Chapter 213 Vaginitis

General Considerations

General Considerations

In addition to causing physical discomfort and embarrassment, vaginitis is medically important for several reasons. It may coexist with cervicitis and may be related to a sexually transmitted infection; some of these organisms may be able to ascend and cause pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). PID may in turn lead to tubal scarring, infertility, or ectopic pregnancy. Chronic asymptomatic vaginal infections have been implicated in recurrent urinary tract infections through their action as reservoirs of the infectious agent.1,2 Some types of vaginal infections, such as bacterial vaginitis (BV) during pregnancy, are associated with preterm delivery, premature rupture of membranes, amnionitis, chorioamnionitis, and postpartum endometritis; if present at delivery, they may be associated with an increased incidence of neonatal infection, with potentially serious or fatal consequences.

The vaginal ecosystem is an environment consisting of an important relationship between normal endogenous microflora, metabolic products of the microflora and the host, estrogen, and the pH level. The normal microflora of a healthy vagina is made up of numerous microorganisms, including Candida, Lactobacillus species, gram-negative aerobic bacteria, and facultative organisms (Mycoplasma species and Gardnerella vaginalis) as well as obligate anaerobic bacteria (primarily Prevotella, Peptostreptococcus species, Eubacterium species, and Mobiluncus). Lactobacillus species dominate the healthy vagina of a reproductive-age woman, and although it is difficult to say with certainty which species are most common, molecular biology methods and at least one study have found that Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus rheuteri, and Lactobacillus acidophilus are the most often present.3 Yet another study has found that the most frequent Lactobacillius species were L. crispatus, L. gasseri, L. jensenii, and L. rhamnosus.4

The normal microflora of the vagina, dominated by lactobacilli, is capable of inhibiting the adhesion and growth of pathogens; it depletes nutrients available to pathogens and modulates the host immune response and vaginal environment.5,6 Lactobacilli act via at least three mechanisms: (1) they help to produce lactic acid and other acids as a by-product of glycogen metabolism in the vaginal vault cells and provide a normal vaginal acidic environment of 3.5 to 4.5. Many pathologic microbes cannot survive or flourish in this pH. (2) Many species of lactobacilli produce hydrogen peroxide, which also inhibits microbial growth. (3) The lactobacilli are competitive with the pathogenic microorganisms for adherence to the vaginal epithelial cells.

Types of Vaginitis

Types of Vaginitis

Vaginitis is commonly classified as being caused by yeast, bacterial vaginosis (BV), Trichomonas vaginalis, or atrophic vaginitis. However, these traditional classifications have left gaps in the proper diagnosis and treatment of several atypical scenarios of vaginitis. Experts in this field have proposed three additional categories, which include desquamative vaginitis (DIV), Mobiluncus vaginitis and lactobacillosis. Even with the addition of these three categories, there still appear to be two patterns of altered flora in symptomatic women that do not fall into any of the other designated categories. Stuart Fowler of the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona, had proposed two additional categories of altered flora: the first he describes as noninflammatory vaginitis (NV) and the second as inflammatory vaginitis (IV). With the recognition of these two patterns of altered flora, clinical presentations that do not fit the usual criteria for the diagnosis of BV, Trichomonas, Candida, atrophic vaginitis, DIV or lactobacillosis can now be recognized and treated. Details regarding these additional types of vaginitis can be found in Fowler’s published paper.7

Infectious Vaginitis

Infectious vaginitis (e.g., trichomoniasis) may be sexually transmitted or may arise from a disturbance to the delicate ecology of the healthy vagina (e.g., Candida and BV). Vaginal “infections” frequently involve common organisms found in the cervix and vagina of many healthy asymptomatic women.8

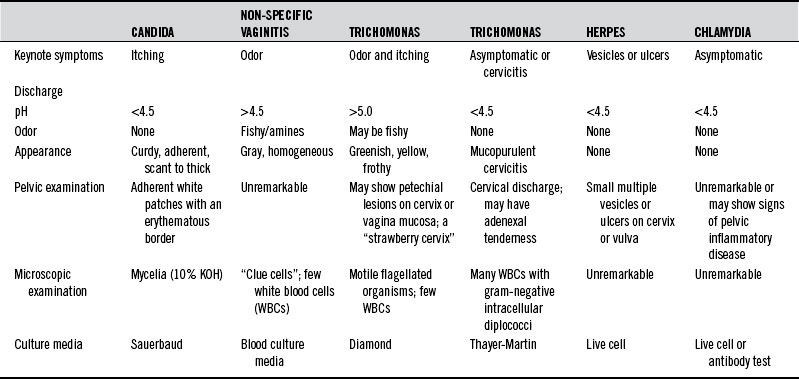

Predisposing factors for sexually transmitted infections include a higher number of sex partners, unsafe sex, birth control pills, steroids, antibiotics, tight-fitting garments, occlusive materials, douches, chlorinated pools, perfumed toilet paper, and decreased levels of lactobacilli in the vagina. Table 213-1 summarizes the diagnostic differentiation of the most common causes of infectious vaginitis.

Trichomonas vaginalis

Trichomonas vaginalis is a flagellated protozoan slightly larger than a leukocyte. It may be found in the lower urogenital tract of both men and women. Humans appear to be its only host, and sexual transmission appears to be its primary mode of dissemination. Trichomonas does not invade tissues and rarely causes serious complications. The most common symptom is leukorrhea associated with itching and burning. The discharge is frequently malodorous, greenish yellow, and frothy. The “strawberry cervix” with punctate hemorrhages is found in only a small percentage of patients with Trichomonas infection. Trichomonads grow optimally at a pH of 5.5 to 5.8.9 Thus, conditions that elevate the pH, such as increased progesterone, will favor overgrowth of Trichomonas. Conversely, a vaginal pH of 4.5 in a woman with vaginitis is suggestive of an agent other than Trichomonas. A saline wet mount of fresh vaginal fluid demonstrates the presence of small motile organisms to confirm the diagnosis in 80% to 90% of symptomatic carriers.10,11

Candida albicans

Both the relative frequency and the total incidence of candidal vaginitis have risen dramatically, 2.5-fold, in the past 20 years. This increase parallels a declining incidence of gonorrhea and trichomoniasis.12 Several factors have contributed to this increased incidence, chief among them being the greater use of antibiotics. The alterations that antibiotics make in both intestinal and vaginal ecology favor the growth of Candida. In the 1970s, Miles et al11 found a 100% correlation between genital and gastrointestinal Candida cultures, leading to the suggestion that significant intestinal colonization with Candida may be the single most significant predisposing factor in vulvovaginal candidiasis. However, this suggestion has not been confirmed by adequate research.

