Vaginal Repair of Cystocele, Rectocele, and Enterocele

Anterior Vaginal Wall Prolapse

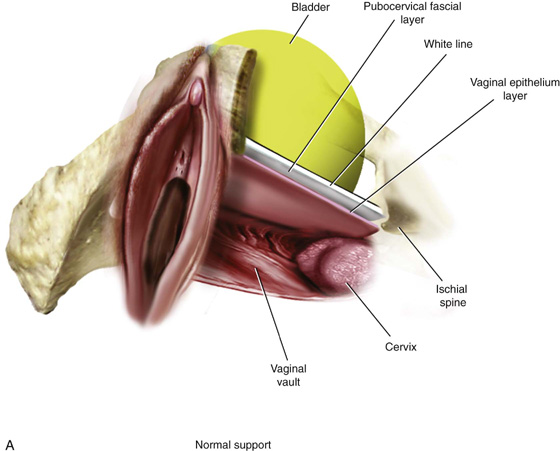

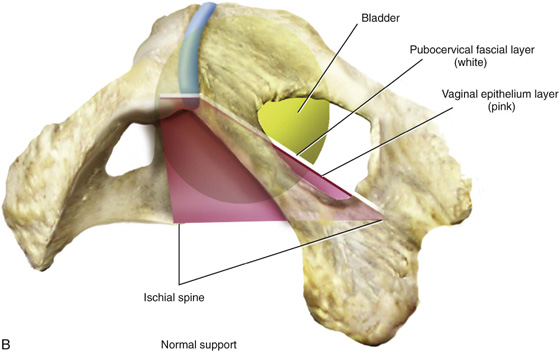

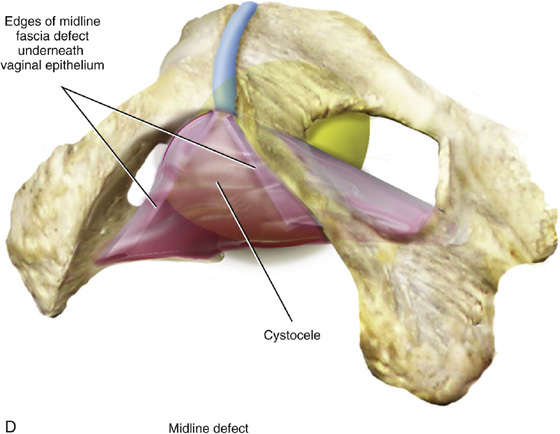

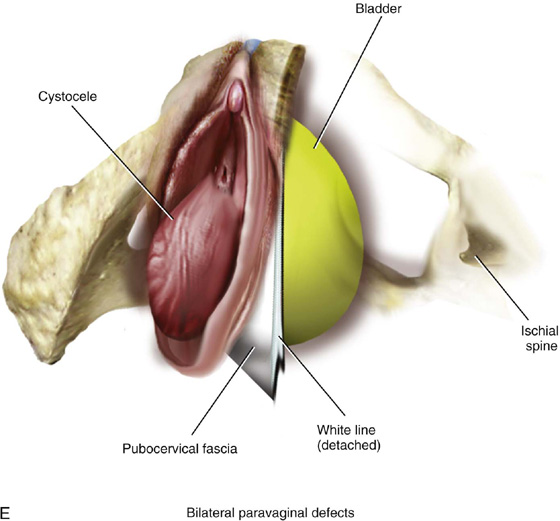

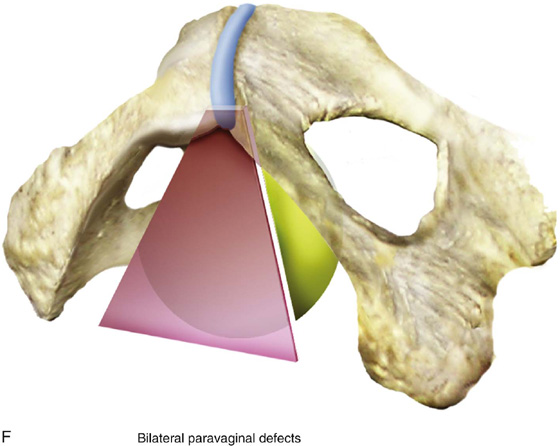

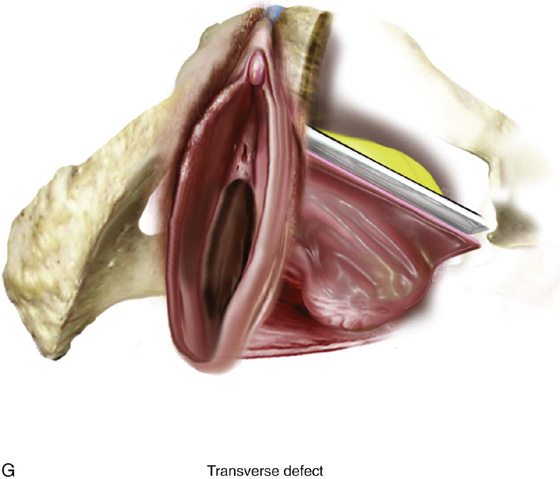

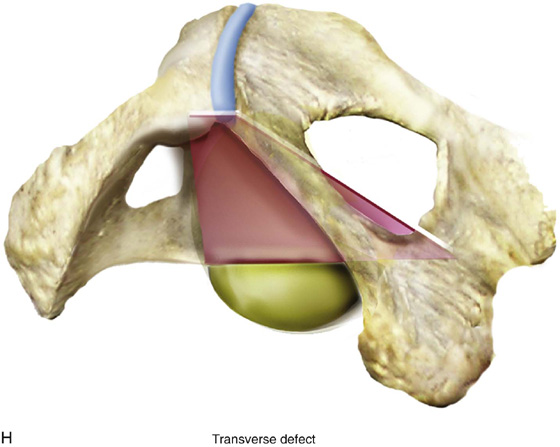

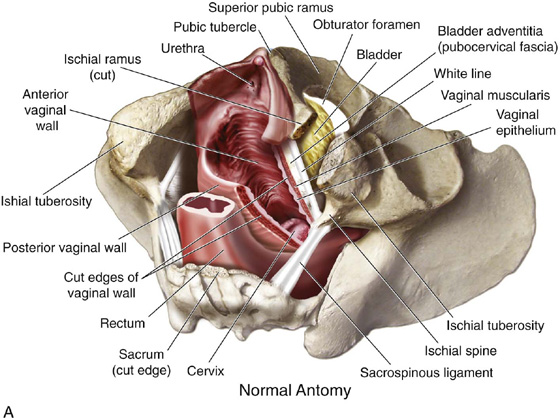

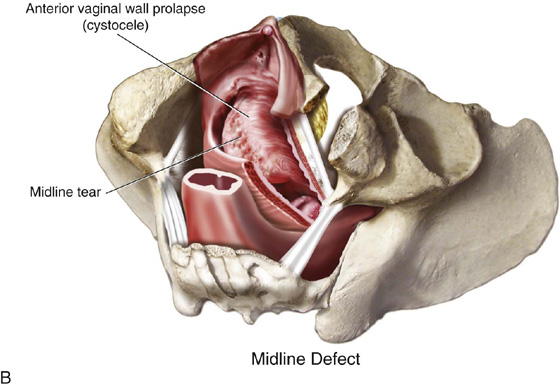

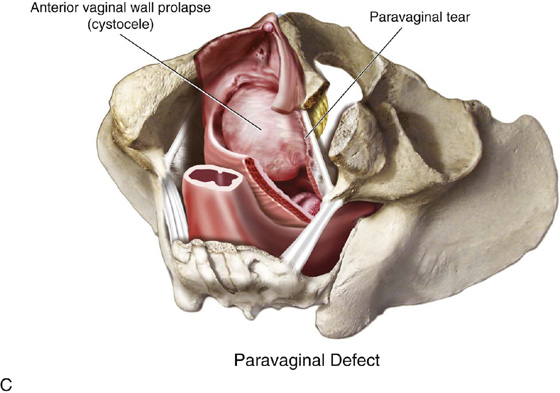

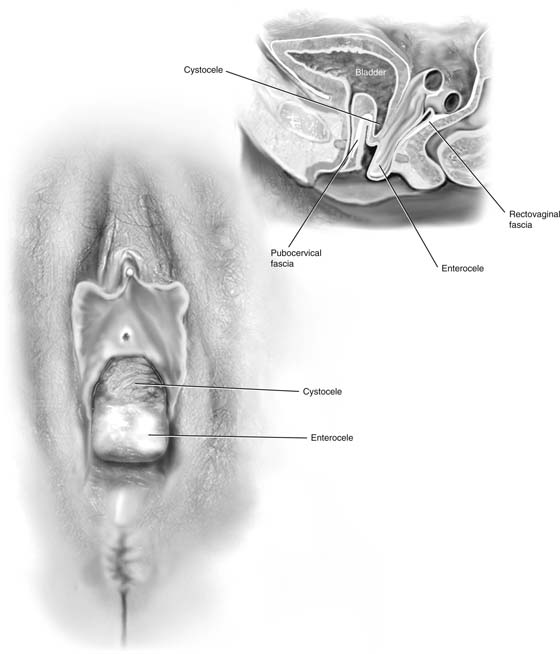

Anterior vaginal wall prolapse, or cystocele, is defined as pathologic descent of the anterior vaginal wall and overlying bladder base. The cause of anterior vaginal wall prolapse is not completely understood but is probably multifactorial, with different factors implicated in individual patients. Until recently, two types of anterior vaginal wall prolapse were described: distention and displacement cystocele. Distention cystocele was thought to result from overstretching and attenuation of the anterior vaginal wall, and displacement cystocele was attributed to pathologic detachment or elongation of the anterior lateral vaginal supports to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. More recently, three distinct defects have been described that can result in anterior vaginal wall prolapse. The midline defect is what has been previously described as a distention-type cystocele; the paravaginal defect, which is a separation of the normal attachment of the connective tissue of the vagina at the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (white line); and the transverse defect, which occurs when the pubocervical fascia separates from its insertion around the cervix or at the apex (Figs. 54–1 through 54–5). Anterior vaginal wall prolapse, especially in the posthysterectomy patient, may be commonly associated with an apical enterocele, or more rarely a true anterior enterocele (Fig. 54–6).

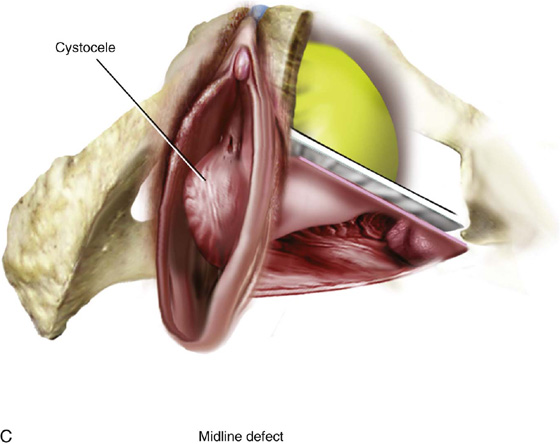

FIGURE 54–1 Two views of normal and abnormal support of the anterior vaginal wall. A. Lateral view of normal anterior vaginal wall support with bladder support extending back to the level of the ischial spines. Note normal midline and lateral support. B. Trapezoid concept of the support of the anterior vaginal wall. Note that the trapezoid extends back to the ischial spine on each side, and the fascia or the muscular lining of the vagina extends from one side of the pelvic sidewall to the opposite side with good midline support and lateral and transverse attachments. C. Lateral view of a midline defect. Note the bulging of the bladder into the midportion of the vagina with maintenance of lateral support. Thus, the anterior vaginal fornix is maintained on each side. D. Midline defect demonstrates weakening in the midportion of the trapezoidal support of the anterior segment. E. Lateral view of bilateral paravaginal defects. Note the complete detachment of the white line from its normal attachment, resulting in complete loss of the anterolateral supports of the anterior segment. F. Bilateral paravaginal defects. Complete lateral detachment of the normal support is noted as the trapezoid rotates outwardly. G. Lateral view of a transverse defect. Note that the bladder prolapse is between the normal upward attachment and the cervix or vaginal apex, usually resulting in what is termed a high cystocele. H. Note that the bladder descends around the normal upper attachment of the fascia or the muscular lining of the vagina.

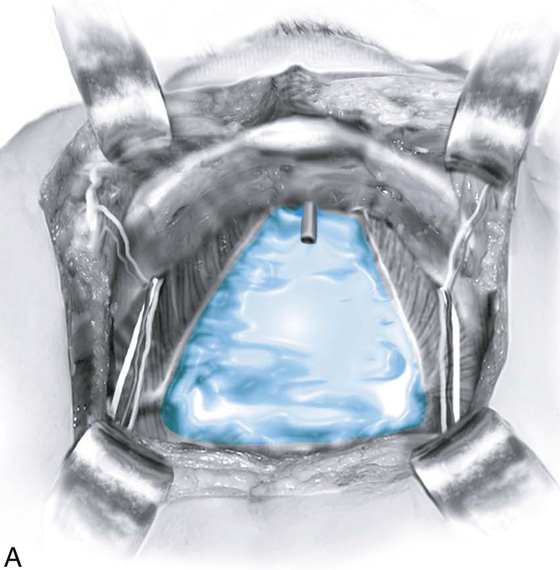

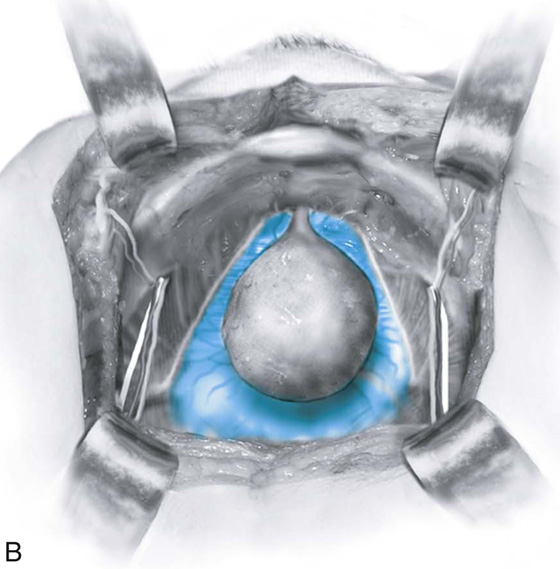

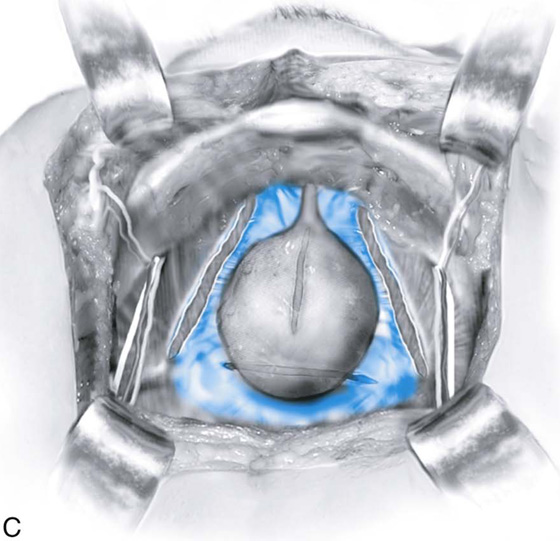

FIGURE 54–2 Normal support of the anterior vaginal wall when viewed retropubically. A.Note: The bladder has been removed. The bluish area depicts the inside lining of the fascia or the muscular lining of the vagina. In a normally supported anterior segment, this is a trapezoid-shaped support that extends from the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis on one side all the way to the opposite side, with the support extending all the way back to the level of the ischial spine laterally and to the apex or the cervix transversely. B. The bladder has been placed back into the illustration to show its normal anatomic position. C. Different possible types of defects, noting paravaginal, midline, and transverse defects.

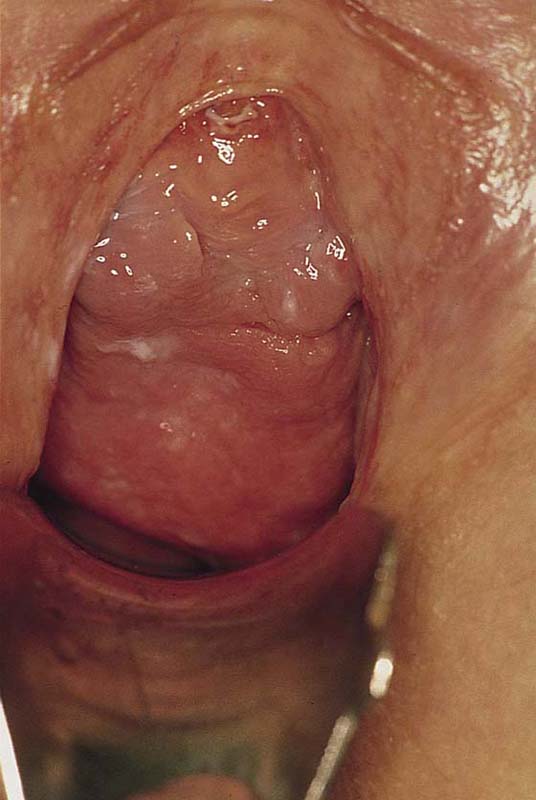

FIGURE 54–3 The anterior vaginal wall showing the urethrovaginal crease. Note that the vagina over the bladder base shows minimal rugae, a situation that is more consistent with a midline defect.

FIGURE 54–4 The anterior vaginal wall with rugae, a situation that is more consistent with a paravaginal defect.

FIGURE 54–5 Cross-sectional drawing of the pelvic floor to demonstrate (A) normal anatomy, (B) a midline defect of the anterior vaginal wall, and (C) a lateral or paravaginal defect of the anterior vaginal wall.

FIGURE 54–6 Loss of anterior vaginal wall support. A cystocele that is coexistent with an apical or possibly an anterior enterocele in the posthysterectomy patient. Note that grossly the vaginal epithelium over an enterocele will appear to be much thinner than the vaginal epithelium over the prolapsed bladder.

