Chapter 60 Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: analysis of failure

1 INTRODUCTION

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) encompasses a spectrum of conditions including socially unacceptable snoring (SUS) and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Where SUS is mostly debilitating in social circumstances, OSAS and its complications pose a major health problem for society.1 Increased awareness has led to the development of various treatment modalities to combat both these diseases of which uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) is without doubt the most widely used surgical intervention.

UPPP was first performed in 1963 by Ikematsu,2 but modified and formally introduced as a surgical treatment for OSAS in 1981 by Fujita.3

2 PATIENT SELECTION

The next step in the work-up of suspected OSAS patients is a polysomnogram (PSG). This objective tool allows qualitative and quantitative measurements such as differentiation between SUS and OSAS and evaluation of the degree of disease severity. There are four levels of polysomnographic testing of which level I is the most elaborate, including recordings such as an electroencephalogram, registration of eye movements, submental electromyogram, registration of thoracic and abdominal respiratory movement, limb movements, oxygen saturation and the intensity of snoring all recorded in a clinical setting for the duration of at least 6 hours. The other levels are less extensive and not performed in a clinical setting.4 Events recorded during PSG and most commonly used to estimate severity and treatment outcome are the Apnea Index (AI), Apnea/Hypopnea Index (AHI), Respiratory Distress Index (RDI), Respiratory Arousal Index (RAI), Respiratory Effort Related Arousals (RERA) and Oxygen Desaturation Index (ODI). Recently the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) formulated recommendations for clinical and research definitions of PSG studies.5

A subjective measuring tool is the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), a questionnaire regarding hypersomnia. It was originally designed as an easy, non-invasive tool to distinguish SUS from OSAS.6 Although practical in use, it has been shown to have a low predictive value, and it cannot show the severity of the disease.

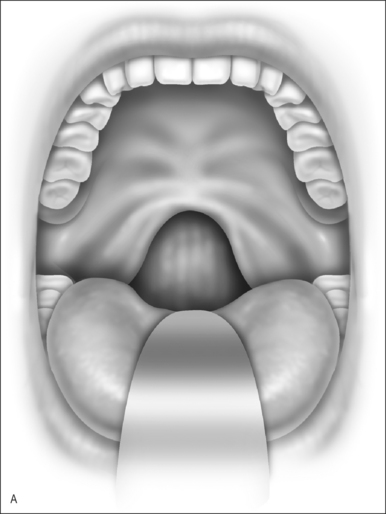

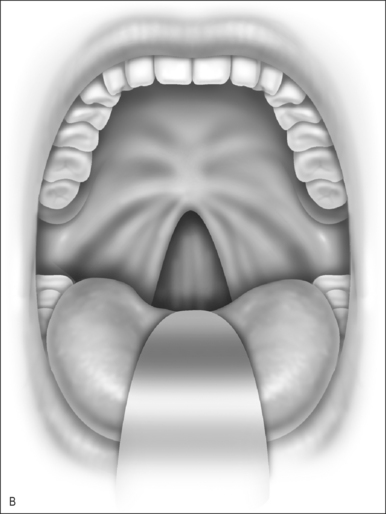

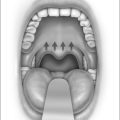

Mallampati et al. developed the Mallampati clinical scoring system in the mid-1980s to predict difficulty in tracheal intubation based on the ability to visualize the faucial pil-lars, soft palate and uvula base.7 The Mallampati score has been modified by Friedman et al. who then studied the value of this type of assessment in patients with obstructive sleep apnea.

Friedman modified the original Mallampati score in the following ways.

The Friedman staging system represents a clinical, anatomical staging system, independent of disease severity. Friedman et al. found patients classified with stage 1 disease had an 80.6% chance of successful cure with UPPP as opposed to success rates of respectively 38% and 8% in stage 2 and stage 3. The major advantage of this system is its easy use in various settings and its ability to predict which patients are most likely to fail (stage 3).8

Sleep(naso)endoscopy (sedated endoscopy) is another way of determining the levels of obstruction during induced sleep. This approach attempts to simulate the natural situation during snoring. Although this is a relatively time-consuming and costly method it is also the best option for topical preoperative dynamic diagnostic work-up for an ENT practice.9

Despite reports that each method is capable of good preoperative work-up, it is intriguing that the correlation between Friedman tongue position (or Friedman staging system) and findings with sleep endoscopy is low.10

The importance of determining the level of obstruction or collapsibility of the pharynx is increasingly recognized. Globally one way of describing the level of pharynx anatomy involves the subdivision into retropalatal and retrolingual obstruction. This has led to the following, much applied, preoperative classification: Type 1 refers to collapse at retropalatal level, Type 2 indicates collapse at both retropalatal and retrolingual level and Type 3 means collapse at the retrolingual area.11

4 POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

There are roughly three major groups of complications regarding UPPP.

