Vaginal Repair of Vaginal Vault Prolapse

The true incidence and prevalence of vaginal vault prolapse are unknown. Eversion of the vagina probably occurs in about 0.5% of patients who have undergone vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy. Prophylactic measures performed at the time of hysterectomy probably decrease the incidence of vaginal vault prolapse. These measures include routine reattachment of the vaginal vault to the cardinal-uterosacral ligament complex, routine use of culdoplasty sutures, and cul-de-sac obliteration or enterocele excision after removal of the uterus. When isolated uterovaginal prolapse or posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse is mild (i.e., the presenting part of the prolapse descends to the midportion of the vagina), vaginal hysterectomy with culdoplasty or a vaginal enterocele repair will usually be sufficient to relieve the patient’s symptoms and to restore normal vaginal function and vaginal length. However, when descent of the vault of the vagina or the uterus is significant, formal suspension of the apex of the vagina is necessary to preserve vaginal function. The vaginal procedures used to suspend the apex of the vagina discussed in this section include sacrospinous ligament suspension, iliococcygeus fascia suspension, and high uterosacral ligament suspension.

Sacrospinous Ligament Suspension

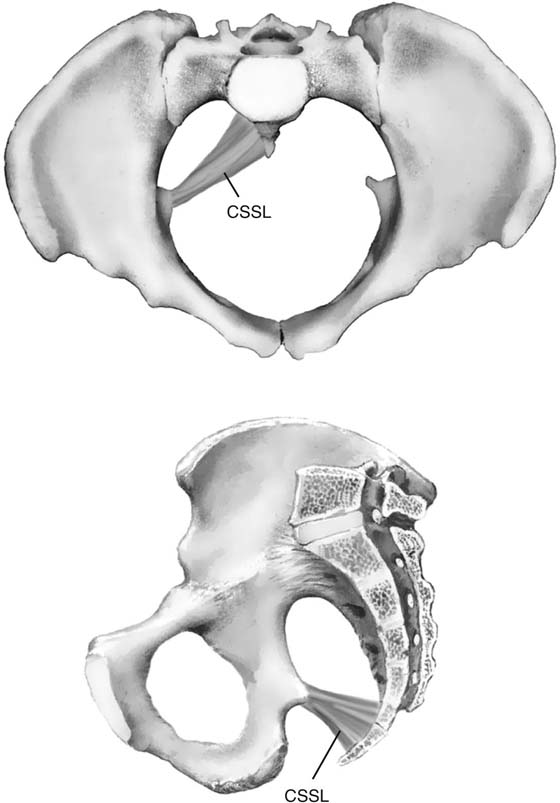

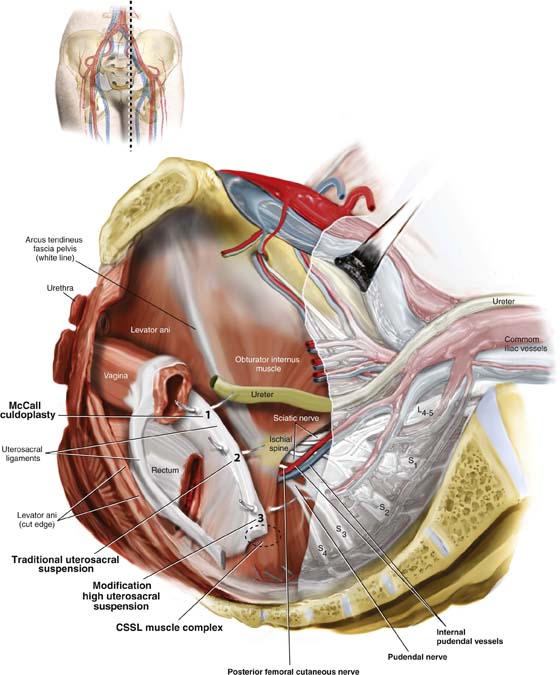

To perform this procedure correctly and safely, the surgeon must be familiar with pararectal anatomy, as well as the anatomy of the sacrospinous ligament and its surrounding structures. This area at times is difficult to expose, and when vascular complications are encountered, life-threatening hemorrhage can occur. The sacrospinous ligaments extend from the ischial spine on each side to the lower portion of the sacrum and coccyx (Fig. 55–1). The ligament itself is a cordlike structure lying within the substance of the coccygeus muscle. However, the fibromuscular coccygeus muscle and the sacrospinous ligament are basically the same structure and are best referred to as the coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex (CSSL). The coccygeus muscle has a large fibrous component that is present throughout the body of the muscle and on its anterior surface, where it appears as white ridges. The CSSL is best identified by palpating the ischial spine and tracing the flat, triangular thickening posterior to the sacrum. The coccygeus muscle and the sacrospinous ligament are directly attached to the underlying sacrotuberous ligament.

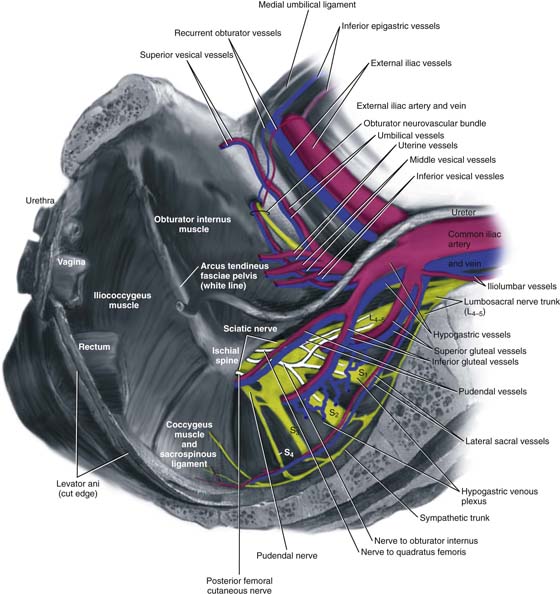

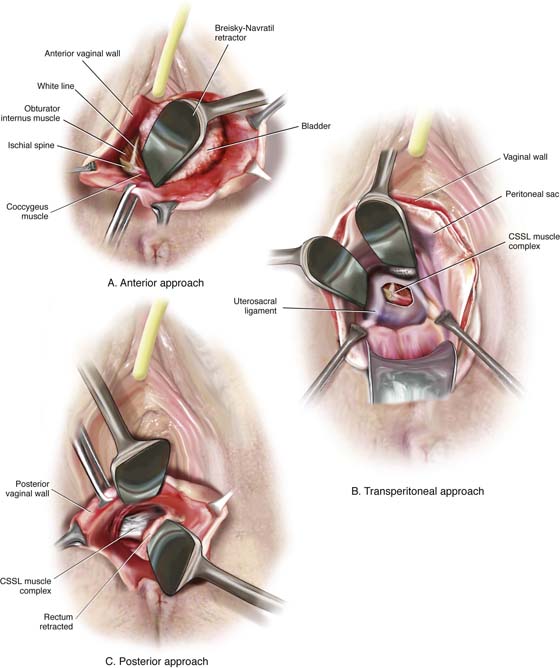

It is extremely important to appreciate the close proximity of the many vascular structures and nerves to the CSSL (Fig. 55–2). Posterior to the complex are the gluteus maximus muscle and the ischial rectal fossa. The pudendal nerves and vessels lie directly posterior to the ischial spine. The sciatic nerve lies superior and lateral. Also superiorly lies an abundant vascular supply that includes the inferior gluteal vessels and the hypogastric venous plexus (see Fig. 55–2). The CSSL complex can be exposed via posterior perirectal dissection, as well as by anterior paravaginal dissection. The ability to safely identify and palpate this structure is mandatory when a mesh prolapse kit is used (see Chapter 57). The complex also can be palpated easily transperitoneally (see Figs. 55–3 and 55–15).

FIGURE 55–1 Coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex. Note that the sacrospinous ligament lies within the coccygeus muscle.

FIGURE 55–2 Anatomy surrounding the coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex (CSSL).

FIGURE 55–3 The sacrospinous ligament can be palpated and or exposed via the (A) anterior paravaginal approach, (B) transperitoneal approach, or (C) posterior pararectal approach.

1. With the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position, the vaginal area is prepped and draped, and prophylactic perioperative antibiotics are given on call to the operating room.

2. The apex of the vagina is grasped with two Allis clamps, and downward traction is used to determine the extent of the vaginal prolapse and associated pelvic support defects. The vaginal apex is then reduced to the sacrospinous ligament intended to be used. If bilateral sacrospinous fixation is to be performed, then each side of the vaginal apex should be reduced to the respective ligament on that side. At times, the true apex of the vagina is foreshortened and will not reach the intended area of fixation. This is commonly associated with a shortened anterior vaginal wall and a very prominent enterocele. In this setting, the apex should be moved to a portion of the vaginal wall over the enterocele, thus allowing sufficient vaginal length for suspension to the sacrospinous ligament. The intended apex is tagged with sutures for later identification. If the patient has complete eversion of the vagina that requires anterior vaginal wall repair or bladder neck suspension, the author prefers to do this portion of the operation first. During this procedure, one can separate the bladder base away from the vaginal apex, thus lowering the risk of cystotomy.

3. The upper part of the posterior vaginal wall is then incised, usually at least halfway down the length of the posterior vaginal wall. The enterocele sac is mobilized off the vaginal apex and is entered and excised. If the patient has undergone a vaginal hysterectomy, the peritoneum over the posterior vaginal wall is removed to the level of the neck of the enterocele, and the enterocele is closed as previously described.