Midline Cystocele Repair

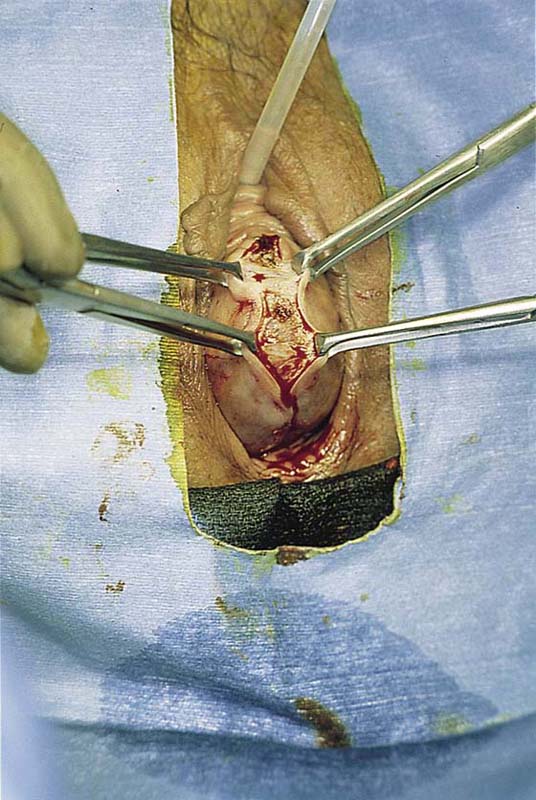

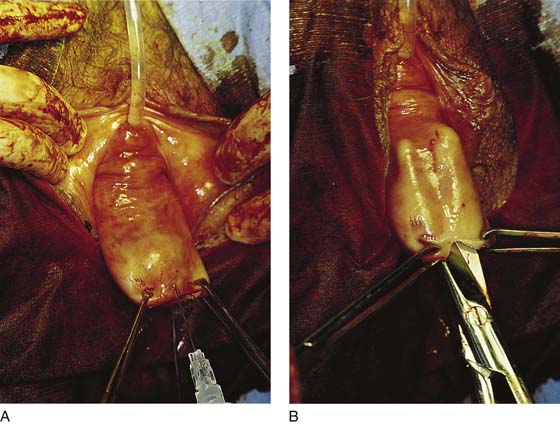

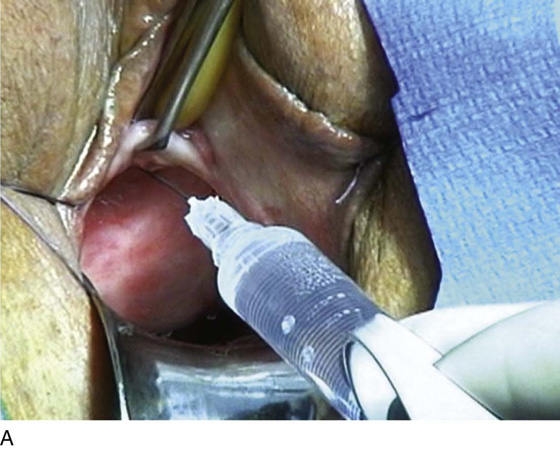

The objective of a midline anterior repair is to plicate the layers of the vaginal muscularis and adventitia overlying the bladder (pubocervical fascia). The operative procedure begins with the patient in the supine position and situated and prepped as for vaginal hysterectomy. A urethral Foley catheter is inserted for easy identification of the bladder neck. The anterior vaginal wall is then opened up via a midline incision (Fig. 54–7). If a vaginal hysterectomy has been performed, the incision is begun at the apex of the vagina by grasping this area with two Allis clamps (Fig. 54–8). Some prefer to inject a hemostatic solution before making any incisions. These various agents have been described in the chapter on vaginal hysterectomy. If there is only bladder base descensus and the bladder neck is well supported or has been previously supported via a retropubic suspension or sling procedure, then the incision need only extend to the level of the bladder neck. However, in most circumstances urethral hypermobility is present, and thus the anterior vaginal wall incision should extend to the level of the proximal urethra to allow for suburethral plication.

FIGURE 54–7 Posthysterectomy cystocele showing the initial midline anterior vaginal wall incision.

FIGURE 54–8 A. Injection (hydrodistention) of the anterior vaginal wall. Note that Allis clamps grasp the anterior vaginal wall at the vaginal apex after completion of vaginal hysterectomy. B. The scissors are separated, creating an appropriate plane for midline anterior vaginal wall dissection.

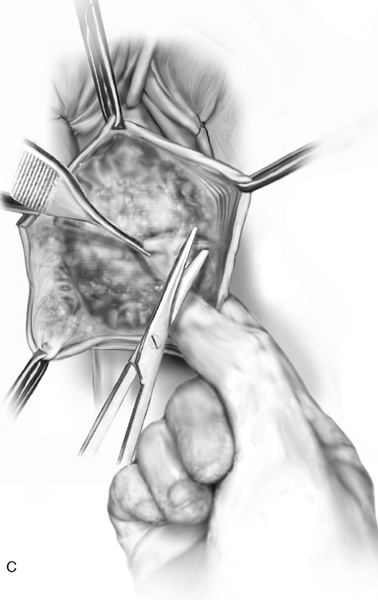

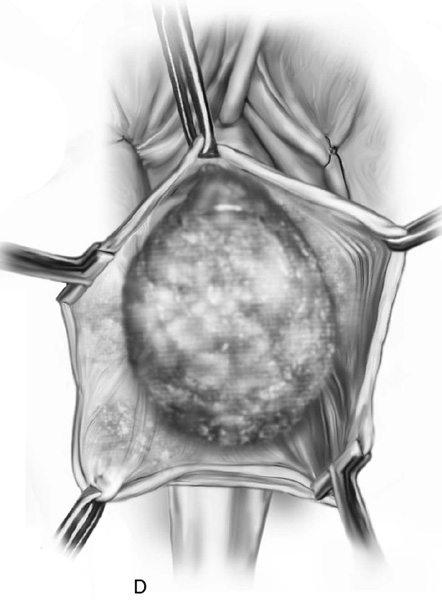

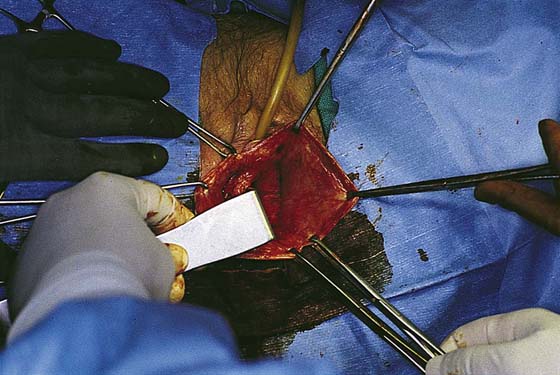

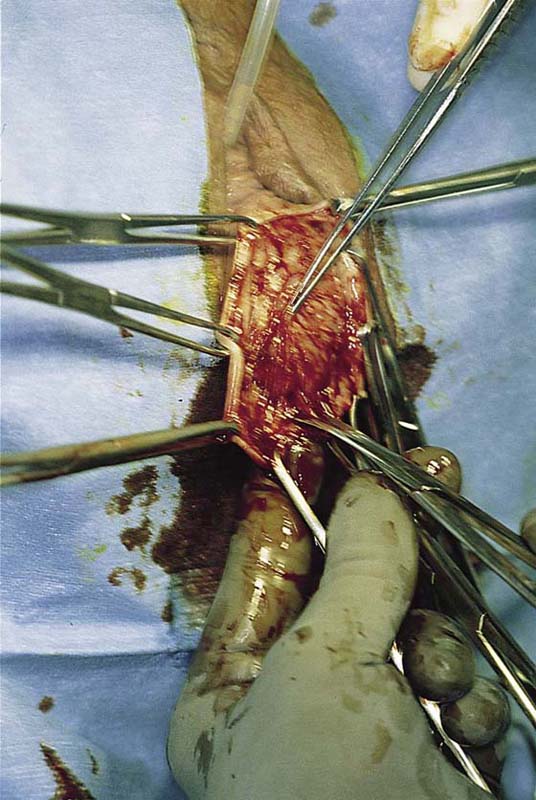

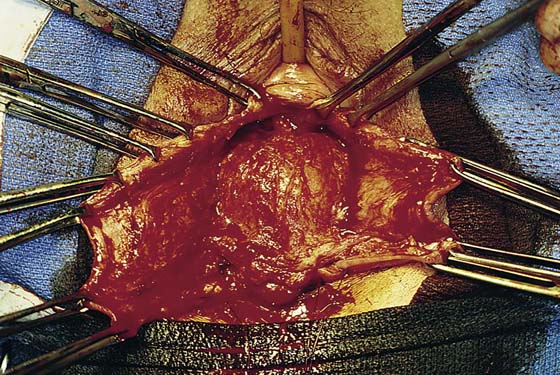

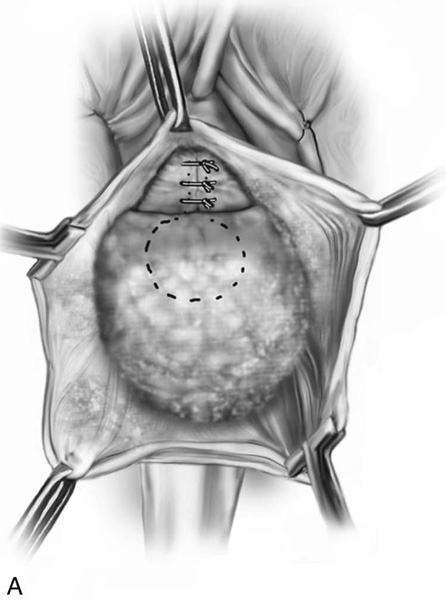

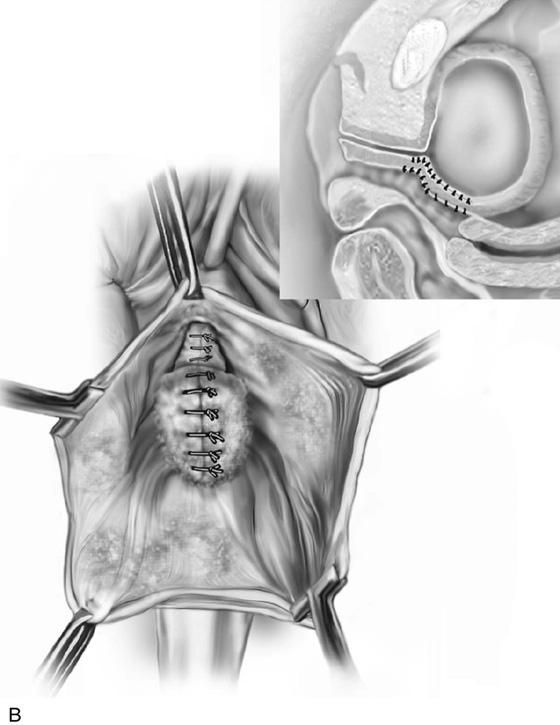

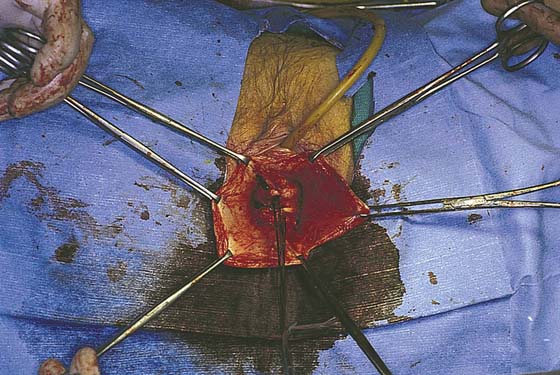

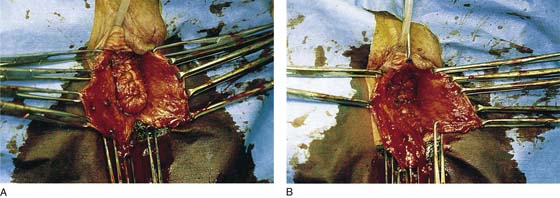

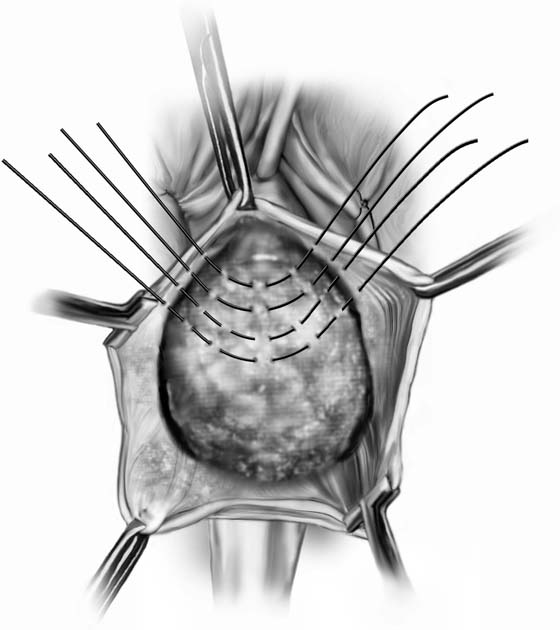

After an initial incision is made, usually Mayo or Metzenbaum scissors are inserted between the vaginal epithelium and the vaginal muscularis or between the layers of the vaginal muscularis and are gently forced upward while they are partially opened and closed (Fig. 54–8B). The vagina is then incised, and the incision is continued to the desirable level, as was previously discussed. As the vagina is incised, the edges are usually grasped with Allis or T clamps and are drawn laterally for further mobilization. Dissection of the vaginal flap is then accomplished by turning the clamps back across the forefinger and incising the vaginal muscularis with scissors or a scalpel (Fig. 54–9). An assistant maintains constant traction medially on the bladder wall itself or on the remaining vaginal muscularis and underlying vesicovaginal adventitia. The dissection is extended bilaterally until the entire cystocele has been dissected off the vaginal wall (Figs. 54–10 to 54–13). Dissection should be continued until lateral assessment of vaginal support can be fully evaluated. This requires dissection to the inferior pubic ramus on each side. At this point the presence or absence of a paravaginal defect should be easily demonstrated (see Fig. 54–10). It is also important to sharply dissect the base of the bladder off the apex of the vagina in posthysterectomy cases (see Fig. 54–11). In most cases, regardless of whether the patient suffers from urinary incontinence, plicating sutures at the urethrovesical junction should be placed to augment the posterior urethral support in the hope of preventing de novo postoperative stress incontinence. To obtain durable tissue that can be plicated across the undersurface of the proximal urethra, it is important to extend the dissection all the way to the periurethral attachment at the level of the inferior pubic ramus (see Figs. 54–12 and 54–13). Usually a glistening white plane is present all the way to this area of attachment. Figures 54–14 and 54–15 demonstrate the technique of bladder neck plication in conjunction with midline cystocele repair. After stitches for the bladder neck plication have been placed and tied (see Fig. 54–14), attention is directed to the prolapsed bladder base. The goal of the midline cystocele repair is to reduce and provide support to the prolapsed bladder, as well as to provide preferential support to the bladder neck. The surgeon should try to avoid complete flattening of the posterior urethrovesical angle because this, in theory, may create incontinence (see Fig. 54–15). In the standard anterior colporrhaphy, 2-0 delayed absorbable sutures are placed in the muscularis and adventitia of the vaginal wall. Depending on the severity of the prolapse, one or two rows of plication sutures or a purse string suture followed by plication sutures is placed. The author prefers, if at all possible, to place two layers of sutures. For the initial layer, a 2-0 absorbable suture is used; this is followed by a second layer of 2-0 permanent suture (Figs. 54–16 and 54–17). The vaginal epithelium is then trimmed (Fig. 54–18), and the anterior vaginal wall is closed with a continuous 3-0 absorbable suture (Fig. 54–19). Figures 54–14 and 54–20 demonstrate, in succession, the steps of midline cystocele repair.

FIGURE 54–9 A. Initial midline anterior vaginal wall incision. B. The incision is extended to the level of the proximal urethra. C. Sharp dissection and traction on the bladder facilitate dissection of the bladder off the vaginal wall. D. Mobilization of the cystocele off the vaginal wall is completed.

FIGURE 54–10 Dissection has been extended to the normal lateral attachment of the pubocervical fascia to the sidewall. Note that no paravaginal defect is present.

FIGURE 54–11 Dissection of the base of the bladder off the vaginal apex should be continued until the preperitoneal space is encountered.

FIGURE 54–12 Lateral dissection of the cystocele off the vagina is complete. Note that the base of the bladder is still adherent to the apex of the vagina.

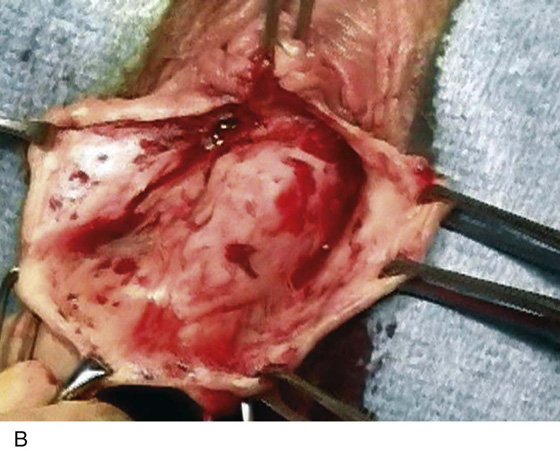

FIGURE 54–13 A and B. Two examples of cystoceles that have been completely mobilized off the vaginal epithelium.

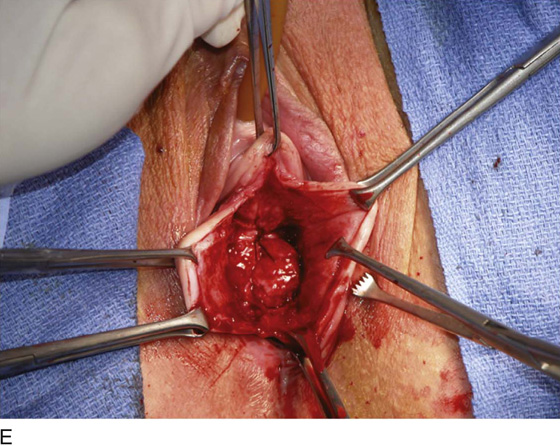

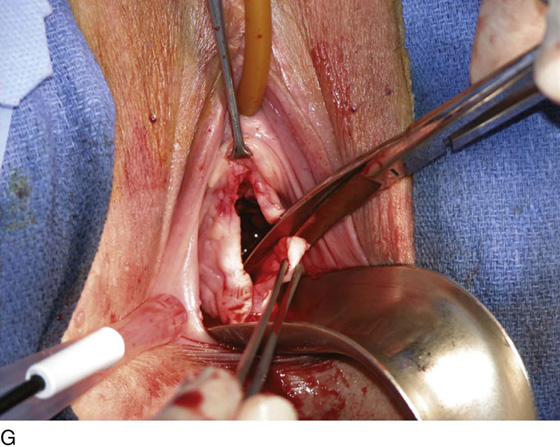

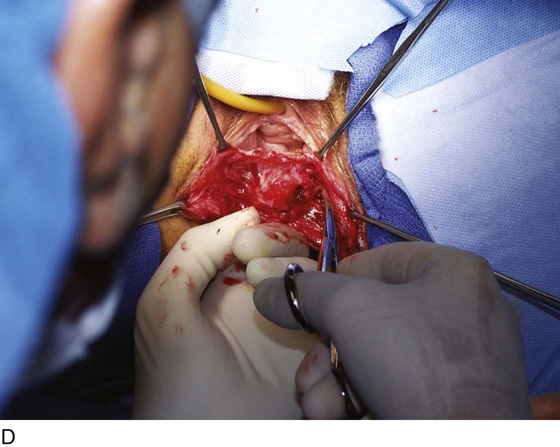

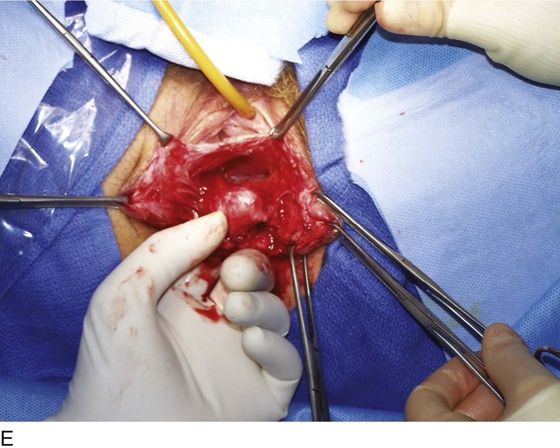

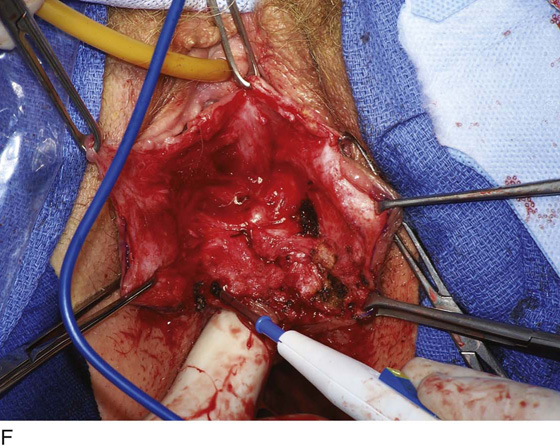

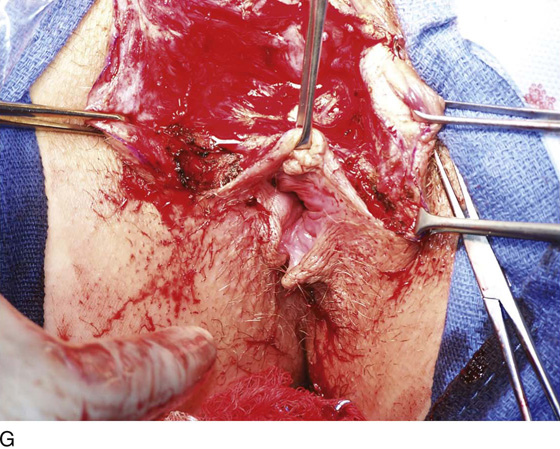

FIGURE 54–14 Anterior colporrhaphy with Kelly plication in a patient with an isolated midline cystocele and bladder neck mobility. A. Midline anterior vaginal wall incision is made after hydrodissection. B. Appropriate plane of dissection is demonstrated. C. Dissection has occurred lateral to the level of the inferior pubic ramus; shown here is the sharp dissection of the base of bladder off the apex of the vagina. D. The first plication stitch is being placed at the level of the bladder neck. E. The first stitch has been tied, providing preferential support to the proximal urethra and bladder neck (Kelly plication). F. Subsequent stitches have been placed, completing the anterior colporrhaphy. G. Excess mucosa is trimmed. H. The anterior vaginal wall is closed.