Steroids, oral contraceptives, and the continuing rise in incidence of diabetes mellitus all contribute to the problem. Candida is 10 to 20 times more common during pregnancy owing to the elevated vaginal pH, increased vaginal epithelial glycogen, elevated blood glucose, and intermittent glycosuria. Yeast infections are three times more prevalent in women wearing pantyhose than those wearing cotton underwear because the pantyhose prevent drying of the area.13

A woman who has four or more episodes of vulvovaginal candidiasis within 1 year is classified as having recurrent disease. Many cases of recurrent yeast infections may be caused by non-albicans strains of Candida. These resistant strains have become more problematic in recent years as women have been using more and more antifungal agents (see Box 213-1). There are three main theories to explain why women have recurring yeast vaginitis: (1) the intestinal reservoir theory, which hypothesizes that a patient’s reinoculation is due to Candida populating in the gastrointestinal tract and migrating into the vagina; (2) the sexual transmission theory, which points to the possibility that the sex partner is the source of the recurrence; and (3) the vaginal relapse theory, which maintains that some women retain small numbers of yeasts, even after treatment, that later cause a resurgence of symptoms. A considerable body of research supports this last theory.14,15 These studies include immunologic research suggesting that women with recurrent infections have an abnormal immune response to infection, which leaves them susceptible to further episodes.16

Bacterial Vaginosis

Three main factors have been identified to explain how the shift from a lactobacilli-dominant environment to one in which the anaerobes and facultative bacteria dominate and therefore why some women experience BV—sexual activity, douching, and the absence of peroxide-producing lactobacilli in the vagina. A new sex partner and frequent sexual activity are associated with an increased incidence of BV. Overall, sexual transmission of BV is not well understood. It may not be truly sexually transmitted but rather may occur by various mechanisms other than the sexual transmission of pathogens. Routine douching is associated with a loss of vaginal lactobacilli and the occurrence of BV. Women who douche regularly have BV twice as often as women who do not.17 It is possible that women with an absence of peroxide-producing lactobacilli in the vagina did not have the normal inhabitation of lactobacilli at menarche, or perhaps the lactobacilli were present but were eliminated through the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Other factors have been associated with the development of BV. Cigarette smoking is associated with BV but may be related to the downregulation of the immune response. Racial background has also been associated with BV. Hispanic women are 50% more likely to have BV, and African American women are twice as likely.18 Although the reasons for these differences are not clear, we do know that African American women practice douching twice as often as white women and that African American women are less likely to have lactobacilli in the vagina.

• Thin, dark or dull gray, homogeneous, malodorous discharge that adheres to the vaginal walls

• Positive KOH (whiff/amine) test result

• Presence of clue cells on wet mount microscopic examination

The pH is elevated to 5 to 5.5 in most cases, and there appears to be a correlation between elevated pH and the presence of odor.19

When a patient has four or more BV episodes in a year, her underlying problem is most likely an inability to re-establish a normal vaginal ecosystem with the dominant lactobacilli. There is no definition of recurrent BV, but most clinicians would probably agree that more than four episodes in a year would define the disorder. About 30% of women experience a recurrence of symptomatic BV within 1 to 3 months, and about 70% have a recurrence within 9 months.20 It is not always clear whether the recurrence represents a relapse or a reinfection. Another possibility is that a woman may be asymptomatic at times but, because of the abnormal vaginal ecosystem, she has a chronic underlying condition, so that she is sometimes symptomatic and at other times is not. Women who are asymptomatic yet have no lactobacilli are four times more likely to experience BV. Unfortunately we do not have a proved treatment for asymptomatic women.

There are potential significant consequences of altered vaginal flora in addition to susceptibility to BV. Women with BV and without sufficient lactobacilli are more susceptible to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and gonorrhea.21,22 PID is also associated with BV. There is also now good evidence that the organisms in pregnant women with BV can ascend the genital tract and cause preterm delivery, and such women are more likely to have postpartum endometritis. Women with BV are also at increased risk for infection after gynecologic surgery.

Therapeutic Considerations

Therapeutic Considerations

Dietary Considerations

The internal milieu of the vagina is a reflection of the condition of the entire body. Vaginal secretions are continuously released that affect and are affected by the microbial flora. These secretions contain water, nutrients, electrolytes, and proteins, such as secretory immunoglobulin (Ig) A. The quantity and character of these components are altered by hormonal and dietary factors. A general healthful diet is recommended in all cases to ensure the availability of all nutrients in sufficient quantity to optimize the body’s ability to respond to changing conditions. A well-balanced diet low in fats, sugars, and refined foods is particularly important in vaginitis due to infectious organisms, particularly Candida. Patients with depressed immunity are susceptible to higher rates of infection, particularly those due to Candida, Trichomonas, and herpes (see Chapter 56 for further discussion of the effects of diet on immune function).

