Chapter 31 Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty – the Fairbanks technique

1 INTRODUCTION

Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) is generally both safe and effective as a surgical treatment for non-obese patients who suffer with mild to moderate sleep apnea and severe snoring. This refinement in surgical technique1 employs strategies for avoidance of complications and improvement of efficacy. Palatal dysfunction is avoided by minimization of soft palate shortening in the midline (uvula) area. Nasopharyngeal stenosis is avoided by minimization of posterior pillar resection and avoidance of pharyngeal undermining. Effectiveness of surgery is improved when emphasis is placed on opening the nasopharynx widely in the lateral port areas. Also, tissue removal deep in the inferior tonsillar poles (and hypopharynx) with mucosal advancement and suturing is emphasized.

1.2 OBJECTIVES

The technique described here resembles the original descriptions of Ikematsu2 and Fujita.3 However, it is modified to achieve the following desirable objectives.

2 SURGICAL PROCEDURE AND TECHNIQUE

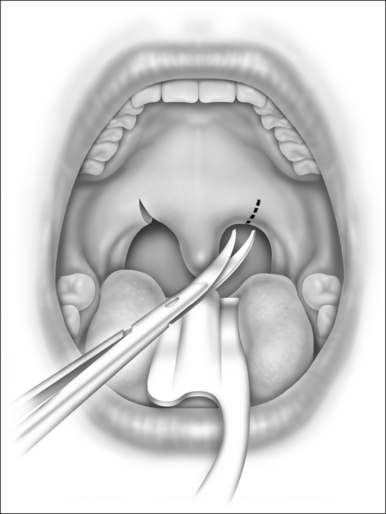

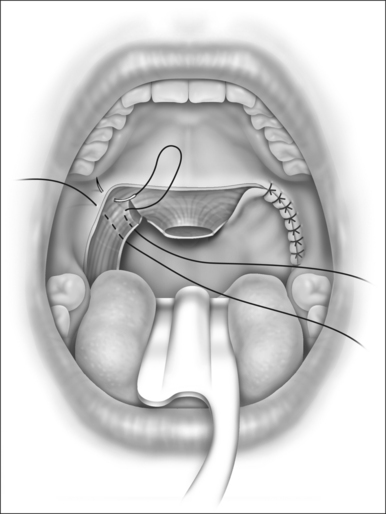

The mucosa on either side of the uvula is clamped with hemostats and then incised in an oblique direction as in Figure 31.1. This severs the drooping mucosal web between the uvula and the posterior pillar, increases the mobility of the pillar, prevents soft palatal scar contraction (with ‘tethering’), and incises some of the lowermost fibers of the nasopharyngeal sphincter. Typically, the low-hanging soft palate of an apnea patient contains few muscular fibers of the nasopharyngeal sphincter.

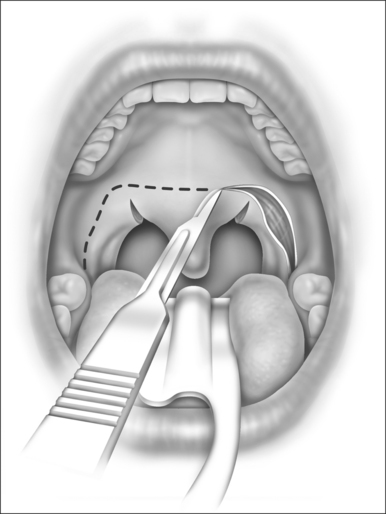

The palatopharyngeal incision is designed as three sides of a rectangle, as in Figure 31.2. It begins at the base of the tongue lateral to the inferior tonsillar pole and extends cephalad in the sulcus or angle formed between the internal surface of the mandible and the anterior tonsillar pillar. At about 1 cm above the level of the trailing edge of the soft palate, the incision makes a 90 angle, transverses the soft palate horizontally, then angles 90 downward again symmetrical to the opposite side. The ideal level for the horizontal palatal incision is at the location of the palatal ‘dimple’ as described by Dickson.4