FIGURE 54–15 A. Kelly plication sutures have been placed and tied, plicating the pubocervical fascia across the midline at the level of the bladder neck. B. The bladder base has been plicated. Inset. Preferential support of the bladder neck compared with the bladder base. C. The bladder neck and the bladder base both have been plicated at the same level. Inset. Complete loss of the posterior urethrovesical angle. This should be avoided as it may lead to the development of de novo stress incontinence.

FIGURE 54–16 Bladder base plication sutures have been placed and tied.

FIGURE 54–17 A. The initial layer of sutures has been placed, plicating the cystocele. B. The second layer of plication sutures completes the cystocele repair.

FIGURE 54–18 Excess anterior vaginal wall epithelium is excised.

FIGURE 54–19 The anterior vaginal wall is closed with continuous or interrupted 3-0 absorbable sutures.

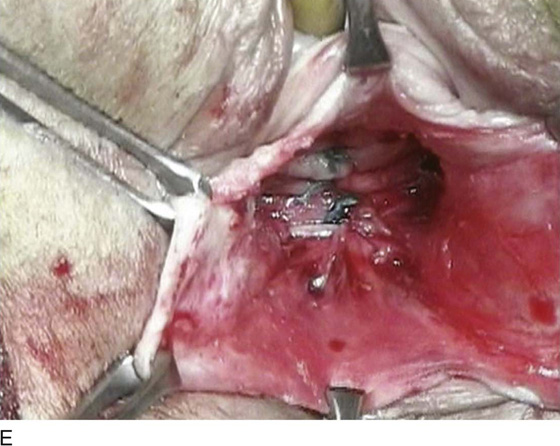

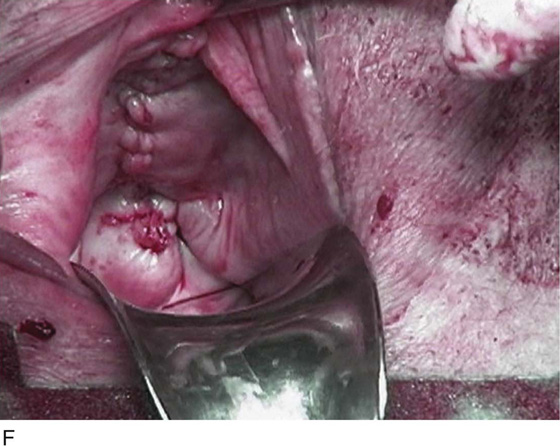

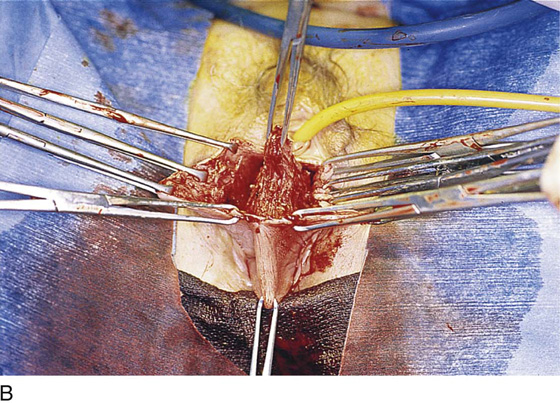

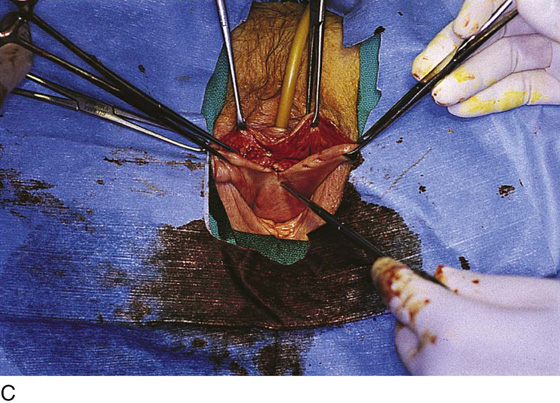

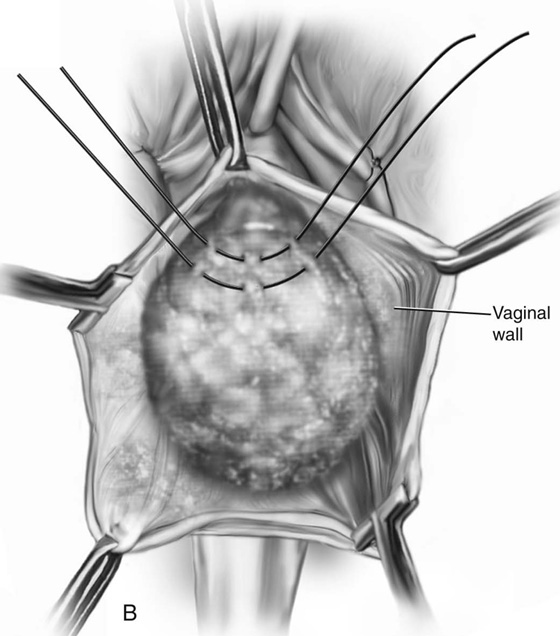

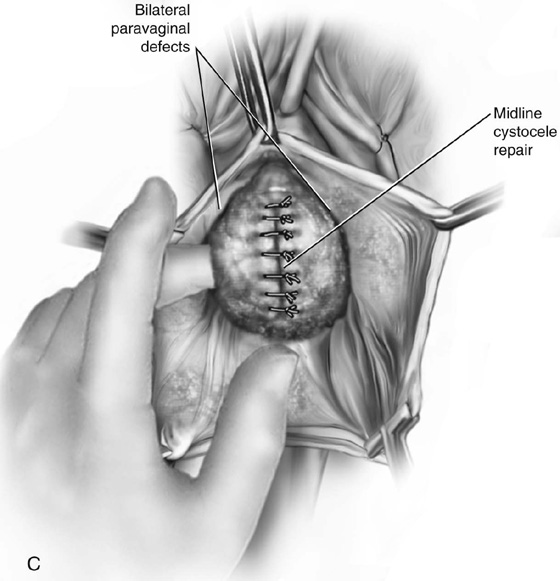

FIGURE 54–20 The technique of midline cystocele repair with Kelly plication. A. The anterior vaginal wall in this posthysterectomy patient is grasped with two Allis clamps, and a vasoconstrictive agent is injected to facilitate dissection in the appropriate plane. B. The anterior vaginal wall has been opened up, and dissection has been extended laterally on each side. Also, note that dissection must involve mobilizing the base of the bladder off the apex of the vagina. C. Dissection is extended to the inferior pubic ramus on each side. Note the good paravaginal attachment, ruling out any paravaginal defect in this patient. D. The midline cystocele has been initially plicated with delayed absorbable suture. Note: Plication sutures have been placed at the proximal urethral bladder neck to provide preferential support over those placed over the base of the bladder. E. Dissection has been extended farther laterally to facilitate the development of more fascia, and a second layer of permanent sutures is now used to complete the midline cystocele plication. F. After the anterior vaginal wall is trimmed, the anterior vaginal wall is closed with a 3-0 delayed absorbable suture. Note the excellent support of the anterior segment in the midline with maintenance of good lateral vaginal sulci on each side.

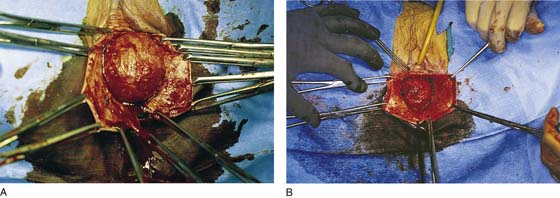

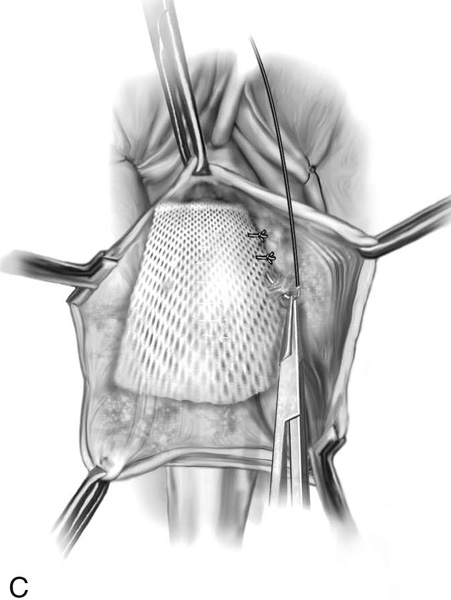

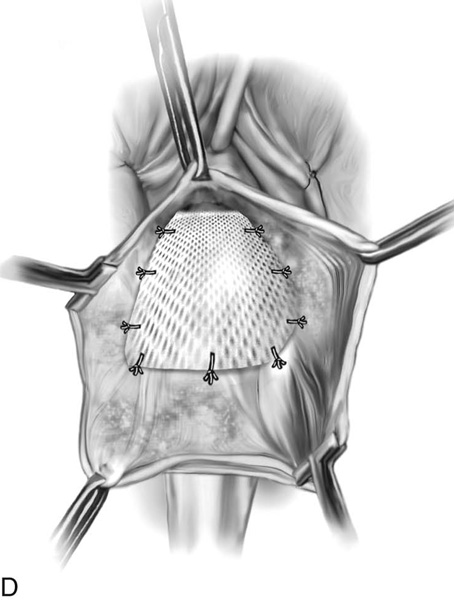

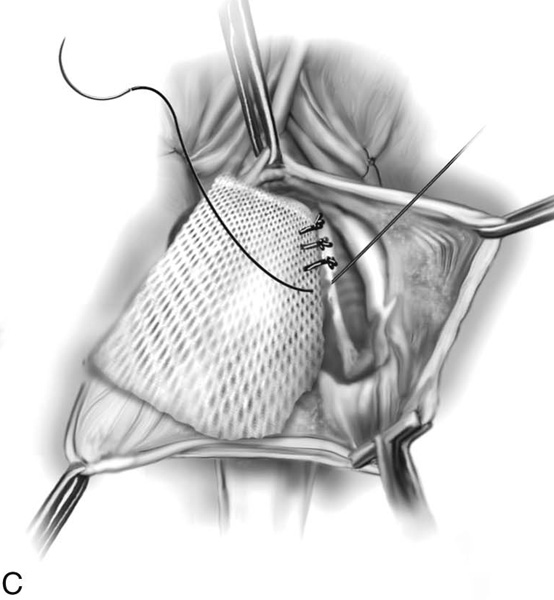

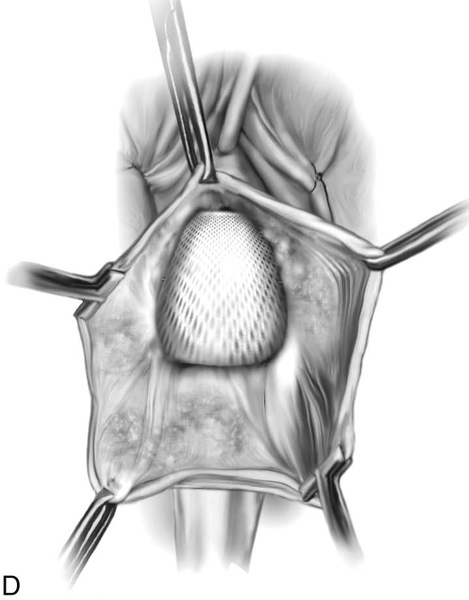

Some surgeons prefer to augment anterior vaginal wall repair with a free graft of tissue or mesh, which can be biologic or synthetic. The mesh or tissue is placed over the stitches and is anchored in place at the lateral limit of the previous dissection or at the inside of the anterior vaginal wall (Figs. 54–21 and 54–22). If bilateral paravaginal defects are present, the material can be attached to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis on each side (Fig. 54–23). Materials that have been utilized have included rectus abdominis, fascia lata, and cadaveric fascia lata, as well as synthetic mesh such as Marlex, Mersilene, or Prolene. Indications for mesh-augmented prolapse repairs remain very controversial. Some surgeons believe that repairs should be augmented in recurrent cases and in women with a very poor or little muscular component to their vaginal skin, which is usually secondary to long-standing urogenital atrophy (Fig. 54–24).

At times a cystocele coexists with an enterocele (Fig. 54–25A). In this situation it is important to dissect out the individual defects, thus completely mobilizing the enterocele sac from the cystocele. Each defect is then individually repaired, and, if indicated, the vaginal vault is suspended (see Fig. 54–25).

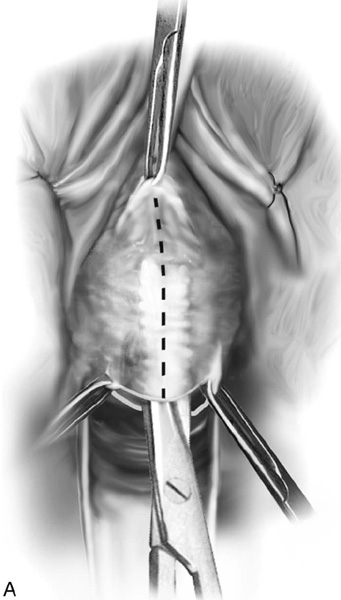

Vaginal Paravaginal Repair

The objective of a paravaginal defect repair for anterior vaginal wall prolapse is to reattach the detached lateral vagina to its normal place of attachment at the level of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (white line). This can be accomplished by using a vaginal or retropubic approach. Although at times a paravaginal defect can be accurately diagnosed preoperatively, many times it is an intraoperative diagnosis. To diagnose this defect via a transvaginal route, one must extend the plane of dissection between the vagina and the bladder all the way out to the inferior pubic ramus. When this lateral area is reached, the attachment must be assessed subjectively. At times complete detachment will be obvious, meaning that lateral dissection will lead directly into the retropubic space, and retropubic fat will be visualized. At times there will be an attachment, albeit a very weak one, and the decision must be made whether to completely detach the tissue, so it can be reattached in appropriate fashion. To perform a true vaginal paravaginal repair, there must be digital access into the retropubic space. The most important landmark is palpation of the ischial spine via the anterior segment. Once this is palpated, one can usually palpate the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis moving along the lateral pelvic sidewall toward the back of the symphysis.

