Variations in appearance of the normal eye

8.1 Anterior eye variations

See online quiz 8.1 and additional online photographs 8.1i–8.5i. Concretions and pinguecula can be found in young adults, but are more common in older patients and are discussed in section 8.2.

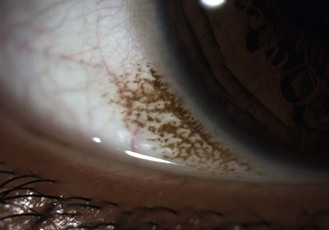

8.1.2 Congenital conjunctival melanosis

Relatively common, bilateral, benign, flat, pigmented areas of conjunctiva, typically near the limbus in young, heavily pigmented eyes (Figure 8.1 and online). The pigmentation is darkest at the limbus with decreasing intensity away from it. It is sometimes simply called complexion-associated conjunctival pigmentation to differentiate it from primary acquired melanosis, which are flat, speckled, brown lesions occurring in patients with European ancestry, do not diminish as they move away from the limbus and can rarely lead to conjunctival melanoma.1

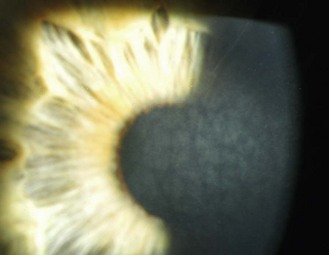

8.1.4 Palisades of Vogt

Limbal epithelial folds that run radially. They are more easily seen in young heavily pigmented eyes and are most prominent in the lower limbus (Figure 8.2 and online). They house limbal epithelial stem cells, which produce epithelial cells to maintain the normal corneal epithelium or replace it in the event of injury.2

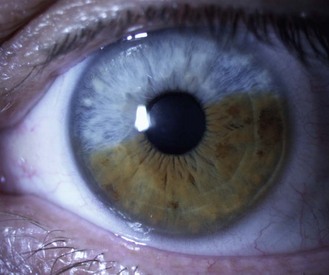

8.1.5 Pigment changes in the iris

Little or no pigment gives ‘blue eyes’. With increasing amounts of pigment, the iris is seen as green, hazel or brown. People with blue irides have greater light scatter than those with more pigmented irides and may suffer more from disability glare in situations such as driving at night.3 Variations in pigment can produce wedge-shaped sections of hyper or hypo-pigmentation (heterochromia, Figure 8.3 and online) in one or both eyes. Hyperpigmented spots (naevi or ‘iris freckles’, Figure 8.4 and online) are common, but should be monitored using photography for changes due to the slight risk of malignant melanoma.

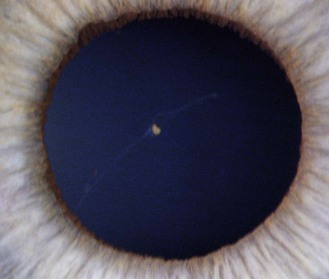

8.1.6 Persistent pupillary membrane

These are strands of the embryonic pupillary membrane that remain into adulthood. One end of the strand inserts into the iris colarette and the other is either attached to the anterior lens capsule or floats in the anterior chamber (Figure 8.5 is a common example, while Figure 8.6 is rare; also online figures).

8.2 Anterior eye changes in older patients

8.2.1 Dermatochalasis

Benign, bilateral drooping of upper lid tissue over the septum or lid margin with age (online figures 8.7i,ii). Cosmetic surgery is sometimes requested. Blepharoplasty or blepharoptosis repair can improve functional vision and may be recommended if the patient reports problems.4

8.2.2 Ectropion and entropion

The eyelid is either turned outward (ectropion) or inward (entropion) due to loose lids so that the inferior lid margin or puncta are not in contact with the eye. The patient may complain of epiphora or be symptomless. It is a common complaint, found in about 3% (ectropion, Figure 8.7) and 2% (entropion) of elderly patients.5

8.2.3 Seborrheic keratosis

One of the most common benign eyelid tumours in the elderly.6,7 Hyperkeratinised, waxy, light grey-brown plaques found over the eyelids and face and appearing to be stuck onto the skin. Typically benign, but should be monitored for changes in size, shape, pigmentation, edge erosion, recurrent infection or inflammation and can be removed for cosmetic reasons. You should reassure the patient and monitor the lesion, ideally using photography.8

8.2.4 Papilloma

The most common benign lesion of the eyelid and often known as a ‘skin tag’.7 They are avascular, epithelial lesions of variable size, shape and colour (amelanotic to black) with a roughened surface reflecting the redundant epithelial cell growth (online figure 8.7iii). Over time, they grow and become attached to the eyelid surface by a stalk (pedunculated), so that the papilloma can be moved back and forth. You should reassure the patient and photograph the cyst, which can be removed for cosmetic reasons.

8.2.5 Sebaceous cysts

Common, benign, yellowish, ‘cheesy’ cyst of variable size (typically 2–5 mm). Superficial cysts are covered by a thin layer of epithelial cells. Multiple small sebaceous cysts are often called milia. Subcutaneous or deep sebaceous cysts are larger (variable, but up to 20 mm) and slightly movable and covered by normal skin. They are caused by blockages to the sebaceous glands, with the blocked pore subsequently becoming filled with the oily sebum (Figure 8.8 and online). You should reassure the patient and photograph the cyst, which can be removed for cosmetic reasons.

8.2.6 Xanthelasma

Bilateral, flat, light brown/yellow, triangular lipid masses with a nasal base, typically found on the inner upper eyelids of elderly patients and especially females (Figure 8.9 and online). They usually have a familial aetiology, but can be linked with atherosclerosis and high cholesterol and any initial diagnosis of xanthelasma should be referred for further investigation. They often reoccur if removed, so the patient should be warned of this if considering cosmetic removal.9

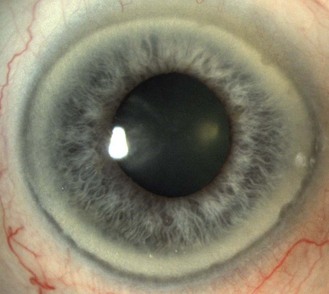

8.2.7 Corneal arcus (previously arcus senilis)

A commonly found, bilateral, 1.0–1.5 mm wide, greyish-white ring or part ring occurring in the periphery of corneas of older patients that is separated from the limbus by a thin ring of clear cornea, the lucid interval of Vogt (Figure 8.10 and online). It is called a corneal arcus rather than a corneal ring as it initially presents as arcs in the inferior and superior poles of the perilimbal cornea before spreading to form a complete ring. The inner edge is typically more diffuse than the sharper outer edge. Its prevalence increases significantly with age after 50 years.10 It is caused by lipid being deposited in the corneal stroma, having permeated from the limbal blood vessels, which become more permeable with age. Corneal arcus may be a sign of systemic hyperlipidaemias if seen in younger adults and any patient with arcus who is below the age of 50 years should be referred for further investigation.