No other food can be considered as specifically medicinal as Lactobacillus yogurt. A 1992 study investigated the effects of the daily ingestion of yogurt containing L. acidophilus on 33 women with five or more episodes per year of candidal vaginitis. Thirteen women completed the study. The women were randomized into two groups, with the first group receiving 8 oz of L. acidophilus yogurt daily for 6 months and then no yogurt for 6 months. The other group consumed the yogurt-free diet for the first 6 months and then the diet including yogurt for the second 6 months. There was a threefold reduction in infections and in candidal colonization during the yogurt diet compared with the non-yogurt diet.23

There are also studies that do not support a role for yogurt in the prevention of recurrent candidal vaginitis.24

Nutritional Supplements

Vitamin A and Beta-Carotene

Both vitamin and beta-carotene are necessary for the normal growth and integrity of epithelial tissues, such as the vaginal mucosa. Vitamin A is essential for adequate immune response and resistance to infection. Secretory IgA, a major factor in resistance to infection, is lower in vitamin A–deficient subjects.25 Beta-carotene is a source of nontoxic vitamin A precursors. In addition, it has been shown to enhance T-cell numbers and to favorably alter their ratios.26 Excessive vitamin A can be toxic and teratogenic. This is of particular concern in women of reproductive age. Total vitamin A intake should be limited to 5000 IU/day. If larger doses of vitamin A are used, patients should be cautioned to be particularly careful about contraception. Mixed carotenoids rather than synthetic beta-carotene should be used.

B Vitamins

The body requires one or more of the B vitamins for virtually every metabolic activity. B vitamins are needed for carbohydrate metabolism, protein catabolism and synthesis, cell replication, and immune function. Vitamins B2 and B6 have been shown to have estrogen-like effects and to act synergistically with estradiol. Vitamin B1 and pantothenic acid enhance the action of estradiol, although they have no estrogenic activity themselves.27 This finding suggests that B vitamins may be of use in estrogen deficiency conditions such as atrophic vaginitis, especially if combined with phytoestrogens.

Vitamin C and Bioflavonoids

Vitamin C and bioflavonoids are essential in any process related to immune function. Deficiency of vitamin C reduces the phagocytic activity of leukocytes. Both vitamin C and bioflavonoids improve connective tissue integrity, thus reducing the spread of infection. Both nutrients are also useful in diminishing the frequency and severity of herpetic outbreaks.27–32

Vaginal vitamin C has been used to treat BV. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study used a 250-mg tablet of vitamin C inserted vaginally once a day for 6 days.33 Of the 100 participants, 50 were given the active treatment and 50 placebo. At the end of the study, significantly more patients still had BV in the placebo group (35.7%) compared with the vitamin C tablet group (14%). There were no clue cells in 79% of patients receiving the vitamin C, versus 53% in the placebo group. Bacteria disappeared in 77% of the vitamin C group versus 54% in the placebo group, and lactobacilli reappeared in 79.1% of the vitamin C group versus 53.3% in the placebo group.

Vitamin E

Lack of vitamin E depresses immune response and host resistance. This situation may be corrected by high doses of supplemental vitamin E. Several experiments have shown increased resistance to chlamydial infection when subjects were supplemented with vitamin E. Vitamin E also regulates retinol in humans, and an inadequacy of vitamin E hinders the utilization of vitamin A despite adequate retinol intake.34 The use of vitamin E for the treatment of atrophic vaginitis has been reported since the 1930s.

Zinc

All DNA and RNA polymerases and repair and replication enzymes require zinc. Zinc enhances prostaglandin (PG) E1 synthesis, normalizes lymphocyte activity, and enhances epithelial growth. Low levels of zinc are associated with depressed immunity and thymic atrophy, both of which are correctable when zinc is replenished. Zinc is also essential for the proper utilization of vitamin A. Many otherwise well-nourished adults receive less than 50% of the recommended dietary allowance of zinc from their diets and have one or more measurable signs of zinc deficiency.35–37

Treatment with topical and oral zinc has been shown to reduce the duration and severity of herpes outbreaks. This may be due either to the effect of zinc on production of prostaglandins or to the direct antiviral activity of the zinc ion. High levels of zinc are also toxic to Chlamydia and Trichomonas and have been used successfully in vaginitis that did not respond to antibiotic therapy.38–42

Botanical Medicines

Glycyrrhiza glabra

Licorice (G. glabra) has antiviral activity against RNA and DNA viruses and has been used successfully in the treatment of herpes. The number and severity of recurrences may be reduced by the repeated application of licorice gel to active lesions.43 18-beta glycyrrhetinic acid has been shown in vitro to be effective against Candida.44 (For further discussion, see Chapter 96.)

Chlorophyll

Chlorophyll has bacteriostatic action and soothing actions. Water-soluble chlorophyll may be added to douching solutions for symptomatic relief of vaginitis.45–47

Allium sativum

Garlic (A. sativum)—which is antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal—has been shown to be effective even against some antibiotic-resistant organisms.48–52 The major growth-inhibitory component in garlic extract is allicin; therefore, garlic products with the highest amount of allicin are preferable. Garlic cloves may be carefully peeled so as not to nick them and then pierced with thread and used as tampons. A garlic capsule may also be inserted into the vagina.

Hydrastis canadensis and Berberis vulgaris

Goldenseal (H. canadensis) and Oregon grape (B. vulgaris) contain berberine, which has a significant effect against many bacteria. Berberine enhances immune function when taken internally as a tea and offers symptomatic local relief when used in douching solutions because it is soothing to inflamed mucous membranes.53–56 (For further discussion, see Chapter 97).