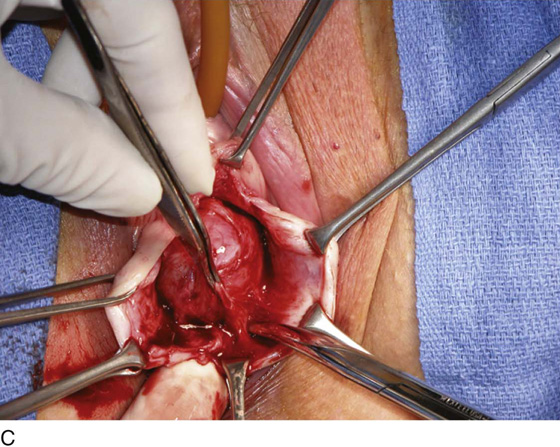

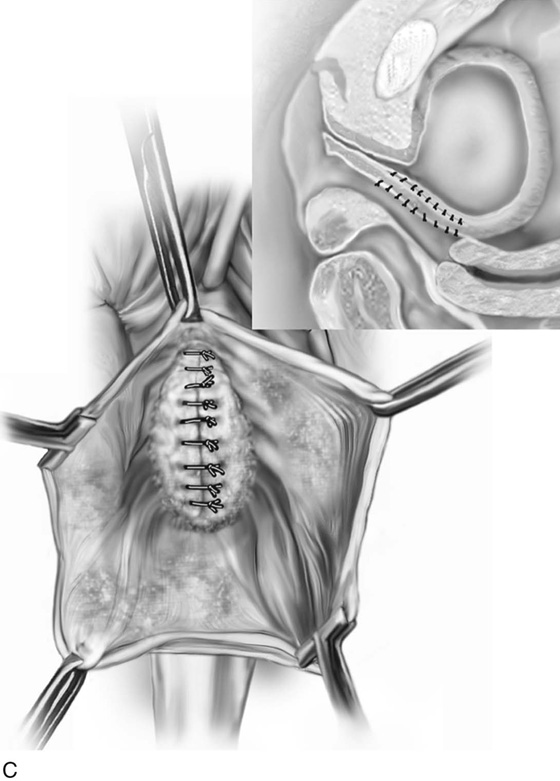

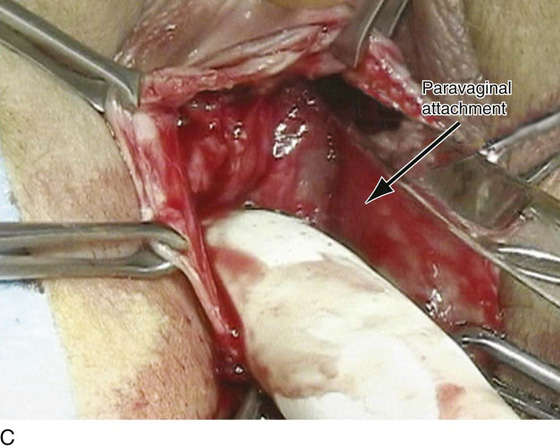

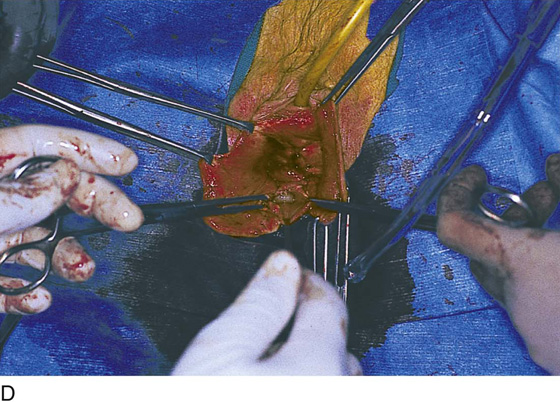

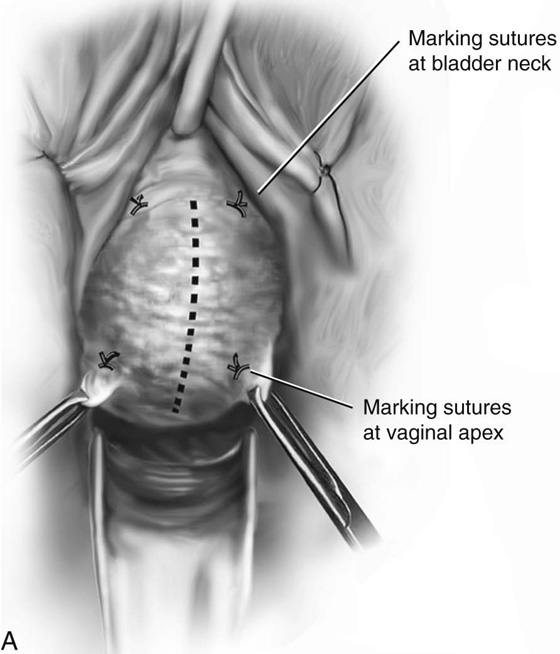

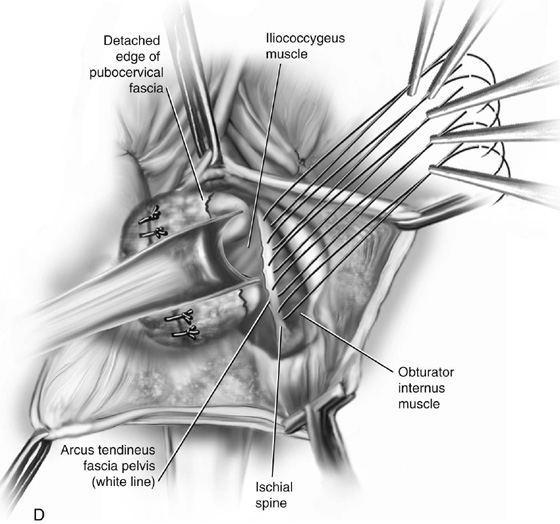

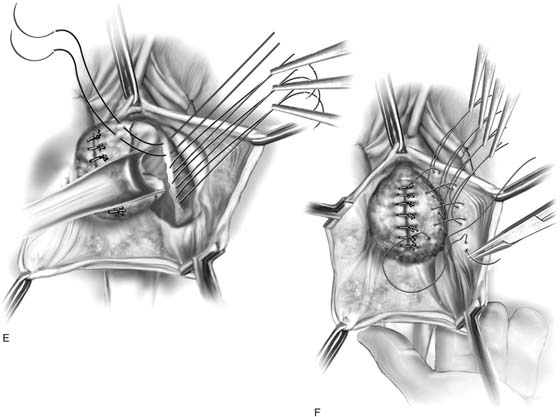

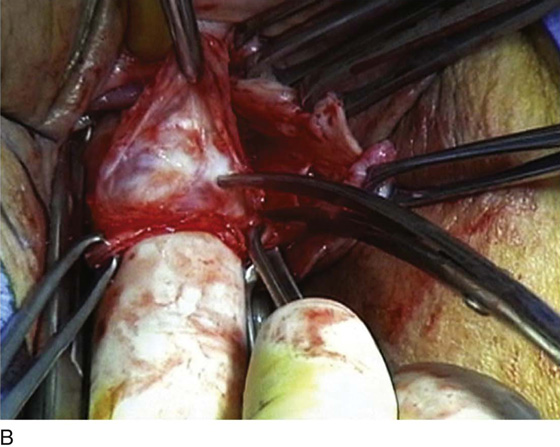

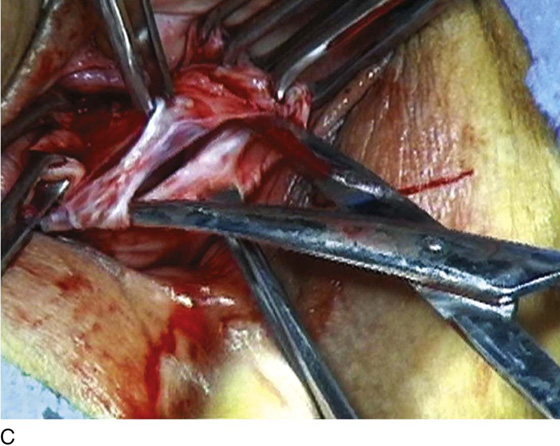

Preparation for vaginal paravaginal repair begins as for an anterior colporrhaphy. Marking sutures are placed on the anterior vaginal wall or each side of the urethrovesical junction (identified by placing gentle traction on the catheter), and at the vaginal apex. If a culdoplasty is being performed, the sutures are placed but not tied until completion of the paravaginal repair and closure of the anterior vaginal wall. As for anterior colporrhaphy, vaginal flaps are developed by incising the vagina in the midline and dissecting the vaginal muscularis laterally. The dissection is performed bilaterally until the space is developed between vaginal wall and retropubic space. Blunt dissection with the surgeon’s index finger is used to extend this space anteriorly along the pubic ramus, medially to the pubic symphysis, and laterally toward the ischial spine. If the defect is present and dissection is occurring in the appropriate place, one should easily enter the retropubic space, visualizing retropubic fat. The ischial spine then can be palpated on each side. The arcus tendineus fascia pelvis coming off the spine can be followed to the back of the symphysis. After dissection is complete, midline plication of the vaginal muscularis can be performed at this point or after placement and tying of the paravaginal sutures. On the lateral pelvic sidewall, the obturator internus muscle and the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis are identified by palpation and then by visualization. Retraction of the bladder and the urethra medially is best accomplished with a Breisky-Navratil retractor, and posterior retraction is provided with a lighted suction device. With 0 nonabsorbable suture, the first stitch is placed through the white line just anterior to the ischial spine. If the white line is not visualized, is detached from the pelvic sidewall, or clinically is not thought to be durable, then the suture should be passed into the fascia overlying the obturator internus muscle. Placement of subsequent sutures is facilitated by placing tension on the first suture. A series of four to six sutures are placed and held, working anteriorly along the white line to the level of the urethrovesical junction. Starting with the most anterior suture, the surgeon picks up the edge of the periurethral tissue (vaginal muscularis or pubocervical fascia) at the level of the urethrovesical junction and then tissue from the undersurface of the vaginal flap at the previously marked site. Subsequent sutures move posteriorly until the last stitch closest to the ischial spine is attached to the undersurface of the vagina at the site of the marking sutures placed at the vaginal apex. Stitches in the vaginal wall must be carefully placed to allow adequate tissue for subsequent midline vaginal closure. After all stitches are placed on one side, the same procedure is carried out on the other side. The stitches are then tied in order from the urethra to the apex, alternating from one side to the other. This repair is a three-point closure between the vaginal epithelium, vaginal muscularis and endopelvic fascia (pubocervical fascia), and lateral pelvic sidewall at the level of the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Tissue-to-tissue approximation is necessary between these structures. Suture bridges must be avoided by careful planning of suture placement. Vaginal tissue should not be trimmed until all stitches are tied. As was previously stated, if not already performed, vaginal muscularis can then be plicated in the midline if necessary with several interrupted sutures. The vaginal flaps are then trimmed and closed with a running delayed absorbable suture. Figure 54–26 illustrates the entire procedure of a three-point vaginal paravaginal repair in a stepwise fashion. Other techniques can also be utilized to address a paravaginal defect. Some surgeons believe it is not necessary to include the inside of the vaginal wall in a vaginal paravaginal repair. This then becomes a two-point closure in which the detached fascia is sutured directly into the white line or the fascia over the obturator internus muscle (Figs. 54–27 and 54–28). If paravaginal support simply needs to be strengthened, or if the surgeon does not desire to fully enter the retropubic space to expose the arcus, a modified two-point closure in which the fascia is sutured to the upper part of the anterior vaginal wall can be performed (Fig. 54–29). This technique strengthens lateral support of the bladder but does not re-create the normal lateral vaginal sulcus because the fascia and the vagina are not reattached to the white line or the obturator internus fascia. Some surgeons routinely include the inside lining of the vaginal wall during traditional anterior colporrhaphy (Fig. 54–30). Although this will close off any paravaginal defect, it will commonly result in a scarred, foreshortened anterior segment.

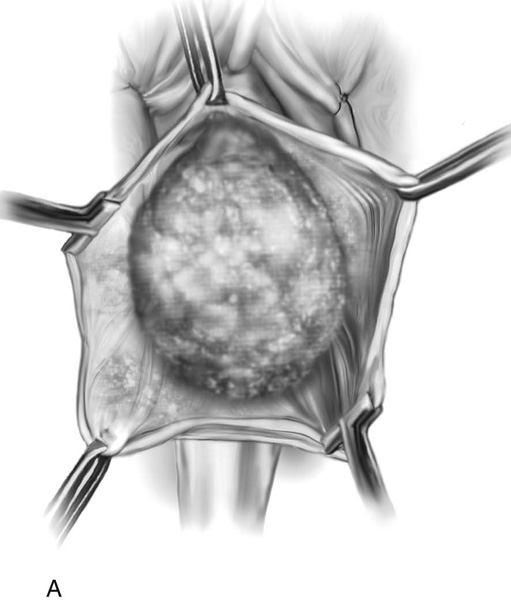

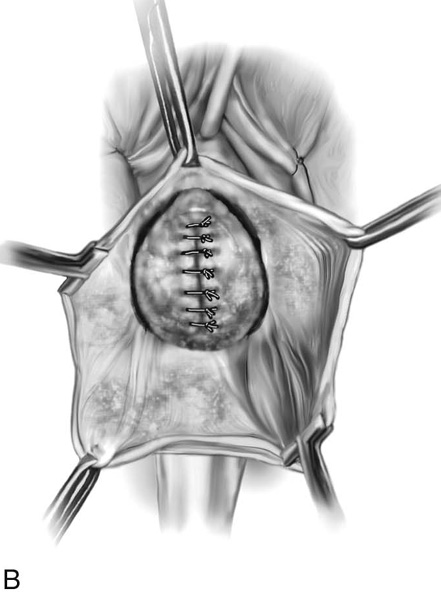

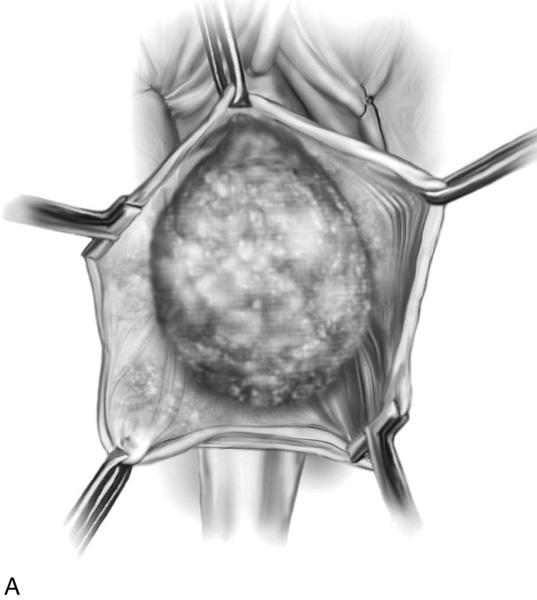

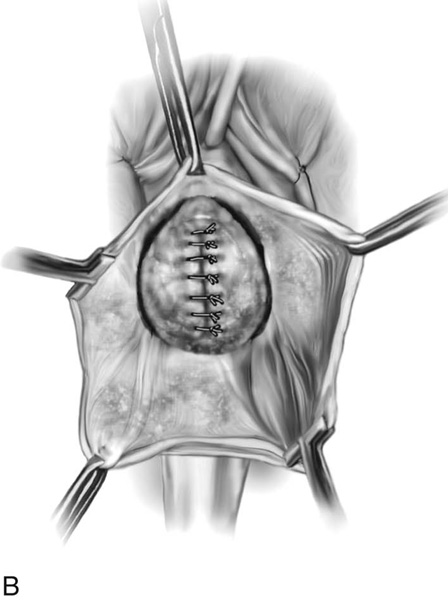

FIGURE 54–21 Technique of placement of mesh in the anterior vaginal wall. A. The cystocele has been completely mobilized from the anterior vaginal wall. B. The cystocele has been plicated in the midline. C. The mesh is fixed to the upper portion of the anterior vaginal wall on the left. D. Fixation of the mesh is completed by fixing it to the opposite side, as well as to the inside lining of the vaginal wall at the level of the vaginal apex.

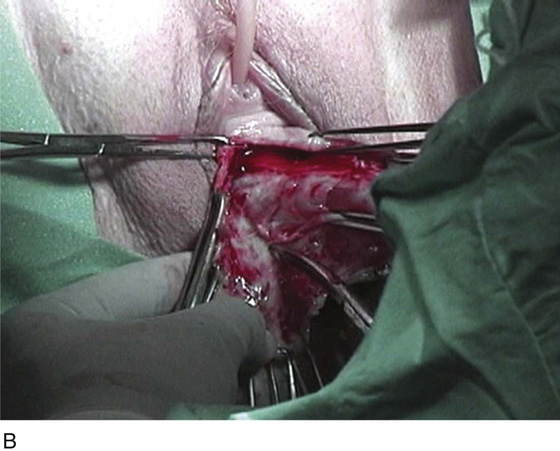

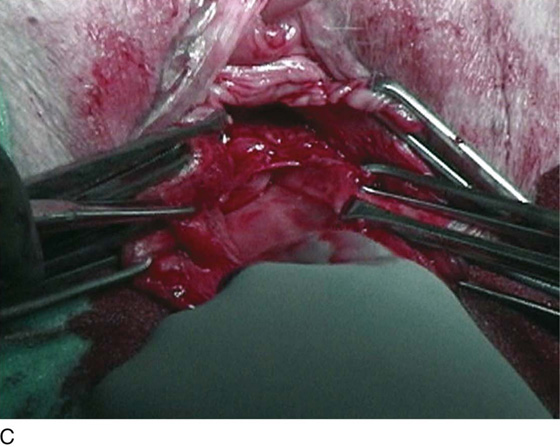

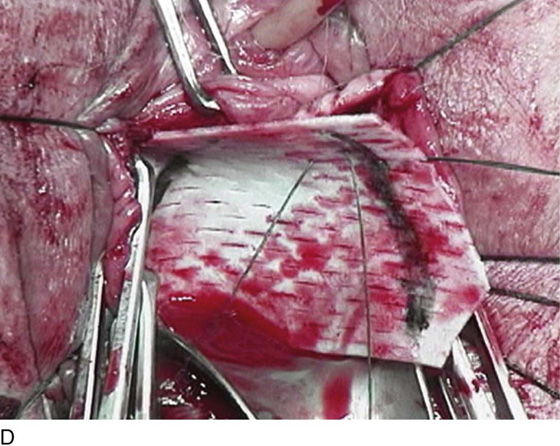

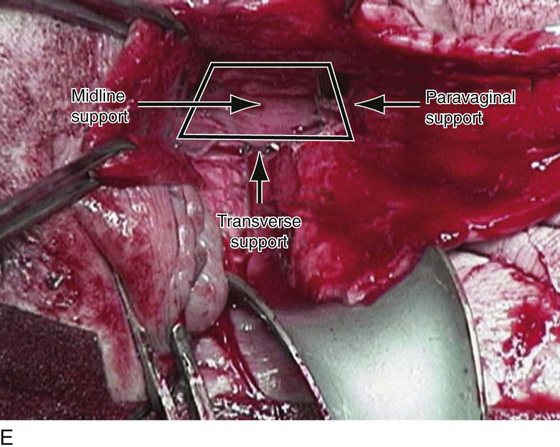

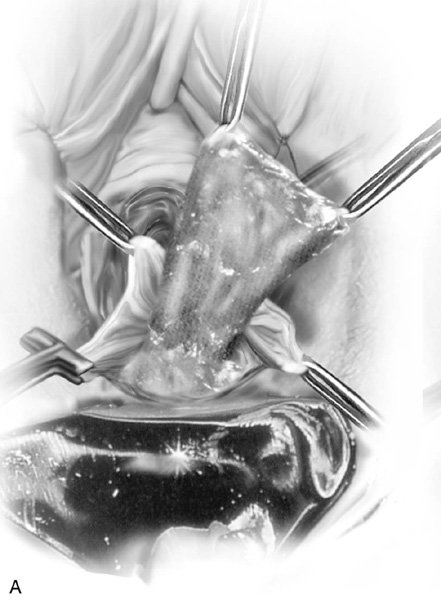

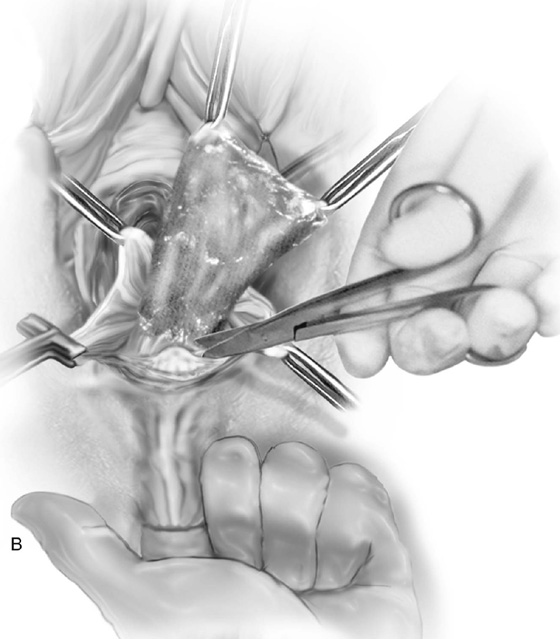

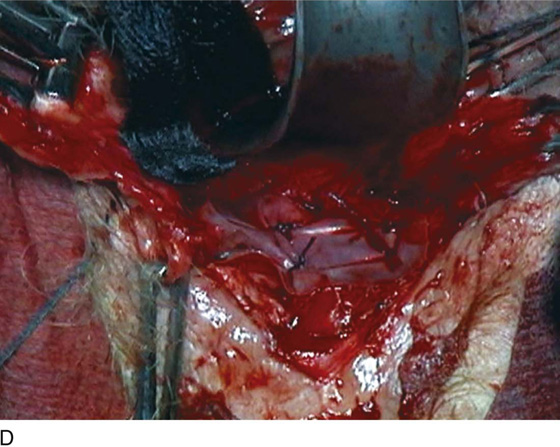

FIGURE 54–22 Technique of a mesh-augmented anterior colporrhaphy in a patient with a recurrent cystocele and enterocele. A. The anterior vaginal wall is grasped with two Allis clamps and injected. B. Sharp dissection of the bladder from the anterior vaginal wall. C. An initial plication has been performed to reduce the cystocele. Note that the enterocele sac has been identified and entered. D. A trapezoid piece of Pelvisoft (Bard Urologic, Covington, Ga) is being fixed to the upper portion of the anterior vaginal wall on the left side. E. The mesh is fixed in place in the anterior segment; the trapezoid concept is demonstrated, showing how the mesh creates paravaginal, midline, and transverse support. F. The anterior vaginal wall has been trimmed and closed, and the vaginal vault has been suspended. Note the good support of the entire anterior segment.

FIGURE 54–23 Technique of utilizing a mesh to correct bilateral paravaginal defects. A. The cystocele has been dissected from the anterior vaginal wall. B. Midline plication has been created, and bilateral paravaginal defects are seen. C. The mesh is sutured directly to the arcus with interrupted sutures. D. The completed mesh repair shows the mesh fixed bilaterally to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis.