In addition, there have been reports that tolerance to nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) was diminished after UPPP, which compounds treatment failure because other options are now less successful too.13

5 SUBJECTIVE AND OBJECTIVE TREATMENTOUTCOMES

A distinction should be made between subjective and objective treatment outcome. Although a reasonable correlation usually exists between objective and subjective outcome, unexplained discrepancies still occur in many circumstances. A clinical reality is that a rise in AHI or RDI can occur with subjective improvement and vice versa. One of the consequences is that repeated polysomnography should be performed in all OSAS patients after surgery. Unresolved ethical issues occur for instance in a happy (e.g. reduced snoring and/or improvement of hypersomnolence) patient after surgery who in repeated PSG is shown to have a rise in AHI or an unhappy patient with no subjective improvement but a distinctively lower AHI in repeated PSG recordings. Concerning these discrepancies between objective and subjective UPPP outcome, Lu et al. noted a long-term subjective improvement in 80% of their cases which was not correlated with the polysomnographic results.14 This raises the following question: if help-seeking behavior is mostly symptom driven and the patient now feels these symptoms no longer exist, how to motivate the patient for additional treatment to prevent long-term negative effect on health? The importance of treatment in (severe) OSAS is underlined by findings by Keenan et al. who showed that UPPP increases long-term survival in OSAS patients.15

5.1 OBJECTIVE DEFINITIONS OF OUTCOME

Success is most commonly objectively assessed by polysomnography. Over the past decades various cut-off points have been used in different studies estimating UPPP outcome of which a brief review follows. Fujita was the first to define the cut-off value for success as an AI reduction of 50%. Other variables taken into account included the level of oxygenation (SaO2>85%) and the number of arousals.3 The large meta-analysis of Sher et al. used an AI reduction with an absolute AI of 10 and/or an RDI reduction of 50%, with an RDI of less than 20 to evaluate treatment outcome.11 Larsson et al. also used an RDI reduction of 50% together with a reduced RDI of 20 or less for their long-term evaluation of UPPP outcome.16 A 50% reduction of the AHI was also used by Janson et al. and combined with an absolute AI value of 10 or less.17

Another frequently used outcome measure is the Oxygen Desaturation Index (ODI) where responders are defined as having a postoperative ODI of <20 with an ODI reduction of at least 50% compared to preoperative values.16,18

Issues that require attention in patient classification by PSG measurements are night-to-night variability and the influence of different types of leads when interpreting PSG values close to the cutoff point between responders and non-responders.5

For UPPP, another clinical distinction can be proposed:

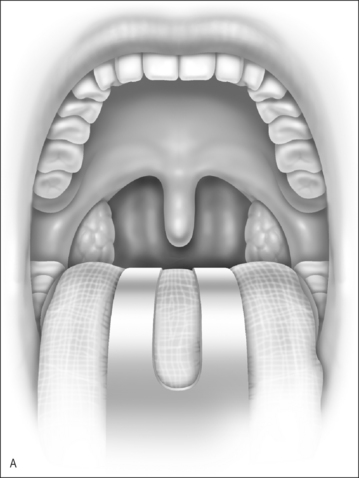

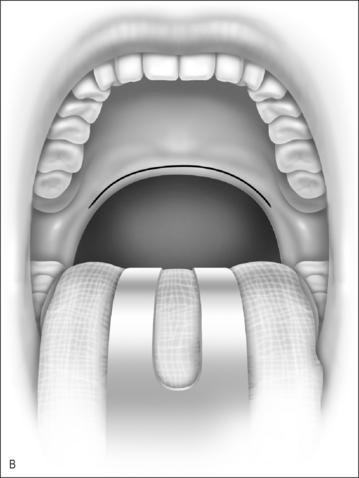

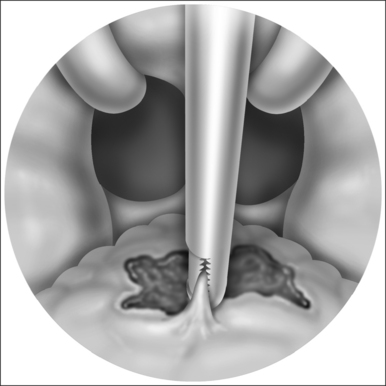

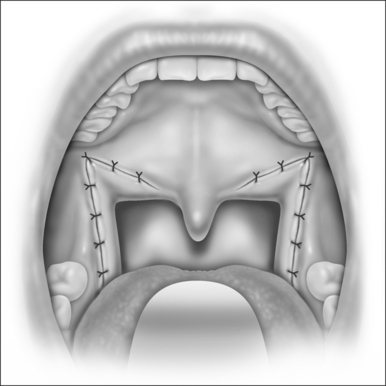

Nasopharyngeal stenosis is a much feared iatrogenic complication of UPPP. Severe stenosis is estimated to occur in less than 1% of post-UPPP cases.19 Based on the degree of severity, nasopharyngeal stenosis can be divided into mild/moderate stenosis (Figure 60.2A) or severe stenosis (Figure 60.2B), each requiring a different approach. Mild to moderate stenosis can be managed with Z-palatoplasty according to Friedman.20 In severe cases of NPS, Krespi and Kacker found that the use of CO2 laser combined with a custom-made nasopharyngeal obturator gives satisfactory long-term results in severe NPS management.19

6 DISCUSSION: ANALYSIS OF UPPP FAILURE

The most cited meta-analysis is definitely that of Sheret al.,11 showing an overall UPPP success rate of 40.7% in unselected patients. Sher et al. used as definition of success an AHI drop of >50% and AI <10. These data were early results in unselected patients, and since then it has become clear that level of obstruction determination is of paramount importance in improving success rates of any form of OSAS surgery. Better UPPP results can be expected in Type I patients (retropalatinal obstruction only), less good in Type 2 (both retropalatinal and retrolingual) and least satisfactory in Type 3 (retrolingual level only). Based on this rational approach definitive improvements of UPPP success percentages have been reported by, among others, Friedman et al.8 (using the Friedman staging system), and by Hessel and de Vries (after the use of sleep endoscopy) for patient selection.9

In the case of OSAS, Fujita et al. were the first to select the polysomnographic cut-off point of an AI drop of 50% to evaluate a group of UPPP patients.3 Fujita’s definition of success was used in the meta-analysis of Sher et al. and adjusted to include an AI <10 to provide more strict criteria.11 So far, this has been the most widely used way of attempting to evaluate UPPP outcome in an objective manner, although as discussed earlier many variations have been made and/or additional criteria added, leading to a confusing plethora of objective outcome measures. Hopefully the definitions recommended by the AASM in 2005 will lead to universal criteria and the formulation of uniform outcome measures to ease study comparison.5

6.1 UPPP FOR SOCIALLY UNACCEPTABLE SNORING

Simple snoring is often the result of soft palate vibration. UPPP targets this area and it is therefore no surprise that initial success rates in this situation are high at approximately 87%. Unfortunately this percentage is almost reduced to half after long-term follow-up.23A retrospective review of snoring surgery by Jones et al. cites a wide range in success rate of 45% (at 2 years) to even 90% (at 5 years) but the general trend is a regression of positive outcome with time. The estimated overall failure rate of snoring surgery (including UPPP and irrespective of type of surgery) is ∼66% at 2 years.24

Of equal importance is the level of partner satisfaction after UPPP. Prasad et al. found a significant reduction in sleep disturbance and an improved quality of life as measured by a questionnaire-based survey with a minimum of a 1-year follow-up.25

6.2 UPPP FOR OSAS

The range of success rates reported in various studies has a wide variation of 25–85%.26

In 1981 Fujita described the first cohort to be treated with UPPP and arbitrarily defined criteria for success which have since been widely applied. However, this value was based on the study group as a whole with large variation among the individuals. Even in this first study, two out of the total of 12 patients had an increase in apneas, although none indicated subjective worsening after UPPP. (Objective) UPPP ‘failure’ has been described from the beginning.3 Sher et al. did the first meta-analysis which showed a success rate of 50% when using the criteria defined by Fujita. This rate dropped to 40.7% in unselected patients when adjusted to include an AI of <10. The success rate was 52.3% in the group of patients clinically suspected of unilevel oropharyngeal obstruction, indicating the importance of anatomical staging.11