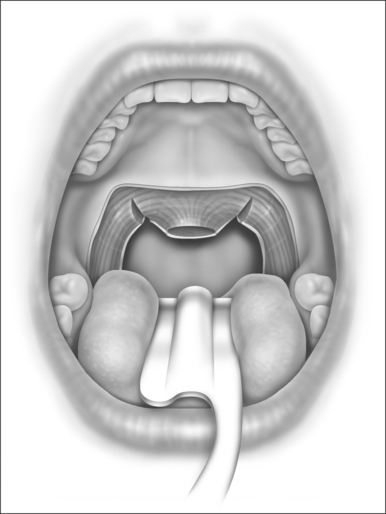

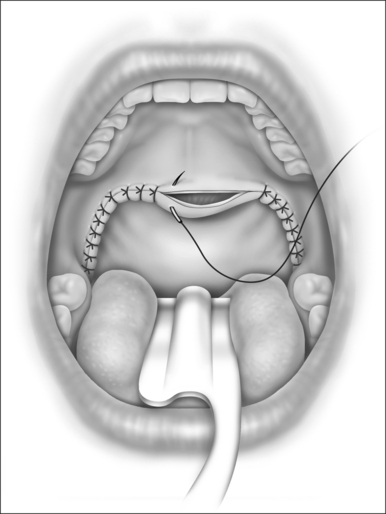

The soft palatal mucosa and submucosa (with glands and fat) are then stripped away from the muscular layers, beginning at the horizontal palatal incision and moving caudally toward the trailing edge of the soft palate and uvula. One or two brisk bleeders will often be encountered near the corners of the incision, and they must be suture-ligated with O plain catgut. (Cautery is inadequate and tissue-destructive, and it encourages stenosis.5) The uvula is amputated at the level of the trailing (caudal) edge of the soft palatal muscle fibers (Fig. 31.3). A tiny bleeder on each side of the uvula responds to a brief touch of electrocautery. Traction on the uvula during its amputation should be avoided because that results in excessive shortening of the uvula with interruption of the insertions of the levator palati muscles into the musculus uvulae. Loss of palatal sphincteric action (required for closure during speech and swallowing) has been attributed to excessive excision of the uvula and midline palatal tissue.

Tonsils (present in one-third of snoring and apnea patients) are excised, and other soft tissues between the posterior tonsillar pillars and the lateral incisions are all stripped out, down to the muscular layers. The plane of dissection is readily apparent when a tonsillectomy is performed. However, if a previous tonsillectomy was done, dense fibrous scar tissue will be encountered that will inhibit mobilization of the posterior pillars. This fibrous scar should be carefully stripped away from the underlying muscle fibers of the tonsillar fossa (superior pharyngeal constrictors); the dissection should avoid damage (and cautery) to the musculature so as to avoid penetration through the muscle into the underlying structures of the carotid sheath.5

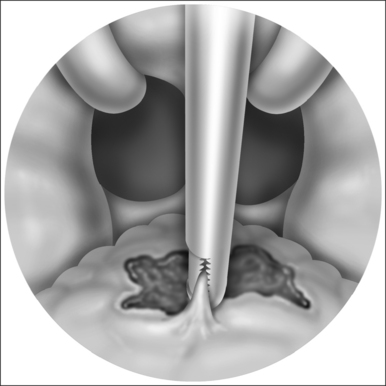

Bleeders are clamped and suture-ligated (which is less traumatic to the musculature and carotid sheath than is heavy electrocoagulation); good hemostasis is essential. Dissection below (caudal to) the lower pole of the tonsil is carried as far as visibility and safety allow, at which point lymphoid aggregations there and on the base of the tongue (lingual tonsils) may be reduced with gentle electrocoagulation.

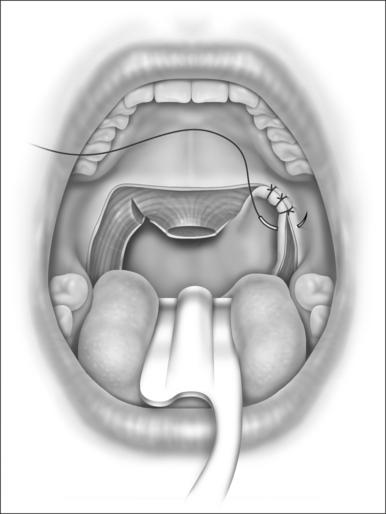

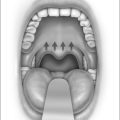

The posterior tonsillar pillar is then advanced in a lateral-cephalad direction toward the corner of the original palatopharyngeal incision (Fig. 31.4). Contiguous submucosal muscle fibers should be incorporated in this advancement because such a maneuver will increase the lateralizing effect and will expand the lateral dimension of the pharyngeal airway. This should also smooth and flatten out the redundancy and vertical folds of the posterior pharyngeal mucosa.3