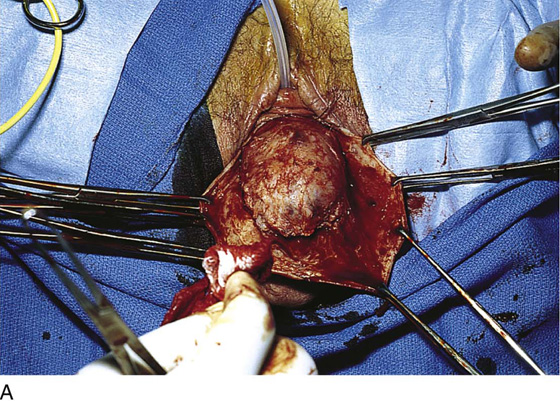

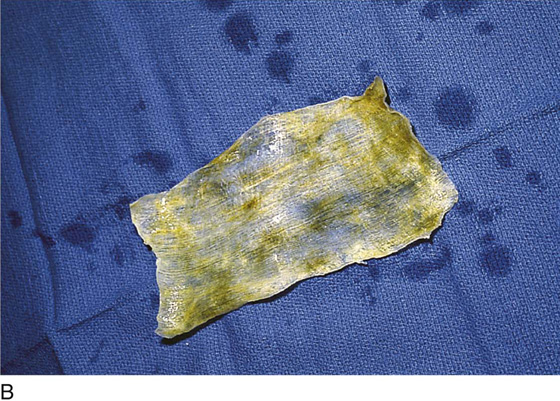

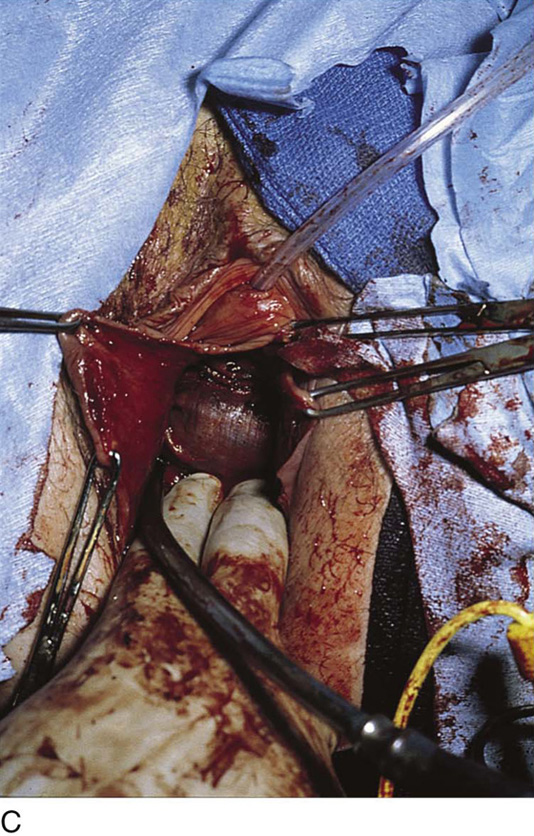

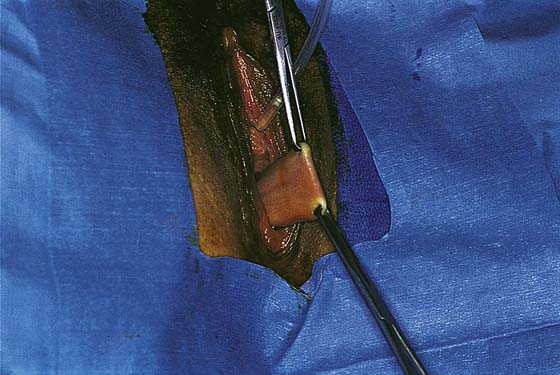

FIGURE 54–24 A. A large cystocele has been dissected off the vaginal epithelium. Note the minimal fascia present on the prolapsed bladder base. B. A piece of cadaveric fascia lata. C. The fascia has been attached to the inner aspect of the anterior vaginal wall, reducing the prolapsed bladder base.

FIGURE 54–25 Combined cystocele and enterocele repair A. Cystocele in conjunction with vaginal vault prolapse. B. An anterior vaginal wall incision has been made, and the anatomic location of the bladder base is noted. C. The vaginal incision is extended over the suspected enterocele. D. The bladder base prolapse has been plicated, the enterocele sac has been mobilized off the bladder base, and the peritoneal sac has been opened.

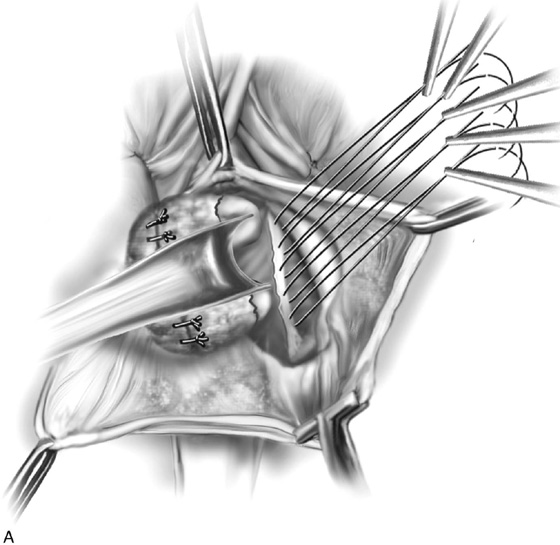

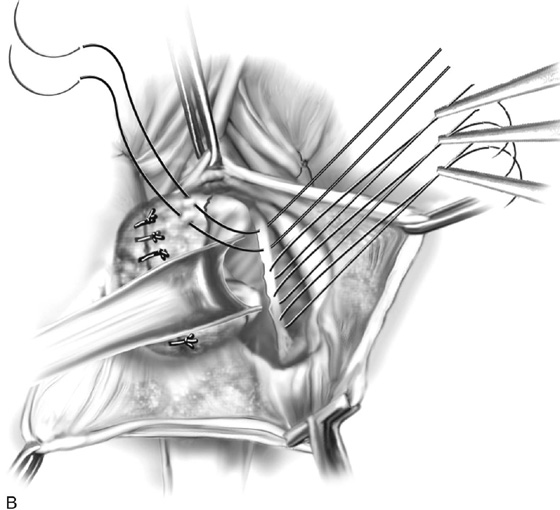

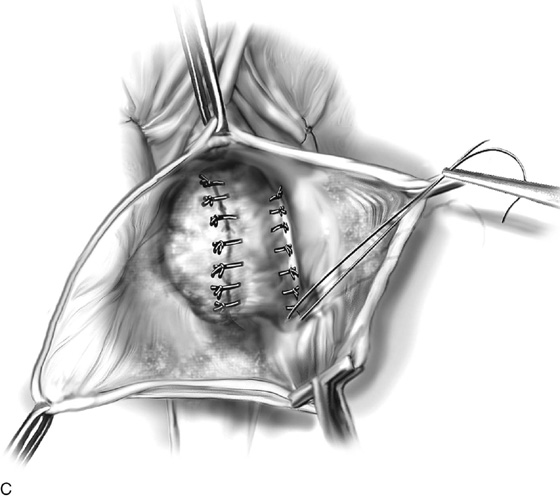

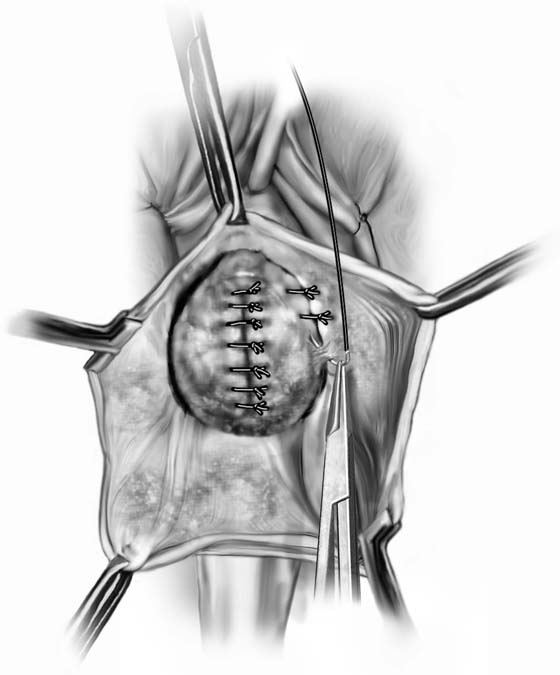

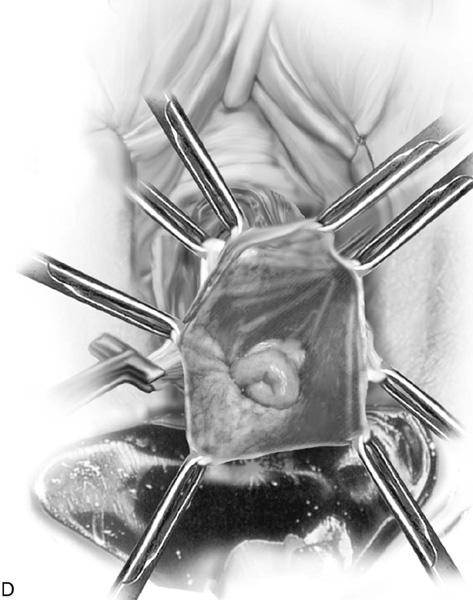

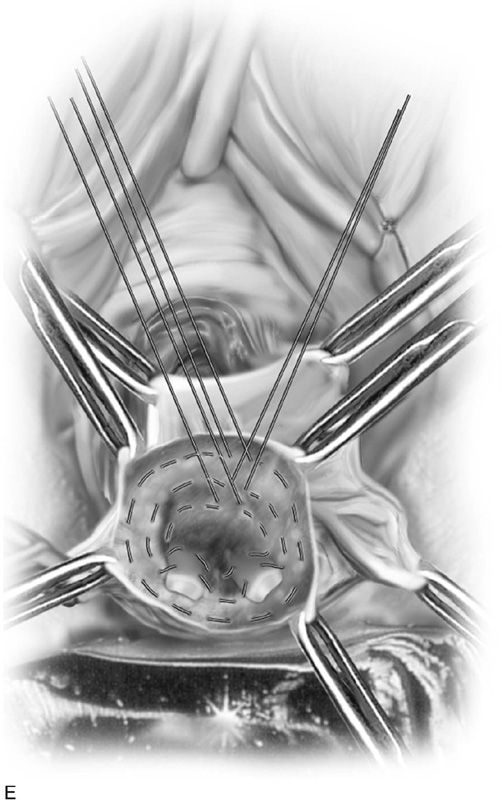

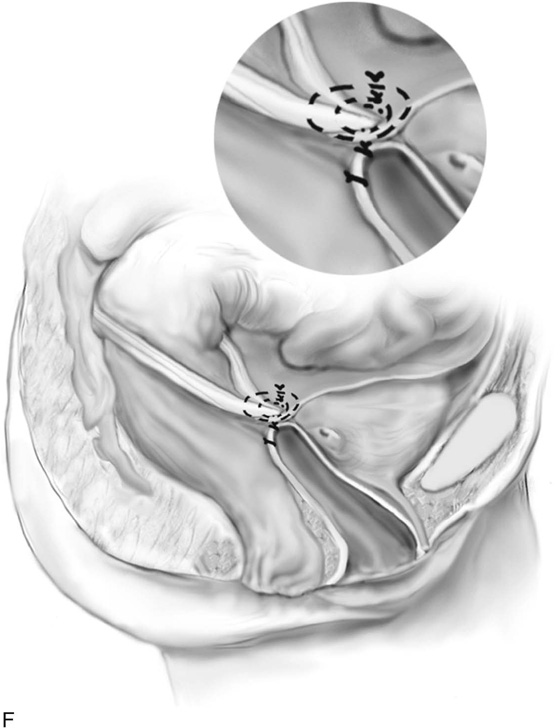

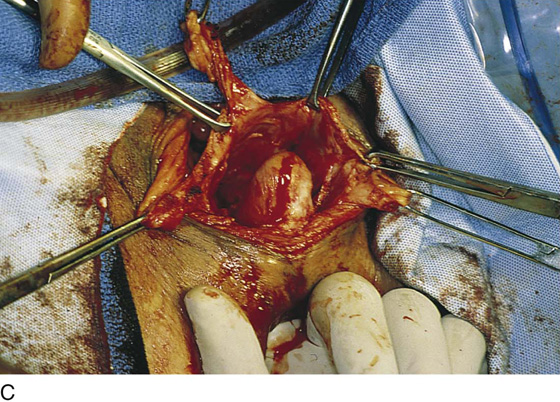

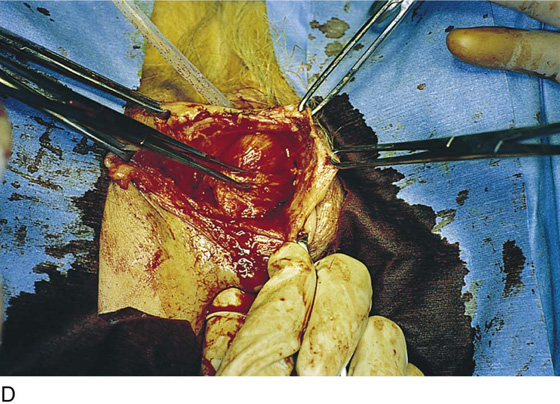

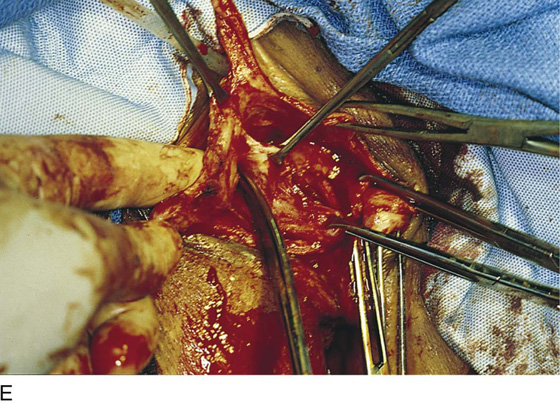

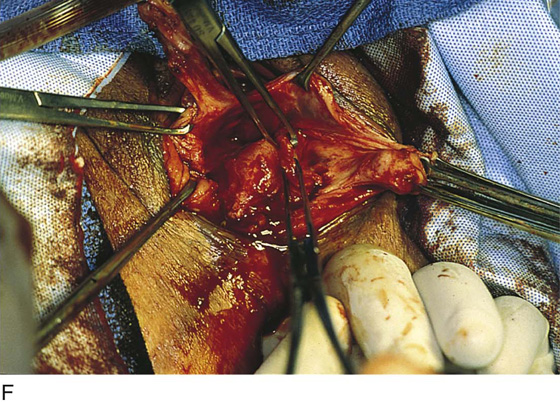

FIGURE 54–26 Technique of vaginal paravaginal repair. A. Marking sutures are placed at the bladder neck and vaginal apex. A midline anterior vaginal wall incision is made. B. The bladder is dissected laterally and off the vaginal apex. Midline plication is performed. C. Midline plication is completed; obvious bilateral paravaginal defects are present. D. The bladder is retracted medially, and numerous sutures are passed through the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis (white line). E. Sutures are then passed through the detached pubocervical or endopelvic fascia. F. Sutures are passed through the inside of the vaginal wall, thus completing the three-point closure.

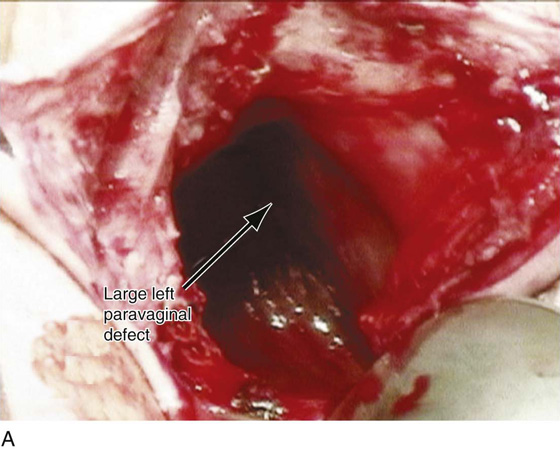

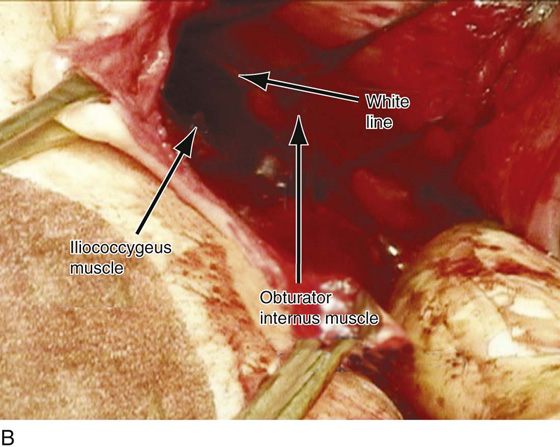

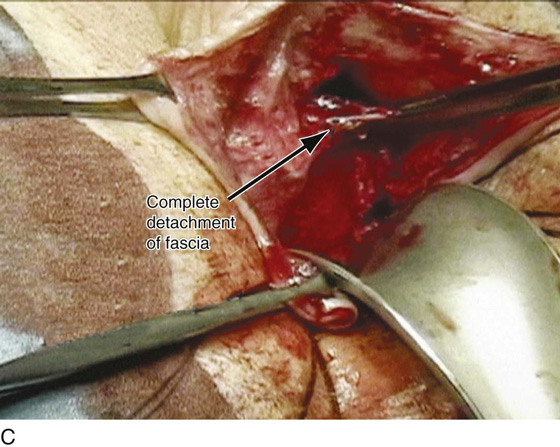

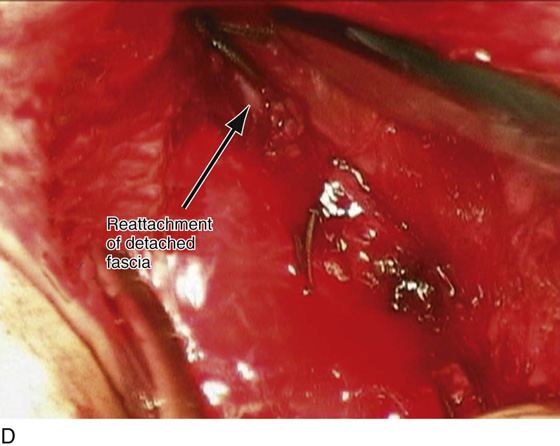

FIGURE 54–27 Technique of two-point vaginal-paravaginal repair. A. Large paravaginal defect on the left side. B. Sutures have been passed through the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis on the left side. The obturator internus muscle and the iliococcygeus muscle, respectively, are seen above and below the white line. C. The detached fascia is noted. D. The detached fascia has been sutured into the arcus with numerous interrupted, permanent sutures.

FIGURE 54–28 Technique of two-point paravaginal defect repair, in which the detached fascia is sutured directly into the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, or the white line. Note, in contrast to the three-point closure, the inside of the vaginal wall is not included in this repair.

FIGURE 54–29 Technique of two-point vaginal-paravaginal repair where the lateral edge of the detached fascia is sutured into the upper part of the anterior vaginal wall. Note that this technique does not require complete entrance into the retropubic space or visualization and identification of the obturator internus fascia and the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis.

FIGURE 54–30 Technique of simple anterior colporrhaphy in which the inside of the anterior vaginal wall is included in the plication stitches. Note that this technique will not restore any anterolateral vaginal sulcus and may result in a foreshortened and scarred anterior vaginal segment.