4. The next step is entering the perirectal space. The right rectal pillar separates the rectovaginal space from the right perirectal space. The rectal pillar is nothing more than areolar tissue that extends from the rectum to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis and overlies the levator muscle. It may contain a few small fibers and blood vessels. In most cases, entry into the perirectal space is best achieved by breaking through this fibroareolar tissue just lateral to the enterocele sac at the level of the ischial spine. This maneuver can usually be accomplished by gently mobilizing the rectum medially. At times, however, the use of gauze on the index finger or a tonsil clamp is necessary to break through into the space.

5. Once the perirectal space has been entered, the ischial spine is identified by palpation. With dorsal and medial movement of the fingers, the coccygeus sacrospinous ligament is palpated and its superior edge is identified.

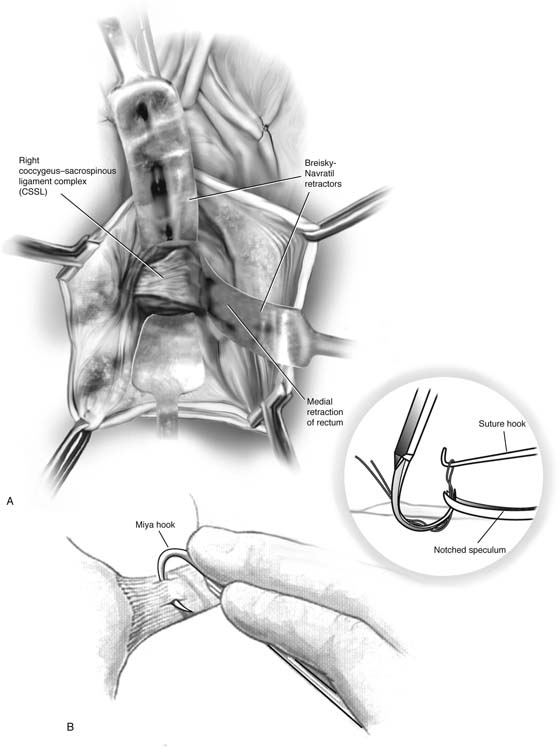

6. Blunt dissection is used to further remove tissue from this area. The surgeon should take care to ensure that the rectum is adequately retracted medially. It is recommended that a rectal examination be performed at this time to ensure that no inadvertent rectal injury has occurred. Breisky-Navratil retractors are used to expose the complex (Fig. 55–4).

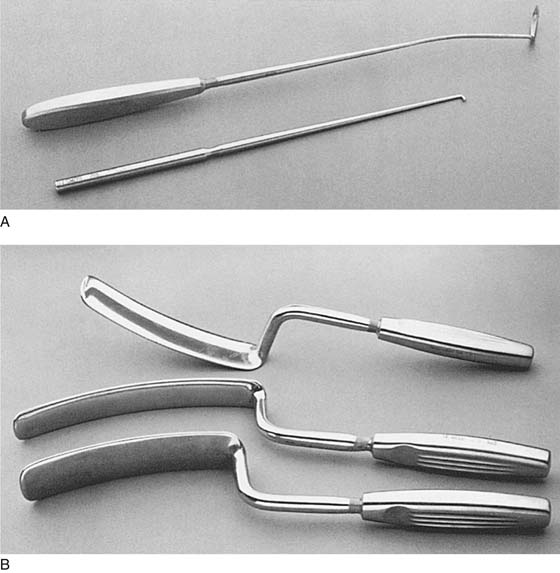

7. Two techniques have been popularized for the actual passage of sutures through the ligament. The first involves use of a long-handled Deschamps ligature carrier and nerve hook (Fig. 55–5A). Long straight retractors are used to expose the coccygeus muscle, ideally Breisky-Navratil retractors (Fig. 55–5B). One must take great care that the assistant does not let the tip of the retractor be pushed across the anterior surface of the sacrum, which would risk potential damage to the vessels and nerves. If the right sacrospinous ligament is to be used, the middle and index fingers of the left hand (in a right-handed surgeon) are placed on the medial surface of the ischial spine, and under direct vision, the CSSL is penetrated by the tip of the ligature carrier at a point two fingerbreadths medial to the ischial spine. When the ligature carrier is pushed through the body of the ligament, considerable resistance should be encountered. This must be overcome by forceful, yet controlled rotation of the handle of the ligature carrier. If visualization of the CSSL is difficult, the muscle and the ligament can be grasped in the tip of a long Babcock or Allis clamp, which helps to isolate the tissue to be sutured from underlying vessels and nerves. After the suture has been passed, the fingers of the left hand are withdrawn, the retractor is suitably repositioned, and the tip of the ligature carrier is visualized. The suture is then grabbed with a nerve hook. A second suture is placed similarly 1 cm medial to the first. To avoid a second passage of the ligature carrier, the original long suture can be cut in the center and each end of the cut loop paired with its respective free suture. This obtains two sutures through the ligament with only one penetration of the ligature carrier. To ensure that an appropriate bite of tissue has been obtained, one should be able to gently move the patient on the table with traction of the sutures.

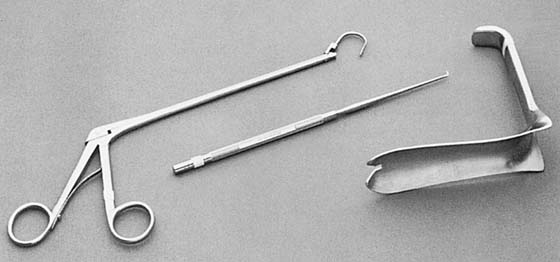

A second technique popularized for passing the sutures through the CSSL is the Miyazaki technique (Fig. 55–6). The proposed advantages of this technique are that it is safer and easier because the ligature carrier enters the CSSL under direct palpation of distinct landmarks and is then pulled down into the safe perirectal space below. To perform this modification, the tip of the right middle finger is placed on the CSSL just below its superior margin, approximately two fingerbreadths medial to the ischial spine. The Miya hook in the left hand in a closed position is slid along the palmar surface of the right hand. The hook point should come to rest just beneath the previously positioned tip of the right middle finger. The handles are then opened and lowered to a near horizontal position. This points the hook into the CSSL at about a 45° angle. If a high perineum prevents lowering of the handle, an episiotomy should be performed. With the tip of the middle finger, the hook point is placed two fingerbreadths medial to the ischial spine approximately 0.5 cm below the superior edge (see Fig. 55–4). With experience, the hook point can be passed along the superior edge. With the middle and index fingers, firm pressure is applied downward just behind the hook hump so that the hook point penetrates the CSSL. Downward pressure with two fingers on the tip plus traction with the back of the thumb on the back handle produces enough force to penetrate the ligament. The handle of the Miya hook is closed and elevated, and tissues from the hook point are pushed downward with the index and middle fingers so as to make the suture clearly visible. If too much tissue is in the hook, the hook is simply backed out a little, and a smaller bite taken. An assistant should hold the elevated handles in the closed position. A long retractor is then placed to mobilize the rectum medially, and a notched speculum is inserted by palpation under the hook point. A nerve hook is then used to retrieve the suture (see Fig. 55–4).

