Vaginal Repair of Vesicovaginal Fistula

Surgical treatment of benign pelvic conditions causes approximately 90% of vesicovaginal fistulas, with total abdominal hysterectomy being the most common cause. The point at which the fistula first becomes symptomatic is determined to a major degree by its cause, its site of origin, and the method of catheter drainage. Immediate postoperative leakage probably represents an unrecognized perforation or laceration somewhere in the lower urinary tract. Many fistulas occur secondary to trauma, crushing injuries from clamps, or suture penetration into the lower urinary tract, which may result in devascularization, necrosis, and invariably fistulous development between the second and tenth postoperative days.

If a vesicovaginal fistula is diagnosed within 7 days of occurrence, is less than 1 cm in diameter, and is unrelated to malignancy or irradiation, bladder drainage alone for up to 4 weeks allows spontaneous healing in 12% to 80% of cases; however, the outcome is very unpredictable. Cystoscopic cauterization of small lesions may also be successful. Standard management of the vesicovaginal fistula dictates an interval from injury to repair of 3 to 6 months in surgical and obstetric fistulas, and up to 1 year in irradiation-induced fistulas, to ensure complete resolution of necrosis and inflammation. However, recently, some have championed the early closure of small fistulas with good results.

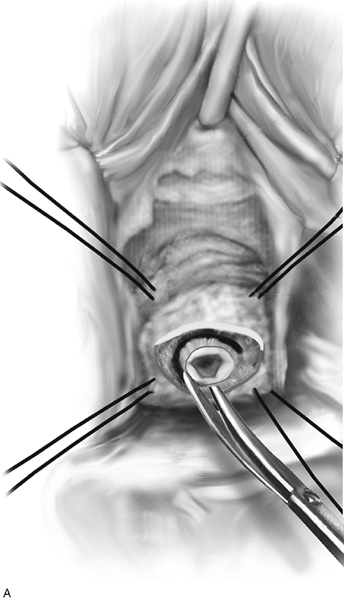

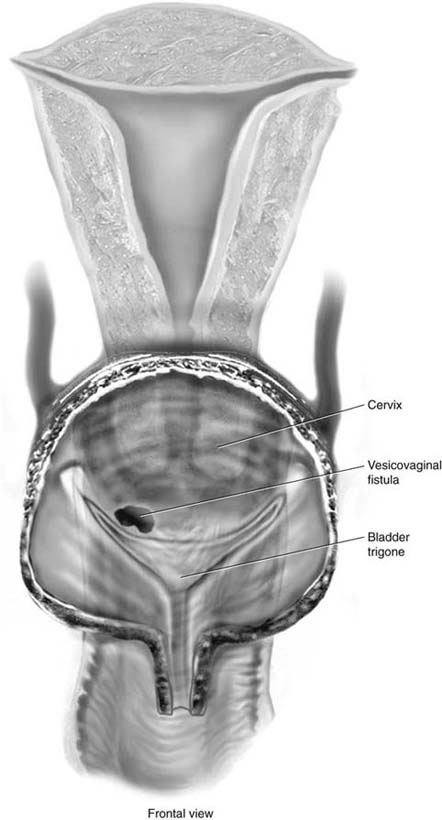

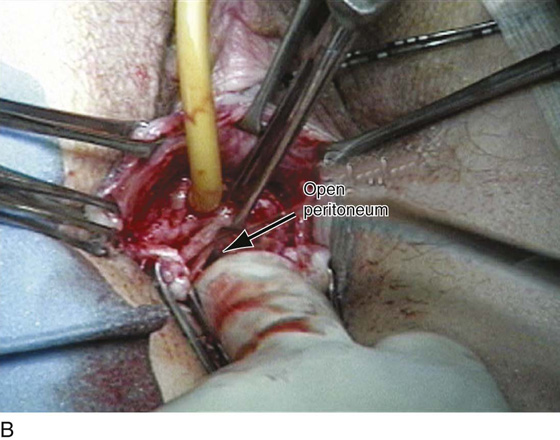

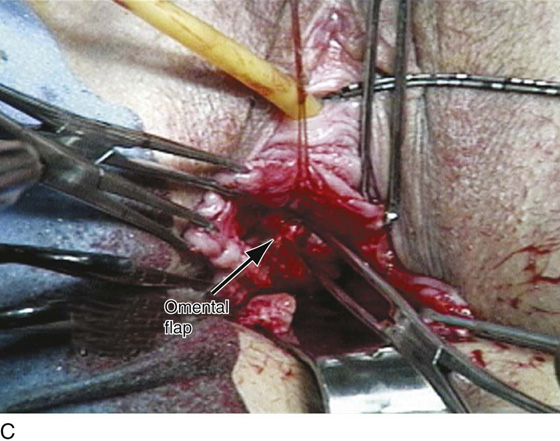

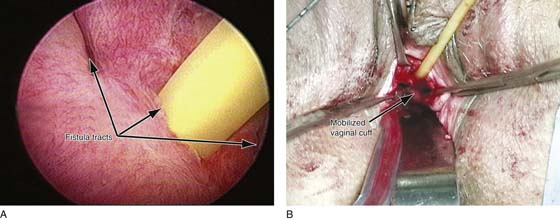

Most vesicovaginal fistulas can be closed transvaginally. Simple vesicovaginal fistulas are usually repaired with the Latzko technique (Fig. 90–1), whereas more complex procedures usually require excision of the tract and a layered closure of the defect (Fig. 90–2). If the fistula encroaches on one or both ureteral orifices (Fig. 90–3), the ureters should be catheterized at the onset of surgery. Intraoperative placement of a pediatric Foley catheter through the fistula and into the bladder helps to evert the fistula edge, thus improving descent and stability for dissection (Fig. 90–4).

