Synonyms/Description

Intrauterine adhesions or synechiae

Etiology

Most cases of intrauterine adhesions result from trauma to the endometrium, primarily from dilation and curettage (D&C) procedures. Patients most at risk for developing Asherman’s syndrome are those undergoing D&C postpartum for retained products of conception, incomplete spontaneous abortion (SAB), or therapeutic abortion (TAB). Intrauterine synechiae can occur after any procedure or process that causes trauma to the normal endometrium. Examples in addition to those discussed include abdominal or hysteroscopic myomectomy, hysteroscopic septoplasty, and previous placenta accreta, among others. Synechiae are connective tissue bands that disrupt the endometrium, causing a lack of distention of the uterine cavity. They are associated with recurrent pregnancy loss and infertility.

Schenker and Margalioth studied 1856 cases of Asherman’s syndrome and showed that pregnancy was the main predisposing factor in 90.8% of the patients, with 66.7% of cases occurring after D&C for SAB or TAB, 21.5% after postpartum D&C, 2% after Cesarean section, and 0.6% after evacuation of trophoblastic disease.

These results appear to show that the endometrium is most vulnerable to developing Asherman’s syndrome during the hypoestrogenic state immediately after pregnancy.

Asherman’s syndrome may also occur after endometrial ablation. These procedures aim to destroy the basalis layer of the endometrium to decrease menstrual bleeding. If synechiae occur, it makes subsequent evaluation of any abnormal bleeding extremely difficult.

Ultrasound Findings

In patients with Asherman’s syndrome, the endometrial echo is difficult to see, with irregular borders and disruptions of the endometrial lining in multiple areas. There may also be small, focal, cystic-like areas containing blood within the endometrial cavity, trapped by the adhesions. Using 3-D ultrasound, the outline of the endometrial cavity is irregular, shaggy, and distorted. Linear adhesions are usually seen, traversing the endometrium, leaving small islands of endometrial echo.

The most accurate method for diagnosing Asherman’s syndrome is sonohysterography, in which saline is injected into the uterine cavity through a small catheter threaded through the cervix. In severe cases, it may not be possible to distend the cavity at all, thus confirming the diagnosis of extensive adhesions. The adhesions may be seen sonographically traversing the cavity in patients when saline can distend the cavity even slightly.

Differential Diagnosis

The clinical history is essential in making the diagnosis of Asherman’s syndrome. A likely scenario is a patient presenting with infertility and amenorrhea whose history is significant for a D&C following her last pregnancy.

The ill-defined endometrial echo may suggest the diagnosis of adenomyosis, although in that case the uterus is typically globular and asymmetric, which is not usually a feature of Asherman’s syndrome. Fibroids or polyps can also distort the endometrium, but these patients typically complain of excess bleeding, unlike patients with intrauterine adhesions, who are more likely to present with amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea.

It is remotely possible that a thick synechia could be confused with a uterine septum, although

it is unlikely because of the asymmetry of adhesions compared with septa.

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Patients with significant Asherman’s syndrome are usually infertile and amenorrheic. They are typically treated with hysteroscopic lysis of adhesions, sometimes with intrauterine “stenting,” followed by treatment with sequential estrogen and progesterone therapy to repair the endometrium.