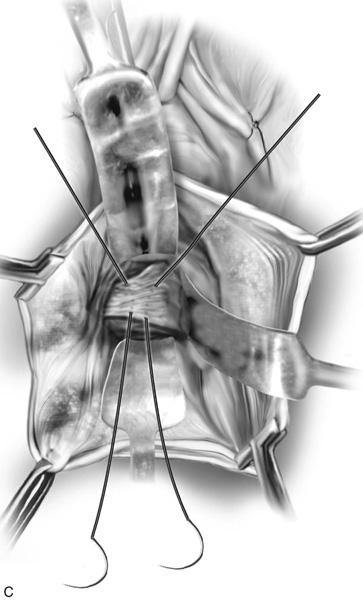

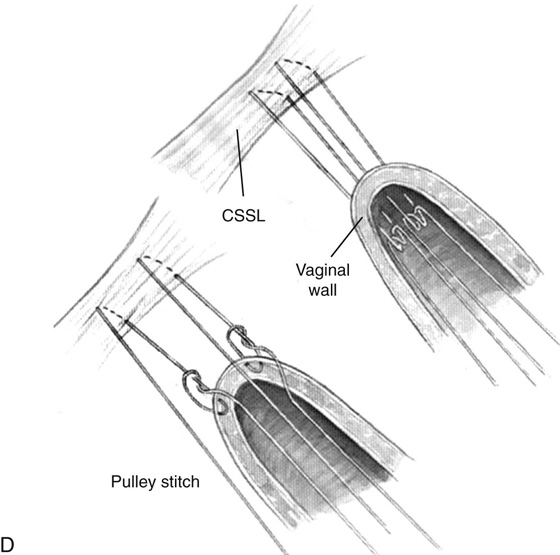

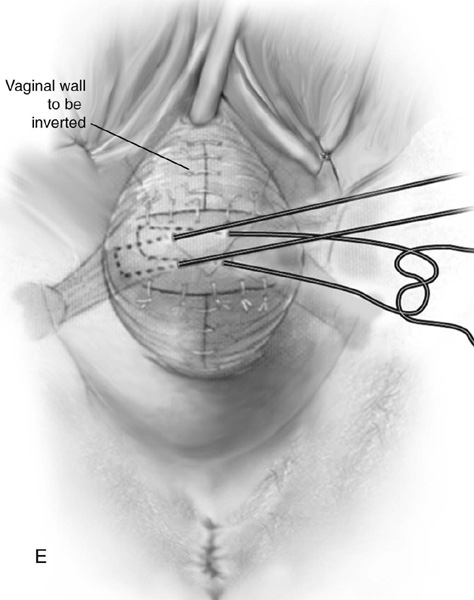

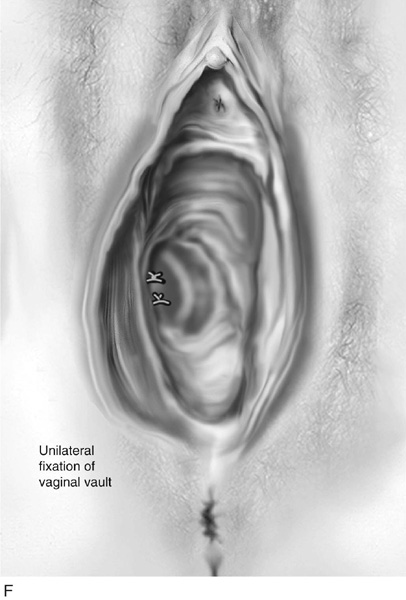

FIGURE 55–4 A. Breisky-Navratil retractors are used to retract the rectum medially and the bladder superiorly. B. Technique of passage of a Miya hook through the ligament. Inset. Technique of retrieval of the suture. C. Two sutures have been passed through the complex. D. Technique of fixing the vaginal apex to the coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex (CSSL). If a pulley stitch is performed, then permanent sutures should be used. If the sutures are passed through the vaginal epithelium and tied in the vaginal lumen, then delayed absorbable sutures should be used. E. The vagina is closed before the suspension sutures are tied. F. Tied sacrospinous sutures.

FIGURE 55–5 A. Long-handled Deschamps ligature carrier and nerve hook. Note the slight bend near the tip to facilitate suture placement into the coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex (CSSL). B. Breisky-Navratil retractors, various sizes. (From Walters MD, Karram MM: In Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 2nd ed. CV Mosby, St. Louis, 1999, with permission.)

FIGURE 55–6 Left to right: Miya hook, notched speculum, and suture hook for use during sacrospinous ligament fixation. (From Walters MD, Karram MM: In Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 2nd ed. CV Mosby, St. Louis, 1999, with permission.)

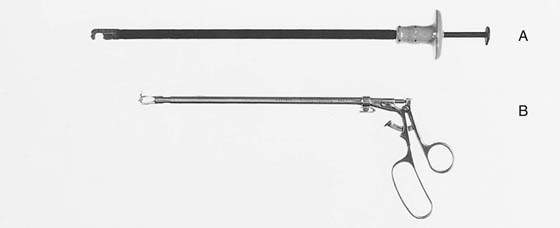

Two other instruments that are commonly utilized to facilitate passage of a suture through the ligament are the Capio needle driver (Microvasive-Boston Scientific Corp, Watertown, Mass) and the Nichols-Veronikis ligature carrier (BEI Medical Systems, Chatsworth, Calif) (Fig. 55–7).

8. Now the surgeon is ready to bring stitches out to the apex of the vagina. Two techniques are commonly performed for this maneuver. The first involves bringing the vaginal apex to the surface of the CSSL with the use of a pulley stitch (see Fig. 55–4). After the stitch has been placed in the ligament, one end of the suture is rethreaded on a free needle, sewn into the full thickness of the fibromuscular layer of the undersurface of the vaginal apex, and tied by a single half-stitch, while the free end of the suture is held long. Traction of the free end of the suture pulls the vagina directly into the muscle and ligament. A square knot then fixes it in place. With this type of fixation, a permanent suture should be used because the suture is not exposed through the epithelium of the vagina.

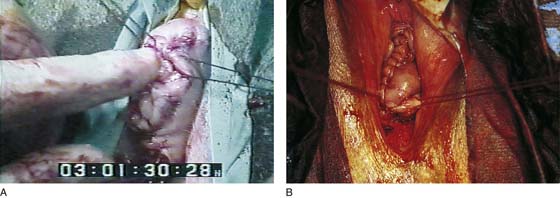

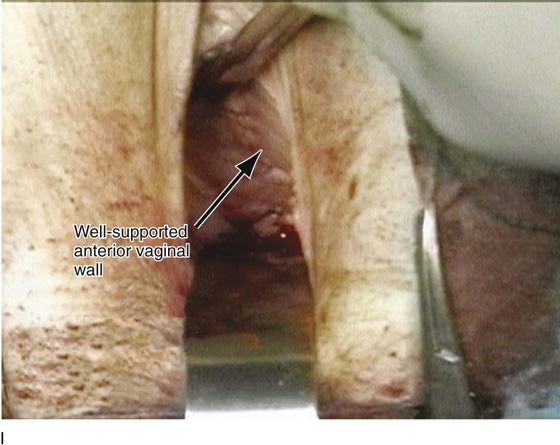

Some surgeons prefer a second technique (see Fig. 55–4), especially if the vaginal wall is thin or if greater vaginal length is desired. With this method, both ends of the sutures are passed through the vaginal epithelium. When this method is used, a delayed absorbable suture should be used because the knot remains in the vagina. We recommend a #2 delayed absorbable suture. After the sutures have been brought out through the vagina, the vagina is trimmed if necessary, and the upper portion of the vaginal wall is closed with an interrupted or continuous suture. The vaginal vault suspension sutures are then tied, thus elevating the apex of the vagina to the CSSL (Figs. 55–8 through 55–10). It is important that the vagina comes into contact with the coccygeus muscle and that no suture bridge exists, especially if delayed absorbable sutures are being used. While these sutures are being tied, it may be useful to perform a rectal examination to detect any suture bridge.

9. After these sutures are tied, the posterior colpoperineorrhaphy is completed as needed, and the vagina is packed with moist gauze for 24 hours.

FIGURE 55–7 Two specially designed instruments to facilitate passage of sutures through the sacrospinous ligament. A. Capio needle driver (Microvasive-Boston Scientific Corp, Watertown, Mass). B. Nichols-Veronikis ligature carrier (BEI Medical Systems, Chatsworth, Calif). (From Walters MD, Karram MM: In Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery, 2nd ed. CV Mosby, St. Louis, 1999, with permission.)

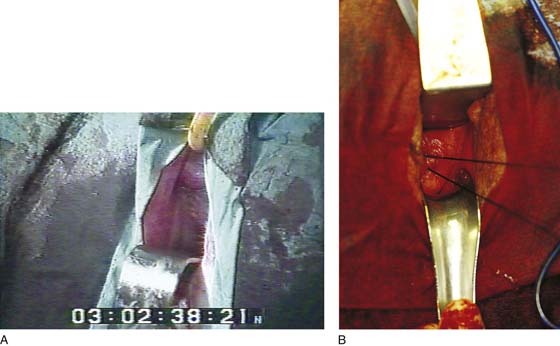

FIGURE 55–8 A and B. Two examples of cases in which sacrospinous ligament fixation has been performed. The anterior vaginal wall and the vaginal cuff have been closed. Sacrospinous suspension sutures have been brought out through the vaginal apex.

FIGURE 55–9 A and B. Two examples of cases in which sacrospinous ligament fixation has been performed. Sutures are being tied, approximating the apex of the vagina to the coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex (CSSL). Note that the vagina is distorted posteriorly and to the right.

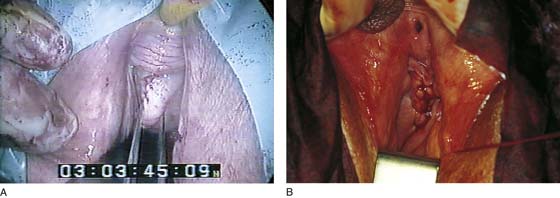

FIGURE 55–10 The anterior vaginal wall after tying of the sacrospinous sutures. A. An Allis clamp has been placed on the anterior vaginal wall, which is the segment of the prolapse most likely to recur. B. Note the posterior distortion of the anterior segment after tying of the sacrospinous sutures.

Iliococcygeus Fascia Suspension

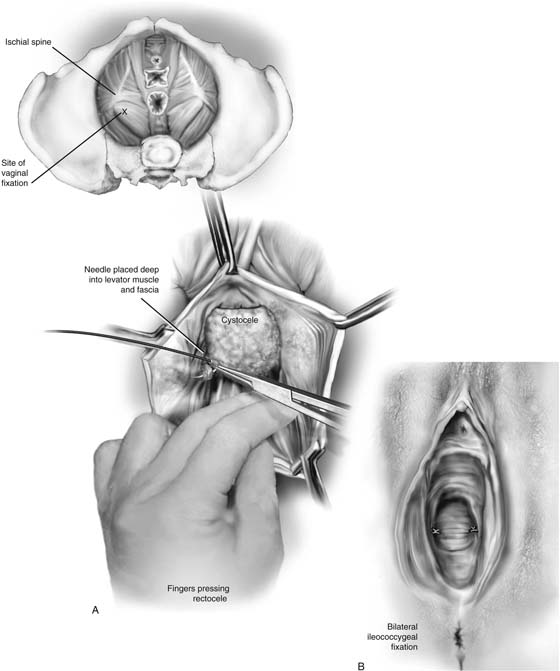

In 1963, Inmon described bilateral fixation of the everted vaginal apex to the iliococcygeal fascia just below the ischial spine. The technique for this repair is as follows:

1. The posterior vaginal wall is opened in the midline as for posterior colporrhaphy, and the rectovaginal spaces are dissected widely to the levator muscles bilaterally.

