 Causes of curtailment of pregnancy and prematurity

| Cause | Percentage |

|---|---|

| No cause found (including premature rupture of the membrane) | 35–45 |

| Hypertensive disorders | 18–30 |

| Multiple pregnancy | 12–18 |

| Maternal disease | 5–15 |

| Abruptio placentae | 5–7 |

| Placenta praevia | 3–4 |

| Fetal malformations | 1–2 |

PRETERM LABOUR

Management of preterm labour of less than 34 completed weeks

Once labour is established, tocolytic therapy can be administered (Table 19.2) to postpone delivery for at least 24 hours to allow steroid-induced lung maturation to occur. This time can also permit the mother to be transferred to a hospital with neonatal intensive care facilities.

Table 19.2 Tocolytic drugs in the management of preterm labour

| Drug | Dose | Side-Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium-channel blocker | ||

| Nifedipine | 10 mg orally; repeated 20 min later if contractions persist (max. 40 mg in first hour). If contractions cease, 20 mg by mouth 4–6-hourly | Substantially less than with beta agonists. Principal side-effect: headache; others: hypotension, nausea, palpitation |

| Beta agonists | ||

| Salbutamol | Infused at 4 µg/min, increasing by 4 µg/min every 20 min until uterine contractions suppressed; dose maintained for 6 hours and then reduced. Oral salbutamol started 8 mg 6-hourly for 5 days | Tachycardia, palpitations, apprehension, anxiety. Increase in cardiac output. Pressure in the chest |

| Ritodrine | Infused at 50 µg/min increased by 50 µg every 10 min until the contractions cease. Maximum dose 350 µg/min. Run for 24 hours then oral ritodrine 10–20 mg 2–6-hourly | Hypokalaemia. Pulmonary oedema and myocardial ischaemia in 5%. Fluid retention in all women |

Note: Calcium-channel blockers and beta agonists are relatively ineffective if the cervical dilatation is >5 cm.

Before starting tocolytic therapy, the following conditions should apply:

These exclusions mean that fewer than 15% of women in preterm labour should receive tocolytic drugs.

PRELABOUR RUPTURE OF THE MEMBRANES (PROM)

Prelabour (premature) rupture of the membranes may lead to the onset of preterm labour, with or without other causal factors. In most cases the baby is born within 7 days of the rupture; 50% within 2–4 hours, 80–90% by 7 days. Rupture of the membranes after the 35th week is of less clinical significance, and if labour does not start quickly it may be induced by the use of Syntocinon (see p. 190), depending on the state of the cervix. A woman whose cervix is ‘not favourable’ (see p. 189), may prefer to delay induction for 48–72 hours in the anticipation that, during this time, the cervix will ripen and induction will be easier and more successful.

FETAL MATURITY

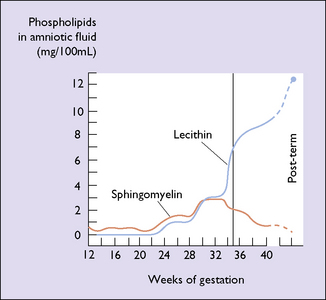

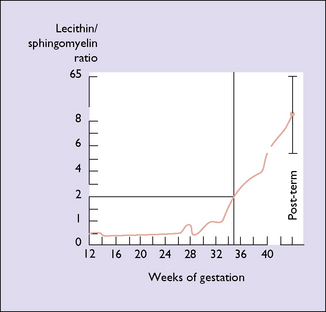

As more women attend for antenatal care early in pregnancy and with the increasing use of ultrasound, the degree of maturity of the fetus is generally known to within 2 weeks. In a few cases the woman does not seek medical attention until the third trimester, at which time the estimation of fetal maturity is less exact. In a mature fetus, hyaline membrane disease is unlikely to develop. Even if it does, neonatologists today have effective treatments. If there is then a need to determine the lung maturity this can be done by measuring the lecithin/sphingomyelin (L/S) ratios. As pregnancy advances the L/S ratio increases (Figs 19.1 and 19.2).

POST-TERM PREGNANCY

Management

If the option of continuing with the pregnancy in the expectation that labour will commence spontaneously is chosen, the welfare of the fetus must be monitored. The mother records fetal movements daily, non-stress cardiotocography is performed twice weekly, and ultrasound examinations are made to measure the volume of the amniotic fluid. An amniotic fluid index of less than 5 is considered abnormal. Umbilical blood flow may also be measured. Abnormalities in these tests (see Ch. 20) may indicate the need for induction of labour or caesarean section.