Figures

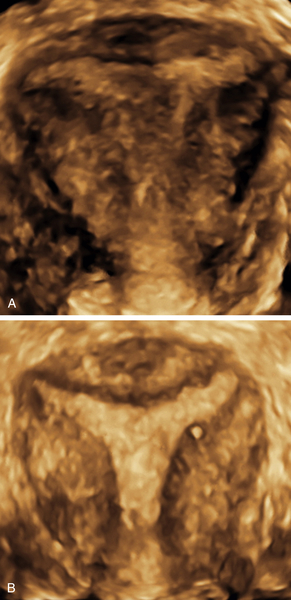

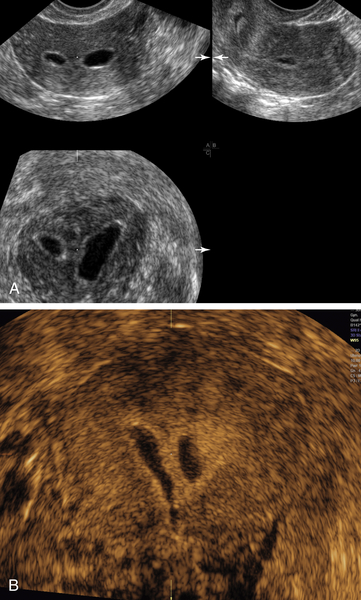

Figure S1-1 A and B, Two 3-D coronal views of a patient with Asherman’s syndrome. Note the echolucent linear jagged structures (adhesions; arrows) traversing the endometrial cavity.

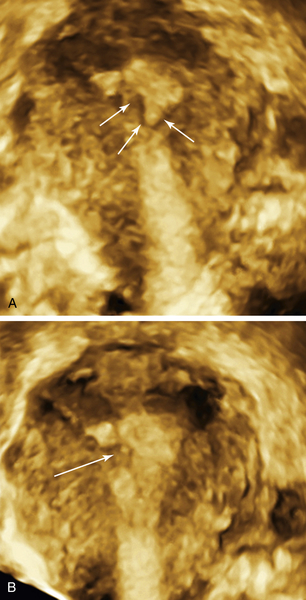

Figure S1-2 A and B, 2-D and 3-D views of a severely scarred (arrows) endometrium in a patient who had recurrent SABs and D&C’s.

Figure S1-3 A, 3-D coronal view of the shaggy endometrial cavity in a patient with Asherman’s syndrome and infertility. B is a similar view of the same uterus after hysteroscopic surgery for lysis of the adhesions. Note that the margins of the endometrium are sharper and smoother than preoperatively.

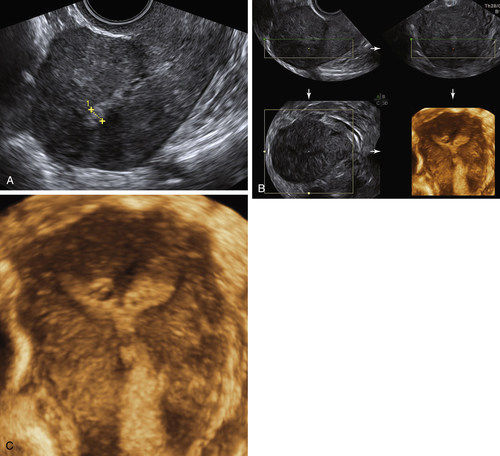

Figure S1-4 A to C, 2-D, multiplanar, and 3-D rendering of the uterine cavity in a patient who had an endometrial ablation because of excessive vaginal bleeding. Note the irregular outline and severe scarring of the margins of the cavity; this should not be confused with a partial septum.

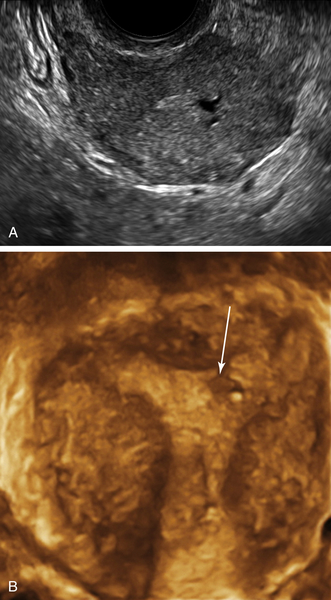

Figure S1-5 A and B, Two different patients with uterine synechiae seen during a sonohysterogram. Note the fluid outlining the adhesion within the uterine cavity. These adhesions are similar in appearance to a uterine septum, although correctly diagnosed because of asymmetry.