Note that the best results are obtained from resection of the anterior pillar rather than the posterior pillar. This is because, when the intact posterior pillar is pulled forward (to cover the tonsillar fossa and to meet the incision of the resected anterior pillar), the soft palate will move along with it in a forward direction, thus enlarging the anterior posterior dimension of the nasopharynx. Conversely (and adversely), if the posterior pillar were to be resected, the closure would pull the anterior pillar and soft palate posteriorly, thus narrowing the nasopharynx.1

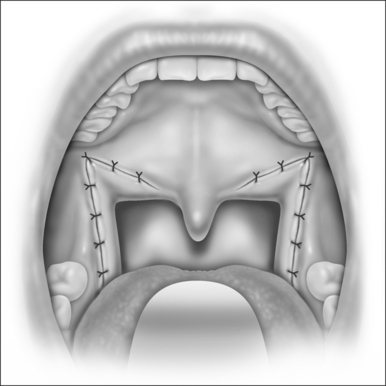

The pillar is advanced and fixated into its new, lateralized position with multiple sutures of 3–0 polyglycolic acid (Dexon-‘S’) or polyglactin 910 (Vicryl). The sutures should pass through the mucosa into superficial muscular layers so as to lateralize the muscular as well as the mucosal elements of the pillars (see Fig. 31.5). Furthermore, such closure eliminates ‘dead space’ where hematomas might accumulate. I prefer to put in the second stitch before I tie the first knot so that the positioning is more visible. Suturing then progresses downward (caudally) toward the tongue base, where a small opening is left unsutured to allow for spontaneous drainage.

The dissection and closure on the opposite side are identical (see Fig. 31.5).

Then the palatal closure is accomplished as the nasopharyngeal (posterior) surface of the soft palate mucosa is advanced over onto the oral (anterior) surface (Fig. 31.6). Redundant or flabby mucosa is trimmed, and the sutures are put into place, including a small amount of muscle fiber in the closure. Notice that the incisional/suture lines face forward (anteriorly), away from the nasopharynx and away from the caudal margin of the soft palate. This gives added protection against nasopharyngeal stenosis.

3 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

Any patient with significant obstructive sleep apnea before surgery will need vigilant postoperative monitoring of respirations. The intensive care unit is frequently the ideal place for the first 24 hours after surgery.6

Postoperative care for simple-snoring patients is the same as that for adult tonsillectomy patients. However, for obstructive sleep apnea patients, pain medication is given more cautiously (i.e. low-dose parenteral morphine or oral elixir of acetaminophen with added codeine, 30 mg/5 ml), with the recognition that apnea is aggravated by narcotics, and that life-threatening loss of airway can be precipitated, especially in the postanesthetic period or the period of postoperative edema of the airway.1,5,6

The criteria for discharge include a secure airway, adequate intake of fluids, and pain control with oral medications. The patient is sent home with instructions to avoid foods or drinks that are salty, scratchy, or sour. Liquid acetaminophen with codeine suffices for pain relief. Superficial wound contamination with oral microbial flora creates the equivalent of aphthous stomatitis at the surgical site. Recovery proceeds more rapidly if the patient uses the following ‘canker-sore’ mixture and procedure7:

4 RESULTS

Many – but not all – patients who undergo UPPP achieve remarkable relief of their snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness. Patient testimonials abound about lives having been dramatically changed. Furthermore, some studies suggest that the surgery, if successful, reduces to normal the exaggerated cardiovascular death rates seen in untreated obstructive sleep apneic patients.8

Acknowledgment

Figures 31.1–31.6 are reprinted from Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea, 3rd edn. Fairbanks DNF, Mickelson SA, Woodson BT, eds. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003, with permission.

1. Fairbanks DNF. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty techniques, pitfalls, and risk management. In: Fairbanks DNF, Mickelson SA, Woodson BT, editors. Snoring and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003:107-120.

2. Ikematsu T. Study of snoring, 4th report: therapy. J Jpn Otol Rhinol Larynogol. 1964;64:434-435.

3. Fujita S, Conway W, Zorick F, et al. Surgical corrections of anatomic abnormalities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923-934.

4. Dickson R, Blokmanis A. Treatment of obstructive sleep apnea by uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:1054-1058.

5. Fairbanks DNF. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty complications and avoidance strategies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;102:239-245.

6. Mickelson SA, Hakim I. Is postoperative intensive care monitoring necessary after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;119:352-356.

7. Fairbanks DNF. Pocket Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy in Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 12th edn. Alexandria, VA: American Academy of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery Fdn; 2005. p. 38

8. Lysdahl M, Haraldsson PO. Long-term survival after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in non-obese heavy snorers. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;119:352-356.