Posterior Vaginal Wall Defects

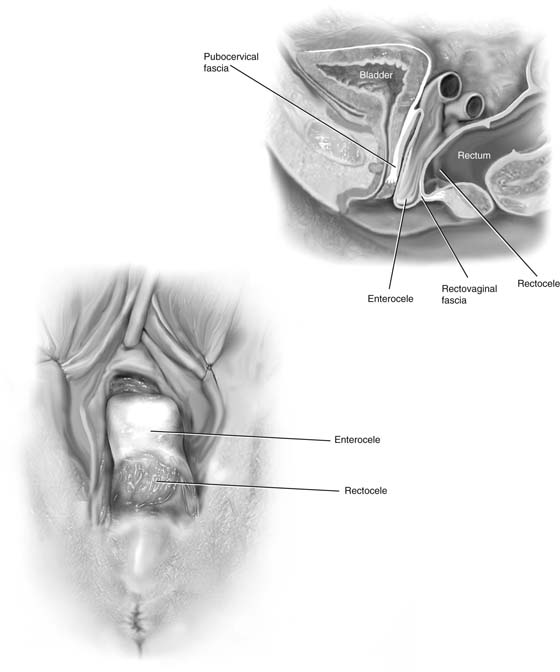

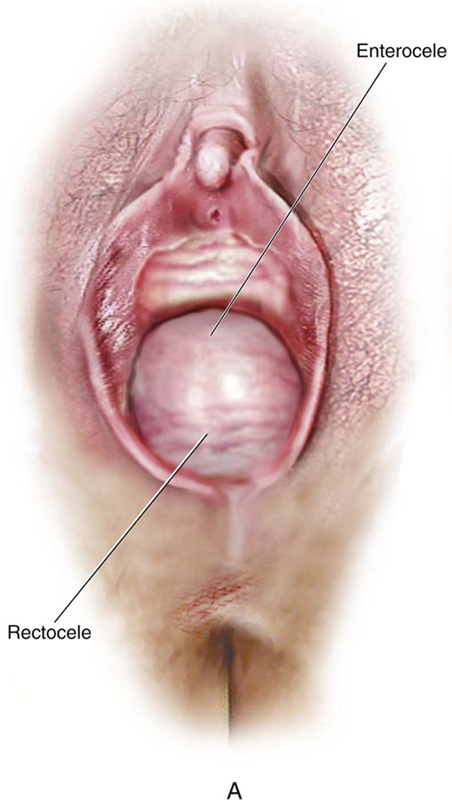

Posterior vaginal wall defects can be due to an enterocele, a rectocele, or, very commonly, a combination of both. These defects are commonly associated with varying degrees of vaginal vault prolapsed, as well as anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

Vaginal Enterocele Repair

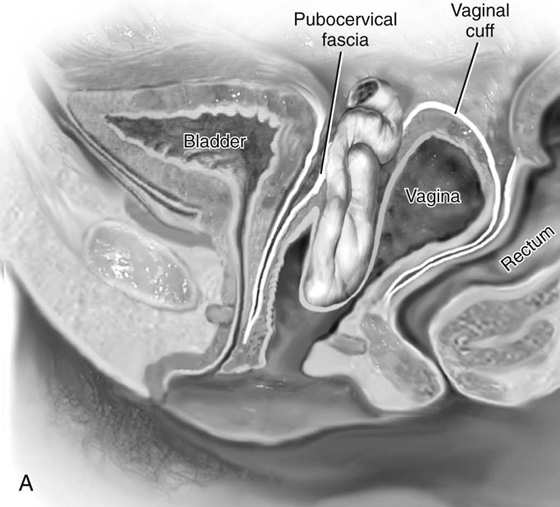

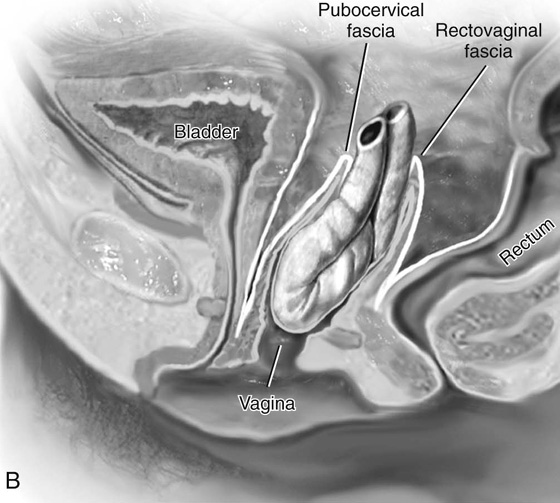

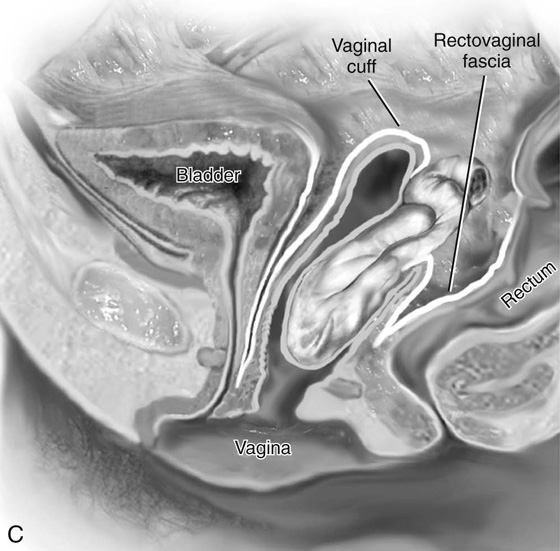

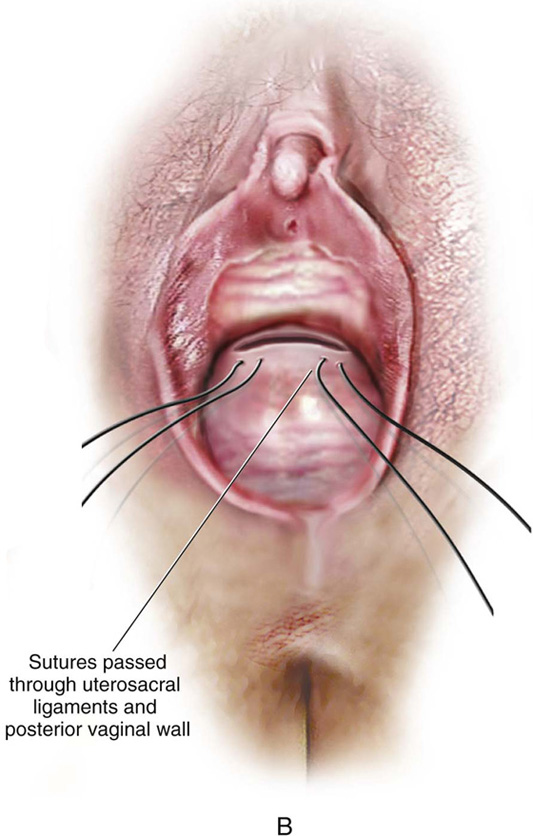

Until recently, the anatomy of the cul-de-sac and its relationship to enterocele formation were poorly understood. After hysterectomy, the vaginal apex should be suspended or reattached to the cardinal and uterosacral ligaments. Enteroceles develop as the pubocervical and rectovaginal fasciae separate, allowing a peritoneal sac with its contents to protrude through the fascial defect (Fig. 54–31). Thus, by definition, an enterocele occurs when the peritoneum comes into direct contact with the vaginal epithelium with no intervening fascia. In a woman whose uterus is intact, enteroceles commonly occur posterior to the cervix and anterior to the rectum. Following hysterectomy, enteroceles may occur anterior to the vaginal apex, at the vaginal apex, or posterior to the vaginal apex. In apical enteroceles, the pubocervical fascia anteriorly and the rectovaginal fascia posteriorly separate at the apex. An anterior enterocele is a rare defect in the support of the transverse portion of the pubocervical fascia to the apex of the vagina and should not be confused with a cystocele. The peritoneal sac along with its intra-abdominal contents herniates anterior to the apex and posterior to the base of the bladder. A posterior enterocele is a defect at the superior or transverse portion of the rectovaginal fascia in which the peritoneal sac, with its intra-abdominal contents, herniates anterior to the rectum but posterior to the vaginal apex.

