Vaginal Bleeding

Perspective

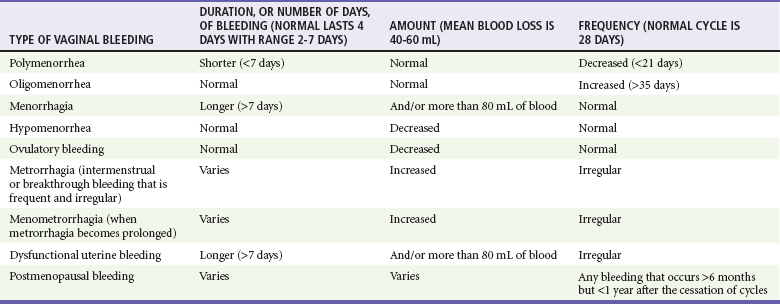

Vaginal bleeding includes uterine and extrauterine causes. Uterine causes include the constellation of normal uterine bleeding, abnormal uterine bleeding, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding, which is abnormal uterine bleeding in the absence of organic disease. Normal menstrual bleeding occurs cyclically in women who have achieved menarche (the onset of menses), mean age 12.5 years, until menopause (the cessation of menses), mean age 51 years, in North America. The normal cycle, defined as the first day of bleeding of one cycle to the first day of bleeding of the next cycle, lasts 28 days, plus or minus 7 days, and the average volume of blood loss is 60 mL. Vaginal bleeding is defined temporally as midcycle (ovulatory, or at the release of an ova), premenstrual, menstrual, and postmenstrual. Abnormal vaginal bleeding is classified on the basis of the duration, amount, and frequency of bleeding (Table 34-1). Abnormal vaginal bleeding occurs in women of all ages, and it can result from a number of causes, including anatomic abnormalities, complications of pregnancy, hematologic disorders, infections, malignancies, medications, obesity, systemic diseases, and endocrinologic imbalances. Premenarchal or postmenopausal vaginal bleeding is rarely life-threatening, but bleeding as a complication of pregnancy has a significantly increased risk of morbidity and mortality for the mother and fetus1,2 (see Chapter 178).

Epidemiology

Approximately 5% of women aged 30 to 45 years will see a physician for vaginal bleeding annually. Menorrhagia (regular heavy bleeding) secondary to anovulation is seen in 10 to 15% of all gynecologic patients. Excessive menstrual bleeding accounts for two thirds of all hysterectomies and most endoscopic endometrial destructive surgery. The consequences of menorrhagia include anemia and iron deficiency, reduced quality of life, and increased health care costs.3 Because black women are more likely to have leiomyomas (fibroids), they experience disproportionately more morbidity from menorrhagia. Invasive neoplasms of the female pelvic organs account for almost 15% of all cancers in women. The most common of these malignancies is uterine cancer, specifically, endometrial cancer. Approximately 10% of postmenopausal bleeding is eventually diagnosed as endometrial cancer. Endometrial cancer is associated with obesity, diabetes mellitus, anovulatory cycles, nulliparity, and age older than 35 years. Both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix are causally related to infection with the human papillomavirus (HPV), especially types 16 and 18. Smoking and possible dietary factors, such as decreased circulating vitamin A, appear to be cofactors. Preinvasive cancer (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN III]) is a common diagnosis in women 25 to 40 years of age.

Pregnant Patients

Vaginal bleeding after the 20th week of gestation occurs in approximately 4% of pregnancies; approximately 30% of cases are caused by placental abruption (abruptio placentae), and 20% are caused by placenta previa. The most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage in the first 24 hours is uterine atony, but after 24 hours the presence of retained products of conception is the more frequent cause.4