8.2.8 Concretions

Typically asymptomatic, small (1–3 mm), yellow-white calcium lesions found in the palpebral conjunctiva of the upper and lower eyelid.11 They can be found in young adults, but are more common in elderly patients. The majority are superficial, hard and single (Figure 8.11 and online).11 A small percentage of concretions can cause symptoms, likely due to corneal irritation.

8.2.9 Limbal girdle of Vogt

Common, bilateral degenerative condition producing a narrow band of white, crystal-like opacities along the nasal or temporal limbus, typically found in older female eyes (Figure 8.12 and online). Two types are described: type I has a perilimbal clear zone similar to corneal arcus and contains numerous holes, while type II has neither holes nor a clear zone.

8.2.10 Hudson-Stähli line

Common, corneal orangey-brown iron deposition line found close to where the lid margins meet when blinking. The line is generally horizontal, possibly with a slight V-shape in the middle. It can be continuous or segmented and although some texts suggest that the prevalence typically matches the age of the patient, many Hudson-Stähli lines are faint and difficult to see under white light so that this high prevalence seems unlikely. However, they become more visible in cobalt blue (Figure 8.13 and online) or ultra-violet light.12 For this reason you may first notice it during a slit-lamp examination using fluorescein and cobalt blue illumination. Its aetiology is unclear, with the iron possibly arising from the tears, perilimbal blood supply and/or caused by UV radiation and the line/vortex pattern being linked with the position of eyelid closure or the growth and repair patterns of the corneal epithelium.12 Corneal iron deposition can occur in orthokeratology patients and the iron deposition pattern and position appears to change after refractive surgery.13,14

8.2.11 Crocodile shagreen

This is a polygonal pattern of white or grey opacity in the cornea that is visible on direct illumination (Figure 8.14). It takes its name from the pattern of roughly tanned hides that follow the papillae of animals’ skin. Peripheral crocodile shagreen is the most common with a reported clinical incidence of 13.4%.15 The pattern is probably related to the arrangement of corneal fibrils allowing opacities to preferentially occur in some locations. Peripheral shagreen tends to progress towards but never reaching the central cornea. It can vary from faint to striking, and while the latter may be of concern, vision seems unaffected. No treatment is required, and referral is not appropriate.

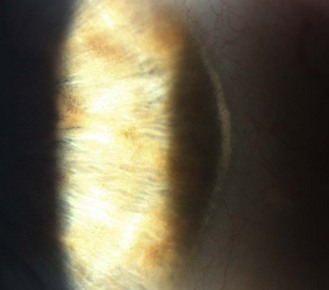

8.2.12 Corneal guttata

These are small excrescences of abnormal basement membrane and collagen fibrillar material from distressed corneal endothelium. They occur in the periphery of all corneas where they are termed Hassall-Henle bodies or ‘warts’ and the prevalence of frank central corneal guttata in those aged over 55 is about 9%, with smoking doubling their likelihood.16 Guttata are often accompanied by a fine pigment dusting, and the endothelial layer is said to take on a beaten metal appearance when viewed with specular reflection or retro-illumination (Figure 8.15). Identification of central corneal guttata may be important in patients undergoing refractive surgery, as mild corneal guttata has been associated with increased risk of complications post surgery.17 The transition from a simple observation of corneal guttata to a diagnosis of Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy occurs when the guttata are accompanied by corneal thickening as evidenced by signs of oedema: striae, folds or clouding. Corneal guttata are a benign clinical finding, as is early Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy.

8.2.13 Pinguecula

A degenerative thickening of the bulbar conjunctiva adjacent to the limbus and often found nasally (Figure 8.16 and online). Although it is seen in adult patients who work outdoors and do not wear sunglasses, its prevalence increases with age and it is very common in the elderly.18 Pingueculae can lift the lids away from the surrounding conjunctiva, leading to a local area of drying and hyperaemia for which artificial tears can be helpful. Given their minimal impact on the patient, and a likelihood to recur, surgical excision is rarely considered. Pinguecula can increase in size with age, so the mainstay of treatment is preventative with UV blockers in spectacles and/or sunglasses.

8.3 Lens and vitreous variations

Vitreous floaters can be found in young adults, particularly the large eyes of moderate to high myopes, but are more common in older patients and are discussed in section 8.4.

8.3.1 Mittendorf dot

Seen as a small black dot in fundal retro-illumination (Figure 8.17 and online) and a white dot on the posterior capsular surface in direct illumination. It is usually displaced nasally or inferior-nasally and it is a remnant of the attachment of the hyaloid canal to the posterior lens surface. The hyaloid artery provides nutrients to the developing lens in the growing foetus and is typically fully regressed before birth (![]() but see video 8.1 which shows a full hyaloid artery in a young adult). It runs from the ophthalmic artery at the optic disc to the crystalline lens where it spreads over both surfaces of the lens in a capillary net or tunica vasculosa lentis.

but see video 8.1 which shows a full hyaloid artery in a young adult). It runs from the ophthalmic artery at the optic disc to the crystalline lens where it spreads over both surfaces of the lens in a capillary net or tunica vasculosa lentis.

8.3.2 Epicapsular stars

Small, light brown or tan star shaped deposits on the anterior lens surface (Figure 8.18 and online) that are remnants of the tunica vasculosa lentis (section 8.3.1). They can be bilateral or unilateral and single or multiple.