Melaleuca alternifolia

An alcoholic extract of the oil of the tea tree (M. alternifolia), diluted to 1% in water, exerts a strong antibacterial and antifungal action. It was shown in one study to be effective in treating trichomoniasis, candidiasis, and cervicitis. Treatment consists of daily douching combined with saturated tampons used weekly. No adverse reactions were reported, and patients commented favorably on its soothing effect57 (for further discussion, see Chapter 102). Various tea tree oil preparations have demonstrated antimicrobial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and C. albicans.58

Botanical Mixture

Women with abnormal vaginal discharge who presented to a gynecologic clinic in India were randomly assigned to receive either a cream containing Azadirachta indica (neem) seed oil, Sapindus mukerossi (reetha) saponin extract, and quinine or placebo. They applied the cream intravaginally at bedtime for 14 days. The results were quite impressive. Symptomatic and microbial assessment showed that 10 of 12 women with C. trachomatis vaginitis recovered within 1 week, and 10 of 17 with BV recovered within 2 weeks. No benefit was found in women with candidal or trichomonal infections, and none of the women using the placebo recovered from any of the infections.59

Other Agents

Lactobacillus Species

Lactobacilli are the dominant organisms in the vagina of a healthy reproductive-aged premenopausal woman. Properties of these strains—including their adhesiveness, ability to produce acids and hydrogen peroxide, and production of bacteriocidins and biosurfactants—confer protection on the host. Selection of Lactobacillus species and strains for therapeutic purposes with these properties should be a guiding principle for their use in treatment. Substantial data have been published on a number of strains, their properties, and their ability to fight pathogens. Many species and specific strains have demonstrated antipathogenic activity; these include L. rhamnosus GG, L. acidophilus NCFM, L. casei Shirota, L. reuteri MM-53, L. casei CRL-431, L. rhamnosus GR-1, L. fermentum RC-14 (now called L. rheuteri), L. plantarum 299V, and L. salivarius.60 Other Lactobacillus strains, such as L. johnsonii LC1, L. plantarum 299V, and L. crispatus CTV05 also have excellent potential owing to their ability to colonize the vagina and produce hydrogen peroxide, although more data are needed.

Several studies have supported the use of Lactobacillus in the prevention and treatment of vaginitis. One study on treating BV found that both vaginal administration and oral-plus-vaginal administration of lactobacilli were effective at reducing the vaginal pH, treating the current infection, and preventing recurrence over the subsequent 3 months.61 Another study examined the effectiveness of weekly intravaginal L. acidophilus versus clotrimazole (antifungal) tablets in HIV-positive women, a group highly susceptible to recurrent yeast vaginitis, and found the two treatments to be similarly effective at preventing candidiasis.62 After any conventional treatment with antibiotics, vaginal lactobacilli can be restored by the coadministration of Lactobacillus and low-dose vaginal estriol.63 Another randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial of BV was conducted with 100 women who were given a 2% vaginal clindamycin cream for 7 days and then randomized to receive vaginal capsules for 10 days containing either a placebo or a combination of L. gasseri and L. rhamnosus (10 billion colony forming units/capsule); this was then repeated for 3 cycles. The probiotics did not improve efficacy of BV treatment during the first month of treatment. However, women initially “cured” were followed for 6 menstrual cycles or until relapse within that time. At the end of 6 months, 64.9% of the probiotic-treated group were still BV-free compared with 46.2% in the placebo group.85

Another study enrolled 125 premenopausal women diagnosed with BV by presence of vaginal irritation, discharge and ‘fishy’ odor, and Nugent criteria and detection of sialidase enzyme. The subjects were treated with oral metronidazole (500 mg) twice daily from days 1 to 7, and randomized to receive oral Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 (1 × 10[9]) and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14 (1 ×10[9]) or placebo twice daily from days 1 to 30. Primary outcome was cure of BV as determined by normal Nugent score, negative sialidase test, and no symptoms or signs of BV at day 30. A total of 106 subjects returned for 30-day follow-up, of which 88% were cured in the antibiotic/probiotic group compared with 40% in the antibiotic/placebo group (P <0.001). Of the remaining subjects, 30% subjects in the placebo group and none in the probiotic group had BV, while 30% in the placebo and 12% in the probiotic group fell into the intermediate category based upon Nugent score, sialidase result and clinical findings. High counts of Lactobacillus sp. (>10[5] CFU/mL) were recovered from the vagina of 96% probiotic-treated subjects compared with 53% controls at day 30. In summary, this study showed efficacious use of lactobacilli and antibiotic in the eradication of BV in black African women.86

There are more studies showing these specific species in the treatment of BV. In another clinical trial, 64 premenopausal women with diagnosed BV received a single dose of tinidazole (2 g) and either one capsule of L. rhamnosus GR-1 (1 × 10[9]) and L. reuteri RC-14 (1 × 10[9]) or placebo orally, twice a day, from days 1 to 28. At day 28, the probiotic group had a higher cure rate (Nugent score and Amsel test) of BV compared with placebo (87.5% vs 50%; P = 0.001). According to the Gram-stain Nugent score, more women in the probiotic group were assessed with “normal” vaginal microbiota compared with placebo (75% vs 34.4%; p = 0.011).87

Another way to use these probiotic species is after conventional treatment. In one clinical trial, 95 women (39 with BV, 45 with VVC and 11 had both infections) were randomized to receive a vaginal capsule containing L. gasseri LN40, L. fermentum LN99, L. casei rhamnosus LN113, P. acidilactici LN23 (10[8]-10[10] cfu) or placebo for 5 days following conventional treatment. Probiotic strains were present in vaginal cultures 2 to 3 days after administration (53% colonized after one menstruation). Ninety-three percent of women in the probiotic group were cured after 2 to 3 days compared with 83% in the placebo group (78% vs 71% after first menstruation).The probiotic group also had significantly less malodorous discharge.88

A clinical trial for vulvovaginal candidiasis employed Lactobacillus GG suppositories which were given twice a day for 7 days to women with more than 5 infections per year.64 Four of the five women with positive yeast cultures had negative cultures after receiving this treatment. All the women reported improvement of their vaginal symptoms of erythema and discharge.