The first long-term follow-up (46 months) was by Larsson et al. in a group of 50 UPPP patients. Using a postoperative RDI <20 and a RDI reduction of at least 50% as the criteria for success, they found 60% of patients to be responders at 6 months. This amount decreased to 38.8% by 21 months but climbed back to 50% at a mean of 46 months.16 Janson et al. found a positive response of 64% 6 months postoperatively but a similar percentageof responders (48%) to other studies after a 4 to 8-yearfollow-up using a 50% or more decrease in AHI and a postoperative AI of less than 10 as criteria for success.17 In 2000 Boot et al. published results of another long-term follow-up in unselected patients. Using ODI as criterion for success,this study showed that only ∼20% remained as responderover time.18

Senior et al. found UPPP to be effective in 40% of their cohort of mild OSAS patients. Their study supported the increasing evidence of sub-optimal UPPP treatment outcome. However, the non-responders showed objective worsening on polysomnographic evaluation combined with lack of subjective symptom improvement.21 This finding drew attention to an underreported aspect of UPPP outcome in the literature. Deterioration after UPPP was also noted by Hessel and de Vries who even found some failures in the Type 1 and 2 groups despite preoperative selection by sleep endoscopy. They reported better than average results of UPPP with use of sedated endoscopy for patient selection but encountered failures (deterioration) in approximately 10–15%. Results were negatively influenced by previous tonsillectomy (with relative short anterior–posterior diameter at retropalatinal level) and simultaneous obstruction at tongue base level (Type 2 does worse than Type 1).22

6.3 COMPLICATIONS

Another aspect of UPPP failure is the occurrence of complications. Grontved and Karup administered a questionnaire to 69 patients 2 years post-UPPP. They found that 42% had complaints.27Although the majority of these were minor, it shows that patient satisfaction deserves ample attention and underlines the importance of both objective and subjective rating of surgical success.

This aspect was studied by Walker-Engstrom and colleagues who assessed quality of life after treatment of mild to moderate OSAS patients with either a dental appliance or UPPP over a 1-year follow-up period. They found that although both interventions led to significant improvement in quality of life (evaluated by the dimensions vitality, contentment and sleep), the subjective improvement was greater for UPPP. However, the AI and AHI rate (<5 resp. <10) was more normalized in the dental appliance group than the UPPP group (78% vs. 51%), underlining once again the frequent discrepancy between subjective and objective treatment outcomes.28

It is concerning to discover that long-term outcome of UPPP on OSAS shows a high level of relapse.17,18,21 Furthermore, there are increasing reports of disease deterioration after surgical intervention.21,22 This raises the question whether it is justified to put patients at risk of surgery for an intervention that in the long run is likely to give minimal to no improvement and possibly even worsening of the situation. UPPP indeed appears not to be the single-step answer but it does prove sufficient therapy for a specific group of patients. The subsequent question therefore is: which patients are these and how do we identify them preoperatively?

6.4 WHICH FACTORS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH THE VARYING RESPONSE RATE TO UPPP?

Multilevel involvement is probably one of the most complicating factors in OSAS management. UPPP targets the oropharyngeal level but collapse at the hypopharyngeal level, if present, is not altered.21,26

The influence of preoperative weight or Body Mass Index is a much debated issue. Riley et al. found that morbidly obese patients had less successful UPPP outcome.29 However, there are conflicting results, as Sher et al. found no significant effect of BMI on UPPP outcome in their large meta-analysis.11 On the other hand, Larsson et al.6 found a significant lower preoperative BMI in their responder group but this was not confirmed by Boot et al.30 Larsson et al. also found a negative influence of postoperative weight gain on UPPP efficacy which was partly reversed in the same group after weight reduction.16

As for the severity of the disease, Sher et al. found that UPPP is less successful in more severe cases of OSAS and this relationship remained apparent despite stricter adjustment of the definition of success.11 Using the same criteria for success, Senior et al. found no difference in UPPP outcome between mild and severe OSAS patients.21 This finding was also supported by Friedman et al. who showed that their clinical anatomical staging system is superior to disease severity in predicting UPPP outcome.26

The influence of gender is interesting, foremost because of the significant difference in the pattern of SDB between the sexes, such as presenting symptoms, the severity of disease and the association with BMI. This is an area that needs further research, as does the role of ethnicity, which shows differences in the distribution of risk factors among various ethnic groups without a clear explanation. Age shows a tendency to increase the prevalence of snoring and OSAS up until middle age after which there is no further change.1 Once again the exact mechanism is unknown.