8.3.3 Zones of discontinuity

The slit-lamp appearance of the normal adult lens shows a series of zones of clear media in both the anterior and posterior lens cortex delineated by a curved line of scattered light (Figure 8.19 and online). These zones are made up of lens fibre layers with different scattering properties, likely due to different refractive indices in the continually growing lens cortex. Koretz and colleagues suggested that an adult lens typically contains three zones that originate from lens growth at approximate ages of 5, 10 and 20 years, with a fourth zone often appearing after the age of 40.19

8.3.4 Y-sutures

The lens is formed by the meeting of fibres that arch over the lens equator and join with other fibres to form branching suture lines which take on an upright ‘Y’ appearance anteriorly and an inverted ‘Y’ appearance posteriorly (Figure 8.19 and online) in the foetal lens. The sutures are visible because of the large amount of light scatter caused by the non-uniform shape and size of the lens fibre ends. These lens sutures become progressively more complex during distinct periods of lens growth. In early childhood, simple star sutures are formed. In adolescence and adulthood, star (9 branches) and complex star (12 branches) sutures are formed, but these are much more difficult to see.20

8.4 Lens and vitreous changes in older patients

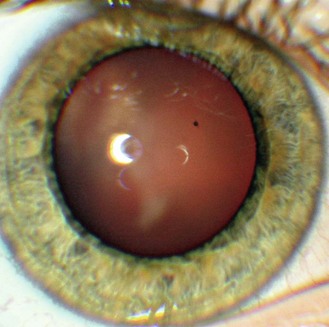

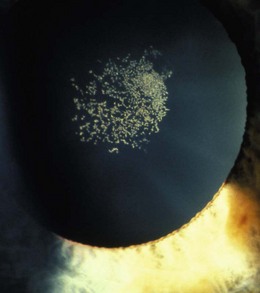

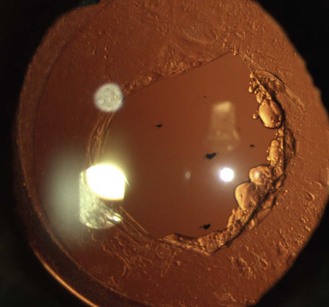

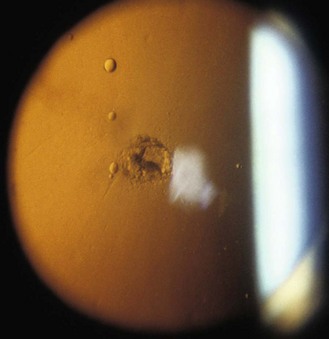

8.4.1 Posterior subcapsular (PSC) cataract

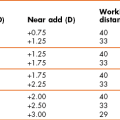

PSC cataract presents at the back of the lens just in front of the posterior capsule. In the age-related type, vacuoles are found in the early stages (Figure 8.20 and online). Later, there is a posterior migration of epithelial cells from the lens equator to the posterior pole, where they form the balloon or bladder cells of Wedl. Large particle scattering is increased by the many organelles in the epithelial cells. To categorise a cataract as PSC, an optical section technique is required, although PSC cataract is best viewed through a dilated pupil using retro-illumination from the fundus.

Fig. 8.20 A small posterior subcapsular cataract and several vacuoles seen in fundal retro-illumination.

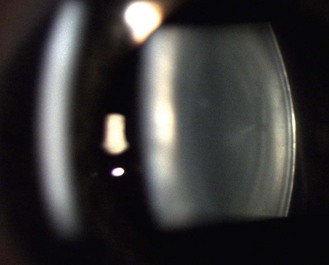

PSC cataract typically presents earlier than the other morphological types, at about age 55 years, and are associated with diabetes, other ocular diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa and uveitis, after ocular trauma and are found as a side effect of systemic drugs such as oral corticosteroids.21 PSC cataracts can cause a dramatic reduction in vision with pupil constriction because they are generally centrally positioned within the pupil. These cataracts can hide behind the corneal and lens reflexes when viewed through an undilated pupil and be missed (Figure 8.21 and online). Clinicians have been successfully sued for missing PSC cataracts in patients with no symptoms at the time of the eye examination but whom subsequently had holidays ruined due to poor vision in a brighter, sunnier climate.

8.4.2 Nuclear cataracts

These present as a homogenous increase in light scatter in the lens nucleus and can be associated with an increased yellowing turning to brunescence (Figure 8.22 and online), which is indicative of blue wavelength-dependent light absorption. The use of a slit-lamp optical section technique is the only accurate way of detecting and assessing nuclear cataract and it is best performed with a dilated pupil, although is still possible undilated.

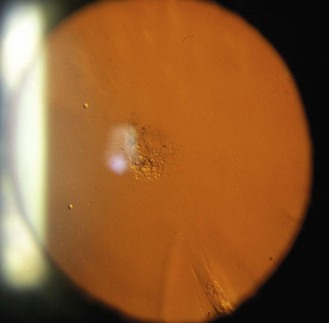

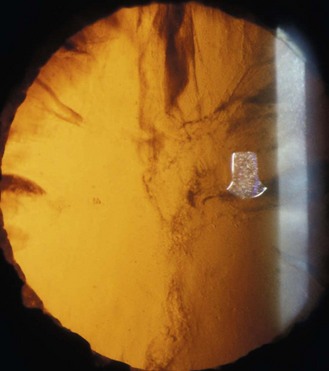

8.4.3 Cortical cataract

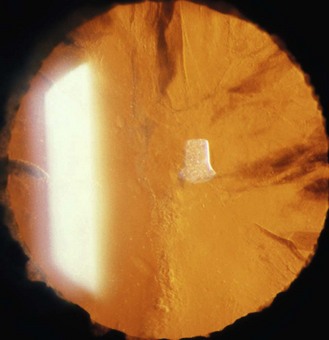

Cortical cataracts are wedge shaped opacities found in the anterior and/or posterior lens cortex. Vision is only affected if the cortical spokes enter the pupillary area and vision therefore varies depending on pupil size. Cortical opacities are most often found in the inferior-nasal part of the lens, which may reflect ultra-violet B radiation involvement in their aetiology.22 Opacification is due to the scattering of light when it meets irregular interfaces between regions of different refractive index. Cortical opacities are best seen using retro-illumination from the fundus, when the cortical opacities appear black against the red fundal glow (Figure 8.23 and online). The brightest reflection from the fundus is obtained when the illuminating beam strikes the optic nerve head, so that typically the illumination system is placed on the temporal side of the biomicroscope. The slit-lamp illumination beam size, shape and position can be altered to avoid the cortical opacities on its way to the fundus. Some slit lamps allow a half-moon shape illumination beam that can be placed inside the edge of the pupil. In some cases you may need to view the opacities with the illumination in two positions (Figures 8.23 and 8.24). Retro-illumination gives an overall view of the cataract, although note that the depth of focus is usually not sufficient to provide an assessment of both the anterior and posterior lens at the same time, particularly with higher magnification, so that separate assessments are required. The cataracts appear white in direct illumination and are often associated with water clefts, which are optically clear wedges that can be seen with slit-lamp biomicroscopy. Using optical sections to view cortical cataracts is much less useful as it can show large amounts of light scatter due to backward light scatter and reflections that do not cause vision loss and an overall view of the cataract is only possible by mentally combining the views of the many optical sections.