2. The dissection is extended bluntly toward the ischial spine.

3. With the surgeon’s nondominant hand pressing the rectum downward and medially, an area 1 to 2 cm caudad and posterior to the ischial spine in the iliococcygeus muscle and fascia is exposed (Fig. 55–11). A single, 0 delayed absorbable suture is placed deeply into the levator muscle and fascia. Both ends of the suture are then passed through the ipsilateral posterior vaginal apex and are held with a hemostat. This is repeated on the opposite side.

4. The posterior colporrhaphy is completed, and the vagina is closed. Both sutures are tied, while the posterior vaginal apices are elevated (see Fig. 55–11). This repair is often done in conjunction with a culdoplasty or uterosacral suspension.

High Uterosacral Ligament Suspension

Another popular approach to the management of enterocele and vault prolapse is based on the anatomic observation that connective tissue of the vaginal tube does not stretch or attenuate but rather breaks at specific definable points. This concept has been discussed briefly in the section on posterior vaginal wall defects (see Chapter 54).

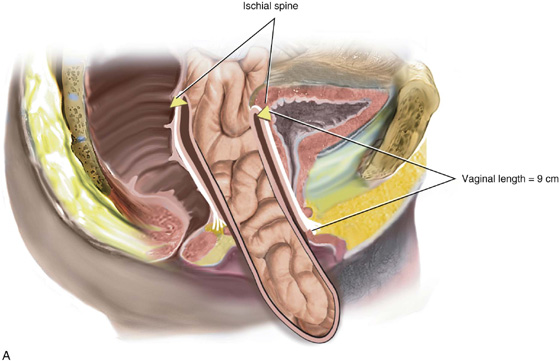

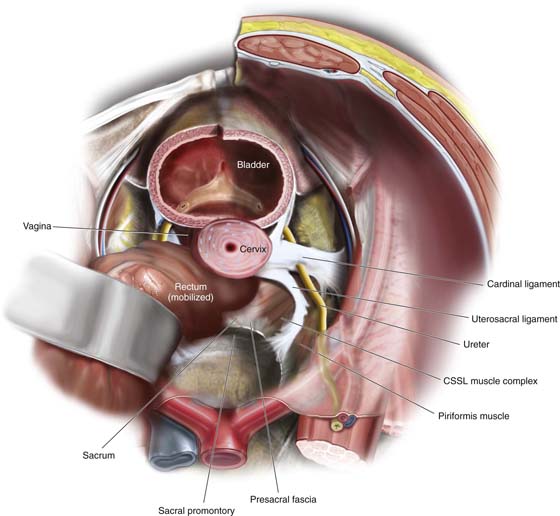

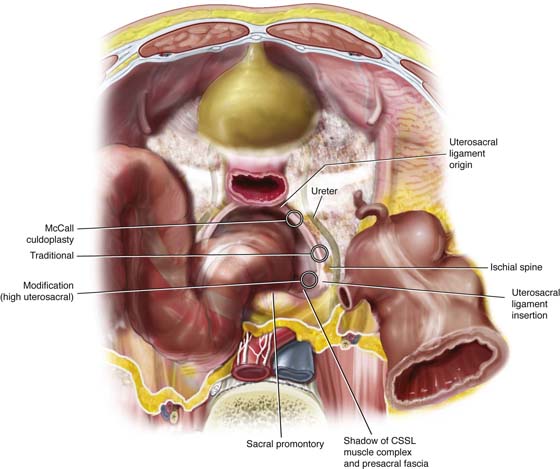

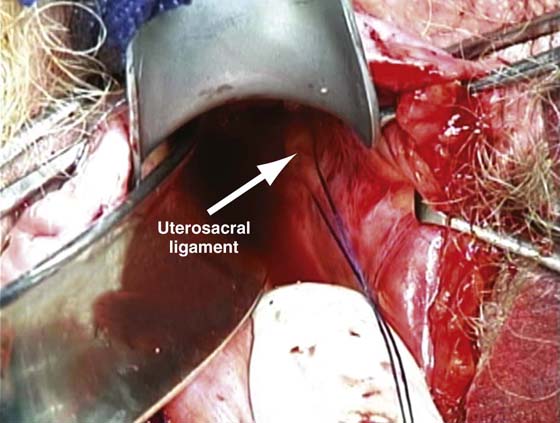

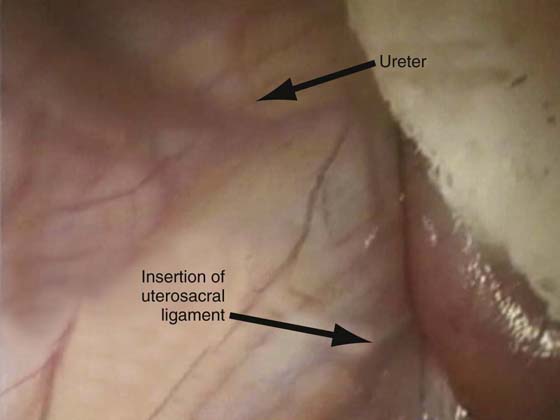

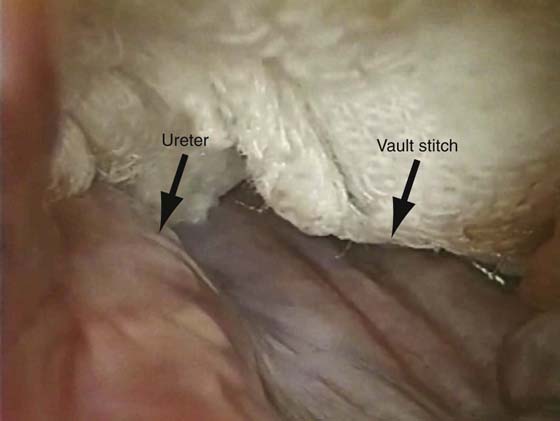

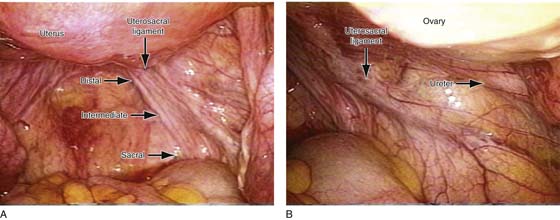

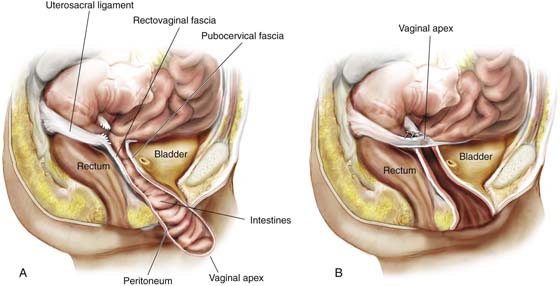

A uterosacral ligament suspension requires entrance into the peritoneum as it is an intraperitoneal suspension. This is currently the author’s preferred procedure for vaginal vault prolapse because it can be utilized for all degrees of prolapse. Since it does not significantly distort the vaginal axis, it does not predispose the patient to recurrent anterior or posterior vaginal wall prolapse. The procedure can be easily tailored for a particular prolapse, depending on the extent of the vault prolapse and whether coexistent anterior and posterior vaginal wall defects are present. Figure 55–12 demonstrates three degrees of vaginal vault prolapse. The goal of any vault suspension should be to re-create a well-supported, functional vagina of appropriate length. A suspension to the level of the ischial spines usually results in a vagina that is at least 9 cm in length. The complexity of such a repair is based on how much coexistent anterior and posterior vaginal wall eversion is present. Figure 55–12A illustrates an isolated vaginal vault prolapse secondary to an apical enterocele with well-supported anterior and posterior vaginal walls. In such a situation, all that is required is excision of the enterocele sac and closure of the defect at the level of the neck of the enterocele. In contrast, Figure 55–12C demonstrates complete vault prolapse in conjunction with complete eversion of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Such a situation requires a much more complex repair to reconstruct a functional, well-supported vagina of appropriate length. Over the years, intraperitoneal procedures utilized to support or suspend the vaginal apex as well as address apical or posterior enteroceles have evolved. A McCall culdoplasty (see Chapter 53), originally described in 1957, remains a very good procedure that can be utilized at the time of a vaginal hysterectomy because it suspends the vagina to the plicated distal portions of the uterosacral ligaments. A traditional high uterosacral suspension attempts to pass sutures bilaterally through the uterosacral ligament at the level of the ischial spine. More recently, we have modified our technique to pass the sutures higher and more medially. Figure 55–13 illustrates the anatomy of the uterosacral ligament and surrounding structures. Figures 55–14 through 55–17 illustrate placement of sutures for McCall culdoplasty, traditional uterosacral suspension, and a modified high uterosacral suspension. Note the modified technique attempts to pass sutures that incorporate a portion of the CSSL muscle complex or the presacral fascia (see Figs. 55–14 and 55–15). Figure 55–18 is an intraperitoneal photograph of the uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligament as it inserts into the CSSL complex. This modified high uterosacral suspension has led to the creation of a deeper vagina and has significantly reduced the rate of ureteral compromise (Figs. 55–19 and 55–20). The technique of high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension (Fig. 55–21) is as follows:

1. The vaginal apex is grasped with two Allis clamps and incised with a scalpel. The vaginal epithelium is dissected off the enterocele sac up to the neck of the hernia. The enterocele is opened, exposing intraperitoneal structures.