Other comorbidities such as disproportionate anatomy, allergy and hypoventilation syndrome have been observed but their precise contribution as potential risk factors is less studied.1

Polysomnographic recordings are the most frequently used way of obtaining objective data on pre- and postoperativeoutcome. An aspect that until recently was not fully recognized and included in these recordings is the so-called ‘positional sleep apnea’. These so-called position-dependent OSAS patients have an AHI in a supine position that is twice the AHI in other positions. Awareness of this positional sleep apnea phenomenon and correction for it, if necessary, when interpreting polysomnographic results can influence overall UPPP outcome.31,32

6.5 THE VALUE OF PREOPERATIVE PATIENT SELECTION FOR UPPP

To date, polysomnography remains the backbone of the OSAS diagnostic work-up for disease severity and the most frequently used way of selecting patients for surgery and evaluating postoperative outcome. Although poly-somnography is a valuable instrument in obtaining objective data it does not give information on the levels involved in upper airway collapse. Topical diagnostic work-up is presently either done by clinical examination only (e.g. using the Mallampati–Friedman staging) or (in combination) with sleep endoscopy. Sleep endoscopy is in our own experience the most feasible and promising technique to address this issue, but the subject is highly controversial in whether all patients in whom surgery is considered should have sleep endoscopy routinely performed. Hessel and de Vries showed that UPPP success rate (defined as an AHI drop <20) almost doubles by preoperatively combining PSG and sleep endoscopy in the diagnostic work-up.9 This study revealed two interesting findings. The first and only statistically significant finding is that UPPP is less successful in patients with prior tonsillectomy as many of these patients have a relatively shorter anterior–posterior diameter between posterior pharyngeal wall and soft palate. This has led to an important change in our policy. Currently we more frequently perform ZPP than simple UPPP in these cases.

The other important finding in this study confirmed that cases of combined retropalatal–retrolingual obstruction did worse than sole palatal obstruction. Therefore we now manage Type 2 cases with a relatively low AHI by combined UPPP and radiofrequency of the tongue base, while in more severe obstruction (as assessed by sleep endoscopy and higher AHI) we prefer to combine UPPP, radiofrequency of the tongue base and hyoid suspension as primary surgery, instead of UPPP only (see Chapter 50: Multilevel surgery). Continuing on our experience with multilevel surgery, we found that secondary hyoid suspension after UPPP failure is less successful than primary hyoid suspension for patients with obstruction at tongue base level and moderate to severe OSAS (see Chapter 49: Hyoid suspension as the only procedure). In addition, a respectively relative or functional post-UPPP stenosis at palatal level can often not be salvaged by hyoid suspension.33

Once again we emphasize the importance of careful preoperative assessment. Our preference remains the combination of PSG and sleep endoscopy despite understandable criticism over sleep endoscopy (the primary question being: is artificially induced sleep a reliable representation of natural sleep?). We feel that at present there are no better methods to preoperatively (dynamically) diagnose the level of obstruction in OSAS especially as recent investigation of the correlation of the Mallampati/Friedman staging system with sleep endoscopy showed a low correlation.10

In general, when attempting to evaluate UPPP outcome (and failure) the ongoing difficulty with the available literature is the lack of uniform definitions of success and the use of modified UPPP techniques with adjunctive measures, which makes comparison difficult and inconclusive and at times yields conflicting results.34

1. Boehlecke BA. Epidemiology and pathogenesis of sleep-disordered breathing. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2000;6:471-478.

2. Ikematsu T. Study of snoring 4th report Therapy [in Japanese]. J Jpn Otol Rhinol Laryngol Soc. 1964;64:434-435.

3. Fuijta S, Conway W, Zorick F, Roth T. Surgical correction of anatomic abnormalities in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1981;89:923-934.

4. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Practice parameters for the indications of polysomnography and related procedures. Sleep. 1997;20:406-422.

5. Kushida CA, Littner MR, Morgenthaler T, et al. Practice parameters for the indications for polysomnography and related procedures: an update for 2005. Sleep. 2005;28:499-521.