Fig. 8.24 The same cortical cataract as in Figure 8.23 with the illumination beam now on the right side of the pupil. Notice the difference in appearance of the same cataract in the two photographs.

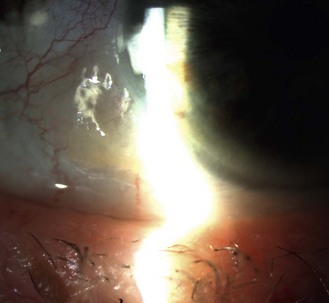

8.4.4 Intra-ocular lenses and posterior capsular remnants

Given the very high rate of cataract surgery in the developed world, you will often examine a pseudophakic patient with an intra-ocular lens and an intact posterior capsule. This capsule can thicken, or form a scaffold for residual lens cell proliferation. If posterior capsular opacification encroaches on the pupillary area and causes visual problems, referral for YAG laser capsulotomy should be suggested. After YAG capsulotomy, a hole in the capsular remnants will be visible (Figure 8.25 and online). As for PSC cataracts, capsular remnants are best seen using retro-illumination from the fundus.

8.4.6 Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD)

With ageing, liquefaction and shrinkage (syneresis) occur and this leads to posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). PVD is common after the age of 50, with the prevalence being similar to the patient’s age, with even greater prevalence after cataract surgery. Detachment of the vitreous from the retina is a slow process, so when the patient is examined the PVD may be complete or incomplete. Determination of whether a PVD is complete or incomplete can only be done with binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy through a dilated pupil. Eventually, all PVDs progress to complete detachment of the vitreous from the sensory retina with collapse of the gel. Many PVDs are asymptomatic, but symptoms are classically a sudden onset of flashes of light, due to tugging on the vitreo-retinal adhesion, and floaters.23 After the vitreous detaches from the optic nerve head, it can be seen as a ring-like vitreous floater known as a Weiss ring (Figure 8.26 and online).

8.5 Optic nerve head variations

See online quiz 8.3 and additional online photographs 8.31i–8.38ii.

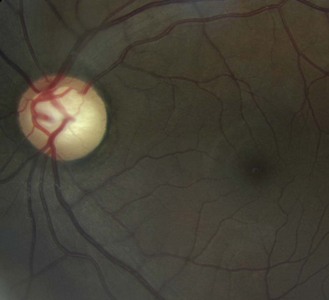

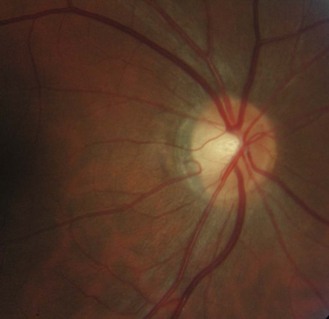

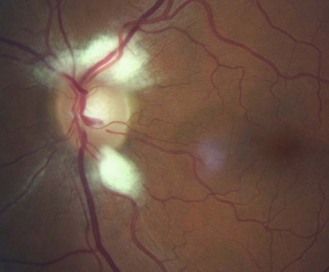

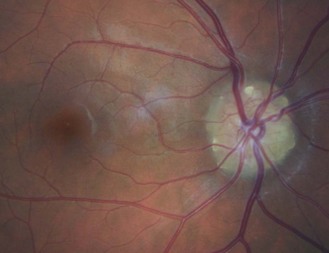

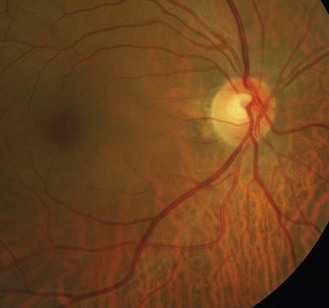

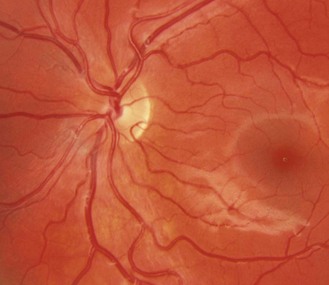

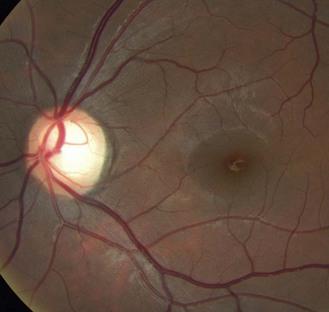

8.5.1 Optic nerve head size and shape

The optic nerve head or disc comes in a variety of shapes and sizes (Figures 8.27–8.30 and online quiz 8.3; note that relative size is affected by the degree of magnification of the book figures). Discs have been shown to be smaller in Caucasians, and progressively larger in Mexicans, Asians and African Americans.24 Disc size is larger in myopes beyond –8 D and smaller in hyperopes greater than +4 D.25 Oval discs are often found with corneal astigmatism and the direction of the longest optic disc diameter can indicate the axis of astigmatism (Figure 8.30).26

Fig. 8.27 Small optic disc with minimal cupping of a young Caucasian patient. Note the relative difficulty of detecting parts of the disc margin (compare with figure 8.28).

Fig. 8.28 Large optic disc and large cupping (CD ratio ~0.60), a visible nerve fibre layer and macular pigmentation of a young, slightly myopic Asian patient.