2. Numerous moist tail sponges are placed in the posterior cul-de-sac. A wide retractor is used to elevate the sponges and the intestines out of the pelvis, thus exposing the uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligament on each side (see Fig. 55–18).

3. Allis clamps are placed at approximately 5 o’clock and 7 o’clock, incorporating the peritoneum and the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall. Downward traction on the Allis clamp allows palpation of the uterosacral ligament on each side. The ischial spines are palpated transperitoneally, and the ureter can usually be palpated along the pelvic sidewall anywhere from 1 to 5 cm ventral and lateral to the ischial spine.

4. Two to three delayed absorbable sutures are passed through the uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligament on each side. Each of these sutures is individually tagged.

5. The delayed absorbable sutures that previously had been passed through the uterosacral ligament are individually brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall.

6. If indicated, an anterior colporrhaphy is performed at this time.

7. After appropriate trimming, the vagina is closed and the vault sutures are tied, elevating the vaginal apex high up to the uterosacral ligaments on each side.

FIGURE 55–11 Ileococcygeus fascia suspension. A. With the surgeon’s finger pressing the rectum downward, the right ileococcygeus fascia suture is placed. Inset. Approximate location of the ileococcygeus fascia sutures. B. Bilateral ileococcygeus fascia suspension.

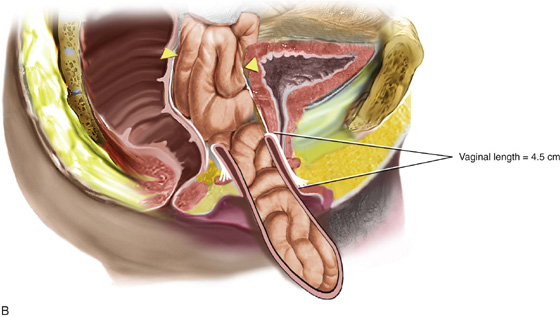

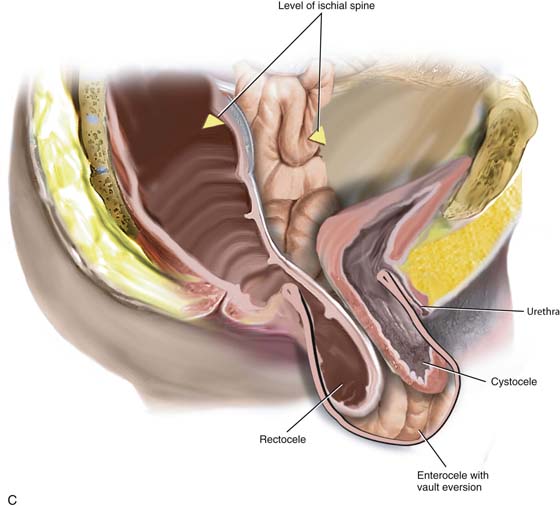

FIGURE 55–12 A. Vaginal vault prolapse in isolation. Note the good support of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Such a situation simply requires excision of the enterocele sac and closure of the defect at the level of the neck. This will support the apex of the vagina, maintaining adequate vaginal length. B. Fifty percent of the length of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls is everted. Such a situation would require suspension of the apex to the level of the ischial spine, in conjunction with restoration of support of the upper portion of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. C. Complete vaginal vault prolapse with complete eversion of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. Such a situation requires a much more complex repair, in that the prolapsed vaginal vault now needs to be suspended high up into the pelvic cavity to the level of the ischial spines. This must be done in conjunction with other procedures that would need to be performed to provide durable support to the anterior and posterior vaginal walls.

FIGURE 55–13 Demonstrates the anatomy of the support of the uterus and upper vagina. Note the relationship between the uterosacral ligament, the ureter, the CSSL muscle complex, and the presacral fascia.

FIGURE 55–14 Intraperitoneal view of the uterosacral ligament with circles demonstrating suture placement for McCall culdoplasty, traditional uterosacral suspension, and modified high uterosacral suspension. Note the close proximity of the ureter to the uterosacral ligament.

FIGURE 55–15 Cross-section of the pelvic floor demonstrating intraperitoneal placement of sutures for (1) McCall culdoplasty, (2) traditional uterosacral suspension, and (3) modified high uterosacral suspension. Note that high uterosacral suspension may involve passage of the suture through the CSSL muscle complex, as a portion of the uterosacral ligament inserts into this structure.

FIGURE 55–16 Suture placement for traditional uterosacral suspension. Note that the suture is passed through the upper portion of the uterosacral ligament just below the level of the ischial spine.

FIGURE 55–17 Suture placement for modified high uterosacral suspension. Note that the suture is passed above and medial to the ischial spine, incorporating the coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex (CSSL) or the presacral fascia.

FIGURE 55–18 An intraperitoneal photograph of the uppermost portion of the right uterosacral ligament. Note that a portion of this structure inserts directly into the coccygeus–sacrospinous ligament complex (CSSL).

FIGURE 55–19 An intraperitoneal photograph shows the relationship between the right ureter and the uppermost portion of the right uterosacral ligament.

FIGURE 55–20 Intraperitoneal photograph illustrating the location of the suture for modified high uterosacral suspension. Note that the suture is placed at least 2 cm medial to the ureter.