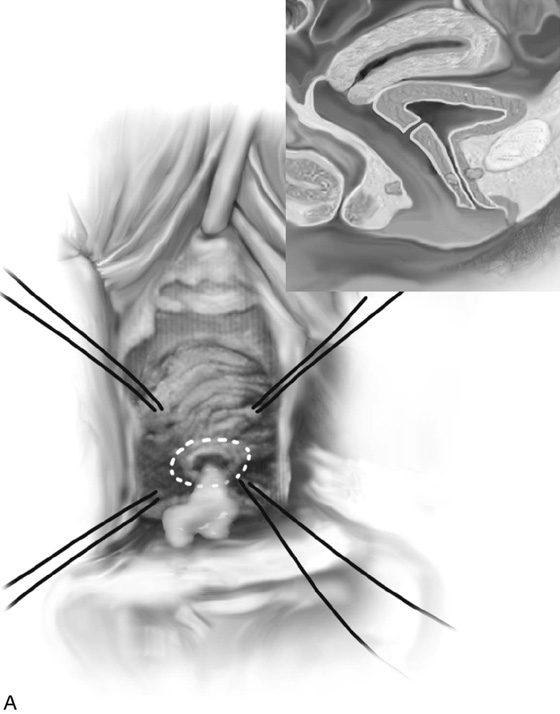

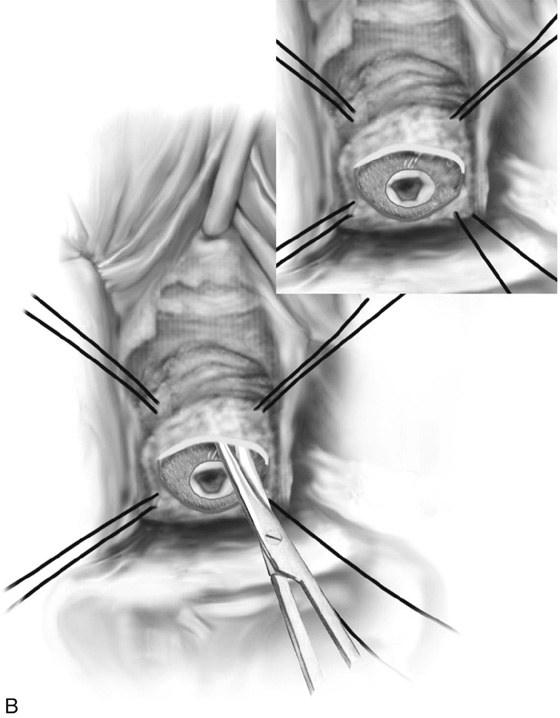

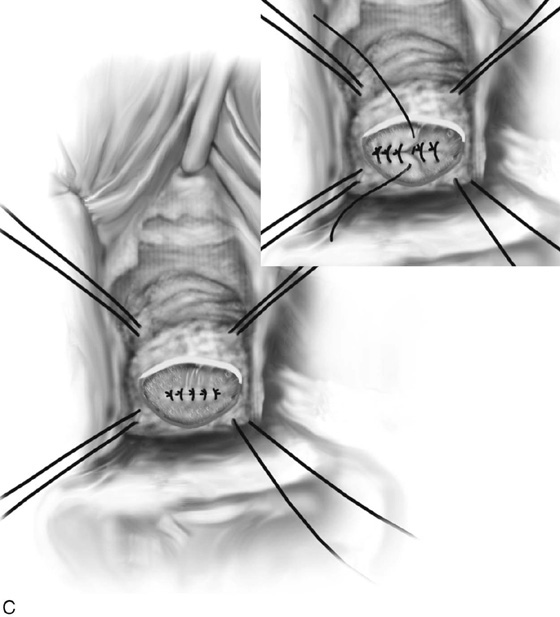

The Latzko technique of partial colpocleisis may be used for repair of posthysterectomy vesicovaginal fistulas, with reported cure rates of between 93% and 100% after the first attempt. As a simple procedure, it offers the advantages of a short operating time, minimal blood loss, and low postoperative morbidity. Inadequate vaginal length is not a problem unless the vagina is already shortened. In the Latzko operation, the vaginal mucosa is mobilized around the fistula margin in the shape of an ellipse for at least 2.5 cm in all directions, with closure of the subvaginal tissue and vaginal mucosa in layers using 2-0 or 3-0 interrupted absorbable sutures (see Fig. 90–1). The vaginal wall in contact with the bladder reepithelializes transitional epithelium.