Another study examined the ability of intravaginal Lactobacillus to reduce the risk of VVC in 164 HIV-positive women.65 These women were randomized into three groups with one group receiving L. acidophilus intravaginally once a week. The second group received vaginal clotrimazole weekly, and the third group received a placebo. During the 21-month study, the relative risk of developing VVC was 0.5 for the lactobacilli group and 0.4 for the prescription antifungal group compared with placebo. In addition, women who used the lactobacilli went for a longer period of time until they became infected compared with the women who received a placebo.

Other studies have demonstrated that when lactobacilli are given orally, they do colonize the vagina and/or reduce vaginal candidal infections. Three studies, all using L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. fermentum RC-14, have been positive and showed a significant reduction in yeast66 or reduction in the recurrences of yeast vaginitis67 or restoration of normal vaginal flora in women with a history of VVC.68

A review of Lactobacillus treatments for VVC in 200369 found that vaginally administered or orally ingested Lactobacillus is able to colonize the vaginal ecosystem and that supplementation generally had to continue 2 to 6 months in order to sustain continued colonization. The author also concluded that controlled trials are encouraging but few, and that these trials had small numbers of participants, inadequate controls or lack of blinding, high attrition rates, and were not consistent in the form of Lactobacillus used. In addition, they produced conflicting results.

There are a few studies that do not support a role for probiotics in the prevention of recurrent VVC or BV.24,70

Iodine

Iodine used topically is effective against a wide range of organisms, including Trichomonas, Candida, Chlamydia, and nonspecific vaginitis. Povidone-iodine (Betadine) has all the advantages of iodine without the disadvantages of stinging and staining. A study published in 1969 found povidone-iodine to be effective in treating 100% of cases of candidal vaginitis, 80% of cases due to Trichomonas, and 93% of combination infections. Although douching has not been as strongly recommended, this study found a douching solution diluted to 1 part iodine in 100 parts water (e.g., 1.5 to 3 teaspoons povidone-iodine to 1 quart of water) used twice daily for 14 days to be effective against most organisms.69,71–78

Boric Acid

Vaginal capsules of boric acid have been shown to treat candidiasis with success rates equal to or better than those for nystatin. In the most impressive study, 100 women with chronic resistant yeast vaginitis for whom extensive and prolonged conventional therapy had failed were treated with vaginal suppositories containing 600 mg of boric acid twice a day for 2 or 4 weeks. This regimen was effective in curing 98% of the women with failure of response to the most commonly used antifungal agents,78 thus offering an inexpensive, easily accessible therapy for vaginal yeast infections.79,80

A recent review of boric acid for recurrent candida vaginitis sheds some light on its effectiveness.89 Fourteen studies, including two randomized clinical trials, nine case series, and four case reports were included in this review of the clinical evidence utilizing intravaginal boric acid for vulvovaginal candidiasis. Boric acid was compared with nystatin, gterconazole, flucytosine, itraconazole, clotrimazole, ketoconazole, fluconazole, buconazole, and miconazole. The mycologic and clinical cure rates were as follows:

Kudzu (Pueraria mirifica)

P. mirifica was examined for its effect on vaginal symptoms, vaginal health index, vaginal pH, and vaginal cytology in postmenopausal women.81 In this randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study, the participants were given either 20, 30, or 50 mg of P. mirifica in capsule or placebo daily for 24 weeks. The average vaginal dryness symptoms in the treatment group decreased after 12 weeks and the maturation index increased after 24 weeks. This effect is evidence of an estrogenic effect on vaginal tissue due to this plant and points to its clinical use for vaginal dryness and dyspareunia due to vaginal atrophy.

Hops

A study was conducted using a combination gel containing phytoestrogens from hops extract, hyaluronic acid, liposomes, and vitamin E.82 This open noncontrolled trial was performed on 150 postemenopausal women presenting with vaginal dryness and related symptoms. One vaginal suppository per day was inserted for the first 14 days and then one suppository every other day for 14 days. The primary endpoint was the evaluation of vaginal dryness by both the patient and the investigator. The secondary endpoints were the evaluation of other symptoms, including vaginal itching, burning, dyspareunia, inflammation, swelling or irritation, or vulvovaginal abrasions. Among the 130 women who completed the study, the average vaginal dryness scale decreased from 7.92 to 0 by the end of the treatment. Itching disappeared progressively throughout the treatment period and only 4 women still had itching at the end of the treatment. Burning was severe in 92 women at baseline, moderate in 26 and mild in 11. By the end of the treatment, only 4 women complained of mild burning. Dyspareunia also improved progressively; by the end, only 5 women of the 130 who reported mild to moderate or severe dyspareunia had mild dyspareunia. Inflammation and irritation of vulvar and vaginal mucosa also improved significantly from the beginning to the end of the treatment period.

Vaginal DHEA

A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the effect of daily local intravaginal DHEA ovules for 12 weeks in postmenopausal women. The main assessment criteria were sexual dysfunction parameters of libido, arousal, orgasm, and dyspareunia in postmenopausal women with vaginal atrophy.83 A total of 218 postmenopausal women were randomized to receive a daily ovule of either no DHEA, 3.25 mg DHEA, 6.5 mg DHEA, or 13 mg DHEA. The ovules contained Prasterone, in a lipophilic agent manufactured by Recipharm of Sweden. At 12 weeks, compared with placebo, the 13-mg ovule improved symptoms by 68% in the abbreviated sex function/arousal/sensation domain, in the arousal/lubrication domain by 39%, orgasm by 75%, and dryness during intercourse by 57%. DHEA also fared better than placebo in the desire domain of menopause-specific quality of life inventory by 49% to 23%.

In a related study by the same authors, serum levels of vaginal DHEA showed no or minimal changes during the study period, which lasted up to 12 weeks. All values remained within the normal range of postmenopausal women.84 This bodes well for safety issues.