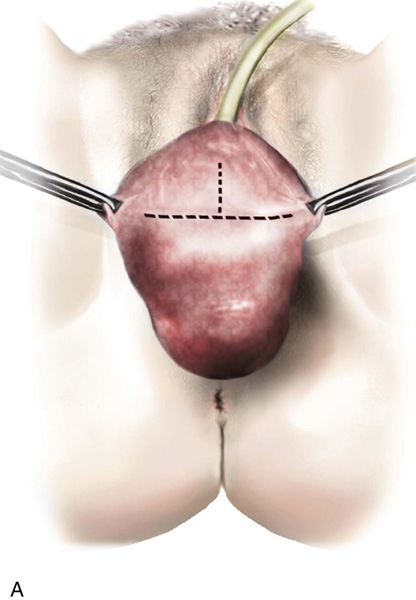

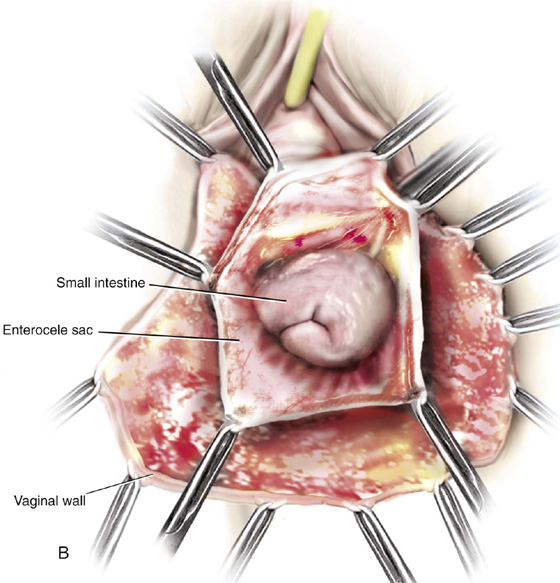

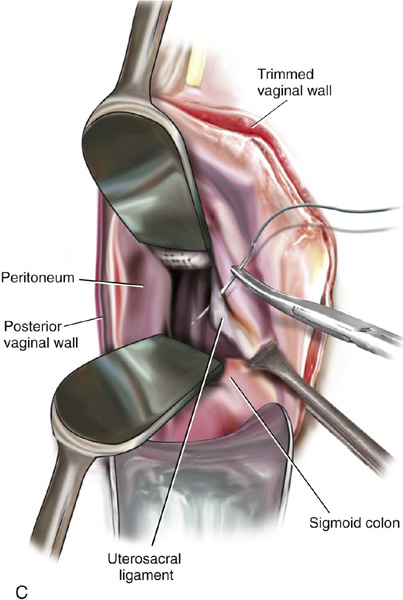

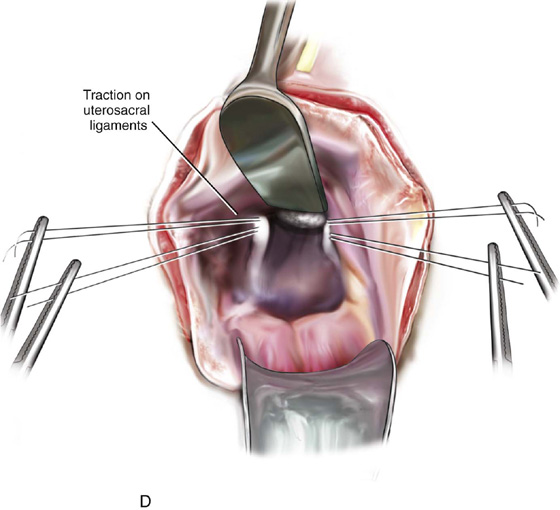

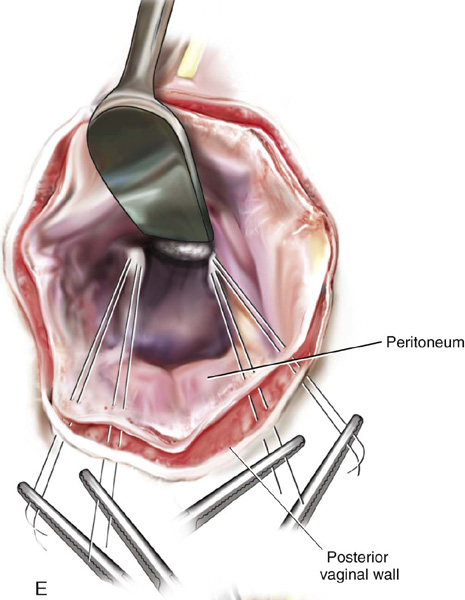

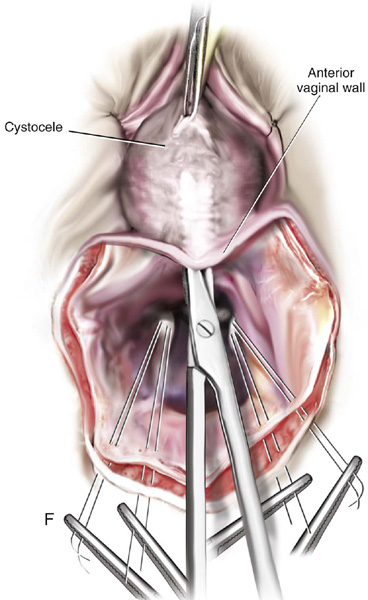

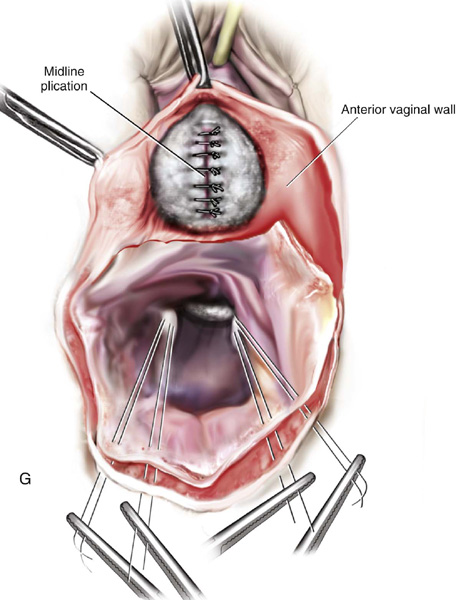

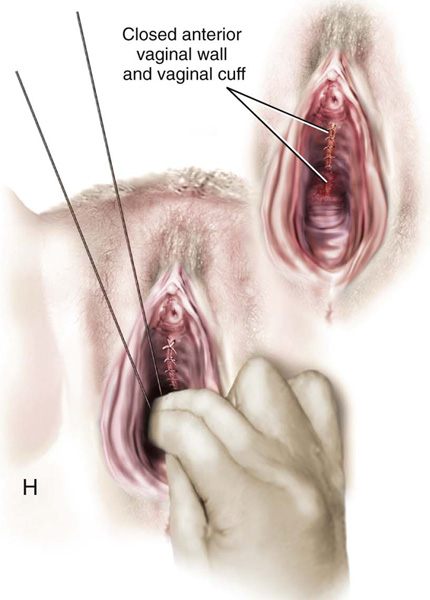

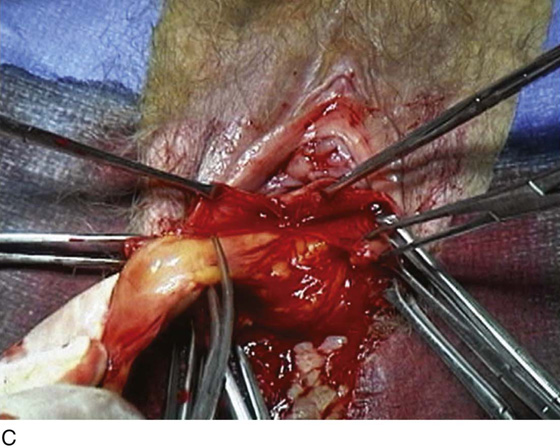

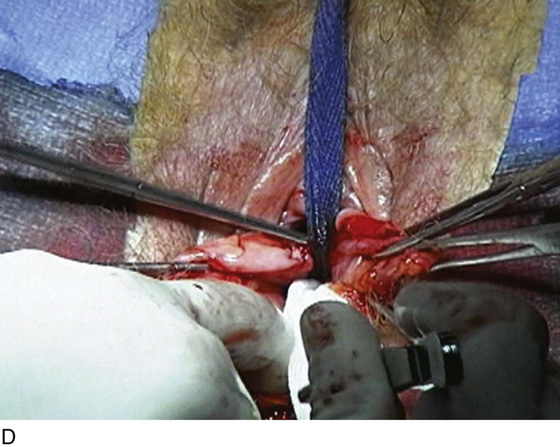

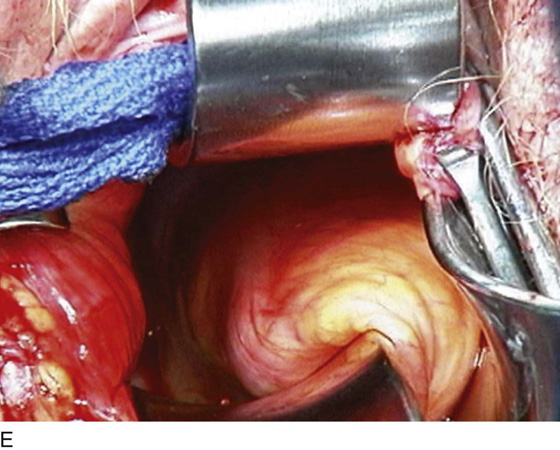

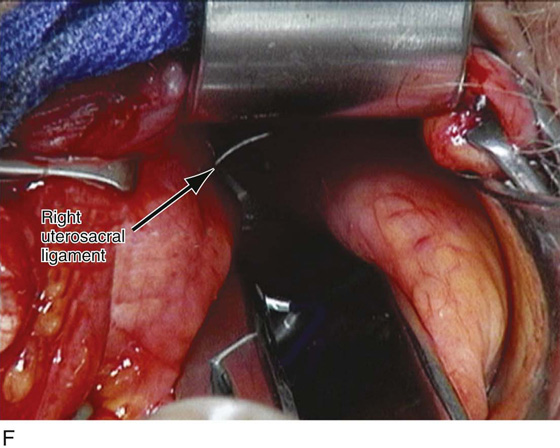

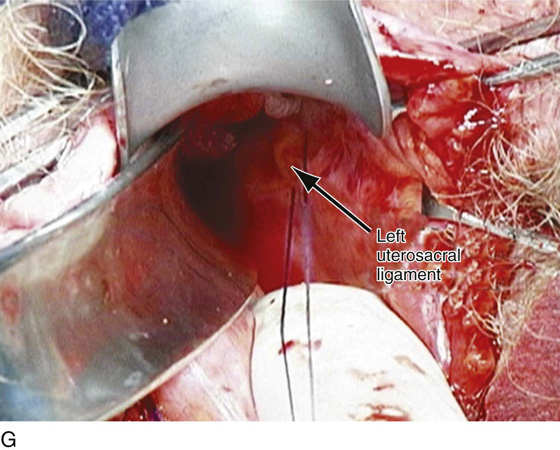

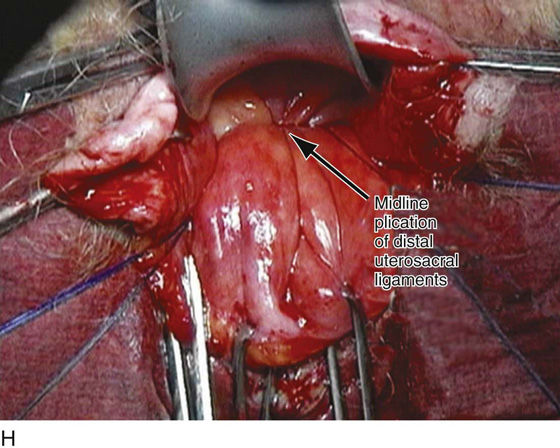

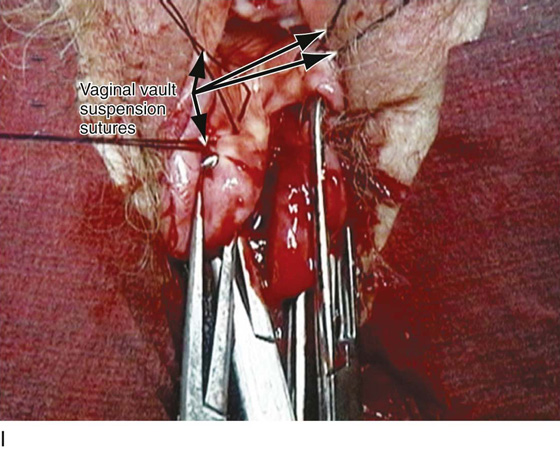

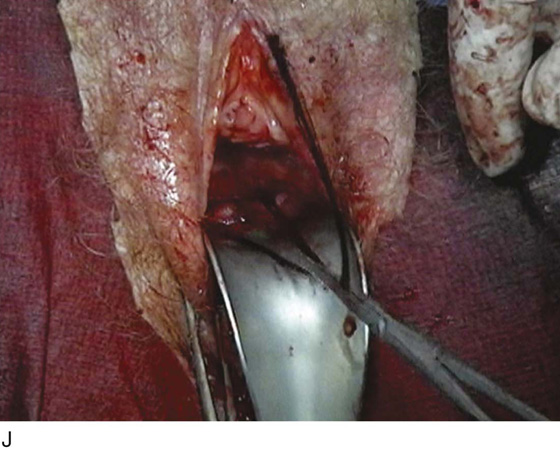

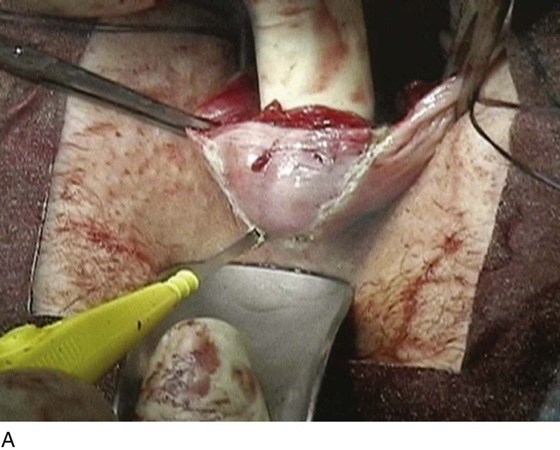

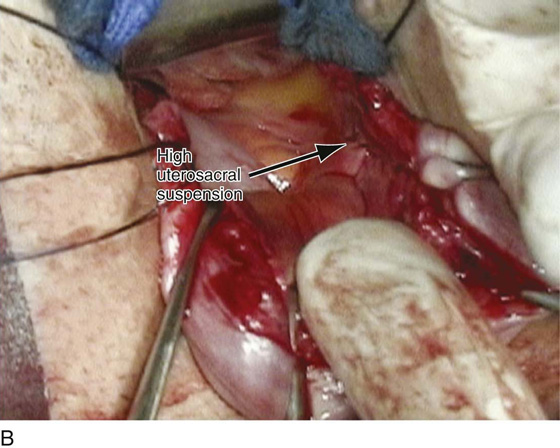

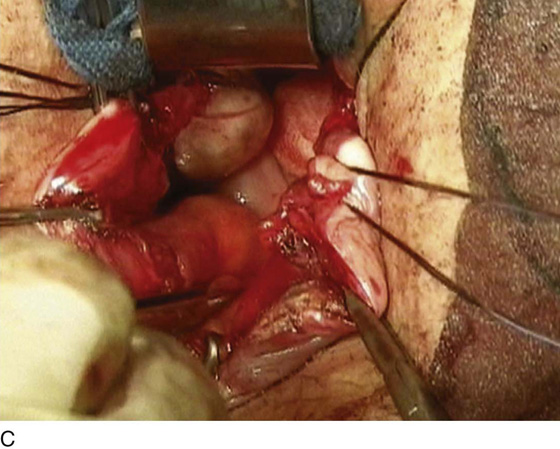

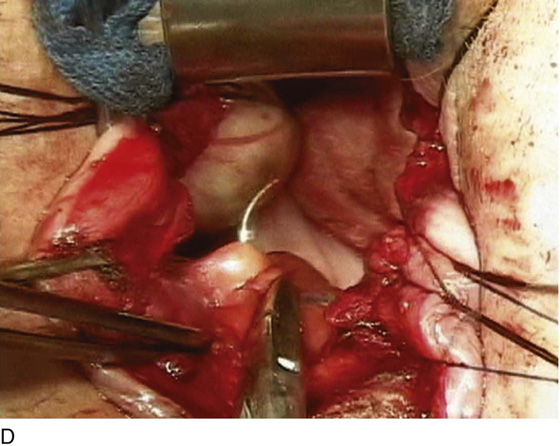

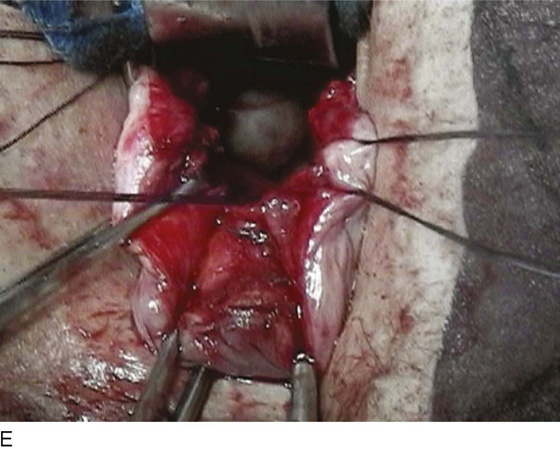

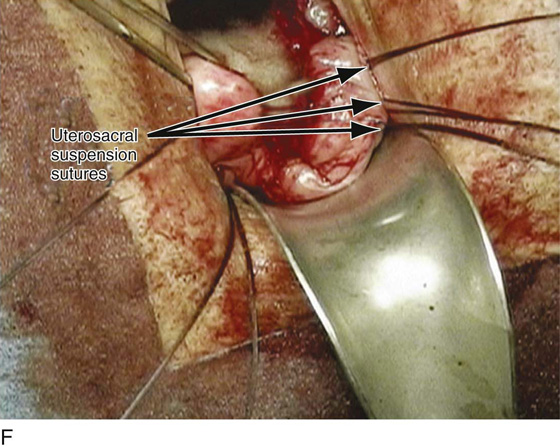

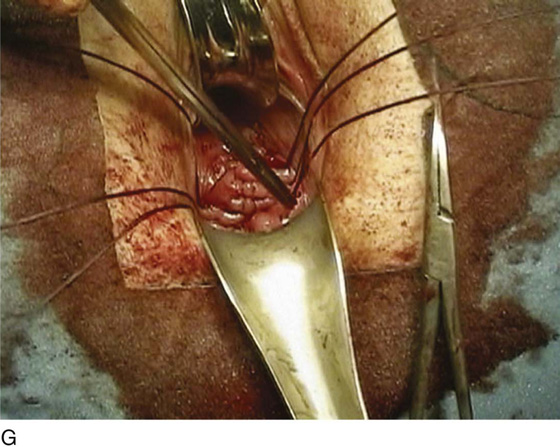

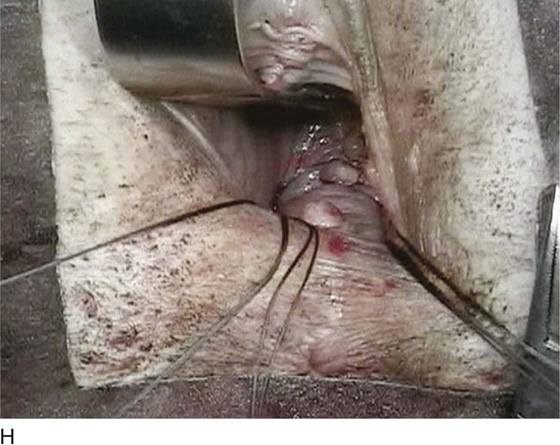

FIGURE 55–21 Technique for high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension. A. The most prominent portion of the prolapsed vaginal vault is grasped with two Allis clamps. B. The vaginal wall is opened up, and the enterocele sac is identified and entered. C. The bowel is packed high up into the pelvis using large laparotomy sponges. The retractor lifts the sponges up out of the lower pelvis, thus completely exposing the cul-de-sac. When appropriate traction is placed downward on the uterosacral ligaments with an Allis clamp, the uterosacral ligaments are easily palpated bilaterally. D. Delayed absorbable sutures have been passed through the uppermost portion of the uterosacral ligaments on each side and have been individually tagged. E. Each end of the previously passed sutures is brought out through the posterior peritoneum and the posterior vaginal wall. (A free needle is used to pass both ends of these delayed absorbable sutures through the full thickness of the vaginal wall.) F. The anterior colporrhaphy is begun by initiating a dissection between the prolapsed bladder and the anterior vaginal wall. G. The anterior colporrhaphy has been completed. H. The vagina has been appropriately trimmed and closed with interrupted or continuous delayed absorbable sutures. After closure of the vagina, the delayed absorbable sutures that were previously brought out through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall are tied, thereby elevating the prolapsed vaginal vault high up into the hollow of the sacrum.