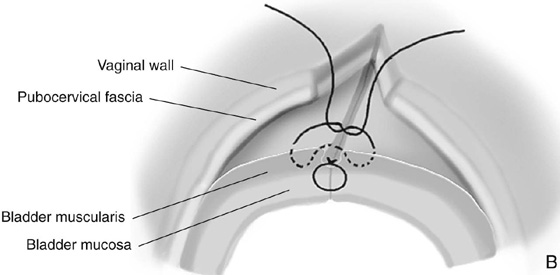

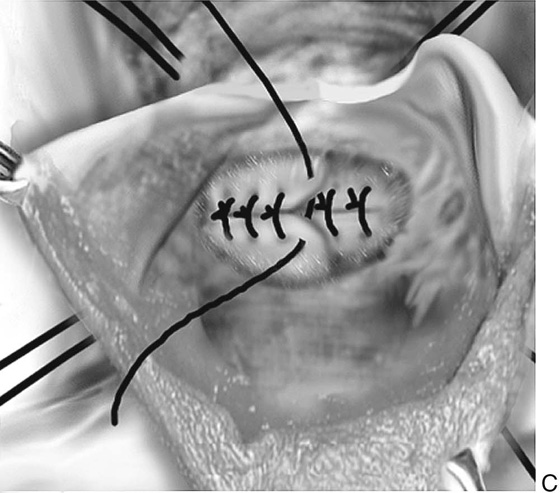

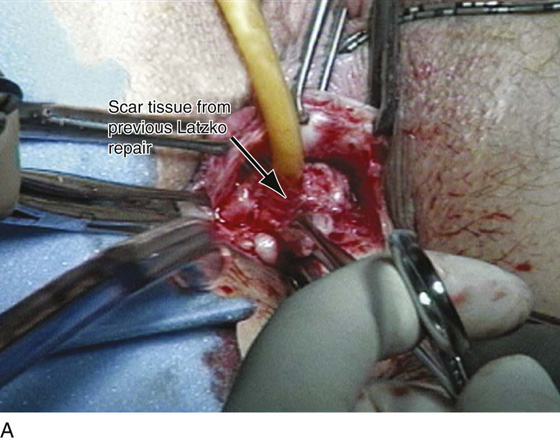

For complicated or larger fistulas, a classic technique is best. This involves circumscribing the vaginal mucosa in the region of the fistula (see Fig. 90–2A). Sufficient vaginal mucosa is separated from the underlying pubocervical fascia to permit a tension-free closure of the tissues. This usually requires a fair amount of mobilization of the vagina (Figs. 90–5 and 90–6). Traction is applied to the scar tissue of the fistula, and countertraction is placed on the edges of the vaginal mucosa to facilitate accurate undermining of the vagina. The subvaginal plane is dissected in all directions. At times, entering the peritoneum facilitates mobilization of the fistulous tract (see Fig. 90–6B). If the fistulous tract is small, it can be completely excised. If large and fibrotic, the edges should be freshened (see Fig. 90–5A). Overexcision of fistulous edges may enlarge the defect and increase the risk of hemorrhage from the bladder edges postoperatively. This can cause catheter blockage, bladder distention, and failure of the repair. If mobilization proves difficult, regular circumferential vaginal incisions made at a distance from the fistula may facilitate mobilization and low-tension closure. Once hemostasis is achieved, these incisions are left open to heal. Once the tract has been excised or the edges of the fistula have been converted to a fresh injury with healthy tissue and a healthy blood supply, a layered closure is performed (see Fig. 90–2). The first layer involves interrupted 4-0 delayed absorbable sutures placed in an extramucosal fashion extending lateral to the fistulous opening. All sutures are placed and then individually tied. The initial suture line is then inverted, and a second suture line of similar sutures is placed through the muscular portion of the wall of the bladder. This row of sutures will imbricate the first layer of sutures (see Fig. 90–2). The author prefers to test the integrity of the repair at this time by instilling methylene blue or sterile milk into the bladder. Care should be taken to avoid overdistention. This ensures that the entire fistula has been identified and approximated