Diagnostic Approach

Diagnostic Approach

Some women are hesitant to mention symptoms of vaginitis to their doctors out of embarrassment, associating them with poor personal hygiene or promiscuity. Because of the relative frequency of occurrence of vaginitis and the potential for serious consequences if it is untreated, all female patients should be questioned directly regarding the presence of pruritus, vaginal discharge, dysuria, or other symptoms of vaginitis. The following protocol outlines the basic approach to diagnosis:

1. Obtain a complete gynecologic and sexual history, including details of the sexual activity and practices of the patient and her partner or partners. Determine method of contraception, personal hygiene habits, and any self-medications. Rule out the presence of associated symptoms suggestive of PID or systemic infection. Inquire about previous occurrences and their diagnosis, treatment, and resolution.

2. Identification of the causative agent is essential for successful treatment and evaluation. To facilitate diagnosis, the patient should be instructed to avoid douching, intercourse, and vaginal medications for 1 to 2 days prior to the office visit.

3. Determine by speculum examination whether the discharge emanates from the vagina or the cervix. Note the condition of the vaginal mucosa and the character of any discharge. Specimens should be collected and then placed on slides for saline and KOH examination. Use pH paper, amines testing strips, and microscopy of wet mounts.

5. Use microscopy when needed for diagnosis (e.g., KOH wet prep).

6. Appropriate culture specimens should be taken if the diagnosis remains in question or if screening for gonococcus or Chlamydia is desired (highly recommended). An abdominal/bimanual examination should be done. A genital culture can be used to diagnose beta strep, yeast, BV (not well), Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli. A yeast culture can be ordered and a request to identify different strains of Candida can be made. A Group B strep DNA probe or group B strep culture should be ordered for pregnant patients.

7. The Affirm VP III test is used to diagnose Candida species, BV, and trichomoniasis.

8. The Thin prep can actually test for many different pathogens including the detection and identification of human papillomavirus and its genotype, HPV 16/18, Chlamydia, gonococcus, Trichomonas, yeast, Actinomyces, herpesviruses I and II, Group B strep, BV, syphilis, Ureaplasma, and Mycoplasma.

Therapeutic Approach

Therapeutic Approach

Because approximately 90% of all cases of vaginitis are due to Candida, Trichomonas, or Gardnerella infections, the following recommendations are primarily directed to treatment of these organisms. Owing to the infectious nature of these organisms, immune support (through proper diet, nutritional supplementation, and botanical medicines) is an important aspect of the therapy. For further recommendations on treating atrophic vaginitis, see Chapter 188; for herpes simplex, see Chapter 172.

Supplements

General Recommendations

1. In treating infectious vaginitis, the following natural medicine concepts should be kept in mind:

2. In all cases of chronic vaginitis, Lactobacillus capsules or Lactobacillus yogurt should be used daily, at least orally if not vaginally, to reinoculate the vagina with these desirable organisms. Oral use should continue for 2 to 6 months to assure colonization.

3. Treatment failures may be due to incorrect diagnosis, reinfection, failure to treat predisposing factors, or patient resistance to the treatment used.

4. Trichomonas infections in women require concurrent treatment of the male partner.

5. In cases of recurrent or chronic BV or yeast vaginitis, the clinician should consider treating both male and female partners, infection in whom is a possible explanation for recurrent disease.

Specific Recommendations/Sample Treatments

Chronic candida vaginitis

• 8 oz of Acidophilus yogurt every day

• L. species (e.g., rhamnosus, rheuteri) 1-5 billion; twice daily for 1 to 6 months

• Boric acid: 600 mg vaginal suppositories twice a day for 2 weeks (4 weeks if patient is not free of symptoms and wet mount examination still shows organisms at 2 weeks)

• To prevent vulvar irritation from the boric acid dispensed from the dissolved capsule, vitamin E oil or petroleum jelly can be applied to the external genitalia.

1. Stamey T. The role of introital enterobacteria in recurrent urinary infections. J Urol. 1973;109:467–472.

2. Netto N.R., Rangel P., DaSilva R., et al. The importance of vaginal infection on recurrent cystitis in women. Int Surg. 1979;64:79–82.

3. McGroarty J. Probiotic use of lactobacilli in the human female urogenital tract. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;6:251–264.

4. Kiss H., Kogler B., Petricevic L., et al. Lactobacillus microbiota of healthy women in the late first trimester of pregnancy. BJOG. 2007;114:1402–1407.

5. Erickson K., Hubbard N. Probiotic immunomodulation in health and disease. J Nutr. 2000;130(suppl 25):S403–S409.

6. Reid G., Cook R., Bruce A. Examination of strains of lactobacilli for properties that may influence bacterial interference in the urinary tract. J Urol. 1987;138:330–335.

7. Fowler S. Expansion of altered vaginal flora states in vaginitis to include a spectrum of microflora. J Reproductive Medicine. 2007;52(2):93–99.

8. Larsen B., Galask R. Vaginal microbial flora: practical and theoretic relevance. Ob Gyn. 1980;55:S100–S113.

9. Hildebrandt R.J. Trichomoniasis: always with us—but controllable. Med Times. 1978;106:44–48.

10. Sparling P.F. Introduction to sexually transmitted diseases and common syndromes. In: Bennett J.C., Plum F. Cecil textbook of medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996:1669–1700.

11. Miles M.R., Olsen L., Rogers A., et al. Recurrent vaginal candidiasis: importance of an intestinal reservoir. JAMA. 1977;238:1836–1837.

12. Meeker C.I. Candidiasis: an obstinate problem. Med Times. 1978;106:26–32.

13. Heidrich F., Berg A., Gergman F., et al. Clothing factors and vaginitis. J Fam Pract. 1984;19:491–494.

14. O’Connor M., Sobel J. Epidemiology of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: identification and strain differentiation of Candida albicans. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:358–363.

15. Mercure S., Poirier S., Lemay G., et al. Application of biotyping and DNA typing of Candida albicans to the epidemiology of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:502–507.

16. Fidel P., Sobel J. Immunopathogenesis of recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:335–348.

17. Hawes S., Hillier S., Benedetti J., et al. Hydrogen-peroxide-producing lactobacilli and acquisition of vaginal infections. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1058–1063.