Pathophysiology

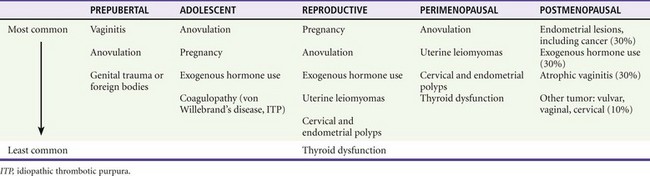

Causes of vaginal bleeding in nonpregnant women are classified as ovulatory, anovulatory, and nonuterine. Ovulation bleeding, a single episode of spotting between regular menses, is quite common. Approximately 90% of dysfunctional uterine bleeding cases result from anovulation, and the other 10% of cases occur with ovulatory cycles. When ovulation does not occur, there is overgrowth of the endometrium because of estrogen stimulation without progesterone to stabilize growth. This results in a persistent proliferative endometrium. Patients at the extremes of menarche are more likely to have endocrinologic causes of disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian system resulting in anovulation. In addition, disruption of this axis is seen with excessive stress, weight loss, and exercise. Bleeding outside the uterus also is considered, including lesions of the vulva, vagina, or cervix, as well as uterine tumors, adnexal masses, and urethral, rectal, and anal disorders.5 Prepubertal female children may have foreign bodies, genital trauma, or severe vulvovaginitis causing mucosal breakdown and hemorrhage. Exogenous hormone use, most commonly in progesterone-only oral contraceptives and in intrauterine devices, is very common in reproductive-age women. Leiomyomas (fibroids) cause hemorrhage by disrupting the endometrial vascular supply and the ability of the uterus to contract to stop bleeding. Cervical and endometrial polyps have vascular pedicles and are prone to bleed.

Pregnant Patients

The differential diagnosis of vaginal bleeding in early pregnancy (before the 20th week of gestation) includes ectopic pregnancy; spontaneous, threatened, complete, incomplete, inevitable, missed, or infected (septic) abortions; implantation bleeding; cervicitis; cervical conditions such as polyp or ectropion; bleeding from the urinary or gastrointestinal tract; trauma and cervical carcinoma; and gestational trophoblastic disease (hydatidiform mole, molar pregnancy). Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy include tubal abnormalities caused by past infection, surgical scarring, or assisted reproductive techniques. Disruption of the blood supply to the ectopic gestational sac can cause hemorrhage into the fallopian tube, or the size of the developing fetus can lead to rupture through the tubal wall.6,7 Life-threatening vaginal bleeding after the first trimester is often a result of placental abruption. This can occur spontaneously or secondary to abdominal trauma with transmission of forces to the uterus. An increased incidence is seen in association with cocaine use, hypertension, preeclampsia, HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome, smoking, increased maternal age, and abnormal implantation of the placenta (e.g., placenta previa, accreta, increta, or percreta). Placenta previa occurs when the implanted placenta overlays the cervical os. Bleeding is caused by partial separation of the placenta from the uterine wall. Postpartum uterine atony occurs when myometrial dysfunction prevents the uterine corpus from contracting, allowing continued bleeding at the placental site. Atony is more likely to occur with conditions that overdistend the uterus, such as polyhydramnios, multiparity, prolonged labor, induced labor, high Pitocin use during labor, precipitous labor, magnesium therapy, or intrauterine infection (chorioamnionitis).8 Complications of pregnancy, including vaginal bleeding, are discussed in Chapter 178.

Diagnostic Approach

The differential diagnosis can be categorized by age of presentation and frequency of cause (Table 34-2). Primary coagulation disorders account for almost 20% of acute menorrhagia in adolescents. Von Willebrand’s disease is the most common; however, myeloproliferative disorders and immune thrombocytopenia are also possibilities.9 Ectopic pregnancy should be considered in all women of childbearing age with abdominal or pelvic complaints or with unexplained signs or symptoms of hypovolemia. Additional uterine disorders include endometrial cancer, endometriosis, leiomyomata, adenomas, and sarcomas.

Pivotal Findings (Symptoms, Signs, and Laboratory)

Signs

Uterine size, measured from the symphysis pubis to the fundus, is the quickest means of estimating gestational age. This distance in centimeters equals the gestational age in weeks (e.g., 24 cm = 24 weeks), which allows some early estimation of fetal viability if delivery is necessary. As a general guide, the fetus is potentially viable when the dome of the uterus extends beyond the umbilicus. Fetal heart tones can be detected by auscultation at 20 weeks of gestation or by Doppler probe at 10 to 14 weeks. If either the uterus is less than 24 cm in size or fetal heart tones are absent, the pregnancy is probably too early to be viable, and treatment is directed solely at the mother. The limit of viability is the gestational age at which a prematurely born fetus/infant has a 50% chance of long-term survival outside its mother’s womb. The cutoff point of 24 weeks has not changed in 12 years, and in general, neonatologists would not resuscitate before 23 weeks. The grey area is 24 to 25 weeks’ gestation, accounting for approximately 2 per 1000 births.9

Ancillary Testing

In hemodynamically compromised patients, hematocrit, platelet count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, ABO and Rh typing, and crossmatching of blood should be done. Bedside ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice for simultaneous assessment of the mother and the fetus. In the pregnant trauma patient, it is useful in the detection of major abdominal injury (sensitivity 80%, specificity 100%) and for establishing fetal well-being or demise, gestational age, and placental location.10 Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are rarely indicated in the evaluation of vaginal bleeding, except in the case of pregnant trauma patients to diagnose potentially life-threatening injuries in those patients not proceeding directly to surgical intervention.