8.5.2 Optic cupping

The central proportion of the nerve head usually contains a depression called the ‘cup’. This is often associated with an area of pallor due to the lamina cribrosa reflecting through in the absence of axons and their associated capillaries. However, in some cases the cup can extend beyond the area of pallor, so that this should not be used as an indicator of cup size during 2D evaluations such as provided by direct ophthalmoscopy. Rather the kinking of blood vessels as they pass over the edge of the cup should be used as an estimate of the cup position. As discussed above, discs can vary considerably in size, yet approximately the same number of axons (about one million) leave the eye via the optic nerve head. Therefore, large optic discs typically have larger cupping because of the absence of axons in the middle of the disc as the neurons leave the retina in the larger rim tissue of larger discs. The physiological cup-to-disc ratio (CDR) is normally less than 0.60, but is relative to the size of the disc so that smaller cupping should be seen in a small-sized disc and larger cupping is expected in large discs (Figures 8.27–8.29 and online quiz 8.3). For this reason, a 0.30 CDR in a small disc may be more indicative of glaucoma than a 0.70 CDR if it is in a large-sized disc, highlighting the importance of assessing disc size.27 The vertical CDRs indicated for the photographs presented here are based on the 2-D diagrams. The optic nerve heads and cups of the two eyes are typically mirror images of each other and differential diagnosis of many optic nerve head anomalies is provided by an inter-eye comparison.

8.5.3 Spontaneous venous pulsation

See online video 8.2.![]() Present in about 90% of adult eyes with careful observation and most obvious at the point of entry of the central retinal vein into the optic nerve.28 It is caused by the intracranial pressure pulse which acts on the central retinal vein as it passes through the subarachnoid space where it leaves the optic nerve.29 It can be useful to record its presence as its cessation is a sensitive marker of raised intracranial pressure and can help in the differential diagnosis of true papilloedema (it is absent) from pseudopapilloedema (it is present).28 Venous pulsation is best seen with high magnification (15× with direct ophthalmoscopy or fundus biomicroscopy using lenses and slit-lamp settings to gain a similar magnification) and mydriasis.28

Present in about 90% of adult eyes with careful observation and most obvious at the point of entry of the central retinal vein into the optic nerve.28 It is caused by the intracranial pressure pulse which acts on the central retinal vein as it passes through the subarachnoid space where it leaves the optic nerve.29 It can be useful to record its presence as its cessation is a sensitive marker of raised intracranial pressure and can help in the differential diagnosis of true papilloedema (it is absent) from pseudopapilloedema (it is present).28 Venous pulsation is best seen with high magnification (15× with direct ophthalmoscopy or fundus biomicroscopy using lenses and slit-lamp settings to gain a similar magnification) and mydriasis.28

8.5.4 Lamina cribrosa

Seen in about 30% of eyes as grey dots at the bottom of the optic cup (Figure 8.31, 8.40 and online).30 It is a sieve-like connective and glial tissue that is continuous with the scleral canal. It is more visible in larger discs and larger cups.30

8.5.5 Cilio-retinal artery

Found in about 15–20% of normal eyes as an artery that hooks out of the temporal edge of the disc and runs towards the macula (Figure 8.31 and online). Its shape gives it the nickname of the ‘Shepherd’s crook’. It is derived from the short posterior ciliary system or choriocapillaris rather than the central retinal artery and it becomes most relevant after a central retinal artery occlusion, when it saves the retina around its distribution. Of course, the cilio-retinal artery can itself become occluded.

8.5.6 Nerve fibre layer striations

These are brightest at the superior and inferior poles, where the nerve fibre layer is thickest, and are best seen in young patients, particularly those with heavily pigmented fundi (Figure 8.27–8.33). The striations are caused by the tubes of astrocytes that surround the retinal ganglion cell axon. Fundus photography, particularly digital, may provide a better assessment of the nerve fibre layer than fundus biomicroscopy.31 Nerve fibre layer striations are best seen with the green (red-free) filter as the lower wavelengths do not penetrate the nerve fibre layer and are more readily reflected back.

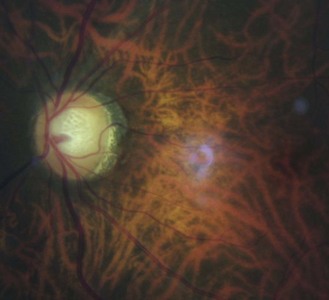

8.5.7 Tilted discs and optic disc malinsertion

The tilt can be seen with the 3D view of fundus biomicroscopy. With direct ophthalmoscopy it is seen as an oval disc whose edges may not be exactly focussed simultaneously. Optic disc malinsertion is a simple insertion of the optic nerve at an acute angle and without the appearance of rotation of the optic nerve, nasal staphyloma or situs inversus. The malinsertion is almost always bilateral and the malinserted discs are mirror images of each other, typically elevated nasally, tilting downwards temporally and with a temporal scleral and/or choroidal crescent. Photographs from the right and left eyes of a patient with malinserted discs are shown in Figures 8.32 and 8.33 and online.

Fig. 8.32 Tilted disc with the nasal side raised and blood vessels nasally displaced. There is a temporal choroidal crescent, slightly tessellated fundus and visible nerve fibre layer.

Fig. 8.33 Fellow eye of Figure 8.32 showing a tilted disc.

Tilted disc syndrome is more rare, with the disc or discs commonly tilted inferior nasally with a nasal staphyloma (bulging of the sclera) and situs inversus, where the temporal blood vessels first course towards the nasal retina before sharply changing course (tilted disc syndrome in Figure 8.34 and a normal disc in the fellow highly myopic eye in Figure 8.35). Tilted discs are thought to be caused by an incomplete closure of the embryonic foetal fissure, similar to the aetiology of a coloboma.32 The condition is benign, although the area of nasal staphyloma can produce a temporal visual field defect. Tilted discs are associated with corneal astigmatism and myopia and the direction of the longest optic disc diameter can indicate the axis of corneal astigmatism.26

Fig. 8.34 Tilted disc syndrome and highly visible choroidal blood vessels in a young, highly myopic and astigmatic Caucasian patient. The disc is tilted inferior nasally with situs inversus.

Fig. 8.35 Fellow eye of Figure 8.34 showing a normal disc and highly myopic Caucasian fundus.