18. Goldenberg R., Klebanoff M., Nugent R., et al. Bacterial colonization of the vagina during pregnancy in four ethnic groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1618–1624.

19. Fleury F.J. Is there a “non-specific” vaginitis? Med Times. 1978;106:37–43.

20. Blackwell A., Fox A., Phillips I., et al. Anaerobic vaginosis (nonspecific vaginitis): clinical, microbiological, and therapeutic findings. Lancet. 1983;2:1379–1382.

21. Martin J., Richardson B., Nyange P., et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1863–1868.

22. Taha T., Hoover D., Dallabeta G., et al. Bacterial vaginosis and disturbances of vaginal flora: association with an increased acquisition of HIV. AIDS. 1998;12:1699–1706.

23. Hilton E., Isenberg H., Alperstein P., et al. Ingestion of yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus as prophylaxis for candidal vaginitis. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116:353–357.

24. Shaley E., Battino S., Weiner E., et al. Ingestion of yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus compared with pasteurized yogurt as prophylaxis for recurrent candidal vaginitis and bacterial vaginosis. Arch Fam Med. 1996;5:593–596.

25. Sirisnha S., Daziy M., Moongkarndi P., et al. Impaired local immune response in vitamin A deficient rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 1980;40:127–135.

26. Alexander M.M., Newmark H., Miller R. Oral betacarotene can increase the number of OKT4? cells in human blood. Immunol Letters. 1985;9:221–224.

27. Sharaf A., Gomaa N. Interrelationship between vitamins of the B-complex group and oestradiol. J Endo. 1974;62:241–244.

28. Beisel W.R., Edelman R., Nauss K., et al. Single-nutrient effects on immunologic functions. JAMA. 1981;245:53–58.

29. Stankova L., Gerhardt N., Nagel L., et al. Ascorbate and phagocyte function. Infect Immun. 1975;12:252–256.

30. Havsteen B. Flavonoids, a class of natural products of high pharmacological potency. Biochem Pharm. 1983;32:1141–1148.

31. Holden M., Resnick R. The in-vitro action of synthetic crystalline vitamin C (ascorbic acid) on Herpes virus. J Immunol. 1936;31:455–462.

32. Terezhalmy G., Bottomley W., Pelley G. The use of water soluble bioflavonoid-ascorbic acid complex in the treatment of recurrent herpes labialis. Oral Surg. 1978;45:60–62.

33. Petersen E., Magnani P. Efficacy and safety of vitamin C vaginal tablets in the treatment of non-specific vaginitis. European J Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2004;117(1):70–75.

34. Stephens L., McChesney A., Nockels C. Improved recovery of vitamin E treated lambs that have been experimentally infected with intertracheal Chlamydia. Br Vet J. 1979;135:291–293.

35. Pories W., Henzel J., Rob C., et al. Acceleration of wound healing in man with zinc sulphate given by mouth. Lancet. 1967;1:121–124.

36. Sandstead H., Lanier V., Jr., Shepard G., et al. Zinc and wound healing. Am J Clin Nutr. 1970;23:514–519.

37. Liszewski R. The effect of zinc on wound healing: a collective review. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1981;81:104–106.

38. Greenberg S., Harris D., Giles P., et al. Inhibition of Chlamydia trachomatis growth by zinc. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;27:953–957.

39. Krieger J., Rein M. Zinc sensitivity of Trichomonas vaginalis: in vitro studies and clinical implications. J Infect Dis. 1982;146:341–345.

40. Willmott F., Say J., Downey D., et al. Zinc and recalcitrant trichomoniasis [letter]. Lancet. 1983;1:1053.

41. Tennican P., Carl G., Frey J., et al. Topical zinc in the treatment of mice infected intravaginally with Herpes genitalis virus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1980;164:593–597.

42. Gordon Y., Asher Y., Becker Y. Irreversible inhibition of herpes simplex virus replication in BSC-cells by zinc ions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1975;8:377–380.

43. Mitchell W. Naturopathic applications of the botanical remedies. Seattle, WA: JBC Publications; 1983.

44. Pellati D., Fiore C., Armanini D., et al. In vitro effects of glycyrrhetinic acid on the growth of clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Phytother Res. 2009 Apr;23(4):572–574.

45. Mowbray S. The antibacterial activity of chlorophyll. Br Med J. 1957;1:268–270.

46. Goldberg S. The use of water soluble chlorophyll in oral sepsis. Am J Surg. 1943;62:117–122.

47. Smith L., Livingston A. Chlorophyll: an experimental study of its water soluble derivatives in wound healing. Am J Surg. 1943;62:358–369.

48. Sharma V., Sethi M.S., Kumar V., et al. Antibacterial property of Allium sativum Linn. in vivo and in vitro studies. Ind J Exp Bio. 1977;15:466–468.

49. Moore G., Atkins R. The fungicidal and fungistatic effects of an aqueous garlic extract on medically important yeast-like fungi. Mycologia. 1977;69:341–348.

50. Cavallito C., Bailey J. Allicin, the antibacterial principle of Allium sativum. I. Isolation, physical properties and antibacterial action. J Am Chem Soc. 1944;66:1950–1951.

51. Barone F., Tansey M. Isolation, purification, identification, synthesis, and kinetics of activity of the anticandidal component of Allium sativum, and a hypothesis for its mode of action. Mycologia. 1977;69:793–825.

52. Prat M. Algunas consideraciones sobre la accion antibiotica del Allium sativum y sus preparados [trans]. Biol Abstr. 1950;24:264.

53. Hahn F., Ciak J. Berberine. Antibiotics. 1976;3:577–588.

54. Sabir M., Bhide N. Study of some pharmacological actions of berberine. Ind J Phys Pharm. 1971;15:111–132.

55. Sabir M., Mahajan V., Mohaptra L., et al. Experimental study of the antitrachoma action of berberine. Ind J Med Res. 1976;64:1160–1167.