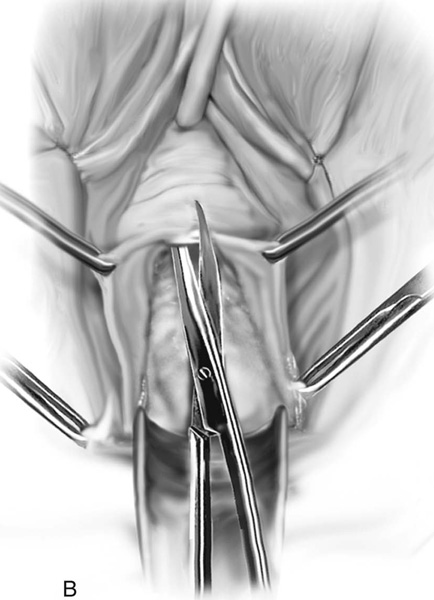

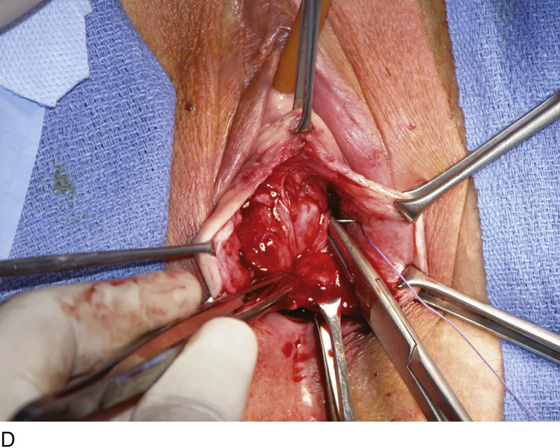

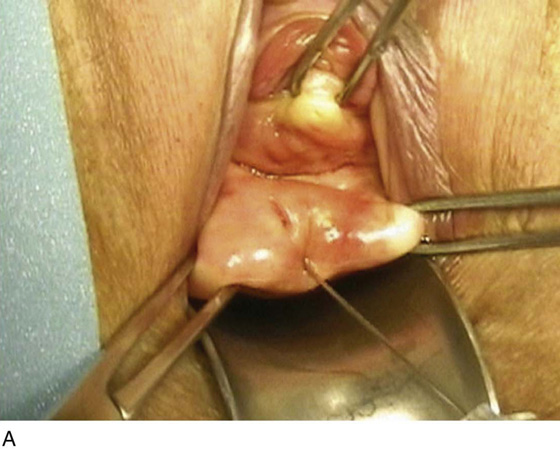

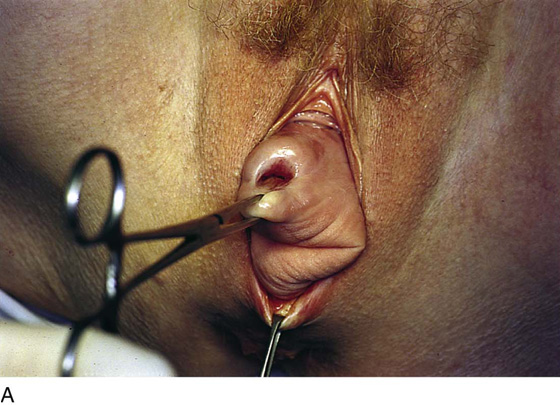

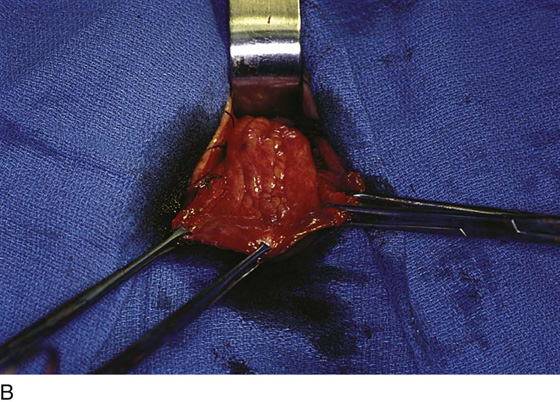

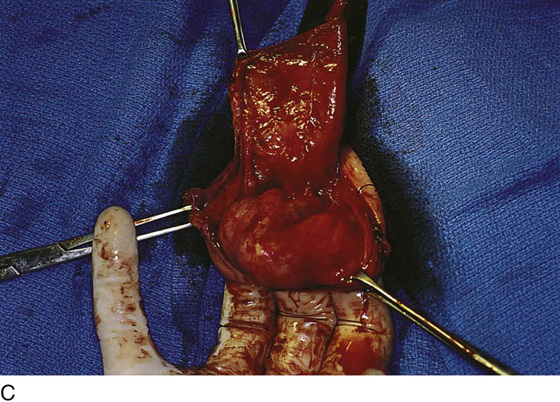

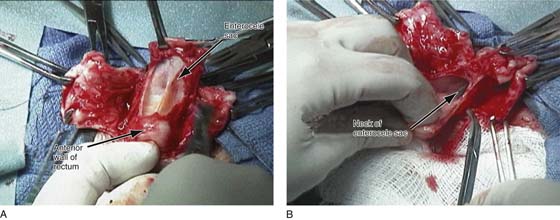

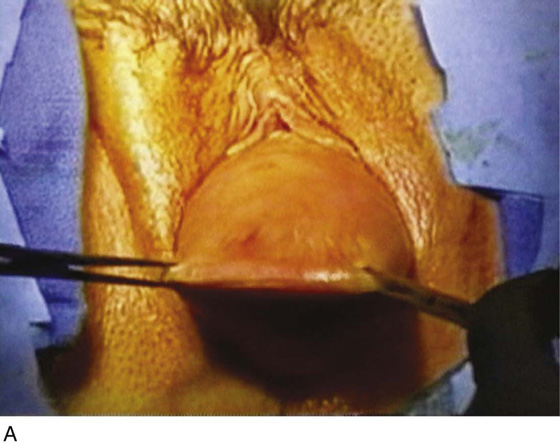

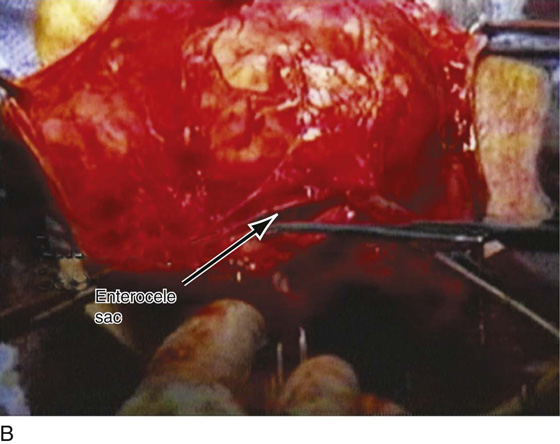

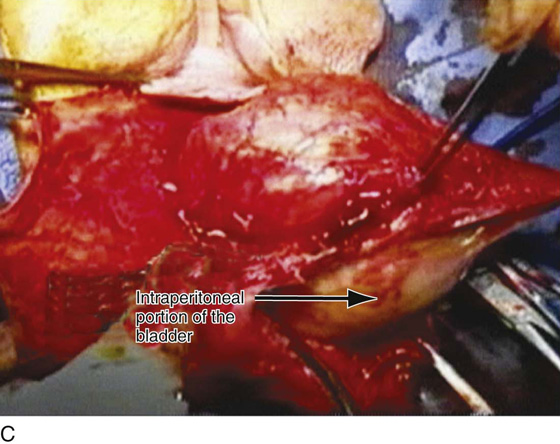

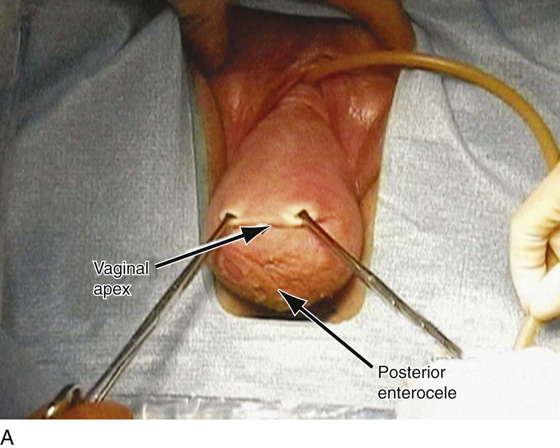

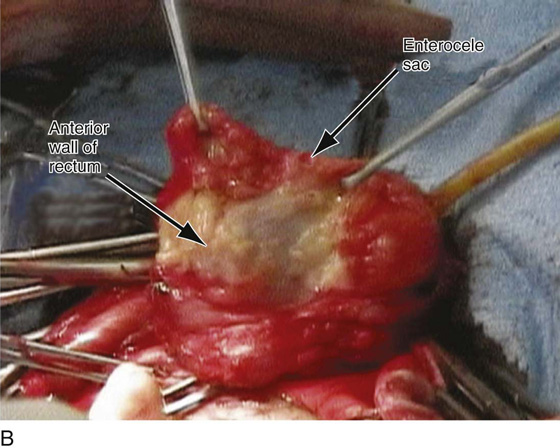

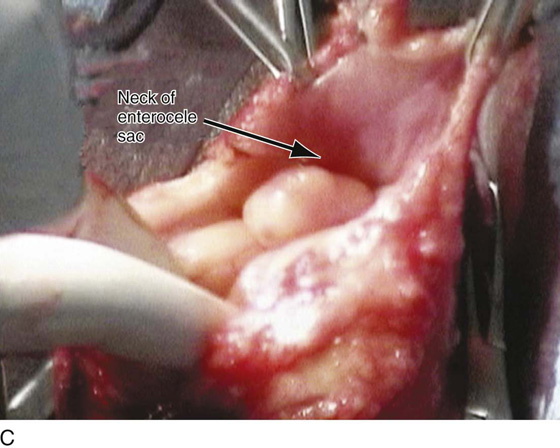

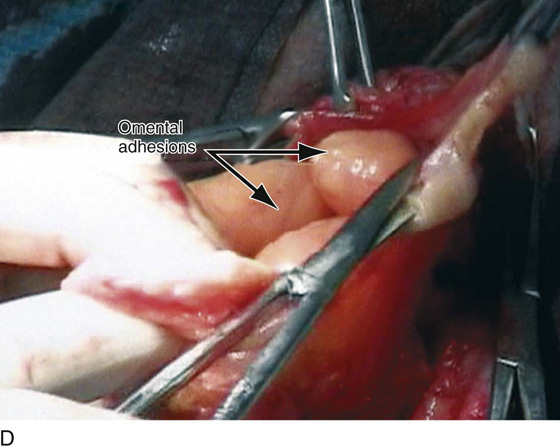

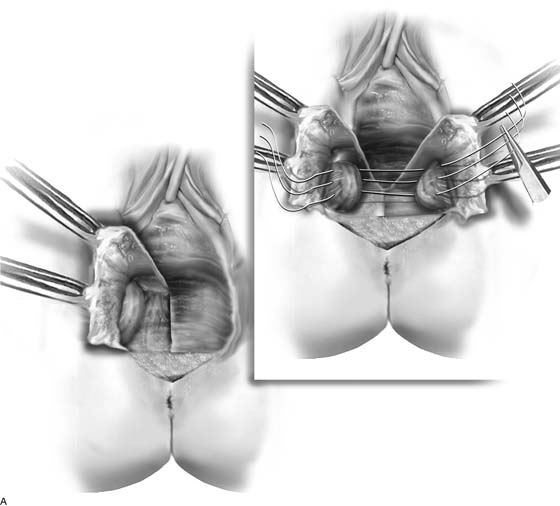

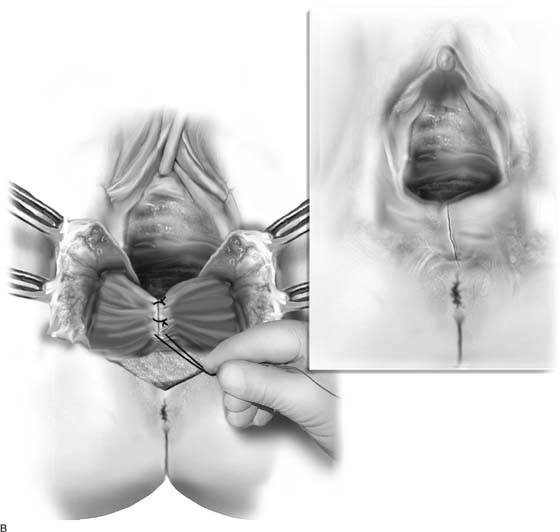

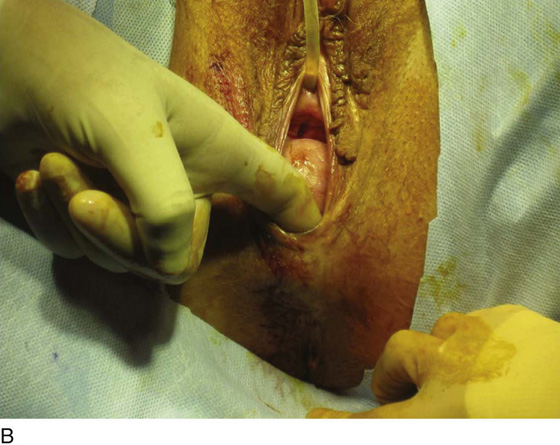

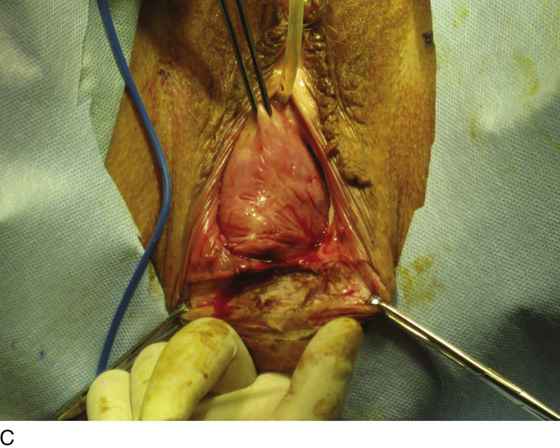

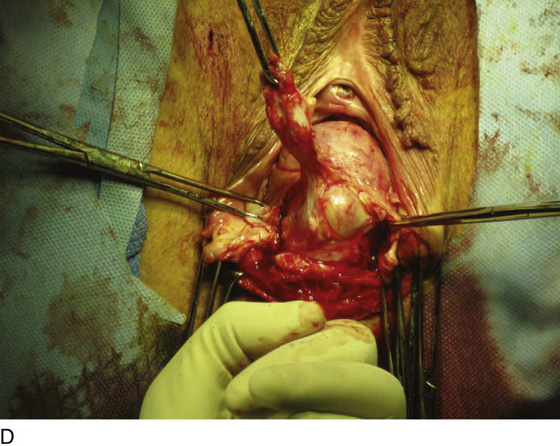

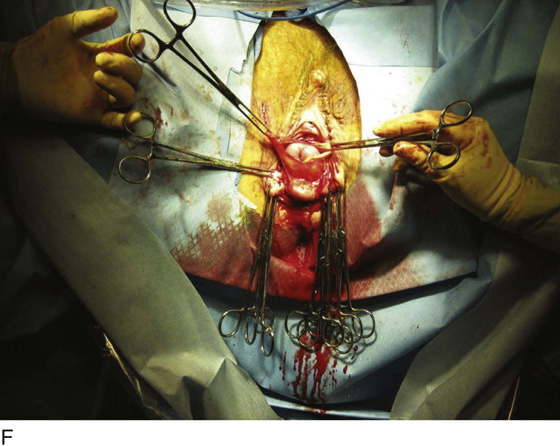

Because an enterocele is a true hernia, it is best repaired by identification of the fascial defect, dissection and excision of the peritoneal sac, reduction of intra-abdominal contents, and closure of the defect. The technique of vaginal enterocele repair involves placing the patient in the dorsal lithotomy position. The bladder should be drained before the first incision. The vagina over the enterocele is grasped with Allis clamps, and the boundaries of the defect are visualized (Figs. 54–32 and 54–33A). A midline incision is made through the vaginal epithelium over the enterocele (see Fig. 54–33A). The vaginal epithelium is dissected sharply away from the enterocele sac, and the sac is completely mobilized all the way up to its neck (Figs. 54–33 through 54–36). This may involve mobilization of the hernia off the urinary bladder (Fig. 54–37), as well as mobilization of the peritoneal sac off the anterior rectal wall (Figs. 54–36 and 54–38). When an enterocele sac is difficult to distinguish from the rectum, differentiation is aided by a rectal examination with simultaneous dissection of the enterocele sac off the anterior rectal wall (see Figs. 54–36A and 54–38B). At times, distinguishing the enterocele sac from a large cystocele may prove difficult (see Fig. 54–40). In this situation, placement of a probe into the bladder or transillumination with a cystoscope may prove helpful. After the enterocele sac has been dissected from the vagina and the rectum, traction is placed on it with two Allis clamps, and the sac is sharply entered (see Figs. 54–36B, 54–37C, 54–38C, 54–39C). The enterocele sac is explored digitally to ensure that no small bowel or omental adhesions are present. The method of closure of the defect depends on whether a vaginal vault suspension procedure is indicated and, if so, what type is to be performed. If adequate vaginal length exists and no suspension procedure is necessary, purse string sutures incorporating the distal portions of the uterosacral ligaments can be used to close the defect (see Fig. 54–34). Fascial reconstruction is accomplished by reapproximating the vagina with its underlying fascia. However, if a vaginal vault suspension is needed, then the defect is closed as part of the suspension procedure. If a sacrospinous or ileococcygeus suspension is to be performed, the enterocele is closed with a purse string suture, and the pararectal space is entered lateral to the enterocele sac to allow access to these sutures (see Chapter 55, Vaginal Repair of Vaginal Vault Prolapse).

Rectocele Repair

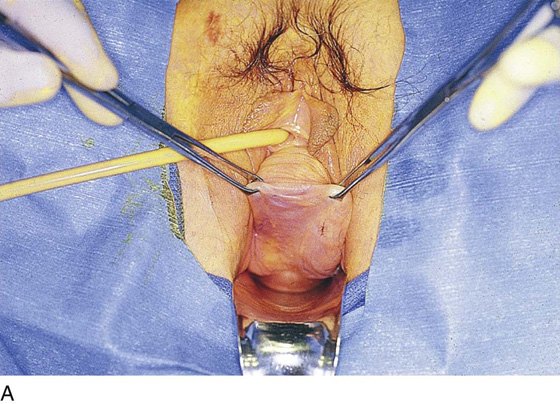

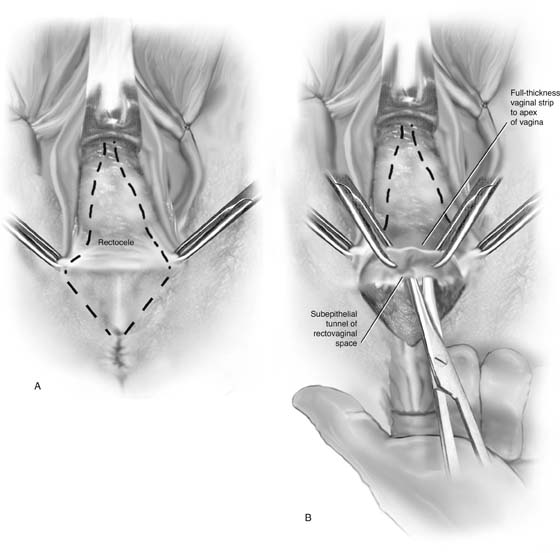

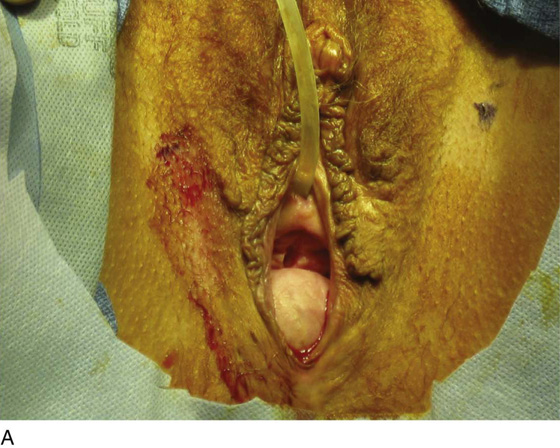

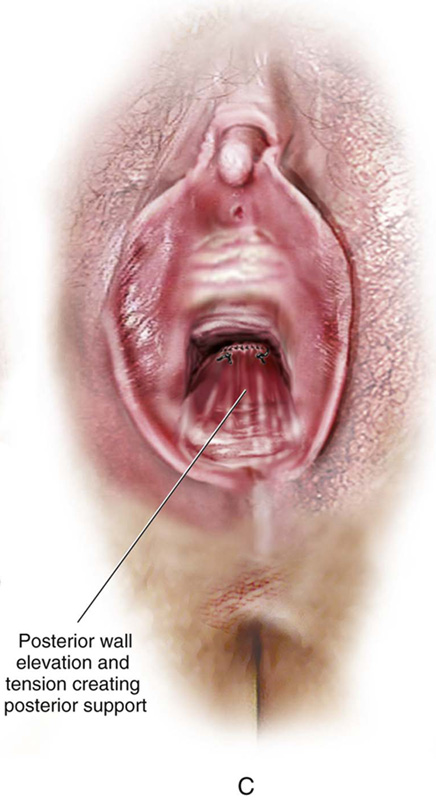

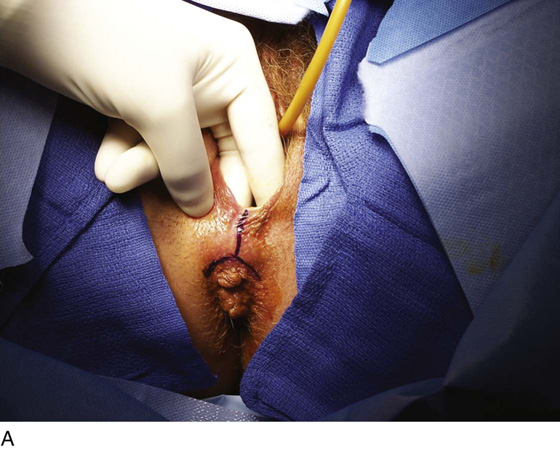

Repair of a relaxed perineum and repair of a rectocele are two distinct operative procedures, although they are usually performed together. Before beginning the repair, the surgeon should estimate the severity of the rectocele and the perineal defect, as well as the desired postoperative caliber of the vagina and introitus (Fig. 54–40). The ultimate size of the vaginal orifice is determined by placing an Allis clamp on the inner aspect of the labia minora bilaterally and approximating them in the midline. The final vaginal opening should admit two or three fingers, but the surgeon must take into account that the levator ani and perineal muscles are completely relaxed from the anesthesia, and the vagina may further constrict postoperatively.

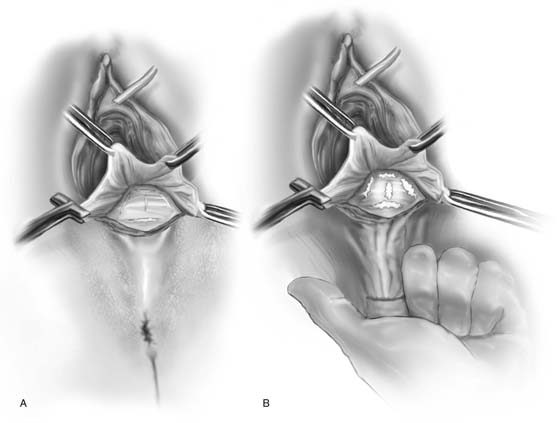

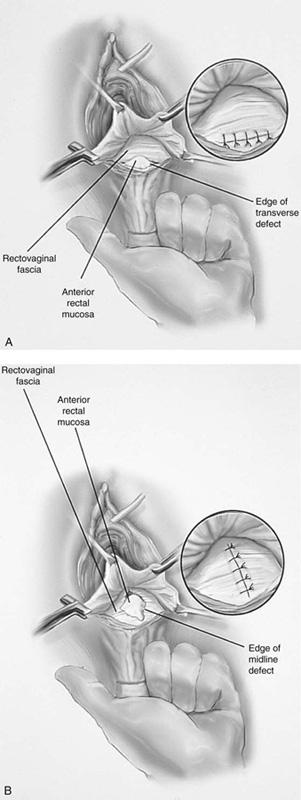

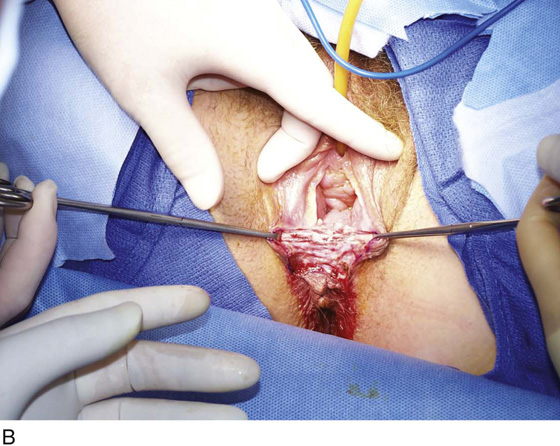

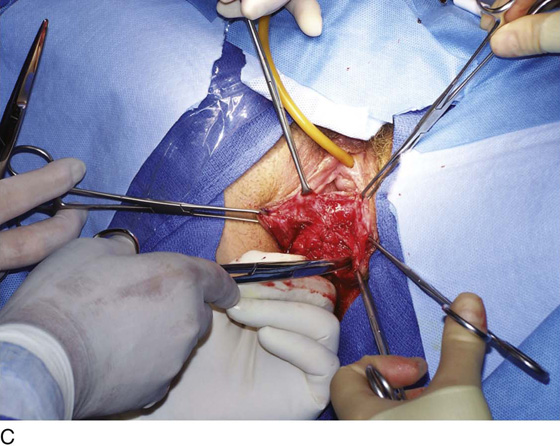

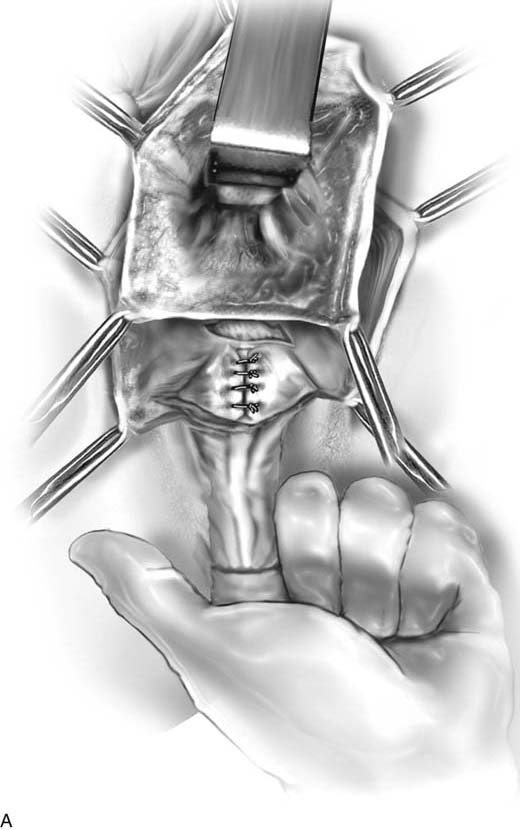

To begin the repair, a triangular incision is made in the perineal skin (see Fig. 54–40). Sharp dissection is used to detach the posterior vaginal wall off the underlying anterior rectal wall (see Fig. 54–40). The dissection is extended to the apex of the vagina and bilaterally to the rectovaginal space. Many times a strip of vaginal epithelium in the midline is removed, leaving enough vagina to repair the rectocele and leave appropriate vaginal caliber. Historically, posterior colporrhaphy has involved a levatorplasty in which the dissection is extended laterally as far as possible to mobilize perirectal fascia and expose the medial margins of the puborectalis muscle (Fig. 54–41). The terminal ends of the bulbocavernosus and transverse perineal muscles are also freed from the epithelium adherent to the lower vagina. The author prefers to avoid levatorplasty during posterior colporrhaphy except in cases of massive prolapsed, when a levatorplasty is the only mechanism available to decrease the size of the vaginal introitus. Routine use of levatorplasty at the time of posterior colporrhaphy may create vaginal distortion, constriction, postoperative pain, and dyspareunia. The author prefers a site-specific defect approach to rectocele repair. This is best performed by identifying rectovaginal fascial defects with a finger in the rectum elevated toward the vagina (Figs. 54–42 and 54–43). Various possible defects are transverse, longitudinal, or oblique (see Figs. 54–42 and 54–43). The edges of the defects are identified and approximated with interrupted 2-0 absorbable sutures (see Fig. 54–43). Whereas rectocele repair is accomplished by identification of fascial defects and reapproximation of connective tissue, evaluation of the levator hiatus is an entirely different issue. As was previously mentioned in women with an enlarged levator hiatus, it may be appropriate to place another set of interrupted sutures horizontally to narrow the levator hiatus (see Fig. 54–41). This portion of the operation is not necessary in all patients and is independent of the rectocele.

Perineorrhaphy is the third part of the posterior segment reconstruction. The perineal body consists of the anal sphincter, superficial and deep transverse perineal muscles, the bulbocavernosus muscles, and the junction of the rectovaginal fascia to the anal sphincter. Perineorrhaphy involves identification and reconstruction of these components and is discussed separately under the section on perineal surgery.

Figure 54–44 demonstrates repair of a low rectocele with various defects; note the mobilization and approximation of the fascial edges.

FIGURE 54–31 Cross-section of the pelvic floor showing various anatomic locations of enteroceles. A. Anterior enterocele defect in the pubocervical fascia near its attachment to the vaginal apex. The peritoneal sac with its contents protrudes into the vaginal opening. B. Apical enterocele defect at the vaginal apex; the peritoneal sac protrudes between the pubocervical fascia anterior and the rectovaginal fascia posterior. C. Posterior enterocele defect posterior to the vaginal cuff. The peritoneal sac protrudes through the defect into the rectovaginal fascia.

FIGURE 54–32 High posterior enterocele. Allis clamps apply traction to the most dependent portion of the enterocele. In this patient, the vaginal apex, anterior vaginal wall, and distal posterior vaginal wall are all well supported. This thus represents an isolated high posterior enterocele.

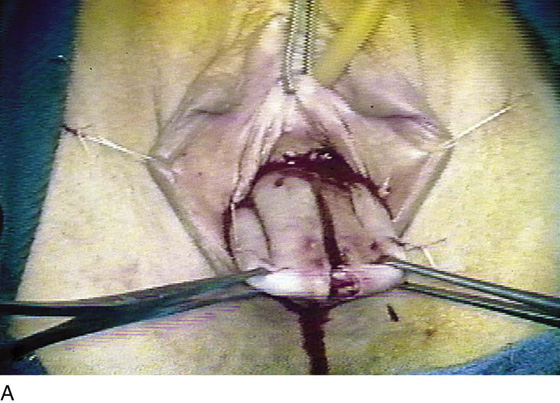

FIGURE 54–33 Large enterocele associated with vaginal vault prolapse. A. The midline posterior vaginal wall incision extends from the proximal edge of the pubocervical fascia to the proximal edge of the rectovaginal fascia. B. Sharp dissection is used to separate the enterocele sac from the anterior rectal wall. C. The enterocele sac has been excised to its neck.

FIGURE 54–34 Dissection and vaginal repair of enterocele. A. The enterocele sac has been completely mobilized off the vaginal epithelium. B. A finger in the rectum facilitates sharp dissection of the enterocele sac off the anterior wall of the rectum. C. The enterocele sac is sharply entered. D. The peritoneum has been excised, and the cul-de-sac is exposed. E. A series of purse string sutures incorporating the distal ends of the uterosacral ligaments are placed to close the defect at its neck. F. The vaginal apex is attached to the plicated uterosacral ligaments.