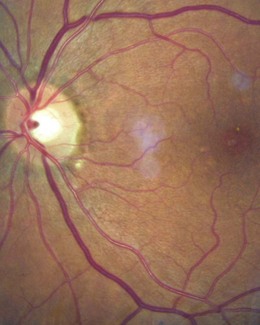

8.5.8 Peripapillary atrophy (PPA)

PPA can be categorised into zone alpha and beta.33 Zone Beta PPA is found adjacent (Bordering) to the disc and is present in about 15% of normal eyes (Figure 8.36 and online). The RPE and choriocapillaris are lost and all that is visible are the large choroidal vessels and sclera. Zone alpha is present in nearly all normal eyes and is characterised by irregular hyper and hypopigmented areas in the RPE, either on their own or surrounding zone beta PPA. PPA is most commonly found at the temporal edge of the disc. It should be differentially diagnosed from high myopic atrophy and malinserted optic discs.

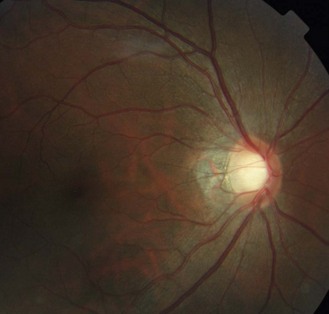

8.5.9 Myelinated nerve fibres

Found in about 1% of patients and represents myelin sheathing of the optic nerve fibres that extends beyond the lamina cribrosa and presents a superficial, white, feathery opacification which hides any underlying retinal blood vessels. They are usually continuous with the optic nerve head (Figure 8.37 and online), although small discrete patches of myelinated nerve fibres can appear and may mimic a cotton wool patch. They are typically benign, although may cause visual field loss at threshold. In most cases, myelinated nerve fibres remain unchanged over time. However, loss of myelinated nerve fibres may occur due to a central demyelinating process or the result of direct axonal destruction or nerve fibre layer ischaemia.34

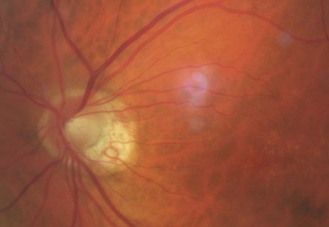

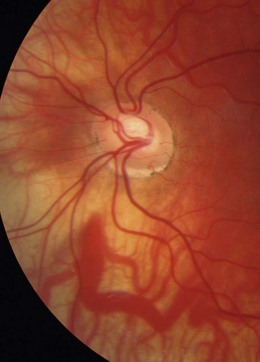

8.5.10 Drusen of the disc

A familial, typically bilateral condition, found in about 0.3% of patients, which becomes more obvious with age.35 In children, they may be buried in the nerve head and not seen and the disc appears swollen, so that the condition is sometimes called pseudopapilloedema. They are golden, autofluorescent, glowing, calcific globular deposits that sit in front of the lamina cribrosa (Figure 8.38 and online). They are typically found in small discs with little or no cupping and this appearance can mask signs of early glaucoma. Although typically benign they can shear blood vessels and/or nerve fibres, leading to haemorrhages (2–10%) and visual field loss (~75%), some of which can be progressive, so that visual field monitoring is essential.35

8.6 Fundus variations

8.6.1 Fundus pigmentation

Fundus pigmentation typically mimics skin pigmentation. Compare the Asian and African-Caribbean fundi in Figures 8.28–8.30 to the Caucasian fundus in Figure 8.27. With a lightly pigmented or thin (typically myopic) RPE, the choroidal vessels and choroidal pigmentation can be seen (Figures 8.34 and 8.35).

8.6.2 Macular pigmentation

The macula lutea area contains a yellow-brown pigment, although the amount is highly variable between individuals, and is most obvious in highly pigmented eyes (Figures 8.30, 8.39 and online). A bright reflex may be seen at the foveola in younger patients, as the ophthalmoscope light is reflected back from the foveal pit.

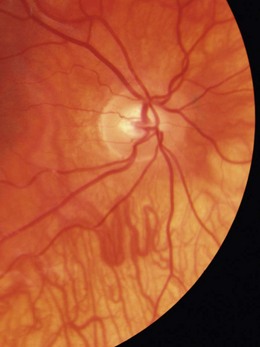

8.6.3 Congenital vascular tortuosity

Most commonly bilateral and involving both arteries and veins and all quadrants (Figure 8.39 and online). Acquired tortuosity, particularly of veins, is less common than the congenital condition, but should be considered as it is connected with a variety of ocular and systemic diseases. For this reason, eyes with very tortuous vessels should ideally be photographed and monitored.

8.6.4 Tessellated or tigroid fundus

A thin RPE allows the red choroidal vessels and heavily pigmented choroid to be seen and can give a tiger stripe appearance (Figures 8.40 and 8.41). It is more commonly seen with the thin retina of myopic patients.36

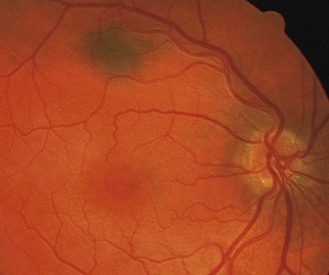

8.6.5 Choroidal naevus

A commonly found localised area of choroidal pigmentation, also known as a benign choroidal melanoma. They can be described to patients as a freckle on the back of their eye. They have a prevalence up to 30%, although they can be easily missed with the direct ophthalmoscope given its limited field of view. They appear grey as your view of a choroidal naevus is filtered through the RPE and sensory retina (Figure 8.42 and online). Naevi can be flat or raised, with drusen often appearing on the surface with age. They vary in size, although the vast majority are less than two disc diameters. All naevi should be routinely monitored, preferably using photography, as they can rarely transform into a malignant melanoma.

8.6.6 RPE window defect

A fairly common, benign, yellow-white, well-circumscribed dot or circle (Figure 8.43) found throughout the retina, but particularly in the mid-peripheral fundus (2 disc diameters either side of the equator of the eye). It is caused by the absence of melanin in the RPE in a localised area. It is typically not associated with surrounding RPE hyperplasia (increase in the number of RPE cells) as would be seen with a chorioretinitis. It is easily differentiated from the red-brown retinal hole, which often has a surrounding cuff of retinal oedema or RPE hyperplasia. RPE window defects can enlarge with age, but this is of no concern.