appropriately. An attempt is then made to place a third layer of pubocervical fascia over the fistulous closure. This is placed with interrupted 3-0 delayed absorbable sutures. At times, if the peritoneum has been entered, a J-flap of omentum or a peritoneal flap can be interposed between the repaired fistula and the vagina (see Fig. 90–5C). The vaginal epithelium is closed with delayed absorbable 2-0 sutures (see Fig. 90–2). A vaginal packing is usually inserted for 24 hours postoperatively, and the bladder is drained for 1 to 2 weeks. The author considers the transurethral Foley catheter the most efficient method of drainage.

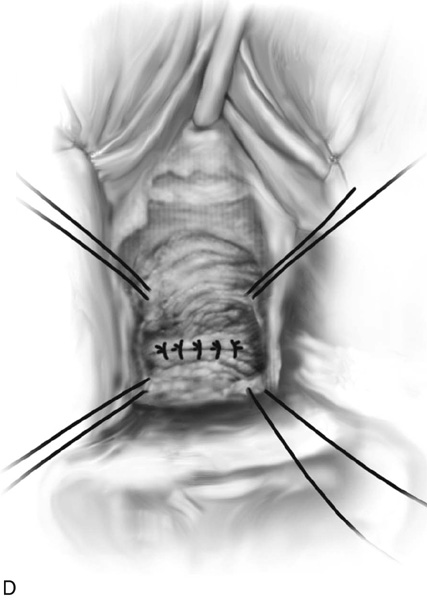

FIGURE 90–1 The Latzko technique of partial colpocleisis. A. Stay sutures are placed in the vaginal wall to assist in exposing the fistula. An initial circumferential incision is made around the fistulous tract (dashed white line). B. Sharp dissection mobilizes the vaginal mucosa for a distance of 2.5 cm in all directions. C. The vaginal edges are then approximated with delayed absorbable sutures. Note that no attempt is made to excise the fistulous tract or freshen the edges of the fistula. If possible, a second layer of pubocervical fascia is approximated over the initial layer. D. The vaginal mucosa is closed, thus completing the repair.

FIGURE 90–2 The classic method of vaginal repair of a vesicovaginal fistula. A. Stay sutures are placed to help expose the fistula. After an initial circumferential incision is made around the fistula, the fistulous tract is excised completely (smaller fistulas) or the scarred edges are cut back until fresh vascular tissue is identified (larger fistulas). B. The vaginal mucosa is widely mobilized in all directions, and the fistula is closed in layers. The initial layer involves placement of 4-0 delayed absorbable sutures in the extramucosal portion of the bladder edge. The second layer is placed through the muscular portion of the bladder wall, imbricating the first layer. C. A third layer approximates the pubocervical fascia over the bladder closure. D. The repair is completed by closure of the vaginal epithelium.

FIGURE 90–3 Intravesical view of a vesicovaginal fistula. Note that the fistula extends very close to the opening of the right ureter.