FIGURE 54–35 A. Complete uterine prolapse with a large enterocele. B. The uterus has been removed; note the complete prolapse of the vaginal vault with a large enterocele. C. The enterocele sac is sharply dissected off the posterior vaginal wall up to the level of the neck of the hernia.

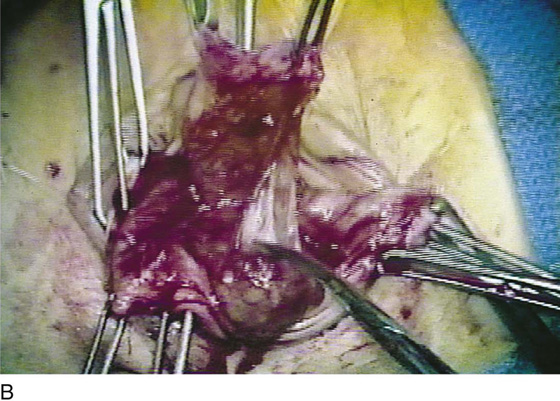

FIGURE 54–36 A. Note that the posterior enterocele is identified with a finger in the rectum, and the enterocele sac has been mobilized off the anterior wall of the rectum. B. The enterocele sac has been sharply entered, and the neck of the enterocele is identified.

FIGURE 54–37 A. Note complete vaginal vault eversion secondary to a large enterocele and cystocele. B. The Allis clamps are grasped at the apex of the vagina. C. The anterior vaginal wall has been dissected off the underlying cystocele. At the base of the cystocele or the apex of the vagina, the enterocele sac is identified and sharply entered. The large intraperitoneal portion of the cystocele is identified.

FIGURE 54–38 Large vaginal prolapse. A. The apex of the vagina is grasped with two Allis clamps, and posterior to this a large enterocele is identified. B. Sharp dissection with a finger in the rectum facilitates dissection of the enterocele sac away from the anterior wall of the rectum. C. The enterocele sac has been sharply identified, and the neck of the enterocele is noted. D. Note extensive omental adhesions in the cul-de-sac.

FIGURE 54–39 Anterior enterocele. A. The prolapse is identified; note that the prolapse is anterior to the apex of the vagina, denoting that this is a high cystocele or an anterior enterocele. B. The vaginal wall has been opened, and dissection of the prolapse off the apex of the vagina is being performed. C. The enterocele sac is identified and sharply entered.

FIGURE 54–40 A. The dashed line indicates the area of perineal skin and posterior vaginal wall to be excised. B. Sharp dissection of the posterior vaginal wall from the anterior rectal wall; dissection is aided with a finger in the rectum.

FIGURE 54–41 Technique of levatorplasty. A. The posterior vaginal wall has been opened up, and the levator muscles are identified laterally. Absorbable sutures are taken through the levator muscles on each side. Note that the fascia over the anterior wall of the rectum is totally ignored, and the support that occurs is based on the levator muscles’ being tied across the midline. B. The levators have been tied, and a posterior vaginal ridge is created that is intended to support the posterior vaginal wall.

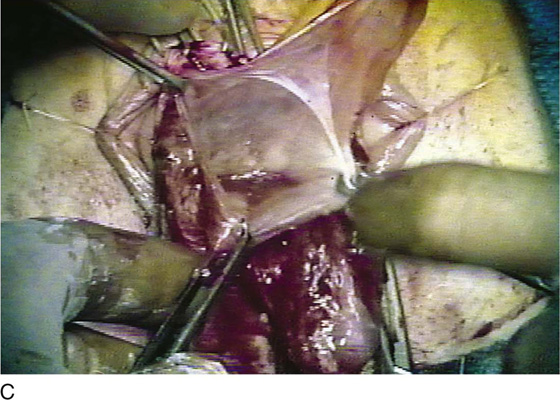

FIGURE 54–42 A. Various potential defects that may be encountered at the time of rectocele repair. B. Placing a finger in the rectum and elevating the anterior rectal wall help to further delineate fascial tears.

FIGURE 54–43 A. A low transverse defect between the perineum and the distal edge of the rectovaginal fistula. Inset. Defect-specific closure with interrupted sutures. B. A midline longitudinal defect. Inset. Defect-specific closure with interrupted sutures.

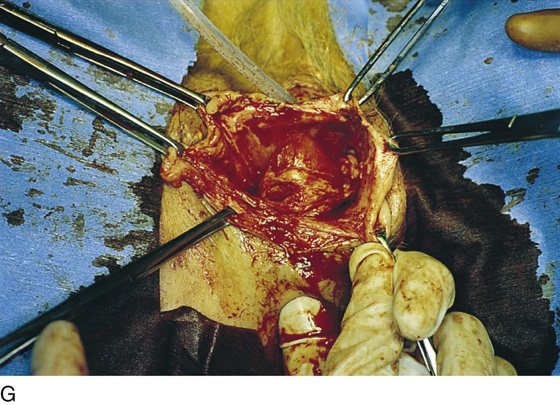

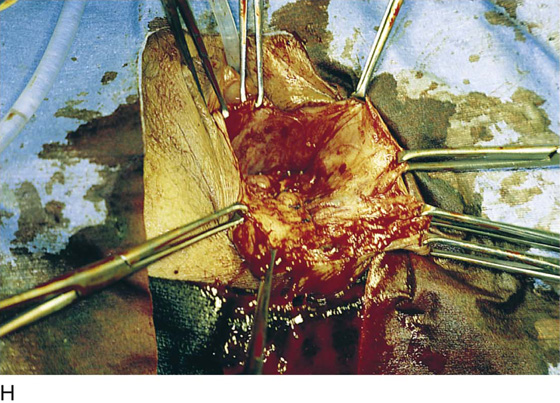

FIGURE 54–44 A. A distal rectocele with attenuated perineum. B. The initial wedge of perineal skin has been removed. This incision should be tailored to the desired size of the introitus. This can be estimated by placing two Allis clamps on the edges of the incision and approximating them across the midline. C. Sharp dissection has been utilized to completely mobilize the posterior vaginal wall from the anterior rectal wall. Note that a narrow piece of vagina has been dissected in the midline. The width of this segment of vagina is determined by estimating the amount of vagina that will need to be trimmed. D. Identification of fascia to be utilized for plication over the anterior rectal wall. E. Mobilization of the fascia off the posterior vaginal wall. F. The fascia has been completely mobilized off the right vaginal wall. Note that the midline wedge of vaginal skin has no underlying fascia, confirming a midline defect. G. A high transverse defect is demonstrated. Note that the fascia is present over the distal anterior rectal wall. H. Completed fascial defect repair. Note that durable fascia has been plicated over the entire anterior wall.

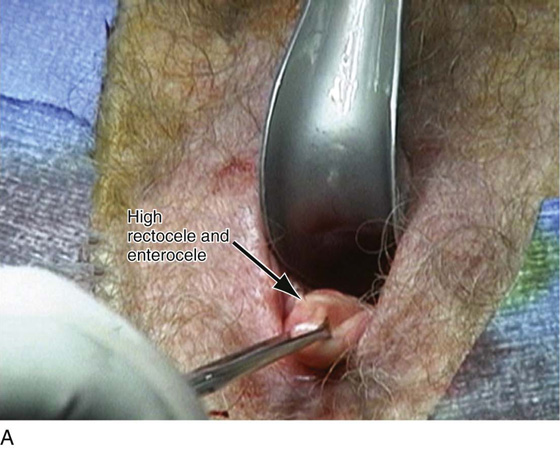

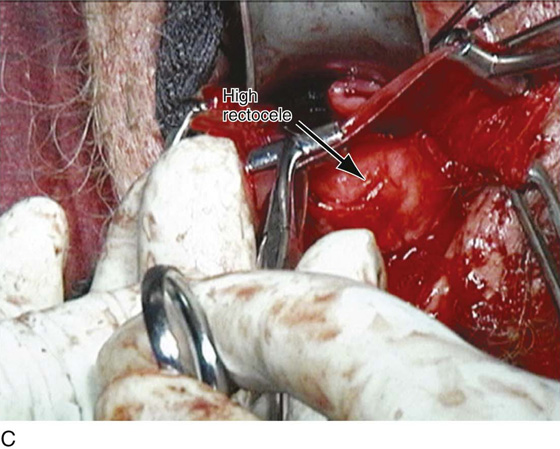

High rectoceles are very commonly associated with an enterocele. On examination the vagina over an enterocele will usually have a thin, smooth appearance in comparison with the thicker-appearing mucosa over the rectocele (Fig. 54–45). In cases of high posterior vaginal wall defects, it is important to dissect up to the vaginal apex in search of an enterocele sac. Figure 54–46 demonstrates the technique of rectocele repair in conjunction with vaginal suspension and perineal reconstruction. Figure 54–47 shows how suspending the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall overlying an enterocele can contribute to the overall support of the entire posterior vaginal wall (see section on high uterosacral ligament suspension in Chapter 55). At times, posterior colporrhaphy with perineoplasty is done in conjunction with external anal sphincter repair (Fig. 54–48).

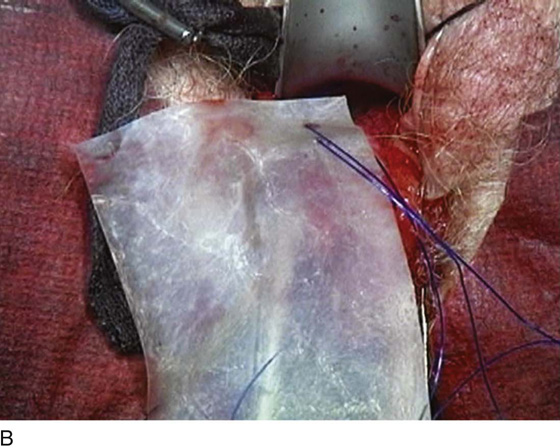

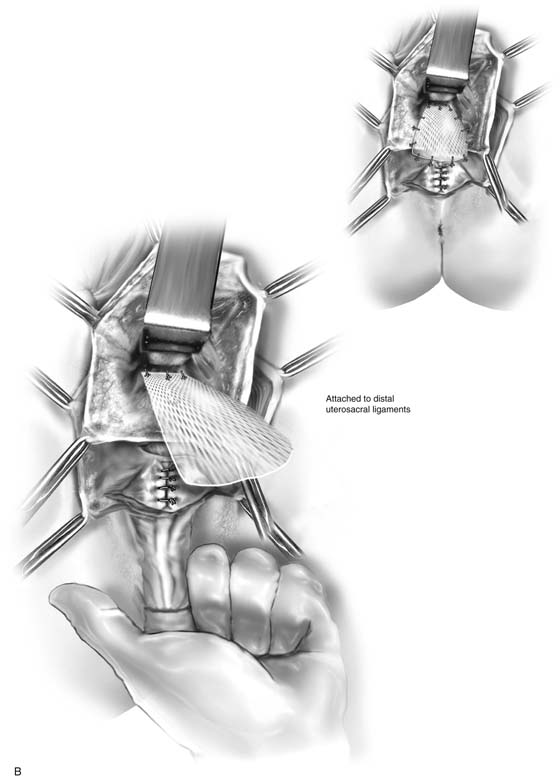

Some surgeons have advocated augmenting posterior colporrhaphy with an intervening mesh. At present, the indications and preferred material for such a repair remain controversial. Figures 54–49 and 54–50 demonstrate the technique of utilization of a mesh to augment posterior vaginal wall repair.

FIGURE 54–45 High posterior vaginal wall defect secondary to a posterior enterocele in conjunction with a rectocele. On examination, the vagina over the enterocele wall appears smoother and thinner.

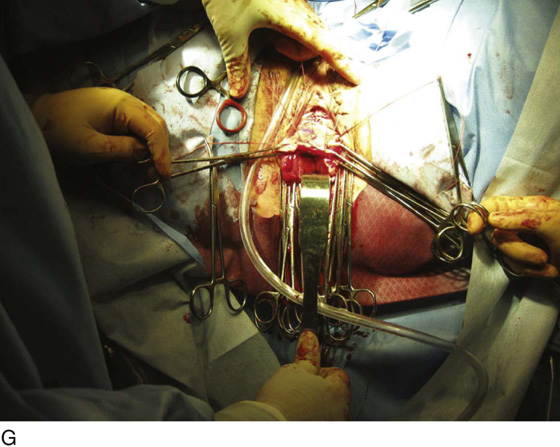

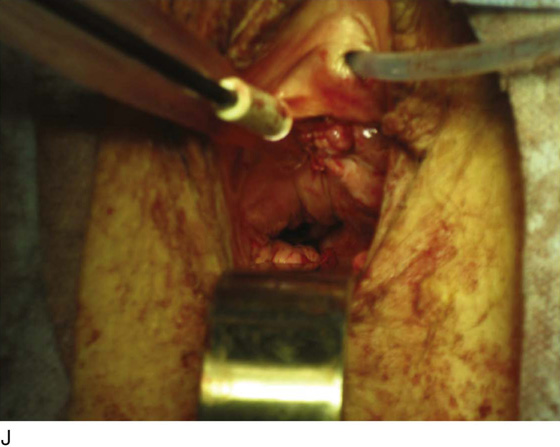

FIGURE 54–46 Patient with recurrent prolapse secondary to a rectocele and enterocele. A. Large posterior vaginal wall defect with a somewhat foreshortened vagina. B. Note the previous inappropriate buildup of perineal skin. C. The perineal skin has been cut longitudinally down to the level of the posterior fourchette. D. With a finger in the rectum, sharp dissection is used to mobilize the posterior vaginal wall off the anterior wall of the rectum. E. The dissection is extended cephalad; note the excessive amount of pararectal, preperitoneal fat encountered. F. The enterocele sac is sharply entered. G. High intraperitoneal uterosacral sutures have been placed (see Chapter 55) and passed through the vaginal apex to suspend the vaginal vault. H. The vaginal vault stitches have been tied, the rectocele plicated, and the perineum reconstructed. I. Note the perpendicular relationship between the perineum and the posterior vaginal wall. J. Note the good vaginal depth with no deviation of the vaginal axis.

FIGURE 54–47 A. Posterior vaginal wall defect secondary to an enterocele and rectocele. B. After entry into the enterocele sac, intraperitoneal suspension sutures are brought out through the full thickness of the vaginal wall at the level of the apex. C. Tying of these sutures after closure of the vaginal incision at the apex not only will result in an increase in vaginal length but also will contribute to the overall support of the entire posterior vaginal wall.

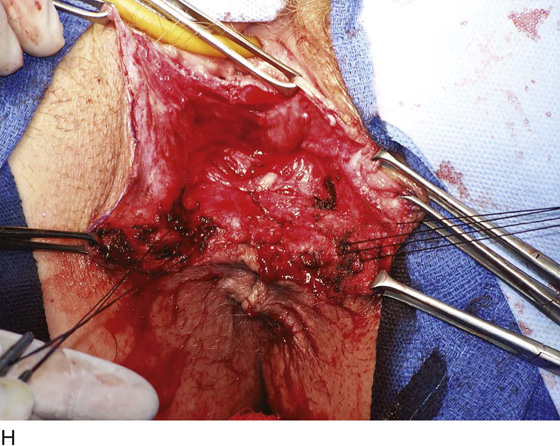

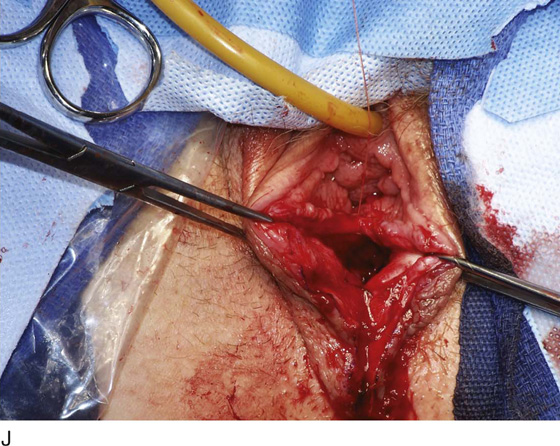

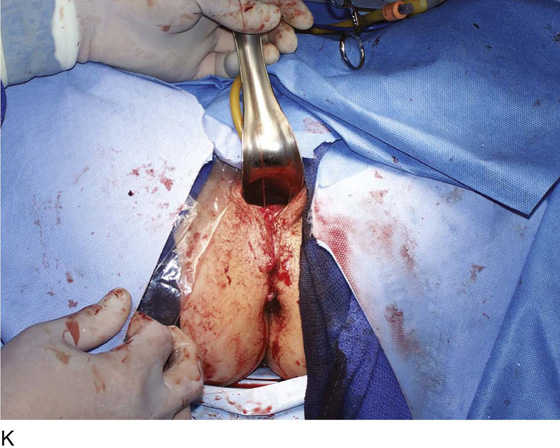

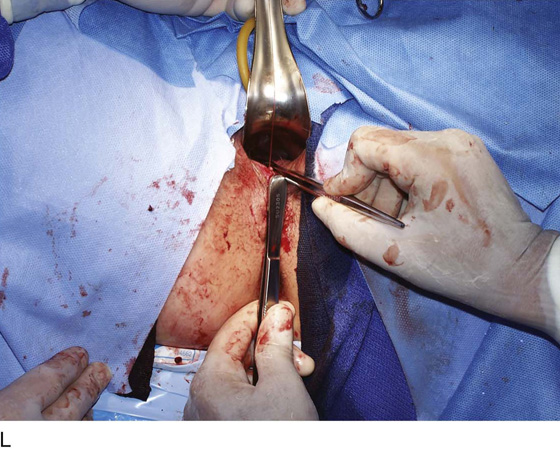

FIGURE 54–48 Patient with a symptomatic rectocele and fecal incontinence secondary to a sphincter defect. A. Perineal incision to be made is marked. B. After hydrodissection, a perineal incision is made. C. Sharp dissection, with a finger in the rectum, is utilized to mobilize the perineal skin and the posterior vaginal wall. D. Sharp dissection is extended cephalad toward the vaginal apex. E. The rectocele is isolated. F. A defect-specific rectocele repair has been performed and monopolar cautery is being used to identify viable external anal sphincter. G. Note the widened caliber of the anal opening before sphincter repair. H. Sutures have been passed through the retracted ends of the external anal sphincter. I. After the sphincteroplasty has been performed, note the significant decrease in caliber of the opening of the anus. J. The upper portion of the vaginal incision is closed with a fine continuous absorbable suture. K. The repair is completed. Note the significant building up of the perineal body. L. The appropriate perpendicular relationship between the perineum and the posterior vaginal wall is demonstrated.

FIGURE 54–49 Posterior vaginal wall defect. A. Note that the rectocele has been plicated in the middle and distal vagina. A high rectocele remains, and the enterocele sac has been opened. B. In such a situation, mesh can be attached proximally to the distal portions of the uterosacral ligaments intraperitoneally and distally to the upper margin of the plicated rectovaginal fascia, thus supporting the high rectocele.

FIGURE 54–50 Patient with a somewhat tightened vaginal introitus who has a recurrent prolapse of the upper portion of the posterior vaginal wall, secondary to a high rectocele and an enterocele. A. An Allis clamp is used to identify the prolapsed portion of the posterior vaginal wall. B. The vagina has been opened in the midline. A piece of biologic mesh is being attached proximally to the distal portions of the uterosacral ligaments intraperitoneally. C. The mesh has been attached proximally to the uterosacral ligaments, and the high rectocele is noted. A finger in the rectum identifies the defect, and the mesh will be placed over this defect and sutured to the proximal margins of the rectovaginal fascia. D. The mesh has been attached proximally and distally, as well as laterally, to the levator muscles. Note that the mesh nicely supports the previously noted high rectocele.