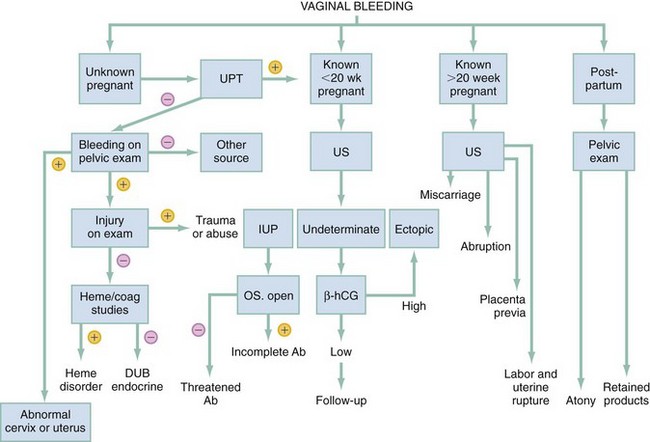

Qualitative pregnancy tests in clinical use are typically reported as positive when the β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) concentration is 20 mIU/mL or higher in urine and 10 mIU/mL or higher in serum. At this level of detection, the false-negative rate for detection of pregnancy is less than 1% for urine and 0.5% or less for serum. In clinical use the performance of urine qualitative testing has been found to be 95 to 100% sensitive and specific compared with serum testing. When a urine test result is negative and ectopic pregnancy is still being considered, a quantitative serum test should be performed. The sensitivity of quantitative serum testing for the diagnosis of pregnancy is virtually 100% when an assay capable of detecting 5 mIU/mL or more of β-hCG is used.11 The discriminatory level of serum β-hCG for ectopic pregnancy is 1500 to 2000 mIU/mL.12 Additional testing, such as progesterone level, may help to distinguish normal versus abnormal pregnancy. A progesterone level of 5 ng/mL or less indicates a nonviable pregnancy, such as ectopic pregnancy or miscarriage, and excludes a normal pregnancy with 100% sensitivity.12 Management of ectopic pregnancy is discussed in Chapter 178.

Additional testing for the stable, nonpregnant emergency department patient may be considered on an outpatient basis, depending on availability of follow-up with appropriate, that is, gynecologic, hematologic, or endocrinologic, specialists. This includes thyroid function testing, prolactin levels, or other disorders of the hypothalamic-pituitary tract, including progesterone. For coagulation pathway investigation, a blood smear can determine if there are shistocytes, which would indicate thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) and warrants further inpatient workup and treatment.14

Diagnostic Algorithm

The most critical diagnoses to make are ectopic and heterotopic pregnancy, miscarriage, placenta previa or accreta or placental abruption, uterine rupture or trauma, and arteriovenous malformation. The most important factor is to determine the pregnancy status. This may be done by history, for example for the immediate postpartum patient, but when unknown or in doubt, the urine pregnancy test can be obtained. Bedside transabdominal ultrasound helps to determine whether or not there is an IUP and whether or not there is intra-abdominal fluid. Transvaginal ultrasound is optimal, especially with suspected ectopic pregnancy, but may not be immediately available. If there is an IUP of viable age (24 weeks) with no intra-abdominal free fluid, avoid manipulation of the cervix but consider placenta previa or accreta or placental abruption, miscarriage, or arteriovenous malformation. In following the diagnostic algorithm (Fig. 34-1) for early pregnancy, the most frequent diagnosis will be threatened abortion.