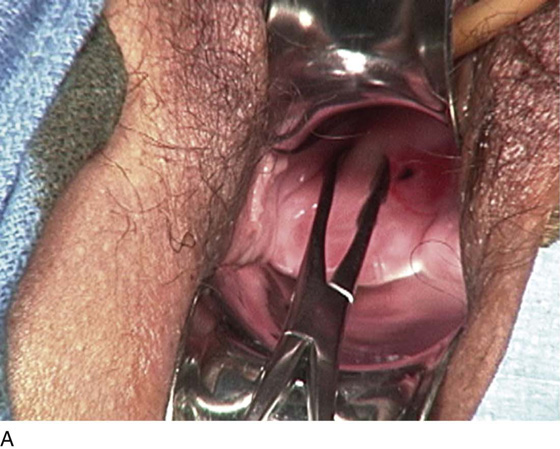

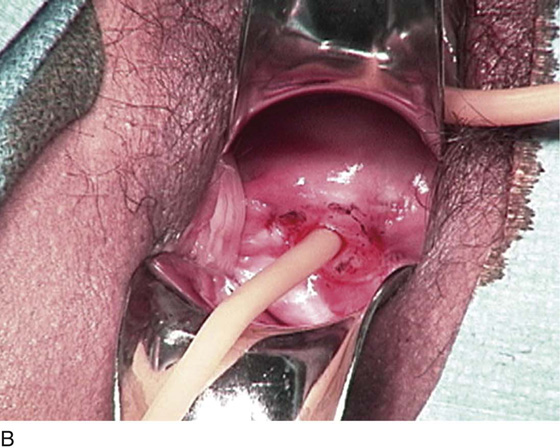

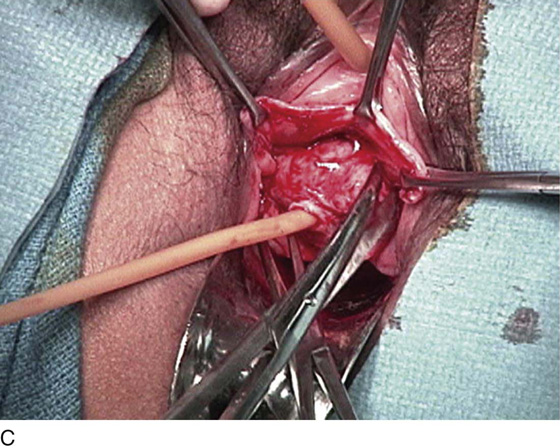

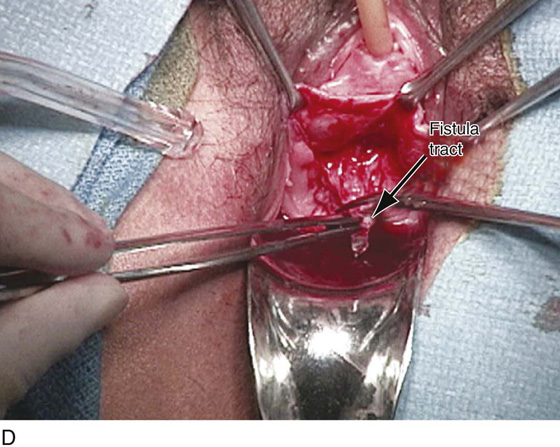

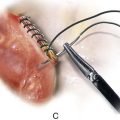

FIGURE 90–4 Vaginal repair of a vesicovaginal fistula. A. The fistula is seen at the level of the vaginal cuff. B. A pediatric Foley catheter has been placed in the fistula to facilitate the dissection of the vagina away from the underlying bladder. C. Sharp dissection is used to completely mobilize the fistulous tract from the anterior vaginal wall. D. The fistulous tract is being excised in preparation for a layered closure of the defect in the bladder.

FIGURE 90–5 Vaginal repair of a previously failed Latzko procedure. A. The scar tissue from the previous Latzko repair is grasped in preparation for excision. B. During dissection of the vagina off the anterior wall of the bladder, the peritoneum is entered, which will facilitate mobilization of the fistulous tract. C. The fistulous tract has been excised and closed in two layers. A J-flap of omentum is brought from the intraperitoneal area and interposed between the bladder and the vagina.

FIGURE 90–6 Multiple vesicovaginal fistulas. A. An intravesical view of three separate and distinct fistulous tracts. B. A Foley catheter has been placed in the largest fistulous tract. Sharp dissection is utilized to completely mobilize the fistulous tract, and the peritoneum is entered at the level of the vaginal cuff.