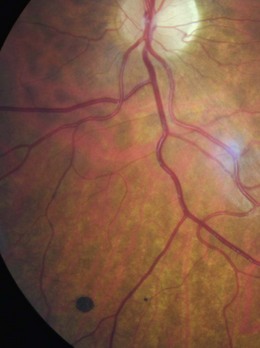

8.6.7 Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (CHRPE)

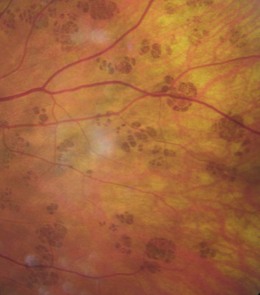

Pronounced as ‘chirpy’, these are congenital, unilateral, flat, typically round or oval patches of pigment (‘birthmarks’) found in the peripheral retina (Figure 8.44). They are typically darker than naevi (although they can be grey, brown or black) with sharply defined edges and consist of a layer of hyperpigmented RPE cells over a thickened Bruch’s membrane. They are found in about 1.2% of the optometric population (although many would not be seen with the limited view provided by a direct ophthalmoscope) with about one-half having a depigmented halo just inside the border (this gives rise to the alternative name of halo naevi) and about one-half containing hypopigmented lacunae, which are areas of chorioretinal atrophy.37 Increasing atrophy may lead to slight enlargement of the lesion. A group of small pigment patches in an isolated quadrant of the peripheral fundus are known as ‘bear tracks’ (Figure 8.45) given their characteristic clustering. Although commonly referred to as a type of CHRPE, bear tracks do not show haloes or lacunae and are histolopathologically different to CHRPE.38 Both are benign features and cause no problem other than the possible loss of the overlying retinal receptors with associated visual field loss. As with choroidal naevi, CHRPE need to be differentially diagnosed from malignant melanoma and require regular monitoring and documentation. With age, the central pigment of a CHRPE can be lost (‘sunburst’ effect). The lesion should preferably be photographed or otherwise drawn with an approximation of its size and position.

8.7 Fundus changes in older patients

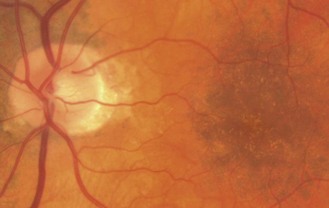

8.7.1 Macular pigmentary changes

Pigmentary changes occur at the macula with age, with increased disorganisation of the RPE and areas of depigmentation and pigment clumping (Figure 8.46, compare with maculae from young adults, Figures 8.27–8.30). These changes need not cause losses of visual function, but can progress to early age-related maculopathy.

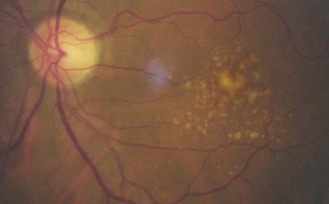

8.7.2 Drusen

Small, circular yellow or yellow-white dots, commonly seen around the macula (Figure 8.47), disc (Figure 8.38) and more peripherally. They consist of deposits lying between Bruch’s membrane and the basement membrane of the retinal pigment epithelium. Large drusen should arouse a greater level of concern as they indicate a greater level of RPE compromise and are associated with the development of exudative age-related maculopathy.

8.7.3 Retinal blood vessels

Changes to the retinal blood vessels can occur with normal ageing or can indicate early signs of hypertensive retinopathy.39 The more significant the changes at an early age, the more likely the changes are early hypertensive changes. Arteriolar narrowing and hardening of the arteries occurs with increasing age and can cause a slight broadening of the reflex on the arterioles. Arteriosclerotic changes can lead to changes to the veins at artery–vein crossings, with 90-degree crossings and nipping of the vein on the distal side of the artery (Figures 8.46 and 8.48), becoming increasingly common.

8.8 Peripheral fundus variations

8.8.1 Vortex vein ampullae

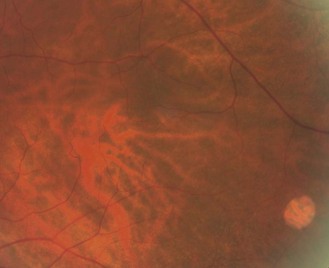

The ampullae are the dilated sacs of the vortex veins, which receive blood from the tributaries of the vortex system, and are red-orange octopus or spider shaped, often surrounded by pigment. The ampullae are found at the equator, with at least one per quadrant, typically in the four oblique meridians, and up to ten in each eye. They are most easily seen in a lightly pigmented eye (Figure 8.49).

8.8.2 Ciliary nerves and arteries

Two long posterior ciliary nerves bisect the superior and inferior fundus at the 3 and 9 o’clock positions in the fundus periphery and 10–20 short posterior ciliary nerves can be seen away from the horizontal meridian. They appear as faint, yellow-white short lines (Figure 8.50), often with pigmented borders. The long posterior ciliary arteries run below the corresponding ciliary nerve in the temporal retina and above it in the nasal retina. The short posterior ciliary arteries may have pigmented margins.

8.9 Peripheral fundus changes in older patients

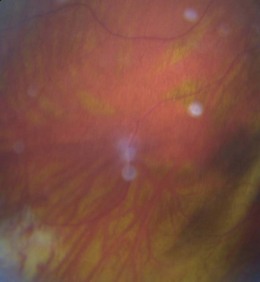

8.9.1 Pavingstone degeneration

This primary chorioretinal atrophy, with depigmented areas surrounded by RPE hyperplasia, is found in about 25% of patients over 20 (Figure 8.50), but increases with age. If the lesions coalesce, the underlying choroidal vessels may be seen (Figure 8.51). It is often bilateral with about 75% of lesions being found in the inferior nasal quadrant. It is thought to be caused by occlusion of some of the peripheral choriocapillaris vessels.

8.10 Myopic eyes

The majority of myopia is due to an increased axial length, so myopic eyes are big eyes. Pathological myopia is well-recognised, but non-pathological myopic eyes also show typical changes.40 The anterior angle is typically deeper in myopes and the vitreous is more liquefied and degenerative the higher the myopia. Therefore, there is a higher prevalence of vitreous floaters and a greater likelihood of posterior vitreous detachment at an earlier age. If the RPE is pulled away from the disc in long myopic eyes, a crescent-shaped section of the choroid (choroidal blood vessels and pigment) can be seen (Figures 8.31–8.33). If both the RPE and choroid are pulled away from the disc, a white scleral crescent can be seen. These crescents are typically seen along the temporal edge.36 The optic disc is typically larger in high myopia (greater than –8 D) often with a larger cup-to-disc ratio.25 The retina of the large myopic eye is relatively thin. This leads to a greater prevalence of tessellated/tigroid fundi (Figures 8.40, 8.41), visible choroidal vessels (Figures 8.34, 8.35) and lattice degeneration (Figure 8.52).36

References

1. Gloor, P, Alexandrakis, G. Clinical characterization of primary acquired melanosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:1721–1729.