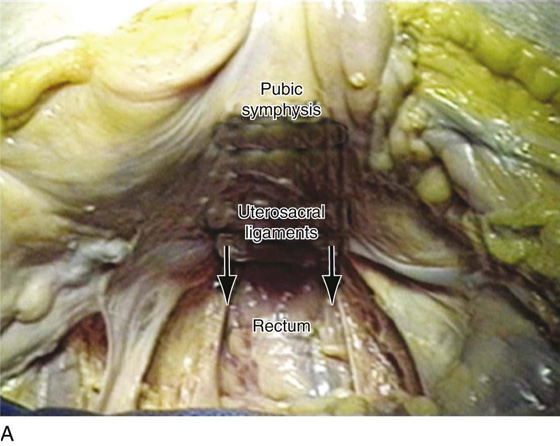

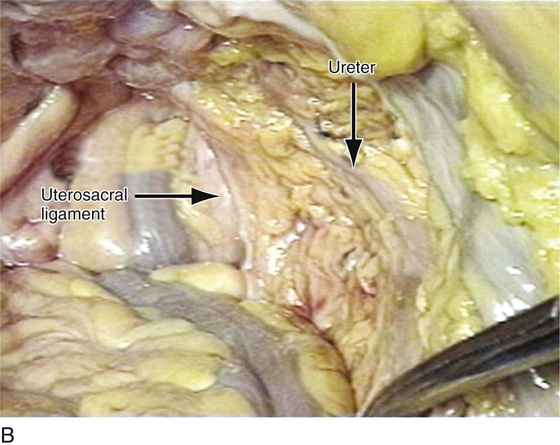

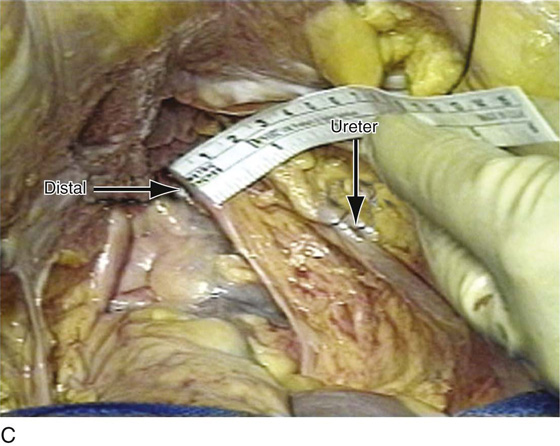

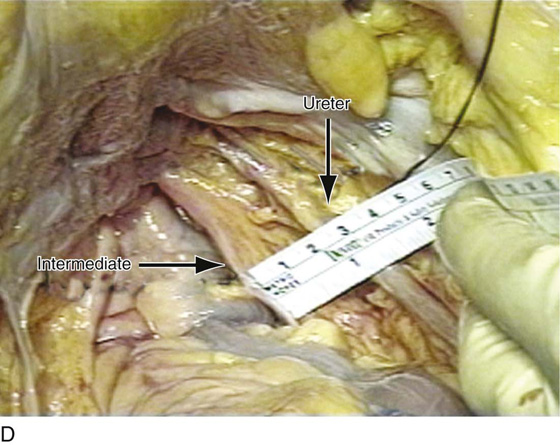

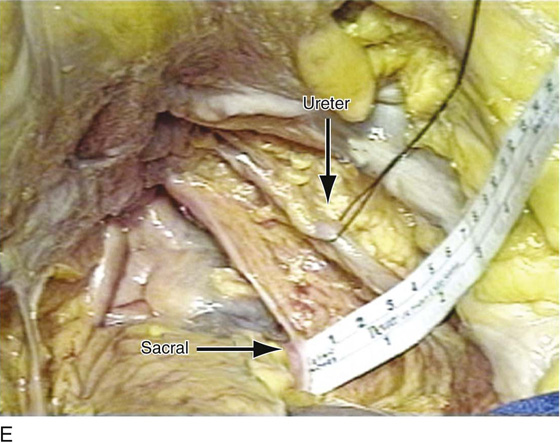

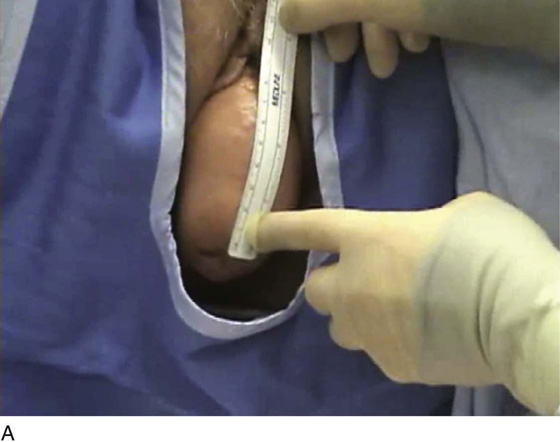

Figures 55–22 and 55–23 illustrate important anatomic relationships between the uterosacral ligaments and surrounding structures. Figures 55–24 and 55–25 show two examples of cases in which a traditional uterosacral suspension is performed. Figure 55–26 demonstrates the increased vaginal length that can be obtained when a modified high uterosacral suspension is performed. Figure 55–27 illustrates the high suspension of the vaginal apex with the creation of a normal vaginal axis. Figure 55–28 compares vaginal shape and configuration after traditional uterosacral suspension and modified high uterosacral suspension.

FIGURE 55–22 Important anatomic relationships between the uterosacral ligament and surrounding structures with cadaveric dissection. A. An abdominal view of the uterosacral ligaments as they relate to the rectum. B. Abdominal view of the uterosacral ligaments and their relationship to the ureter. C. The distal uterosacral ligament is noted to be 2.5 cm medial to the ureter in this specific cadaveric dissection. D. The relationship between the intermediate portion of the uterosacral ligament and the ureter. Again, the ureter is 2.5 to 3 cm lateral to this portion of the uterosacral ligament. E. The relationship between the ureter and the uppermost portion or the most proximal portion of the uterosacral ligament. The ureter is approximately 3.5 cm lateral to this portion of the uterosacral ligament. (Compliments of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

FIGURE 55–23 Laparoscopic view of the relationship between the uterosacral ligament and the other pelvic organs. A. Note that the distal, intermediate, and sacral portions of the uterosacral ligament are demonstrated on the patient’s right side. B. Note the relationship of the uterosacral ligament to the right ureter viewed laparoscopically. (Compliments of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.)

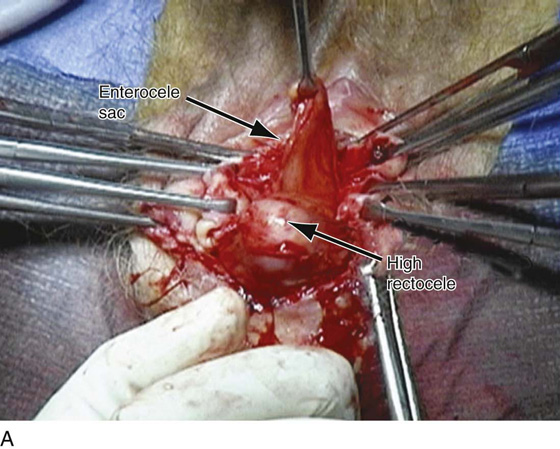

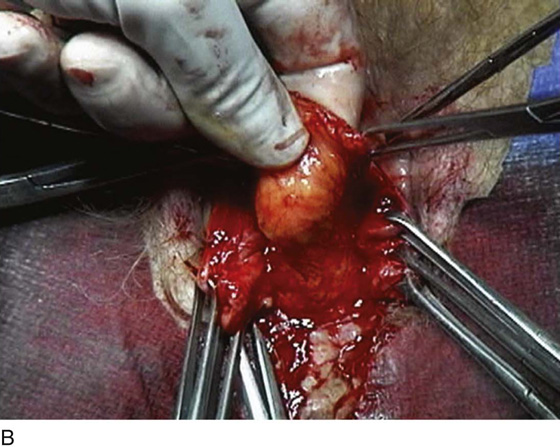

FIGURE 55–24 Technique for traditional uterosacral suspension. A. The patient has a large posterior vaginal wall defect. A high rectocele and the enterocele sac have been identified. B. The enterocele sac has been entered, and the cul-de-sac is being palpated in preparation for excising the peritoneal sac. C. The peritoneal sac is being excised. D. The intraperitoneal contents have been packed with large laparotomy tail sponges to facilitate exposure of the posterior cul-de-sac. E. A large retractor has been placed intraperitoneally, and the lap sponges have been elevated high up into the abdomen, thus nicely exposing the entire cul-de-sac. F. The right uterosacral ligament has been identified, and a delayed absorbable suture has been passed through the right uterosacral ligament at the level of the ischial spine. G. The left uterosacral ligament has been identified, and a delayed absorbable suture has been passed through the ligament at the level of the ischial spine. H. The distal portion of the cul-de-sac has been plicated across the midline with permanent sutures. I. The sutures previously passed through the uterosacral ligament on each side have now been passed through the full thickness of the vaginal wall at the level of the apex of the vagina. The vagina has been closed, and the vaginal vault stitches have been tied. J. Note the excellent elevation of the apex of the vagina high up into the hollow of the sacrum, without any significant distortion of the vaginal axis.

FIGURE 55–25 Technique of a high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension in a patient who has undergone a vaginal hysterectomy. A. Note that the cul-de-sac is being palpated and excess posterior vaginal skin and peritoneum are being excised. B. Uterosacral suspension sutures have been passed on the patient’s left side. These again are delayed absorbable sutures that are individually tagged. C. The distal portion of the cul-de-sac is visualized in preparation for midline plication. D. A permanent suture is being passed across the cul-de-sac to plicate the distal portions of the uterosacral ligaments. E. The permanent sutures that were previously passed to plicate the distal portions of the uterosacral ligaments are now tied in the midline, creating midline support of the cul-de-sac. F. The sutures that were previously passed through the upper portion of the uterosacral ligament are now individually taken out through the posterolateral aspects of the vaginal vault. G. The vagina has been closed. H. The vaginal vault sutures have been tied. Note the excellent elevation of the apex of the vagina into the hollow of the sacrum without any significant distortion of the vaginal apex. I. Note the normal support of the anterior vaginal wall after the apical sutures have been tied.

FIGURE 55–26 A. Patient with complete uterine procidentia and vaginal eversion extending 11 cm beyond the introitus. B. View of the suspended vaginal vault after vaginal hysterectomy with repairs and modified high uterosacral vaginal vault suspension. C. Note that the vagina is 11 cm in length after completion of the repair.

FIGURE 55–27 A. Cross-section of pelvis demonstrating enterocele and vaginal vault prolapse. B. Cross-section of the pelvis after excision of the enterocele sac and suspension of the vaginal apex to the uppermost portions of the uterosacral ligaments.

FIGURE 55–28 Vaginal shape and configuration after bilateral traditional uterosacral suspension (white trapezoid) versus high modified uterosacral suspension (black trapezoid).

Christine Vaccaro

Christine Vaccaro