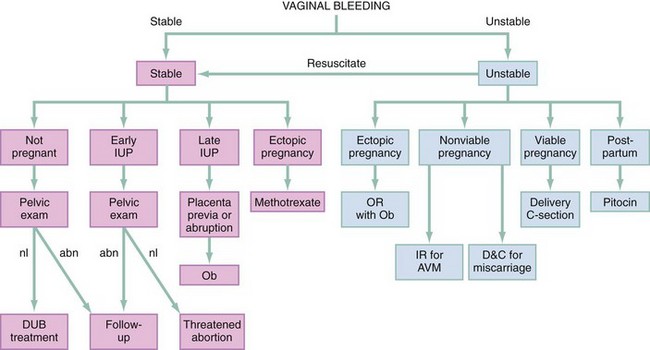

Empirical Management

All patients should be resuscitated with oxygen, intravenous crystalloid, and blood transfusion as needed. Use Rh-negative blood in women of child-bearing age with unknown Rh status. A patient in shock with a surgical abdomen or evidence of intra-abdominal free fluid should be resuscitated and promptly evaluated with immediate consideration of operative intervention in consultation with obstetrics and gynecology or general surgery. For a viable pregnancy to be saved, possible emergent cesarean section in the operating room may be required. For IUP of nonviable age, arteriovenous malformation (AVM), ectopic or heterotopic pregnancy, and miscarriage are considered; possible management includes dilation and evacuation or curettage. Management of the pregnant patient is discussed in detail in Chapter 178. When intra-abdominal fluid is present, regardless of pregnancy status, surgical and possible interventional radiology consultation should be undertaken. Consideration is given to ruptured uterus, ruptured ectopic or heterotopic pregnancy, or ruptured spleen or liver, and the patient should be brought the operating room for surgical and radiologic intervention. If vaginal bleeding is persistent and life-threatening, hysterectomy may be performed (Fig. 34-2).

In nonpregnant patients, heavy vaginal bleeding may be under ovulatory control or related to anovulatory dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are the mainstay of treatment for both conditions, although the exact mechanism of action is not clearly understood.15 In nonpregnant hemodynamically unstable patients, intravenous (IV) or intramuscular (IM) conjugated estrogen (Premarin) 25 mg may be administered, with repeat doses in 4 to 6 hours. If bleeding continues after IV or IM, a pediatric Foley catheter inserted into the cervical os and inflated can tamponade the bleeding. The balloon is distended with saline until the bleeding stops. A larger balloon may be needed, and this can be left in place for 12 to 24 hours.16

Disposition

Any patient with continued symptomatic bleeding, especially with persistent hypotension and low hematocrit, should be admitted to the hospital for management and possible transfusion. In a patient with stable vaginal bleeding, medical management is often sufficient. In a preadolescent patient, abuse should be ruled out before the patient is discharged to her current environment. All patients with abnormal uterine bleeding should receive close follow-up from a primary care physician or gynecologist. In a nonpregnant stable patient, malignancy should be considered, and additional inpatient or timely outpatient gynecologic follow-up is indicated. Laboratory studies, such as thyroid function and prolactin levels, may be helpful to the consultant or in the initial outpatient workup of dysfunctional uterine bleeding, but they are not required in the emergency department.17

References

1. Clinical policy for the initial approach to patients presenting with a chief complaint of vaginal bleeding. American College of Emergency Physicians. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;29:435.

2. ACEP Clinical Policies Committee and Clinical Policies Subcommittee on Early Pregnancy. American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: Critical issues in the initial evaluation and management of patients presenting to the emergency department in early pregnancy. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:123.

3. Frick, KD, et al. Financial and quality-of-life burden of dysfunctional uterine bleeding among women agreeing to obtain surgical treatment. Womens Health Issues. 2009;19:70–78.

4. Oyelese, Y, Scorza, WE, Mastrolia, R, Smulian, JC. Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:421.

5. Daniels, R, McCuskey, C. Abnormal vaginal bleeding in the non-pregnant patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:45.

6. Coppola, P, Coppola, M. Vaginal bleeding in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:41.

7. Della-Giustina, D, Denny, M. Ectopic pregnancy. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:565.

8. Ananth, CV, Oyelese, Y, Yeo, L, Pradhan, A, Vintzileos, AM. Placental abruption in the United States, 1979 through 2001: Temporal trends and potential determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:191.

9. Vavasseur, C, Foran, A, Murphy, JF. Consensus statements on the borderlands of neonatal viability: From uncertainty to grey areas. Ir Med J. 2007;100:561–564.

10. Brown, MA, Sirlin, CB, Farahmand, N, Hoyt, DB, Casola, G. Screening sonography in pregnant patients with blunt abdominal trauma. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:175.

11. Pitkin, J. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. BMJ. 2007;334:1110–1111.

12. Kaplan, BC, et al. Ectopic pregnancy: Prospective study with improved diagnostic accuracy. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;28:10.

13. Reference deleted in proofs.

14. James, AH, et al. Von Willebrand disease and other bleeding disorders in women: Consensus on diagnosis and management from an international expert panel. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:12.e1–12.e8.

15. Lethaby, A, Augood, C, Duckitt, K, Farquhar, C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2007.

16. Estaphan, A, Dyne, PL. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding: treatment and management. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/795587-treatment, 2012.

17. Dickersin, K, et al. Hysterectomy compared with endometrial ablation for dysfunctional uterine bleeding: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1279–1289.