2. Dua, HS, Azuara-Blanco, A. Limbal stem cells of the corneal epithelium. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;44:415–425.

3. Nischler, C, Michael, R, Wintersteller, C, et al. Iris color and visual functions. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2013:195–202.

4. Cahill, KV, Bradley, EA, Meyer, DR, et al. Functional indications for upper eyelid ptosis and blepharoplasty surgery: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2510–2517.

5. Damasceno, RW, Osaki, MH, Dantas, PE, Belfort, R, Jr. Involutional entropion and ectropion of the lower eyelid: prevalence and associated risk factors in the elderly population. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:317–320.

6. Chi MJ, Baek SH. Clinical analysis of benign eyelid and conjunctival tumors. Ophthalmologica 2006; 220:43-51.

7. Deprez, M, Uffer, S. Clinicopathological features of eyelid skin tumors. A retrospective study of 5504 cases and review of literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:256–262.

8. Kersten RC, Ewing-Chow D, Kulwin DR, Gallon M. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of cutaneous eyelid lesions. Ophthalmology 1997;104:479–84.

9. Rohrich RJ, Janis JE, Pownell PH. Xanthelasma palpebrarum: a review and current management principles. Plast Reconstr Surg 2002;110:1310–4.

10. Vurgese, S, Panda-Jonas, S, Saini, N, et al. Corneal arcus and its associations with ocular and general parameters: the Central India Eye and Medical Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 52, 2011. [9636-4963].

11. Haicl P, Jankova H. Prevalence of conjunctival concretions. Cesk Slov Oftalmol 2006;61:260–4.

12. Every, SG, Leader, JP, Molteno, AC, et al. Ultraviolet photography of the in vivo human cornea unmasks the Hudson-Stahli line and physiologic vortex patterns. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3616–3622.

13. Rah, MJ, Barr, JT, Bailey, MD. Corneal pigmentation in overnight orthokeratology: a case series. Optometry. 2002;73:425–434.

14. Vonthongsri, A, Chuck, RS, Pepose, JS. Corneal iron deposits after laser in situ keratomileusis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:85–86.

15. Ansons, AM, Atkinson, PL. Corneal mosaic patterns – morphology and epidemiology. Eye. 1989;3:811–815.

16. Zoega, GM, Fujisawa, A, Sasaki, H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for cornea guttata in the Reykjavik Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:565–569.

17. Moshirfar, M, Feiz, V, Feilmeier, MR, Kang, PC. Laser in situ keratomileusis in patients with corneal guttata and family history of Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31:2281–2286.

18. Rashima, A, Ramesh, SVE, Lokapavani, V, et al. Prevalence and associated factors for pterygium and pinguecula in a South Indian population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32:39–44.

19. Koretz, JF, Cook, CA, Kuszak, JR. The zones of discontinuity in the human lens: development and distribution with age. Vision Res. 1994;34:2955–2962.

20. Kuszak, JR, Peterson, KL, Sivak, JG, Herbert, KL. The interrelationship of lens anatomy and optical quality. II. Primate lenses. Exp Eye Res. 1994;59:521–535.

21. Vasavada, AR, Mamidipudi, PR, Sharma, PS. Morphology of and visual performance with posterior subcapsular cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:2097–2104.

22. Graziosi, P, Rosmini, F, Bonacini, M, et al. Location and severity of cortical opacities in different regions of the lens in age-related cataract. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1698–1703.

23. Hikichi, T, Trempe, CL. Relationship between floaters, light-flashes, or both, and complications of posterior vitreous detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;117:593–598.

24. Jonas, JB, Budde, WM, Panda-Jonas, S. Ophthalmoscopic evaluation of the optic nerve head. Surv Ophthalmol. 1999;43:293–320.

25. Jonas, JB. Optic disk size correlated with refractive error. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:346–348.

26. Jonas, JB, Kling, F, Grundler, AE. Optic disc shape, corneal astigmatism, and amblyopia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1934–1937.

27. Garway-Heath, DF, Ruben, ST, Viswanathan, A, Hitchings, RA. Vertical cup/disc ratio in relation to optic disc size: its value in the assessment of the glaucoma suspect. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1118–1124.

28. Jacks, AS, Miller, NR. Spontaneous retinal venous pulsation: aetiology and significance. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:7–9.

29. Morgan, WH, Lind, CR, Kain, S, et al. Retinal vein pulsation is in phase with intracranial pressure and not intraocular pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:4676–4681.

30. Healey, PR, Mitchell, P. Visibility of lamina cribrosa pores and open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:871–872.

31. Blumenthal, EZ, Weinreb, RN. Assessment of the retinal nerve fiber layer in clinical trials of glaucoma neuroprotection. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45:S305–S312.

32. Sowka, J, Aoun, P. Tilted disc syndrome. Optom Vision Sci. 1999;76:618–623.

33. Jonas, JB, Budde, WM. Diagnosis and Pathogenesis of Glaucomatous Optic Neuropathy: Morphological Aspects. Prog Ret Eye Res. 2000;19:1–40.

34. Williams AJ, Fekrat S. Disappearance of myelinated retinal nerve fibers after pars plana vitrectomy. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;142:521-3.

35. Aumiller, MS. Optic disc drusen: complications and management. Optometry. 2007;78:10–16.

36. Tekiele, BC, Semes, L. The relationship among axial length, corneal curvature, and ocular fundus changes at the posterior pole and in the peripheral retina. Optometry. 2002;73:231–236.

37. Coleman, P, Barnard, NAS. Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium: prevalence and ocular features in the optometric population. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2007;27:547–555.

38. Regillo, CD, Eagle, RC, Shields, JA, et al. Histopathologic findings in congenital grouped pigmentation of the retina. Ophthalmology. 1993;100:400–405.

39. Hurcomb P, Wolffsohn J, Napper G. Ocular signs of systemic hypertension: A review. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2001;21:430-40.

40. Saw, SM, Gazzard, G, Shih-Yen, EC, Chua, WH. Myopia and associated pathological complications. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2005;25:381–391.