56. Dutta N., Panse M. Usefulness of berberine (an alkaloid from Berberis aristata) in the treatment of cholera (experimental). Ind J Med Res. 1962;50:732–735.

57. Pena E.F. Melaleuca alternifolia oil. Its use for trichomonal vaginitis and other vaginal infections. Ob Gyn. 1962;19:793–795.

58. Williams L., Home V. A comparative study of some essential oils for potential use in topical applications for the treatment of the yeast Candida albicans. Aust J Med Herbal. 1995;7:57–62.

59. Mittal A., Kapur S., Garg S., et al. Clinical trial with Praneem polyherbal cream in patients with abnormal vaginal discharge due to microbial infections. Aust N Z J Obstet Gyn. 1995;35:190–191.

60. Reid G. Thes scientific basis for probiotic strains of Lactobacillus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3763–3766.

61. Delia A., Morgante G., Rago G., et al. Effectiveness of oral administration of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei F19 in association with vaginal suppositories of Lactobacillus acidofilus in the treatment of vaginosis and in the prevention of recurrent vaginitis. Minerva Ginecol. 2006 Jun;58(3):227–231.

62. Williams A.B., Yu C., Tashima K., et al. Evaluation of two self-care treatments for prevention of vaginal candidiasis in women with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2001 Jul-Aug;12(4):51–57.

63. Ozkinay E., Terek M.C., Yayci M., et al. The effectiveness of live lactobacilli in combination with low dose oestriol (Gynoflor) to restore the vaginal flora after treatment of vaginal infections. BJOG. 2005 Feb;112(2):234–240.

64. Hilton E., Rindos P., Isenberg H. Lactobacillus GG vaginal suppositories and vaginitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1433.

65. Williams A., Yu C., Tashima K., et al. Evaluation of two self care treatments for prevention of vaginal candidiasis in women with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2001;12:51–57.

66. Reid G., Charbonneau D., ERb J., et al. Oral use of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR01 and L. fermentum RC-14 significantly alters vaginal flora: randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 64 healthy women. FEMS Immun Med Microbiol. 2003;35:131–134.

67. Reid G., Bruce A., Fraser N., et al. Oral probiotics can resolve urogenital infections. FEMS Immun Med Microbiol. 2001;30:49–52.

68. Reid G., Beueman D., Heinemann C., et al. Probiotic Lactobacillus dose required to restore and maintain a normal vaginal flora. FEMS Immu Med Microbiol. 2001;32:37–41.

69. Gershenfeld L. Povidone iodine as a vaginal microbicide. Am J Pharm. 1962;134:278–291.

70. Pirotta M., Gunn J., Chondros P., et al. Effect of lactobacillus in preventing post-antibiotic vulvovaginal candidiasis: a randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;329:548–552.

71. Shook D. A clinical study of a povidone-iodine regimen for resistant vaginitis. Curr Ther Res. 1963;5:256–263.

72. Maneksha S. Comparison of povidone-iodine (Betadine) vaginal pessaries and lactic acid pessaries in the treatment of vaginitis. J Int Med Res. 1974;2:236–239.

73. Reeve P. The inactivation of Chlamydia trachomatis by povidone iodine. J Antimicrob Chemo. 1976;2:77–80.

74. Ratzen J. Monilial and trichomonal vaginitis: topical treatment with povidone iodine treatments. Cal Med. 1969;110:24–27.

75. Mayhew S. Vaginitis. A study of the efficacy of povidone iodine in unselected cases. J Int Med Res. 1981;9:157–159.

76. Gershenfeld L. Povidone iodine as a trichomoniacide. Am J Pharm. 1962;134:324–331.

77. Singha H. The use of a vaginal cleansing kit in non-specific vaginitis. Practitioner. 1979;223:403–404.

78. Jovanovic R., Congema E., Nguyen H. Antifungal agents vs boric acid for treating chronic mycotic vulvovaginitis. J Reprod Med. 1991;36:593–597.

79. Swate T., Weed J. Boric acid treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis. Ob Gyn. 1974;43:894–895.

80. Keller Van Slyke K. Treatment of vulvovaginal candidiasis with boric acid powder. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1981;141:145–148.

81. Manonai J., Chittacharoen A., Theppisai U., et al. Effect of Pueraria mirifica on vaginal health. Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society. 2007;14(5):919–924.

82. Costantino D., Guaraldi C. Effectiveness and safety of vaginal suppositories for the treatment of the vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: an open, non-controlled clinical trial. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences. 2008;12:411–416.

83. Labrie F., Archer D., Bouchard C., et al. Effect of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (Prasterone) on libido and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2009;16:923–931.

84. Labrie F., Archer D., Bouchard C., et al. Serum steroid levels during 12-week intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone administration. Menopause. 2009;16(5):897–906.

85. Larrsson P., Stray-Pedersen B., Ryttig K., et al. Human lactobacilli as supplementation of clindamycin to patients with bacterial vaginosis reduce the recurrence rate: a 6-month, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. BMC Women’s Health. 2008;8:3.

86. Anukam K., Osazuwa E., Ahonkhai I., et al. Augmentation of antimicrobial metronidazole therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1450–1454.

87. Martinez R., Franceschini S., Patta M., et al. Improved cure of bacterial vaginosis with single dose of tinidazole (2 g), Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1, and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Can J Microbiol. 2009;55:133–138.

88. Ehrström S., Daroczy K., Rylander E., et al. Lactic acid bacteria colonization and clinical outcome after probiotic supplementation in conventionally treated bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis. Microbes Infect. 2010 Sep;12(10):691–699.

89. Iavazzo C., Gkegkes I., Zarkada I., et al. Boric acid for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis: the clinical evidence. J Women’s Health. 2011;20(8):1245–1255.