6. Johns MA. new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540-545.

7. Mallampati SR, Gatt SP, Gugino LD, et al. A clinical sign to predict difficult tracheal intubation: a prospective study. Can Anaesth Soc J. 1985;32:429-434.

8. Friedman M, Ibrahim H, Lee G. Clinical staging for sleep-disordered breathing: a guide to surgical treatment. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;13:191-195.

9. Hessel NS, de Vries N. Results of UPPP after diagnostic work-up with PSG and sleep endoscopy; a report of 136 snoring patients. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:91-95.

10. den Herder C, van Tinteren H, de Vries N. Sleep endoscopy versus modified Mallampati score in sleep apnea and snoring. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:735-739.

11. Sher AE, Schechtman KB, Piccirillo JF. The efficacy of surgical modifications of the upper airway in adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1996;19:156-177.

12. Kezirian EJ, Weaver EM, Yueh B, et al. Incidence of serious complications after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:450-453.

13. Mortimore IL, Bradley PA, Murray JAM, Douglas NJ. Uvulopalatoplasty may compromise nasal CPAP therapy in sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1759-1762.

14. Lu SJ, Chang SY, Shiao GM. Comparison between short-term and long-term postoperative evaluation of sleep apnoea after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:308-312.

15. Keenan SP, Burt H, Ryan CF, Fleetham JA. Long-term survival of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated by uvulopalatopharyngoplasty or nasal CPAP. Chest. 1994;105:155-159.

16. Larsson LH, Carlsson Nordlander B, Svanborg E. Four year follow-up after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in 50 unselected patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1994;104:1362-1368.

17. Janson C, Gislason T, Bengtsson H, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome treated with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;23:257-262.

18. Boot H, Wegen van R, Poublon RML, et al. Long-term results of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:469-475.

19. Krespi YP, Kacker A. Management of nasopharyngeal stenosis after uvulopalatoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:692-695.

20. Friedman M, Ibrahim HZ, Vidyasagar R, et al. Z-palatoplasty (ZPP): a technique for patients without tonsils. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131:89-100.

21. Senior BA, Rosenthal L, Lumley A, et al. Efficacy of uvulopalatopharyngoplasty in unselected patients with mild obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:179-182.

22. Hessel NS, de Vries N. Increase of apnoea–hypopnoea index after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty: analysis of failure. Clin Otolaryngol. 2004;29:682-685.

23. Hicklin LA, Tostevin P, Dasan S. Retrospective survey of long-term results and patient satisfaction with uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for snoring. J Laryngol Otol. 2000;114:675-681.

24. Jones TM, Earis JE, Calverley MA, Swift AC. Snoring surgery: a retrospective review. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2010-2015.

25. Prasad KR, Premraj K, Kent SE, Reddy KTV. Surgery for snoring: are partners satisfied in the long run? Clin Otolaryngol Alli Sci. 2003;28:497-502.

26. Friedman M, Vidyasagar R, Bliznikas D, Joseph N. Does severity of obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome predict uvulopalatopharyngoplasty outcome? Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2109-2113.

27. Grontved Am, Karup P. Complaints and satisfaction after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl.. 2000;543:190-192.

28. Walker-Engstrom ML, Wilhelmsson B, Tegelberg A, et al. Quality of life assessment of treatment with dental appliance or UPPP in patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnoea. A prospective randomized 1-year follow-up study. J Sleep Res. 2000;9:303-308.

29. Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a review of 306 consecutively treated surgical patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:117-125.

30. Boot H, Poublon ML, van Wegen R, et al. Uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome: value of polysomnography, Mueller manoeuvre and cephalometry in predicting surgical outcome. Clin Otolaryngol. 1997;22:504-510.

31. Oksenberg A, Silverberg D, Arons E, Radwan H. Positional vs. non positional obstructive sleep apnea patients: anthropomorphic, nocturnal polysomnographic and multiple sleep latency test data. Chest. 1997;112:629-639.

32. Richard W, Kox D, Herder den C, et al. The role of sleep position in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006. EPub ahead of print

33. Den Herder C, van Tinteren H, de Vries N. Hyoidthyroidpexia: a surgical treatment for sleep apnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:740-745.

34. Schechtman MB, Sher AE, Piccirillo JF. Methodological and statistical problems in sleep apnea research: the literature on uvulopalatopharyngoplasty. Sleep. 1995;18:659-666.